Knowledge is the best way to prevent poor patient and professional outcomes. Thus, knowledge is the best offense as well as the best defense.

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Discuss various sources and types of laws.

• Relate the Nurse Practice Act to the governance of your profession.

• Understand the functions of a state board of nursing.

• Describe your responsibilities for obtaining and maintaining your license.

• Research and discuss scope of practice limitations on your license.

• Be able to identify the elements of nursing negligence and how each element is proven in a negligence claim.

• Incorporate an understanding of legal risks into your nursing practice and recognize how to minimize these risks.

• Discuss the concerns surrounding criminal charges in nursing practice.

• Identify legal issues involved in the medical record and your documentation, including the use of electronic medical records.

• Understand legal concepts such as informed consent and advance directives.

• Take an active role in improving the quality of health care as required by legal standards.

• Participate as a professional when dealing with nurses who are impaired or functioning dangerously in the work setting.

• Discuss the concerns surrounding at least two legal issues in nursing practice.

Generally speaking, laws are “rules of human conduct” designed to keep civilized societies from falling into anarchy. A law is a prescriptive or proscriptive rule of action or conduct promulgated by a controlling authority such as government. Because laws have binding legal force and are meant to be obeyed, failure to follow the law may subject you to a wide variety of legal consequences. The Latin phrase ignorantia legis neminem excusat means “ignorance of law excuses no one.” It is important for all persons, including nurses, to know, understand and follow the law as it relates to their personal and professional lives.

There are many laws from a variety of sources that directly and indirectly impact the practice of nursing. Understanding these laws can have a profound effect on the way you practice nursing and may help ensure safe nursing practice. This chapter is an important start in becoming a legally educated nursing professional. Your journey does not stop here, however, because the law is always evolving and under constant scrutiny and challenge. Nursing professionals must assume ongoing responsibility for keeping up with relevant changes in the federal, state, and local laws that govern nursing practice.

Sources of Law

Where Does “the Law” Come From?

Have you ever wondered where the law comes from? Laws can be created by regulatory, legislative, and litigation processes involving different branches of government (executive, legislative, and/or judicial). There are several primary and secondary sources of law that directly and indirectly impact the practice of nursing including constitutional law, statutory law, common law, administrative law, tort law, contract law, and criminal law.

What Is Constitutional Law?

The U.S. Constitution is the supreme law of the land. Constitutional law refers to the power, privileges, and responsibilities stated in, or inferred from, the U.S. Constitution as well as state constitutions. Constitutions prescribe the power and responsibilities of federal and state governments. For example, the powers of the federal government are defined in Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. These powers include such things as the power to coin money, the power to establish a uniform rule of naturalization, the power to declare war, the power to tax and spend, and the power to regulate interstate commerce. Medicare and Medicaid were enacted through the spending powers as the federal government collects the taxes and then spends them as distributions to the states to subsidize their Medicaid programs or directly to hospitals and providers as Medicare payments. The right to privacy is an example of a right inferred from the Constitution.

The Tenth Amendment to the Constitution states, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” This means the powers of the state government include anything and everything that is not specifically described as being a power of the federal government. These powers, referred to as “police powers,” include the power to license professionals, including nurses, and generally provide for public health and safety of the community. States may not pass laws or institute rules that conflict with constitutionally granted rights or powers.

What Is Statutory Law?

Statutory law is an important source of law. Statutes are created by federal, state, and local legislatures, which are comprised of elected officials who have been granted the power to create laws. It would be an impossible feat for governments to anticipate all possible scenarios in which a statute might be needed to regulate human conduct. Therefore, statutes are often written broadly enough to be applicable in a variety of situations. Courts must apply statutes, if available, to the facts of a case. If no statute exists, courts defer to common law (see below).

Statutory definitions are one of the most important parts of a statute. There you can find what the authors of the statute mean when they use a certain word. Because we all use words differently, a more precise understanding is necessary when reading and understanding statutory laws. (Box 20.1 lists definitions of common legal terms.) When a statute is vague or unclear, courts must engage in statutory interpretation to determine the legislature’s intent.

