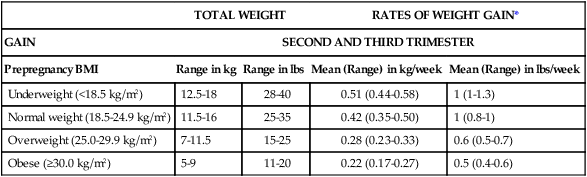

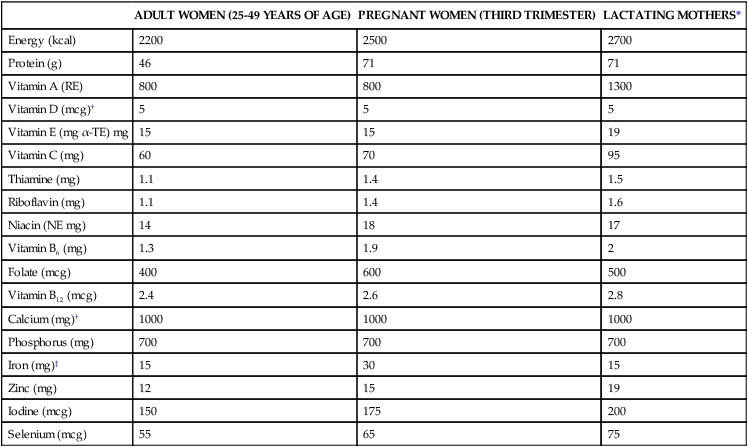

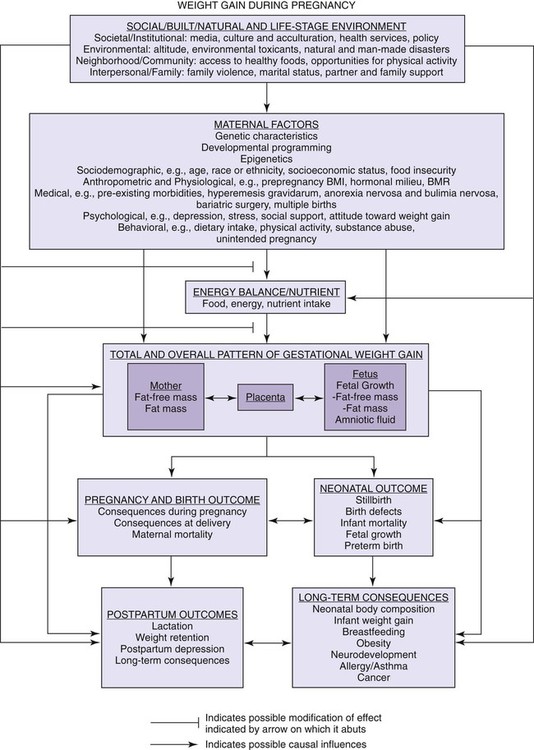

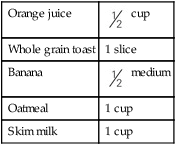

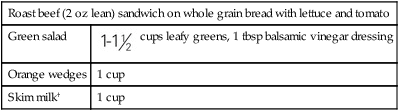

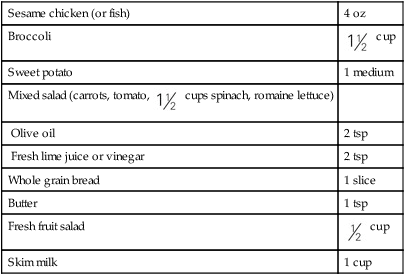

Chapters 11, 12, and 13 cover the topics of life span health promotion. These chapters not only address the basic nutrition requirements of pregnancy, infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood through older adulthood but also consider the factors that affect health promotion. As presented in Chapter 1, the goal of health promotion is to increase the level of health of individuals, families, and communities. Health promotion strategies often focus on lifestyle changes leading to new, positive health behaviors. Profound changes in maternal metabolism occur during pregnancy, and successful adaptation to these changes is necessary for a favorable pregnancy outcome. The basal metabolic rate (BMR) rises during pregnancy by as much as 15% to 20% by term. This increase is caused by the increased oxygen needs of the fetus and the maternal support tissues. There are alterations in maternal metabolism of protein, carbohydrate, and fat. The fetus prefers to use glucose as its primary energy source. Changes occur in maternal metabolism to accommodate this need of the fetus. The adaptation allows the mother to use fat as the primary fuel source, thus permitting glucose to be available to the fetus.1 Increased macronutrient and micronutrient intake by the mother during pregnancy ensures that these increased metabolic needs are met. There are three components to maternal weight gain: (1) maternal body composition changes, including increased blood and extracellular fluid volume; (2) the maternal support tissues, such as the increased size of the uterus and breasts; and (3) the products of conception, including the fetus and the placenta. Inadequate weight gain by the mother during pregnancy suggests she may not have received the proper nutrients during pregnancy. Poor weight gain may then lead to intrauterine growth retardation in the infant. Infants born small for gestational age (SGA) or low birth weight are more likely to require prolonged hospitalization after birth or be ill or die during the first year of life. SGA is when an infant is born at a lower birth weight than expected for the length of gestation, while low birth weight is a weight less than 5.5 pounds (2500 g) at birth. Additionally, infant mortality rate, which in part reflects maternal weight gain, is regarded as one measure of a country’s health and well-being. Although the 2007 infant mortality rate for the United States (6.8 per 1000 live births) continued an all-time low first reached in 1996 (6.9 per 1000 live births),2 it still remains far greater than other developed countries. Infant mortality rates are higher among non-Hispanic black infants than among non-Hispanic white and Hispanic infants.2 There is strong evidence that the pattern of weight gain is just as important as the absolute recommended weight gains, as shown in Table 11-1. Failure to gain adequately during the second trimester of pregnancy is associated with poor infant birth weight, even if the net gain falls with in the recommendations. TABLE 11-1 NEW RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TOTAL AND RATE OF WEIGHT GAIN DURING PREGNANCY, BY PREPREGNANCY BMI *Calculations assume a 0.5-2 kg (1.1-4.4 lbs) weight gin in the first trimester (based on Siega-Riz et al., 1994; Abrams et al., 1995; Carmichael et al., 1997). From Institute of Medicine and National Research Council: Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines, Washington, DC, 2009, The National Academies Press. A balance must be struck regarding weight gain during pregnancy. Although women who are underweight or normal weight (as defined by body mass index [BMI]) are counseled to eat sufficiently to promote adequate gain, caution must be observed in counseling women who enter pregnancy overweight or obese. Overweight and obese women should gain enough weight to support the fetus and maternal support tissues but without increasing total body fat. There are increased risks for operative delivery, increased maternal postpartum weight, gestational diabetes, and other long-term health consequences when maternal weight goes beyond the guidelines, particularly among women who are obese before pregnancy.1 In addition, there may be subpopulations such as minorities and low-income women who need special guidance regarding weight gain during