Laura R. Mahlmeister, PhD, MSN, RN After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Differentiate among the three major categories of law on which nursing practice is established and governed. 2. Analyze the relationship between accountability and liability for one’s actions in professional nursing practice. 3. Outline the essential elements that must be proven to establish a claim of negligence or malpractice. 4. Distinguish between intentional and unintentional torts in relation to nursing practice. 5. Identify causes of nursing error and patient injury that have led to claims of criminal negligence. 6. Incorporate fundamental laws and statutory regulations that establish the patient’s right to autonomy, self-determination, and informed decision making in the health care setting. 7. Incorporate laws and statutory regulations that establish the patient’s right to privacy and privacy of health records. 8. Complete the critical thinking exercises at the end of the chapter to consolidate understanding of the relationship between nursing practice and the law. Being responsible for one’s actions; a sense of duty in performing nursing tasks and activities. Written or verbal instructions created by the patient describing specific wishes about medical care in the event he or she becomes incapacitated or incompetent. Examples include living wills and durable powers of attorney. Body of written opinions created by judges in federal and state appellate cases; also known as judge-made law and common law. A category of law (tort law) that deals with conduct considered unacceptable. It is based on societal expectations regarding interpersonal conduct. Common causes of civil litigation include professional malpractice, negligence, and assault and battery. Law that is created through the decision of judges as opposed to laws enacted by legislative bodies (i.e., Congress). A type of liability in which damages may be apportioned among two or more defendants in a malpractice case. The extent of liability depends on the defendant’s relative contribution to the patient’s injury. Negligence that indicates “reckless and wanton” disregard for the safety, well-being, or life of an individual; behavior that demonstrates a complete disregard for another, such that death is likely. Monetary compensation the court orders paid to a person who has sustained a loss or injury to his or her person or property through the misconduct (intentional or unintentional) of another. The individual who is named in a person’s (plaintiff’s) complaint as responsible for an injury; the person who the plaintiff claims committed a negligent act or malpractice. A process in which the patient’s primary provider (physician or advanced practice nurse) gives the patient, and when applicable, family members, complete information about unanticipated adverse outcomes of treatment and care. Durable power of attorney for health care An instrument that authorizes another person to act as one’s agent in decisions regarding health care if the person becomes incompetent to make his or her own decisions. A failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve a specific aim. A legal concept that means extreme carelessness showing willful or reckless disregard for the consequences to a person (patient). Legal doctrine by which a person is protected from a lawsuit for negligent acts or an institution is protected from a suit for the negligent acts of its employees. Being legally responsible for harm caused to another person or property as a result of one’s actions; compensation for harm normally is paid in monetary damages. Laws that establish the qualifications for obtaining and maintaining a license to perform particular services. Persons and institutions may be required to obtain a license to provide particular health care services. Failure of a professional to meet the standard of conduct that a reasonable and prudent member of his or her profession would exercise in similar circumstances that results in harm. The professional’s misconduct is unintentional. Failure to act in a manner that an ordinary, prudent person (either a layperson or professional) would act in similar circumstances, resulting in harm. The failure to act in a reasonable and prudent manner is unintentional. The complaining person in a lawsuit; the person who claims he or she was injured by the acts of another. An injury caused by medical management rather than the patient’s underlying condition. An adverse event attributable to error is a preventable adverse event. Monetary compensation awarded to an injured person (patient) that goes beyond that which is necessary to compensate for losses (e.g., the ability to function, death, income) and is intended to punish the wrongdoer. Legal doctrine applicable to cases in which the provider (i.e., the physician) had exclusive control of events that resulted in the patient’s injury; the injury would not have occurred ordinarily without a negligent act; a Latin phrase meaning “the thing speaks for itself.” Legal doctrine that holds an employer indirectly responsible for the negligent acts of employees carried out within the scope of employment; a Latin phrase meaning “let the master answer.” Process of identifying, analyzing, and controlling risks posed to patients; involves