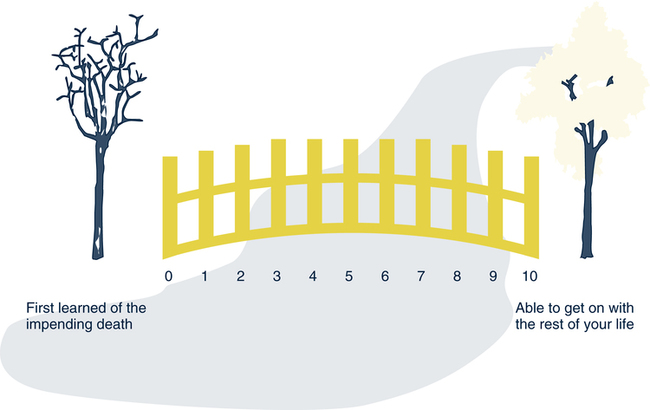

Patricia M. Burbank, DNSc, RN and Jean R. Miller, PhD, RN On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Distinguish among loss, bereavement, grief, and mourning. 2. Discuss factors that may affect the length of time of bereavement. 3. Identify physical, psychologic, social, and spiritual aspects of normal grief responses. 4. Describe four ways that complicated grief reactions may manifest themselves. 5. Discuss the tasks of mourning. 6. Describe nursing care activities for assisting bereaved older adults. 7. Discuss physical, psychologic, social, and spiritual aspects of dying for older adults. 8. Explain age-related changes that affect older adults who are dying. 9. Describe nursing strategies for assisting dying older adults and their families. The terms loss, bereavement, grief, and mourning are often used interchangeably, but these words convey different meanings (Corr & Corr, 2007). Loss is a broad term that connotes losing or being deprived of something such as one’s health, home, or a relationship. Bereavement is the state or situation of having experienced a death-related loss. Grief is one’s psychologic (cognitive or affective), physical, behavioral, social, and spiritual reactions to loss. Mourning is often used to refer to the ritualistic behaviors in which people engage during bereavement. More recently, mourning is the term used for processes related to learning how to live with one’s loss and grief. Many older adults experience multiple losses with little time for grieving between the losses. The emotional crises imposed by these multiple losses can lead to disorientation, mental confusion, and withdrawal. Individual coping styles, the existence of support systems, the ability to maintain some sense of control, and the griever’s health status and spiritual beliefs all influence a person’s responses to multiple losses (Garrett, 1987). As already mentioned, bereavement involves a death-related loss. The time that one spends in the period of bereavement is affected by many factors. The death of one’s spouse or life partner is usually the most significant loss that an older person may experience. It involves the loss of a companion who often is one’s best friend, sexual partner, and partner in decision making and household management, as well as a contributing source to one’s definition of self or identity. Because many older couples frequently divide the tasks of daily living, surviving spouses must take on new responsibilities while coping with the loss of their loved ones. Perceived social support after the death of a spouse has been shown to be a factor affecting the adjustment of many surviving spouses (Balk, 2007). Other factors that can affect bereavement outcomes include ambivalent or dependent relationships, mental illness, low self-esteem, and multiple prior bereavements (Sheldon, 1998). Although bereavement after the death of a spouse is a highly stressful process, Lund’s (1989) summary of studies of widowed persons concluded that many older surviving spouses are resilient. While 72% of those studied reported that the spouse’s death was the most stressful event they had ever experienced, they also reported high coping abilities. The overall effects of grief on the physical and mental health of many older adults were not as severe as expected, and both positive and negative feelings were experienced simultaneously. Loneliness and problems associated with tasks of daily living were two of the most common difficulties reported. Although bereaved older adults adjusted in many different ways to the deaths of their spouses, in general the most difficult period occurred in the first several months, improving gradually but unsteadily over time. Lund’s (1989) review also showed that older men and older women are more similar than dissimilar in their bereavement experiences and adjustment. Age, income, education, and anticipation or forewarning of death did not seem to have much effect on future adjustment processes. Religion-related variables also did not contribute much to adjustment. Social support was moderately helpful in the adjustment process, as were internal types of coping resources such as independence, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and competency in performing tasks of daily living. Older adults’ normal grief responses to the loss of a spouse were summarized by Lund (1989). The following conclusions, drawn from his work, speak specifically to the bereavement experiences of older persons: • Bereavement adjustments are multidimensional in that nearly every aspect of a person’s life can be affected by the loss. • Bereavement is a highly stressful process, but many older surviving spouses are resilient. • The overall effect of bereavement on the physical and mental health of many older spouses is not as devastating as expected. • Older bereaved spouses commonly experience both positive and negative feelings simultaneously. • Loneliness and problems associated with the tasks of