pregnancy. Figure 11-1 summarizes possible determinants and effects on gestational weight gain. The Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) recommend increases during pregnancy of all nutrients except vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K, phosphorus, fluoride, calcium, and biotin (Table 11-2). There are separate dietary recommendations for adolescents who are pregnant. TABLE 11-2 DRIs TO MEET NEEDS OF PREGNANCY AND LACTATION *During the first 6 months of lactation. ‡The increased iron requirement for pregnancy cannot be met by the usual American diet or from body stores; thus a supplement of 30 to 60 mg of elemental iron is recommended. From Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board: Dietary DRI References: The essential guide to nutrient requirements, Washington, DC, 2006, The National Academies Press. It is difficult to estimate the true energy cost of pregnancy, but the best estimates place the total energy cost somewhere between 68,000 kcal and 80,000 kcal. The increase accommodates the rise in maternal BMR during pregnancy, as well as the synthesis and support of the maternal and fetal tissues.1 The current recommendation is for a woman to consume an extra 300 kcal per day during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Although she is eating for two, the expectant mother need not and should not double her food intake. An extra sandwich and a glass of milk can easily provide the additional 300 kcal per day, providing she was eating well before pregnancy. Personal preference may guide particular food choices to provide the extra kcal, as long as the foods are nutritious. What happens if a pregnant woman fails to increase her energy intake during pregnancy? The best-known example in the twentieth century occurred in Holland during World War II. Infants born during the famine of 1944 and 1945 had smaller birth weights and birth lengths when compared with infants born either before or after the famine.3 Recent research shows that when women who begin pregnancy in energy deficit (e.g., those who are chronically undernourished in developing countries) are provided with energy supplementation throughout the course of pregnancy, there is a positive effect on maternal weight gain and infant birth weight.4 On the other hand, some research suggests that women in the United States who are well nourished do not increase their total energy intake by a full 300 kcal per day and still have a positive pregnancy outcome. Most likely, in the third trimester, many women decrease their energy expenditure in pregnancy by decreasing activity, thereby giving a net increase in energy intake.5 Pregnancy is not a time to restrict kcal or to lose weight, even if the mother begins the pregnancy as overweight. This may be particularly important to emphasize to the adolescent population. The mother should be encouraged to eat at least the minimum number of servings recommended during pregnancy from MyPyramid (Box 11-1). The interactive MyPyramid Plan for Moms creates a personalized dietary food pattern based on height, weight, age, and other characteristics. Sample menus can be helpful in showing the pregnant woman how MyPyramid can be used (Box 11-2). The DRIs are increased during pregnancy for most vitamins and minerals. Vitamins of concern are vitamins A and D. While the RDA for vitamin A is 750 to 770 mcgRAE (Retinol Activity Equivalents) preformed vitamin A, the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) is set at 2800 to 3000 mcgRAE preformed vitamin A per day because of the potential for birth defects from excessive intake.6 Similarly, excessive vitamin D during pregnancy may cause birth defects so that the Adequate Intake (AI) (5 mcg per day) and UL (50 mcg per day) are the same for women regardless of physiological state.6 Micronutrient needs may be met with a balanced diet, with a few notable exceptions including folate and iron. All supplementation during pregnancy should be in the form of prenatal type multivitamin-mineral supplements as recommended by primary health care providers or dietitians. Substantial research has demonstrated that folate is important for the prevention of neural tube defects (NTDs) such as spina bifida and anencephaly, one of the most common congenital malformations in the United States. Approximately 2500 to 3000 infants are born with NTDs each year in the United States, with an equal number likely lost to pregnancy termination and additional unknown numbers of spontaneous abortions. The U.S. Public Health Service and the