What Is Administrative Law?

As agents for the executive branch of federal and state government, administrative agencies protect the public health and welfare. Administrative law is made by administrative agencies that have been granted the authority to pass rules and regulations and render opinions, which usually explain in more detail the state statutes on a particular subject.

The administrative agency that is generally most familiar to nursing professionals is the state board of nursing. Nursing boards accomplish their mission through licensing competent and qualified individuals and then regulating licensees’ safeness and scope of practice as outlined in each state’s Nurse Practice Act.

What Are Nurse Practice Acts?

Each state has enacted important legislation known as a Nurse Practice Act. The Nurse Practice Act in each state is comprised of both statutes and administrative rules and defines the qualifications for nursing licensure as well as establishes how the practice of nursing will be regulated and monitored within that state’s jurisdiction. Nurse Practice Acts generally describe nursing scope of practice boundaries, unprofessional conduct, and disciplinary action. In most states, the Nurse Practice Act does the following:

▪ Describes how to obtain licensure and enter practice within that state.

▪ Describes how and when to renew your license.

▪ Defines the educational requirements for entry into practice.

▪ Provides definitions and scope of practice for each level of nursing practice.

▪ Describes the process by which individual members of the board of nursing are selected and describes the categories of membership.

▪ Identifies situations that are grounds for discipline or circumstances in which a nursing license can be revoked or suspended.

▪ Identifies the process for disciplinary actions, including diversionary techniques.

▪ Outlines the appeal steps if the nurse feels the disciplinary actions taken by the board of nursing are not fair or valid.

It is important to keep your state board of nursing informed of your current residence so that you receive important documents that can affect your future ability to practice in a timely fashion. Never ignore or take lightly any document received from your state board of nursing. Even if you think you have received a notice in error, contact the board of nursing immediately (Box 20.2). You also need to be informed of Nurse Practice Act requirements in a new state of residence before you begin to practice there. All Nurse Practice Acts are readily accessible online and/or easily obtained from any state board of nursing (see Appendix A on the Evolve website). If you are not familiar with the Nursing Practice Act in your state of licensure and/or state of practice, you are putting yourself and your nursing license at risk.

What Is Criminal Law?

Historically, nurses have been held accountable for their negligent conduct in civil actions and state licensing board disciplinary actions. However, negligent conduct can have criminal consequences as well. Whereas civil actions concern private interests and rights between individuals and/or businesses, criminal law involves prosecution and punishment for conduct deemed to be a crime.

Criminal negligence is based on a criminally culpable state of mind in addition to a deviation from the standard of care. The lapse in standard of care can be intentional or unintentional. For example, in November 2006, a Wisconsin nurse made an unintentional medication error that resulted in a patient’s death during childbirth. The nurse was criminally charged with patient abuse and neglect causing great bodily harm, a felony that carried a penalty of imprisonment and a significant monetary fine. The nurse eventually received probation after pleading no contest to two criminal misdemeanors. Additionally, the Wisconsin Board of Nursing suspended the nurse’s license for 9 months to be followed by a 2-year practice limitation (ASQ, 2007).

Case study 1

You are working in a hospital where a very well-known actor is admitted with a diagnosis of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia. During the patient’s stay, you are asked by a physician to administer an intravenous medication for purposes of conscious sedation to the patient while the physician performs a procedure. During the procedure, the patient has a respiratory arrest secondary to oversedation and dies. You are devastated and realize that you may have administered too much medication. You decide to confide in your best friend, who is also a nurse, about the incident. While speaking to your best friend, you mention the actor’s name and diagnosis. Your friend says that it was “illegal” for you to administer intravenous conscious sedation and expresses concern that your actions and possible medication error might land you in trouble (Critical Thinking Box 20.1).

What Is Case Law?