daily living are two of the most common and difficult adjustments for older bereaved spouses. • Spousal bereavement in later life might best be described as a process that is most difficult in the first several months but that improves gradually, if unsteadily, over time. The improvement may continue for many years, but for some it may never end. • There is a great deal of diversity in how older bereaved adults adjust to the death of a spouse. Normal grief reactions can be characterized by time: early, middle, and last phases. In the early phase, shock, disbelief, and denial are common. This phase commonly ends as people begin to accept the reality of the loss after the funeral. The middle phase is a time of intense emotional pain and separation and may be accompanied by physical symptoms and labile emotions. Lastly, reintegration and relief occur as the pain gradually subsides and a degree of physical and mental balance returns (DeSpelder & Strickland, 1992). Studies of grief responses have consistently identified common psychologic responses. Feelings of sadness are the emotions most often mentioned (Worden, 1991). Other common feelings include guilt, anxiety, anger, depression, apathy, helplessness, and loneliness. Guilt and regret regarding one’s relationship with the person who has died can be especially troublesome (Landman, 1993). Shock and disbelief may immediately follow the death or loss. The bereaved person may also display diminished self-concern, a preoccupation with the deceased, and a yearning for his or her presence. Some older persons become confused and unable to concentrate after the death of someone significant to them. Grief spasms, periods of acute grief, may come when least expected (Rando, 1988). How the grief response manifests itself is individually determined by sociocultural factors in addition to the quality of the relationship between the deceased and the mourner. For some older persons the grief experience may include feelings of relief and emancipation, especially after prolonged suffering or a difficult relationship. Religion and spirituality can provide a stabilizing influence during grief. One’s religious institution may provide the sense of belonging to a group of people who support one another in times of need. Some may experience a deep inner sense of peace that they are being cared for by a higher power. For others, however, the grief experience may precipitate a crisis in their beliefs and values. Gender, social class, ethnicity, and culture may influence one’s spiritual response to grief (Doka & Davidson, 1998) (see Cultural Awareness Box). approach that separates the mind, body, and spirit is not advocated. One’s responses to loss and death are characterized by (1) changes over time, (2) one’s natural reaction to all kinds of losses, not just death, and (3) one’s unique perception of the loss (Rando, 1988). Anticipatory grief is defined as grieving that occurs before the actual loss. It includes the processes of mourning, coping, and planning that are initiated when the impending loss of a loved one becomes apparent (Rando, 1986). These can be healthy responses to an impending death, but they also can have a negative impact on the relationship with the dying person when one’s energies are predominantly focused on the future. Anticipatory grief may account for some persons’ apparent lack of overt grief reactions after the death of a loved one who experienced a long terminal illness. Anticipatory grief increases as death becomes imminent and ends when the death occurs. Anticipatory grief helps reduce early shock, confusion, and depression. Survivors who resolve grief before the death of a loved one may be criticized by others or experience self-reproach for lack of a grief reaction to the actual death. These responses can lead to further problems of adjustment. Disenfranchised grief is grief that is not or cannot be openly acknowledged (Doka, 1989). This complicates the grieving process both because it cannot be expressed and because social support is not available. Doka (1997, 2002) described four major situations that cause disenfranchised grief: (1) when a relationship is not recognized by others (e.g., cohabitation, same-sex partners), (2) when a loss is not acknowledged (e.g., death of a pet), (3) when the griever is excluded (e.g., very old adults, those with cognitive deficits), and (4) when the circumstances of the death are disenfranchising (e.g., deaths caused by drunk driving or suicide). Complicated grief reactions may manifest as one of four types: (1) chronic, (2) delayed, (3) exaggerated, or (4) masked. Chronic grief reactions are prolonged and never reach a satisfactory conclusion. Because bereaved individuals are aware of their continuing grief, this reaction is fairly easy to recognize. A therapist can assess which tasks of grieving are not being resolved and why. The goal of intervention is to resolve these tasks (Worden, 1991). Exaggerated grief reactions occur when normal feelings of anxiety, depression, or