human factor and incident analysis, changes in systems operations, and loss control and prevention. As defined by The Joint Commission, an unintended adverse outcome that results in death, paralysis, coma, or other major permanent loss of function. Examples of sentinel events include patient suicide while in a licensed health care facility, surgical procedure on the wrong organ or body side, or a patient fall. In civil cases, the legal criteria against which the nurse’s (and physician’s) conduct is compared to determine whether a negligent act or malpractice occurred; commonly defined as the knowledge and skill that an ordinary, reasonably prudent person would possess and exercise in the same or similar circumstances. Law enacted by a legislative body; separate from judge-made or common law. A legal doctrine, sometimes referred to as absolute liability, which can be imposed on a person or entity (e.g., a hospital) without proof of carelessness or negligence. Legal doctrine in which a person or institution is liable for the negligent acts of another because of a special relationship between the two parties; a substituted liability. Additional resources are available online at: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Cherry/ VIGNETTE Mr. Jones is enrolled in a non-profit health insurance cooperative (Feel-Well Insurance). “Feel-Well” may not reimburse the for-profit hospital for Mr. Jones’s visit if it is determined that his condition was not a true emergency after review by the cooperative’s utilization review department. In that case, Mr. Jones will have to pay out of pocket for the medical evaluation and care received in the ED. In this cost-conscious health care environment, the nurses in the ED are well aware of the financial losses their hospital has recently suffered as a result of unpaid emergency services. Nurses in this facility are expected to contribute to the facility’s success in reducing operating costs. Questions to Consider While Reading This Chapter 1. What is nurse Clark’s legal duty in this situation? 2. What legal principles underlie the nurse’s obligations to the patient? 3. What laws, if any, would govern the nurse’s decision-making process in this case? 4. If Mr. Jones is not evaluated or treated and suffers a myocardial infarction while driving to Community Hospital, who would be legally accountable for his injuries? The nurse? The for-profit hospital? The HMO that may not have reimbursed for services? The preceding vignette highlighted a growing clinical dilemma that nurses face in the complex ever-changing health care system. Financial considerations may conflict with clinical concerns for patient well-being. In an increasingly complex health care environment, the nurse’s ability to make appropriate decisions about the provision of patient care services is assisted by a sound knowledge of the laws governing practice. In the case of Mr. Jones, triage, assessment, medical evaluation, and treatment are regulated by a federal law known as the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) (COBRA, 42 U.S.C. 1395dd). There also may be a specific state law regarding essential care and transport of patients in EDs. Additionally, sections of the state’s nurse practice act describing the professional conduct of the RN would assist nurse Clark in managing this clinical problem. Financial concerns, such as pressure exerted on the nurse to reduce the cost of care, become a secondary consideration for the nurse with this baseline knowledge of the law. The actions of all individuals are regulated through two systems of principles known as laws and ethics. Laws enforce a minimal level of conduct by imposing penalties for violations of acceptable behavior (Griffith and Tengnah, 2008). Laws are expressed in terms of “must” and “shall” and are based on a society’s interest in prohibiting or controlling certain behaviors. Ethics are described in terms of “should” and “may” and address beliefs about appropriate behaviors within a societal context (Westrick and Dempski, 2008). Chapter 9 presents an in-depth discussion about nursing ethics. Along with ethics, professional nursing conduct also is regulated by a variety of laws. The two major sources of law are statutory law and common law. The standards for professional nursing practice are in great part derived from statutory as well as common law. The following section deals with statutory law and describes how it governs and indirectly influences nursing practice. The terms law and statute are used interchangeably in this chapter. Laws that are written by legislative bodies, such as Congress or state legislatures, are enacted as statutes. The previously mentioned law, the EMTALA, is an example of a federal statute. Violation of law is a criminal offense against the general public and is prosecuted by government authorities. Crimes are punishable by fines or imprisonment. The list of federal and state statutes that govern nursing practice has multiplied over the past 25 years. Nurses at all levels of practice must develop a greater depth and breadth of knowledge about laws related to patient safety, professional practice, their specific practice setting (i.e., the ED in the case of the EMTALA), and health care systems in general. Ignorance of the law is never a