The role of the judiciary (court) is to apply and interpret the law. In our judicial system, two opposing parties present evidence before a judge and/or a jury who applies the law to the facts to determine the outcome of the case. When the court’s interpretation of the law leads to law itself, it is known as case law. Case law and common law are often used interchangeably to describe law that is developed by courts when deciding a case as opposed to law created through a legislative enactment or a regulation promulgated by an administrative agency. The majority of tort law is developed from case law.

Torts

Tort law, as described by Pozgar (2007), is a civil wrong committed against a person entitling the injured party to file a lawsuit to receive compensation for damages he or she suffered as a result of the alleged wrongdoing. The purpose of tort law is to determine culpability, deter future violations, and award compensation to the plaintiff if applicable. There are two categories of tort actions: unintentional and intentional. Medical negligence or professional negligence is an example of an unintentional tort and is discussed in more detail below.

What Are Intentional Torts?

Intentional torts are civil “wrongs” that are done on purpose to cause harm to another person. Instead of seeking to put the tortfeasor (the wrongdoer) in jail, however, an intentional tort claim attempts to right the wrong by compensating the plaintiff. These types of claims are less common than negligence claims, which are not purposeful acts and can be asserted against a nurse in some circumstances.

There are several types of intentional torts. Assault and battery and false imprisonment are two examples of intentional torts. Assault and battery are the legal terms that are applied to nonconsensual threat of touch (assault) or the actual touching (battery). Generally speaking, the practice of nursing involves a great deal of touching. Permission to do this touching is usually implied when the patient seeks medical care. All patients have the right, however, to withdraw their implied consent to medical care and refuse the procedure or treatment or medication being offered. A competent patient’s refusal to consent or withdrawal of consent must be respected by the health care team or there could be legal implications. For instance, the Louisiana Supreme Court awarded $25,000 to a patient’s family in a lawsuit wherein the nurses had ignored the patient’s refusal of a Foley catheter. The patient was ultimately injured in the process of removing the catheter, and the court determined that the nurses had committed battery by performing an invasive procedure against the patient’s wishes (Robertson v. Provident House, 1991). Also, a patient may wish to leave an institution “against medical advice” (AMA). If nurses use physical restraint or touching to keep this patient from leaving, these actions can lead to a civil claim of assault and battery.

False imprisonment means making someone wrongfully feel that he or she cannot leave a place. It is often associated with assault and battery claims. This can happen in a health care setting through the use of physical or chemical restraints or the threat of physical or emotional harm if a patient leaves an institution. Threats such as “If you don’t stay in your bed, I’ll have to sedate you” may constitute false imprisonment. This tort might also involve telling a patient that he or she may not leave the emergency department until the bill is paid. Another example is using restraints or threatening to use them on competent patients to make them do what you want them to do against their wishes. Unless you are very clearly protecting the safety of others, you may not restrain a competent adult (Critical Thinking Box 20.2) (Guido, 2013).

In psychiatric patient populations in which patients may pose a danger to self or others, there are many very specific state and federal laws to follow as well as institutional policies. The challenge, of course, is in preventing patients from self-harm while also maintaining the patients’ rights to liberty. This is not always an easy balance. There are many restrictions on the appropriate use of both hard and soft restraints and elevated scrutiny on their use in both hospital and long-term care facilities (Tolson & Morley, 2012). Claims of elder abuse have been filed for the misuse of restraints. You must be aware of the policies in your institution as well as any applicable statutory requirements.