American Academy of Pediatrics now recommend all women of childbearing age who are capable of becoming pregnant receive a daily intake of 400 mcg of synthetic folic acid (from vitamin supplements, fortified grains, and other foods). Although fortification has been implemented, education continues to be needed to encourage awareness of folic acid intake by women of childbearing age. During pregnancy the DRI increases to 600 mcg dietary folate equivalents (DFE) per day.6 The RDA for iron during pregnancy is 27 mg per day. This level may be difficult to achieve with a normal diet, which maintains recommended fat and kcal guidelines. Therefore, all women should take a supplement with 30 mg ferrous iron daily beginning in the second trimester to prevent iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy.1 As discussed in Chapter 8, an unusual behavior associated with iron deficiency is pica. Pica is characterized by a hunger and appetite for nonfood substances including ice, cornstarch, clay, and even dirt. These substances contain no iron and may lead to loss of additional minerals, particularly when clay and dirt are consumed. Intestinal blockages caused by consumption of these substances may be life-threatening. Of particular concern is the practice of pica during pregnancy when the risk and implications of iron deficiency anemia are most severe. Although more common among African American women, pica has been diagnosed among all ethnic groups within all socioeconomic levels. A challenge to obstetric nurses is to elicit information about this type of dietary behavior when assessing clients. The AI for calcium is 1000 mg per day for women and 1300 mg per day for adolescents, neither of which is an increase over the nonpregnant state.6 Although calcium needs are great during pregnancy, particularly for mineralization of the fetal skeleton, changes occur in maternal calcium homeostasis, which results in an increase in intestinal calcium absorption. Many women, particularly adolescents, may not consume the AI for calcium before pregnancy. Women who are unable to consume rich sources of calcium may need to seek advice from a dietitian/nutrition specialist to determine whether supplements are necessary. Some pregnant women require particular attention through the course of pregnancy because of exposure to potential teratogens, problematic lifestyle behaviors, or development of medical conditions unique to pregnancy. Box 11-3 lists special needs populations of pregnant women. Whether a woman should refrain from caffeine consumption during pregnancy has been a matter of debate. Caffeine (1-, 3-, 7-trimethyxanthine) may alter deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and, in some individuals, may alter circulating levels of neurotransmitters and increase blood pressure.7 It has been argued that any or all of these effects may have direct adverse consequences on the developing fetus. However, there is enough evidence suggesting that caffeine is not a human teratogen, and even at modest doses (<300 mg/day or about 2 cups or less of coffee), there is no increased risk of spontaneous abortion or preterm labor. It doesn’t affect birth weight, gestational age, or fetal growth.7 There may be small reductions in birth weight at very high levels of consumption. The important issue may be that heavy use of nonnutritive substances such as coffee, tea, and cola may displace needed nutrients in the diet and thus interfere with prenatal development. Moderation of caffeine use during pregnancy as opposed to complete elimination is reasonable advice. This recommendation is consistent with a large body of animal data that show that consumption of large quantities of preformed vitamin A during pregnancy results in an excess of malformations such as anencephaly (defective brain development), cleft palate, spina bifida, webbed fingers or toes, and facial malformations. Vitamin A crosses the placenta by simple diffusion. Because it is fat soluble, the excess vitamin A can accumulate in the fetal tissues and may cause damage by interfering with cellular growth and differentiation during critical periods of development.8 The use of alcohol during pregnancy may produce fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) or fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) in the infant. Symptoms include central nervous systems defects and specific anatomic defects such as a low nasal bridge, short nose, flat midface, and short palpebral fissures (separation between the upper and lower eyelids) (Figure 11-2).