defense when a nurse violates a health care statute. A nurse who violates the law is subject to penalties, including monetary fines, suspension or revocation of his or her license, and even imprisonment in some instances (Kazmier, 2008). Federal laws have a major effect on nursing practice, mandating a minimal standard of care in all health care settings that receive federal funds (i.e., reimbursement for treatment of Medicare patients under the Rules of Participation of Hospitals in Medicare). Medicare is administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and has the authority to establish new rules and regulations to enhance patient safety and quality, and reduce the cost of care. In 2008, the CMS issued new rules that halt payment to hospitals for treatment of preventable patient complications and injuries, often referred to as “never events.” The CMS identified 10 categories of hospital-acquired conditions that studies have demonstrated are “reasonably preventable” (CMS, 2008). Box 8-1 lists the 10 categories of adverse events that are subject to nonpayment. The new rules were enacted in 2009 and have already had a significant impact on hospital nursing care through the introduction of evidence-based practices to prevent complications such as falls, infections, and the development of stage III and stage IV pressure ulcers. The major revisions the CMS proposed in the Rules of Participation for Hospitals in Medicare took effect July 16, 2012. Under the new Rules, nurses will be required to develop greater expertise in the provision of evidence-based patient care, case management, and discharge planning (IOM, 2010). Legal concerns have been raised about a possible increase in malpractice claims related to hospital-acquired conditions. It may be more difficult for a hospital to defend a malpractice claim if “strict liability” is applied to these hospital-acquired events (Vonwinkel, 2008). Strict liability imposes legal responsibility for damages or injury, even if the person (the hospital in the case of hospital-acquired conditions) is not “strictly” at fault or negligent. This federal statute, often referred to as the “antidumping” law, was enacted in 1986 to prohibit the refusal of care for indigent and uninsured patients seeking medical assistance in an ED (Moy, 2012). This law also prohibits the transfer of unstable patients, including women in labor, from one facility to another. The law states: The EMTALA is applicable to people coming to non-ED settings, such as urgent care clinics. It even governs the transfer of patients from an inpatient setting to a lower level of care in some parts of the United States (Roberts v. Galen of Virginia, Inc., 1997). Significant penalties can be levied against a facility that violates the EMTALA, including a $25,000 to $50,000 fine (not covered by liability insurance). The federal government also can revoke the facility’s Medicare contract, and this could result in a major loss of revenue for the institution or even insolvency. Many legitimate concerns that nurses have about the discharge or transfer of patients could be promptly addressed if the nurse had a solid understanding of the EMTALA. A recent case illustrates the importance of understanding the EMTALA. In Love v. Rancocas Hospital (2006), a woman was transported by ambulance to the ED after losing consciousness at home. She had a history of hypertension and continued to have high blood pressure readings in the ED. The woman also fell off the bed twice while being monitored, but the ED nurse did not report this to the physician. The nurse received a discharge order from the physician and sent the woman home in an unstable condition, thus violating the stabilization requirement of the EMTALA. The woman returned 2 days later after experiencing a stroke. Understanding the EMTALA is not a daunting task for nurses engaged in the triage and medical screening of patients presenting to the ED or obstetric triage department. Nursing journals have published many articles about the EMTALA and the nurse’s role in upholding this statute (Angelini and Mahlmeister, 2005; Bond, 2008; Caliendo et al, 2004). The intent of this law is to end discrimination against qualified persons with disabilities by removing barriers that prevent them from enjoying the same opportunities available to persons without disabilities. Court cases have established that as a place of public accommodation, a health care facility must provide reasonable accommodation to patients (and family members) with sensory disabilities, such as vision and hearing impairment (Abernathy v. Valley Medical Center, 2006; Boyer v. Tift County Hospital, 2008). In another case (Parco v. Pacifica Hospital, 2007), a nurse was caring for a ventilator-dependent quadriplegic patient who was unable to speak or use his call light. She requested a special pillow that activated the patient’s call light when he turned his head, but was told that all the pillows were in use. The patient subsequently experienced three episodes of respiratory distress that he was unable to alert the nurse about, and could only hope that someone would discover his problem before he suffered brain damage or death (Snyder, 2007a). The patient sued for emotional distress and mental anguish. The court affirmed that the ADA requires hospitals to provide assistive devices to patients with communication problems related to a disability. The hospital settled the lawsuit for $295,000. With the continued increase in the number of nurses using social media such as blogs, social networking sites, video sites, and online chat rooms and forums, a patient’s right to privacy is threatened. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) has published a brochure, “A nurse’s guide to the use of social media” (NCSBN, 2011a). The publication reviews the benefits and risks of using social media in the workplace or bringing workplace issues to social media sites during free time. The release of private health data, either inadvertent or intentional, is a violation of the HIPAA and is punishable by significant fines and a term of imprisonment. It may also result in suspension or revocation of the nurse’s license. Civil actions may arise from a violation of patient confidentiality, alleging failure to maintain security of protected patient health data, unprofessional conduct, and violation of hospital policies and procedures that restrict access to patient information on a “need to know” basis. Posting photographs or videotapes of patients, or even ostensibly unidentifiable body parts is expressly forbidden and also violates the American Nurses Association Code of Ethics for Nurses (2001, reaffirmed 2010). Discussing conflicts with managers or coworkers on social networking sites or posting unauthorized photos or videos of professional colleagues opens the nurse to claims of invasion of privacy, slander, intentional infliction of harm, and emotional distress, among other things. Further risks to one’s livelihood and future employment as a nurse are presented when the nurse publicly airs dissatisfaction with his or her employer or discusses problems at work that make the employer vulnerable to ridicule or loss of reputation in the community or larger health care arena. Although NPAs vary from state to state, they usually contain the following information: • Description of professional nursing functions • Standards of competent performance • Behaviors that represent misconduct or prohibited practices • Grounds for disciplinary action • Fines and penalties the licensing board may levy when an NPA is violated For further exploration, excerpts from three separate state NPAs can be found online (http://evolve.elsevier.com/Cherry/) to illustrate how an NPA defines the scope of practice for nurses. Surprisingly, many nurses are not even aware that the NPA is a law, and they unknowingly violate aspects of this statute (NCSBN, 2011b). They are not familiar with the administrative rules and regulations enacted by the licensing board. This is an unfortunate lapse because these administrative rules and regulations answer crucial questions that nurses have about the day-to-day aspects of practice and unusual occurrences. For example, the increasing complexity of health care requires effective communication, collaboration, and planning of care among many licensed health team members. Rules promulgated by the Ohio Board of Nursing Section 4723.03 related to the competent practice as an RN direct the nurse in appropriate reporting and consultation. “A registered nurse shall in a timely manner: • Implement any order for a client unless the registered nurse believes or should have reason to believe the order is: • Clarify any order for a client when the registered nurse believes or should have reason to believe the order is: [a through e as delineated in (1)]” Each nurse should own a current copy of the NPA and the licensing board’s administrative rules and regulations. The nurse also must know how to access the licensing board online and by telephone in order to clarify issues related to nursing practice. The dramatic changes occurring in health care often lead to uncertainty among nurses about which functions constitute the exclusive practice of registered nursing and which patient care tasks may be lawfully delegated to a licensed practical nurse/licensed vocational nurse (LPN/LVN) or unlicensed assistive personnel. The NPA and licensing board rules and regulations provide essential information that clarifies these important questions. In 2008, the Texas Board of Nursing approved a new rule requiring all nurses to take and pass a Nursing Jurisprudence Exam prior to initial licensure. The exam tests knowledge regarding nursing board statutes, rules, position statements, disciplinary action, and other resource documents accessible on the Texas board website (http://bon.state.tx.us/index.html). Nurses may also have questions and concerns regarding the legal aspects of floating to unfamiliar units. An NPA provides information regarding the scope of practice, required competencies, and the responsibilities of a nurse who accepts an assignment or agrees to carry out any task or activity in the clinical setting. The NPA broadly defines the practice of registered nursing in accordance with nursing’s rapidly evolving functions. In recent years, with the expansion of basic nursing functions and the development of advanced nursing practice, many states have revised their NPAs. Licensing boards also have been authorized in some states to provide guidelines for the development of “standardized