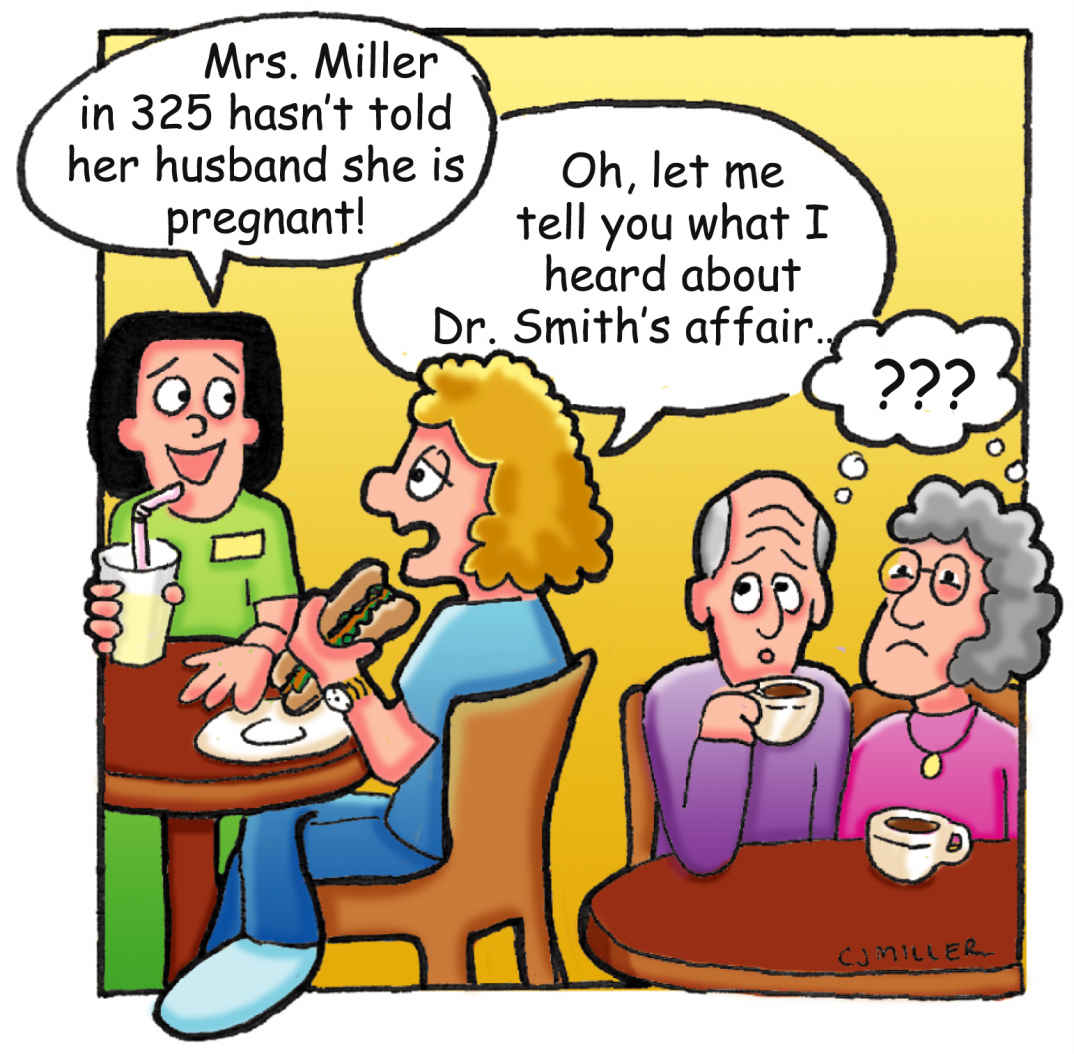

Defamation (libel and slander) refers to causing damage to someone else’s reputation. If the means of transmitting the damaging information is written, it is called libel; if it is oral or spoken, it is called slander. The damaging information must be communicated to a third person. The actions likely to result in a defamation charge are situations in which inaccurate information from the medical record is reported, such as in Case Study 1, or when speaking negatively about your co-workers (supervisors, doctors, other nurses).

Two defenses to defamation accusations are truth and privilege. If the statement is true, it is not actionable under this doctrine. However, it is often difficult to define truth, because it may be a matter of perspective. It is better to avoid that issue by not making negative statements about other people unnecessarily. An example of privilege would be required for good-faith reporting to child protective services of possible child abuse or statements made during a peer-review process. If statements made during these processes are without malice, state statutes often protect the reporter from any civil liability for defamation.