hopelessness grow to unmanageable proportions. People with exaggerated grief may feel an overwhelming sense of being unable to live without the deceased person. They may lose the sense that the acute grief is transient and may continue in this intense despair for a long time (Worden, 1991). Masked grief reactions occur when bereaved persons experience feelings related to the loss but cannot express or recognize the source of these feelings. This reaction may occur as a self-protective mechanism because some people may not be able to bear the stress of mourning. Repression of grief responses usually manifests as either a physical symptom, often similar to one that the deceased experienced, or as some type of maladaptive behavior (Worden, 1991). In summary, Rando (1988) outlined factors that influence how people experience and express their grief. Categories of psychologic factors include the characteristics and meaning of the lost relationship, the personal characteristics of the bereaved, and the specific circumstances surrounding the death (Table 20–1). Social factors include the griever’s support system, sociocultural and religious background, education and economic status, and funerary rituals. An individual’s physical state also influences the grief response. Important physical factors are the use of drugs and sedatives, nutritional state, adequacy of rest and sleep, exercise, and general physical health. Nurses need to be aware of how all these factors affect dying persons and their families so that they may provide the best care possible. TABLE 20–1 PSYCHOLOGIC FACTORS INFLUENCING GRIEF RESPONSES Modified from Rando TA, editor: Loss and anticipatory grief, Lexington, Mass, 1986, Lexington Books. Used with permission of Therese A. Rando, PhD. Mourning was defined at the beginning of this chapter in two ways: (1) ritualistic activities such as wearing dark clothes during bereavement or lighting candles for the dead and (2) processes related to learning how to live with one’s loss and grief. Each way is prescribed by social and cultural norms that indicate acceptable coping behaviors in a person’s society (Doka & Davidson, 1998). The emphasis in this section will be on the processes of learning to live with loss of a loved one and will include the traditional stage/phase perspectives of adjustment, tasks of mourning, and two meaning-making approaches. The complexity of the mourning process does not lend itself to a single theory. Most of the stage/phase theories of mourning have some aspect of the following concepts: avoidance, assimilation, and accommodation (Neimeyer, 2000). Avoidance is often felt when one is first confronted with the death of a loved one. The news is hard to believe; however when the reality is viewed as a fact, strong emotions can emerge. Deep emotional pain and even anger toward those seen as responsible for the death, such as doctors, the deceased person, or God, is common. Gradually the reality of the new situation without the loved one is assimilated. This can be a time of despair when the void left by the deceased is felt deeply. Eventually the physical, behavioral, psychologic (cognitive or affective), social, and spiritual reactions to the loss decrease, and the bereaved move into the accommodation stage/phase. This is a time when the bereaved begin to accept the loss, move on in their lives, and yet remain attached to their loved ones in a healthy way. An example of a stage/phase approach to mourning is Lindemann’s (1944) early study of survivors of the 1942 Coconut Grove fire in Boston in which he identified physical and psychologic symptoms associated with acute grief. The ages of the mourners were not known. Worden’s (1991, 2002) tasks of mourning are a more active and useful way to think of mourning among older persons. He described the following four tasks of mourning: (1) accept the reality of the loss, (2) experience or work through the pain of grief, (3) adjust to an environment in which the deceased is missing, and (4) emotionally relocate the deceased and move on with life. The first task, accepting the reality of the loss, involves coming to the realization that the person is dead, that he or she will not return, and that reunion, at least in life as we know it, is impossible. The second task, experiencing the pain of grief, is necessary to prevent the pain from manifesting itself in some other symptom or problematic behavior. Sociocultural customs that discourage open expression of grief often contribute to unresolved grief. The third task, adjusting to an environment in which the deceased is missing, involves developing new skills and assuming the roles for which the deceased was responsible. The last task, the withdrawal of emotional energy and the reinvestment in another relationship, entails withdrawing emotional attachment to the lost person and loving another living person in a similar way. For many, this last task is the most difficult. The final task, emotionally relocating the deceased and moving on with life, gives the