procedures.” Standardized procedures are a legal means by which RNs may expand their practice into areas traditionally considered to be within the realm of medicine. The standardized procedure actually is developed within the facility where the expanded nursing functions have been approved. It is developed in collaboration with nursing, medicine, and administration. An example of a standardized procedure is a written protocol authorizing a nurse to implement a peripherally inserted venous catheter for patients in the neonatal intensive care unit. The NCSBN provides additional online resources for nurses covering diverse topics, including licensure and regulation (NCSBN, 2011b). State legislatures have given licensing boards the authority to hear and decide administrative cases against nurses when there is an alleged violation of an NPA or the nursing board’s rules and regulations. Nurses who violate the NPA or board’s administrative rules and regulations are subject to disciplinary action by the board. Research indicates an increase in the number of consumer complaints to licensing boards related to nursing misconduct, and disciplinary actions more than doubled from 1996 to 2006 (Kenward, 2008). Table 8-1 provides a synopsis of the licensing board procedure when a complaint is made about a nurse. Courts have consistently affirmed board of nursing decisions to restrict, suspend, or revoke the nurse’s license when nurses have challenged the decision. TABLE 8-1 LICENSING BOARD PROCEDURE WHEN A COMPLAINT IS FILED CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; NPA, nurse practice act. Box 8-2 presents the more common grounds for disciplinary action by state boards of nursing. Penalties that licensing boards may impose for violations of an NPA include the following: An estimated 10% to 15% of RNs in the United States are chemically dependent (NCSBN, 2011c). The majority of disciplinary actions by licensing boards are related to misconduct resulting from chemical impairment, including the misappropriation of drugs for personal use and the sale of drugs and drug paraphernalia to support the nurse’s addiction. When a nurse’s license is limited or suspended because of problems related to chemical impairment, the ability to practice in the future often is predicated on successful completion of a drug rehabilitation program and evidence of abstinence. An increasing number of state licensing boards have established programs to guide nurses through the process of rehabilitation to re-establish licensure. Inadequate and often unsafe nurse-patient ratios continue to plague nursing. A growing body of evidence confirms a strong association between nurse-patient ratios and patient outcomes (Furukawa et al, 2011; Needleman et al, 2011; Penoyer, 2010). The American Nurses Association (ANA) launched its “Safe Staffing Saves Lives Campaign” in 2008, publishing the results of a poll conducted to examine nurses’ perceptions of staffing problems (ANA, 2009a). More than 50% of respondents were considering leaving their current nursing position, and 42% indicated that the reason for leaving was associated with inadequate staffing. Another study surveyed direct care nurses about nursing errors of omission. Greater than 70% of respondents reported the inability at times to plan and implement required care and intervene in a timely manner. Forty-four percent of respondents missed essential assessments (Kalisch et al, 2009). Eighty-five percent of the nurses indicated that lack of human resources (nurse and support staff) was the primary reason for omissions in essential components of the nursing process. Nurse staffing is influenced to some degree by federal law, through the Rules of Participation for Hospitals in Medicare, and, increasingly, by state laws. Hospitals risk losing federal Medicare and Medicaid funding for a confirmed pattern of understaffing, which has not been properly addressed by managers and administrators. For example, in 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) cited several Texas hospitals for understaffing, in part due to increased patient census. (Caramenico, 2011). The CMS placed the hospitals in “immediate jeopardy” of losing their funding. Hospital administrators and clinical leaders must prepare a corrective action plan and submit it to the CMS within a specified time when cited by the CMS for safety violations such as unsafe staffing levels. Nurses can positively affect nurse staffing levels when armed with knowledge regarding federal and state laws. When concerns about work-related issues arise (e.g., a reduction in RN staffing, mandatory overtime, or replacement of RNs with LVNs-LPNs or unlicensed assistive personnel), the first question the nurse asks and answers should be, “Is this legal?” (Brooke, 2009). In 1999, California became the first state to enact a law (California Assembly Bill 394) that mandates the establishment of minimum nurse-patient ratios in acute care facilities. The law took effect in January 2004 and set minimum nurse-patient ratios in critical care units, step-down and medical-surgical units, and maternity departments. No other state has followed California’s lead in establishing nurse-patient ratios, but by 2011, seventeen states had enacted laws that regulate or restrict mandatory overtime for nurses (ANA, 2012). The ANA has also reintroduced the RN Safe Staffing Act for the 2011-2012 session of Congress. It would require hospitals that participate in Medicare to implement staffing plans, established by a committee composed of a majority of direct-care nurses for each nursing unit and shift. An increasing number of lawsuits against health care facilities have set forth claims of corporate negligence for inadequate staffing or “understaffing” when adverse outcomes occur. A jury awarded a $1.7 million verdict against a nursing home for the death of a resident who fell from her wheelchair. Evidence revealed that there was a widespread pattern of understaffing at the nursing home (Sunbridge Healthcare Corp. v. Penny, 2005). In a second case, Penalver v. Living Centers of Texas (2004), the director of nursing and the facility’s administrator were found negligent in the death of a resident who fell from her wheelchair. Evidence was presented during the trial that there had been more than 800 other falls in the facility as a result of severe and chronic understaffing (Snyder, 2004a). The jury awarded her family $856,000. In 2006, another jury awarded $240,000 in punitive damages (out of a total award of $400,000) against a nursing home because understaffing at the facility was considered an aggravating factor in a patient’s death (Miller v. Levering Regional Healthcare Center, 2006). The patient was 91 years of age and suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. The resident (patient) was left unattended and fell, hitting her head, and subsequently died of her injuries. The court records contained adequate evidence that the facility knew it had a chronic understaffing problem and that the problem directly led to the woman’s death (Snyder, 2006). The director of nursing was also found negligent for failing to comply with Medicare guidelines that required the facility to provide sufficient staffing. The federal government and states seek to protect at-risk individuals (children and older adults) by requiring nurses and other health care providers to report specific types of suspected or actual patient-client injury, abuse, or neglect (Buppert and Klein, 2008). Boards of nursing are created to protect the public from unethical, incompetent, or impaired nursing practice. Some states have enacted statutes that mandate nurses to report unsafe, illegal, or unethical practices of nursing colleagues or physicians. With these mandates and protections in mind, the following case illustrates the adverse consequences that nurses may still face when reporting professional colleagues. In 2009, two Texas nurses anonymously reported concerns they had about a physician to the Texas Medical Board, after failing to obtain a satisfactory response to complaints they filed with hospital administrators. One of the nurses served as the compliance officer, and the other was in charge of quality improvement at the hospital where the physician had been granted staff privileges. The nurses alleged, among other things, that the physician provided substandard treatment of patients (Lowes, 2010a). When the Medical Board notified the physician that it had received a complaint, he asked the county sheriff, a former patient and acknowledged friend, to investigate the matter. The sheriff obtained a search warrant to seize the nurses’ computers, and discovered the source of the complaint. The hospital fired the nurses, and the district attorney charged them with felony misuse of official information with intent to harm (the physician). The nurse who actually authored the report on her computer faced a 10-year prison sentence if convicted. Both the ANA and the Texas Nurses Association (TNA) objected strenuously to the criminal prosecution of the nurses and established a defense fund to support the nurses and “to support the legal rights of every practicing nurse in Texas to advocate for patients” (TNA, 2009). The ANA issued a News Release, “American Nurses Association and Texas Nurses Association speak out against wrongful prosecution of Winkler County nurses” (ANA, 2009b). The district attorney dropped the charges against one nurse but took the second nurse to trial (the nurse who authored the report to the Medical Board). The jury found the nurse not guilty in less than 1 hour of deliberation. After the trial, both nurses filed a civil lawsuit in federal court against the hospital, physician, and county officials, charging, among other things, vindictive prosecution and violation of their First Amendment Rights (freedom of speech). In 2010, the defendants agreed to pay the two nurses $375,000 each for loss of income, and future loss of earnings (Lowes, 2010b). The Texas Department of State Health Services assessed a $15,850 fine on Winkler County Memorial Hospital in part for failure to properly supervise the physician in the case, and for terminating the nurses. In January 2011, a grand jury in Winkler County indicted the sheriff, two county officials, a former hospital administrator, and the physician on criminal charges including felony misuse of official information, retaliation, and official oppression. The sheriff and the district attorney who prosecuted the nurses were convicted of retaliation. The sheriff was sentenced to 100 days in jail and was required