Recovery in defamation claims usually requires that the plaintiff submit proof of injury—for instance, loss of money or job. Some categories, such as fitness to practice one’s profession, do not require such proof, as they are considered sufficiently damaging without it. Comments about the quality of a nurse’s work or a health care provider’s skills in diagnosing illness would fit in this category. You can avoid this claim by steering clear of gossip and by not writing negative documents about others in the heat of the moment and without adequate facts.

Invasion of Privacy and Breaches of Privacy and Confidentiality

A good general rule involving the sharing of patient information is always to ask yourself, “Do I have the patient’s consent to share this information, or is it necessary to deliver health care services to this patient?” If the answer to either is “no,” then the information should not be communicated.

Privacy regulations under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) remain as a central focus for the public. There are specific privacy regulations under HIPAA that became effective in April 2003 and include an elaborate system for ensuring privacy for individually identifiable health information. Information used to render treatment, payment, or health care operations does not require the patient’s specific consent for its use. This includes processes such as quality assurance activities, legal activities, risk management, billing, and utilization review. However, the rules require that the disclosure be the “minimum necessary,” and a clear understanding of what information can be shared under this exception is necessary (Annas, 2003). Notice must be given to the patient regarding how the information will be used. All nurses working in health care must be aware of this law and how their institutions specifically comply with it.

Another aspect of HIPAA involves electronic information and the security measures necessary to ensure that protected patient information is not accessed by those without the right or need to know. These rules came into effect in April 2005. Each institution must have data security policies and technologies in place based on their own “risk assessment.” Many institutions require that any health information transmitted under open networks, such as the Internet, telephones, and wireless communication networks, be encrypted (coded).

Many states have physician–patient privilege laws that protect communications between physicians and their patients. This enables information to pass freely between physician and patient without concern that it will be shared with those who do not need to know it. This includes law enforcement organizations. The privilege usually extends to information about a patient in the medical record or obtained in the course of providing care. Most states extend physician–patient privilege to nurses and sometimes to other health care providers as well. This privilege generally belongs to the patient and not the health care professional, which means that only the patient can decide whether to relinquish it.

As a professional it is important to observe confidentiality when talking about patients at home and at work (Fig. 20.1). Nurses must be very careful to keep information about the patient confidential and to share information only with health care workers who must know the information to plan or to give proper care to the patient. This is sometimes difficult to do, as seen in Case Study 1.

EHRs and national clearinghouses for health information present significant confidentiality concerns. Such technologies offer many advantages, including easier and broader access to needed information and more legible documentation. These same advantages also create issues, because they make it more difficult to ensure confidentiality. Many hospitals and agencies already have policies and procedures in place, such as access codes, limited screen time, and computers placed in locations that promote privacy. The nurse is still responsible for the protection of confidentiality when computers, e-mail, voice paging systems, mobile devices, or other rapid communication techniques are used.

Privacy violations can result in a legal cause of action for the tort of invasion of privacy. This cause of action can apply to several behaviors, such as photographing a procedure and showing it without the patient’s consent, going through a patient’s belongings without consent, or talking publicly about a patient.

Miscellaneous Intentional Torts and Other Civil Rights Claims Involved With Employment

The aforementioned torts and others can be relevant to nurses in relation to their employment. These intentional torts can be brought personally against the nurse. Tortious interference with contract is a claim alleging that someone maliciously interfered with a person’s contractual (often employment) rights. This can occur, for instance, if a nurse attempts to get another nurse fired through giving false or misleading facts to a supervisor. Intentional infliction of emotional distress is described by its name, and it can also be attached to malicious acts in the employment setting. These and certain civil rights claims such as sexual harassment and discrimination are both rights and potential liabilities for every person in the work force. Although beyond the scope of this text, policies and information regarding these issues demand further investigation by each health care employee to ensure that their rights and the rights of others are not violated.