Life Span Health Promotion

Pregnancy, Lactation, and Infancy

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition During Pregnancy

Body Composition Changes during Pregnancy

Metabolic Changes

Weight Gain in Pregnancy

TOTAL WEIGHT

RATES OF WEIGHT GAIN*

GAIN

SECOND AND THIRD TRIMESTER

Prepregnancy BMI

Range in kg

Range in lbs

Mean (Range) in kg/week

Mean (Range) in lbs/week

Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2)

12.5-18

28-40

0.51 (0.44-0.58)

1 (1-1.3)

Normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2)

11.5-16

25-35

0.42 (0.35-0.50)

1 (0.8-1)

Overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2)

7-11.5

15-25

0.28 (0.23-0.33)

0.6 (0.5-0.7)

Obese (≥30.0 kg/m2)

5-9

11-20

0.22 (0.17-0.27)

0.5 (0.4-0.6)

Energy and Nutrient Needs during Pregnancy

ADULT WOMEN (25-49 YEARS OF AGE)

PREGNANT WOMEN (THIRD TRIMESTER)

LACTATING MOTHERS*

Energy (kcal)

2200

2500

2700

Protein (g)

46

71

71

Vitamin A (RE)

800

800

1300

Vitamin D (mcg)†

5

5

5

Vitamin E (mg α-TE) mg

15

15

19

Vitamin C (mg)

60

70

95

Thiamine (mg)

1.1

1.4

1.5

Riboflavin (mg)

1.1

1.4

1.6

Niacin (NE mg)

14

18

17

Vitamin B6 (mg)

1.3

1.9

2

Folate (mcg)

400

600

500

Vitamin B12 (mcg)

2.4

2.6

2.8

Calcium (mg)†

1000

1000

1000

Phosphorus (mg)

700

700

700

Iron (mg)‡

15

30

15

Zinc (mg)

12

15

19

Iodine (mcg)

150

175

200

Selenium (mcg)

55

65

75

Energy

Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation

Folate

Iron

Calcium

Nutrition-Related Concerns

Caffeine

Drugs

Alcohol

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Life Span Health Promotion: Pregnancy, Lactation, and Infancy

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

cup

cup medium

medium

cups leafy greens, 1 tbsp balsamic vinegar dressing

cups leafy greens, 1 tbsp balsamic vinegar dressing

cup

cup cups spinach, romaine lettuce)

cups spinach, romaine lettuce) cup

cup

cup with skim milk (

cup with skim milk ( cup)

cup) cup) with nonfat yogurt (

cup) with nonfat yogurt ( cup)

cup)