to permanently surrender his officer’s license. The district attorney was sentenced to 120 days in jail and 10 years of probation, and was fined $6000. He has been suspended from office and is appealing his conviction. The former hospital administrator who fired the nurses pled guilty to one count of abuse of official capacity, a misdemeanor, and was sentenced to 30 days in jail. Finally, in November 2011, the physician pled guilty to retaliation against the nurses and felony misuse of information. He was sentenced to 2 months in jail and 5 years of probation. He was fined $5000 by the Texas Medical Board and was required to surrender his medical license. As part of the plea agreement, the physician will no longer face a felony aggravated perjury charge for allegedly lying under oath at the nurse’s criminal trial when he denied knowing how the sheriff obtained names of and contact information for patients in order to question them about who may have filed the complaint (Blaney, 2011). This case provides sobering evidence of the potential retaliatory responses the nurse may face when reporting incompetent, illegal, or unethical conduct. The nursing literature provides nurses with recommendations and guidelines when considering the duty to report and its consequences (Philipsen and Soeken, 2011; Lachman, 2008; Buppert, 2008). An increasing number of legal experts advise the nurse to seek the services of an attorney who specializes in reporting and whistle-blowing activities for nurses before making a decision to report. The types of conduct the boards of nursing require nurses to report vary from state to state. Nurses can access the specific requirements for reporting nurse coworkers at their board of nursing website. Some states require nurses and providers to report victims of domestic or interpersonal violence, whether or not the victim (patient) consents. Nurses can access current information from the state regarding reporting requirements under family or domestic violence statutes. For a list of family violence statutes compiled by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (2012), visit http://www.aaos.org/about/abuse/ststatut.asp. Certain specifiable communicable diseases must also be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) such as bubonic plague, anthrax, and botulism. (For the list of reportable diseases, visit http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/.) State law may also require nurses to report injuries resulting from the use of weapons, attempts to harm oneself, or impaired driving (Buppert and Klein, 2008). Nurse managers and administrators are responsible for ensuring that reports made by direct care nurses are forwarded to the appropriate legal authorities. Nurse leaders who fail in this duty may face criminal charges, claims of negligence, and disciplinary action by the nursing board (Hudspeth, 2008). In 1973, the U.S. Congress enacted the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, which mandates all states to meet specific uniform guidelines to qualify for federal funding of child abuse programs. All 50 states and the District of Columbia have created laws that require reporting of specific health problems and the suspected or confirmed abuse of infants or children. Nurses often are explicitly named within the context of these statutes as one of the groups of designated health professionals who must report the specified problems under penalty of fine or imprisonment. Nurses need not fear legal reprisal from individuals or families who are reported to authorities in suspected cases of abuse. Most legislatures have granted immunity from suit within the context of the mandatory reporting statute. There is also a long history of court decisions shielding the nurse from civil claims by parents or guardians when that report is made in good faith, and in compliance with federal and state laws. The case of Heinrich v. Conemaugh Valley Memorial Hospital (1994) upheld this doctrine of immunity. The family of an injured child initiated a lawsuit against a hospital that reported suspected child abuse after a state investigation found them innocent of the charge. The court ruled that the hospital and the physician who made the report in “good faith” were immune from litigation under the Pennsylvania Child Protective Service Law that required reports of suspected child abuse. In a Missouri case, a nurse failed to report a suspected case of child abuse to that state’s division of family services and to the physician in charge of her ED as required by law. She was charged with two misdemeanors that could have resulted in punishment of up to 2 years in prison and $2000 in fines, if she was convicted (Goldsmith, 2003). In 2004, the Supreme Court of Missouri reversed a lower court decision to dismiss the case, and the nurse still faced misdemeanor charges. Finally, in October 2004, the county prosecutor dropped all charges against the nurse. Although this case settled favorably for the nurse, the nurse spent 2 years defending the charges with the assistance of attorneys. (Details of the case can be found at http://springfield.news-leader.com/specialreports/dominicjames/0804-NurseinDom-148351.html and http://springfield.news-leader.com/columnists/overstreet/1107-FriendsofL-220780.html.)