What Are Unintentional Torts?

The most common type of unintentional tort is called negligence. A person is considered to have acted negligently when he or she unintentionally causes personal injury or harm to property where the person should have acted reasonably to avoid such harm. Because professional negligence (also referred to as malpractice) can potentially affect every nurse, it is important to explore what this means. Before we delve into negligence, let’s examine classifications of legal actions and nursing licensure.

Court Actions Based on Legal Principles

There are two major classifications of legal actions that can occur as a result either of deliberate or unintentional violations of legal rules or statutes. In the first category are criminal actions. These occur when you have done something that is considered harmful to society as a whole. The trial will involve a prosecuting attorney, who represents the interests of the state or the United States (the public), and a defense attorney, who represents the interests of the person accused of a crime (defendant). These actions can usually be identified by their title, which will read “State v. [the name of the defendant]” or “U.S. v. Smith [the name of the defendant].” Examples include murder, theft, drug violations, and some violations of the Nursing Practice Acts, such as misuse of narcotics. Serious crimes that can cause the perpetrator to be imprisoned are called felonies. Less serious crimes typically resulting in fines are misdemeanors. The victim, if there is one, may or may not be involved in a decision to prosecute a case and is considered only a witness in the criminal trial. Laws differ in states as to victim rights and/or if the person or the state will receive any of the money from fines. In Case Study 1, your actions would not likely result in a criminal action. Recently, however, there have been instances in which a nurse was thought to have recklessly caused a patient’s death, and a case was brought in criminal court for negligent homicide. The issues involved in such criminal actions will be discussed later in this chapter.

The second category of legal claims includes civil actions. These actions concern private interests and rights between the individuals involved in the cases. Private attorneys handle these claims, and the remedy is usually some type of compensation that attempts to restore injured parties to their earlier positions. Examples of civil actions include malpractice, negligence, and informed consent issues. The victim (patient) or victim’s family (patient’s family) brings the lawsuit as the plaintiff against the defendant, who may be the individual (nurse) or company (hospital) that is believed to have caused harm. In the situation presented, you might be sued for malpractice by the actor’s spouse if it is felt that you acted below a standard of care and caused the actor’s death.

Sometimes an event can include both criminal and civil consequences. When that happens, two trials are held with different goals. The amount of evidence required to support a guilty verdict is different for each type of trial. The criminal case requires that the evidence show that the defendant was guilty beyond a shadow of a doubt. The civil case requires only that the evidence show that the defendant was more likely guilty than not guilty. This is what makes it possible for someone such as O. J. Simpson to be found “not guilty” in a criminal trial but “guilty” or negligent in a civil trial.

Nursing Licensure

All states prohibit the practice of nursing without a license. Many other professional occupations require a license. Have you ever asked yourself what is the purpose of licensure and why some occupations require a license while others do not? When specialized knowledge and skill are required to perform often complex professional activities, particularly activities involving potential harm to the public, licensure is usually required. Licensure protects the public health and welfare by establishing entry-level qualifications and ongoing competencies to maintain and ensure safe practice.

A license to practice nursing is a privilege, not a right. According to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN, 2011a), licensure is “the process by which boards of nursing grant permission to an individual to engage in nursing practice after determining that the applicant has attained the competency necessary to perform a unique scope of practice.” Each state Board of Nursing follows licensing statutes and rules designed to determine if potential applicants possess the competency and necessary skills to practice safely in their chosen field.

Even the successful completion of an educational program in nursing and/or passing the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN®) does not guarantee that a state board of nursing will grant you a license to practice nursing. A license is granted by a state after a candidate has successfully met all the requirements in that particular state. Examples of these requirements may include criminal background checks and successful completion of a board-approved nursing education program.