bereaved person permission to invest emotionally in others without being disloyal to the lost loved one. Although Worden (1991) pointed out that in one sense mourning is never over, he also stated that in losses that involve a great deal of emotional attachment, the process takes at least 1 year before the wrenching pain subsides. Some older spouses have reported that they feel as though they will never “get over” their loss; instead, they have learned to live with it (Lund, 1989). Burbank (1992) found that the major source of meaning in life among older persons came from relationships with family members. When loved ones die, meaning derived from these relationships changes. Personal beliefs and attitudes, including cultural and religious ones, influence how the meanings of the losses are perceived. Some of the more common perceptions attached to illness and death are punishment by a supreme being, suffering that must be overcome or endured, a normal part of the life experience, and an opportunity for personal growth and transcendence. The meaning of a loss to a bereaved person has a significant effect on his or her responses to that loss. For this reason, it is important that caregivers explore the perceptions of the bereaved to understand and assist them as they mourn their loss. Neimeyer (2000) proposed that reconstructing the meaning in a person’s life after the death of a loved one is an important process of mourning. The bereaved are encouraged to find or create new meaning in their lives and in the deaths of the deceased. This is a cognitive process that is affected by one’s social context as well as one’s individual resources. The multiple definitions of meaning, however, require further clarification. Holland, Currier, and Neimeyer (2006) found that the words, “sense-making” and “benefit-finding,” were central to finding meaning. Their research indicated that better outcomes came from making sense of the death and the resulting life of the survivor than from finding benefits from the death such as reordering life priorities and becoming more empathetic. The dual process model of coping with bereavement is another way to make meaning after the death of a loved one. In this model Stroebe and Schut (2001) suggested that the bereaved waver between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented approaches to everyday life experiences. Regardless of whether persons are in loss-oriented or restoration-oriented states, they vacillate between positive and negative meaning (re)construction until, over time, they become more focused on positive meaning reconstruction. For instance, persons might vacillate between positive reappraisal of the situation and negative rumination about the death, but they gradually spend more time making meaning from positive reappraisals of their situation. A simple tool to assess progress in bereavement is the 10-Mile Mourning Bridge (Huber & Gibson, 1990) (Fig. 20–1). This tool, useful for both clinical assessment and research purposes, draws on Worden’s (1991) work and is conceptualized as a journey across a 10-mile bridge. On the bridge, the 0 represents the time before grief. The 10 reflects Worden’s last stage, where clients recover the emotional energy consumed by grieving and reinvest it in their own lives. It is not suggested that people ever “get over” the death of a loved one but rather that grief can cease to be the primary focus of life. Clients can use the 10-Mile Mourning Bridge as a self-assessment tool with daily or weekly frequency, as determined by the client. Because each person’s grief experience is unique, the miles on the bridge are only defined at each end. The use of this instrument can also facilitate client–nurse discussions about grief and progress (Huber & Bryant, 1996).

Loss and End-of-Life Issues

Definitions

Losses

Bereavement

Grief

Psychologic Responses

Spiritual Aspects

Types of Grief

CHARACTERISTICS AND MEANING OF LOST RELATIONSHIP

PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS OF BEREAVED

SPECIFIC CIRCUMSTANCES OF DEATH

Nature and meaning of loss

Coping behaviors, personality, and mental health

Immediate circumstances of death

Qualities of lost relationship

Timeliness of death

Role and function filled by deceased

Level of maturity and intelligence

Perception of preventability

Characteristics of deceased

Past experiences with loss and death

Sudden versus expected death

Amount of unfinished business between bereaved and loved one

Social, cultural, ethnic, and religious background

Length of illness before death

Anticipatory grief and involvement

Perception of deceased’s fulfillment in life

Sex-role conditioning

Number, type, and quality of secondary losses that accompany the death

Presence of concurrent stress or crises in life

Mourning

Stage/Phase Perspectives

Tasks of Mourning

Meaning Making

Nursing Care

Assessment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Loss and End-of-Life Issues

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access