Legal Issues in Nursing and Health Care

Chapter Overview

Sources of Law and Nursing Practice

Statutory Law

Federal Statutes

Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Law (COBRA, 42 U.S.C. 1395dd)

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (Public Law No. 101-336, 42 U.S.C. Section 12101)

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (Public Law No. 104-191)

State Statutes

State Nurse Practice Act and Board of Nursing Rules and Regulations

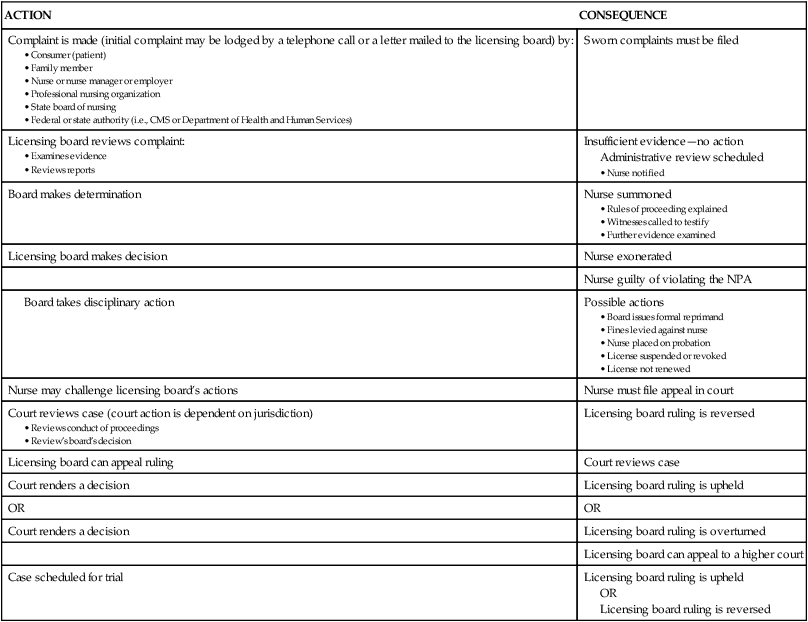

Violations of an NPA

ACTION

CONSEQUENCE

Complaint is made (initial complaint may be lodged by a telephone call or a letter mailed to the licensing board) by:

Sworn complaints must be filed

Licensing board reviews complaint:

Insufficient evidence—no action

Administrative review scheduled

Board makes determination

Nurse summoned

Licensing board makes decision

Nurse exonerated

Nurse guilty of violating the NPA

Possible actions

Nurse may challenge licensing board’s actions

Nurse must file appeal in court

Court reviews case (court action is dependent on jurisdiction)

Licensing board ruling is reversed

Licensing board can appeal ruling

Court reviews case

Court renders a decision

Licensing board ruling is upheld

OR

OR

Court renders a decision

Licensing board ruling is overturned

Licensing board can appeal to a higher court

Case scheduled for trial

Licensing board ruling is upheld

OR

Licensing board ruling is reversed

Nurse-Patient Ratios and Mandatory Overtime Statutes

Reporting Statutes

Child Abuse Reporting Statutes

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Legal Issues in Nursing and Health Care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access