When you graduate from nursing school and successfully complete the state licensing process to become a practical or registered nurse, you achieve professional licensure status under the law. Having a license to practice nursing brings you into close contact with laws and government agencies. Professional licensure is governed by Nurse Practice Acts that you must follow in the state(s) in which you are licensed and/or practicing nursing. Once you are licensed, the state continues to monitor your practice and has the authority to investigate complaints against your license. If you are found to have violated the Nurse Practice Act, a state board of nursing can take disciplinary action against your license.

Disciplinary Actions

Several levels of disciplinary actions can occur based on the severity of the practice act violation and the ongoing risk to the public. For instance, state boards of nursing have disciplinary power ranging from censure to probation, suspension, revocation, and denial of licensure. One of the most common reasons for state board action against nurses involves substance abuse and the diversion of prescription medications for personal use (Brent, 2001). Boards of nursing are increasingly concerned about this issue, because it has significant impact on rendering safe, effective patient care (NCSBN, 2014).

Final disciplinary actions are a matter of public record and can be accessed by contacting a state board of nursing. Additionally, final disciplinary actions are reported to governmental and nongovernmental authorities for public protection. For example, NURSYS is a nongovernmental electronic information system that includes the collection and warehousing of nurse licensing information and disciplinary actions. The Healthcare Integrity and Protection Data Bank (HIPDB) and the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) are two federal data banks of information about health care providers in the United States. Adverse actions taken against a health care professional’s license are required by federal law to be reported to the HIPDB and NPDB. However, the general public may not access information included in the NPDB and HIPDB, as the information is limited by law to entities such as hospitals and health plans and government agencies.

Scope of Practice

The scope of practice for professional nursing is the range of permissible activity as defined by the law; in essence it defines what nurses can and, sometimes more important, what nurses cannot do. Because the scope of nursing practice is defined by state legislation, there is great variation from state to state both in specificity and in the range of activities that are legally authorized. Many state legislatures have enacted very specific scope of practice statements whereas others have drafted very vague and broad scope of practice statements and have left the job of describing the specific activities to the state board of nursing. Some state scope of practice statements are very restrictive, whereas others allow a much broader range of activities. It is very important that a nurse become very familiar with the practice act and the scope of practice as defined by the legislature or the state board of nursing in the state where he or she intends to practice.

There is significant variability for the scope of practice of licensed practical or vocational nurses (LPN/LVN) and even more variability for the scope of practice for advanced practice nurses (nurse practitioners, midwives, anesthetists, collectively called APRN) (NPDB, 2010). Because of the restrictive nature of the scope of practice statements of many states, all APRNs are not able to practice to the full extent of their education and training.

Case study 2

After your incident with the actor, you decide to leave the state. You have to answer detailed questions on your licensure application for the new state about any previous malpractice claims. You had heard something about a claim being filed against your former hospital but had left shortly after that. Now you have received a notice from the state board of nursing of your previous residence inquiring about the incident with the actor and asking for a response within 2 weeks. The letter has taken a long time to be forwarded to you, and the 2-week deadline has passed. What should you do?

Multistate Licensure

The Nurse Licensure Compact is a “mutual recognition agreement” between states that have adopted the Compact legislation. The Nurse Licensure Compact allows both registered and practical nurses with a license in good standing in their “home state” to practice nursing in any of the other Compact states (“member states”) without going through the process of obtaining additional licensure. According to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), 25 states have enacted the Nurse Licensure Compact (NCSBN, 2015).

A Compact license is also known as a “multistate license.” It is important to note that only nurses who declare a Compact state as their primary state of residence are eligible for a multistate license. This means that if you obtain a license in state that is not participating in the Nurse Licensure Compact, you do not have a multistate license and cannot practice nursing outside of your primary state of residency without obtaining additional licensure in a new state. It is also very important to note that when you permanently relocate to another Compact or non-Compact state, all licensure laws including the Nurse Licensure Compact require you to obtain licensure in the new state.

The APRN Compact, approved by the NCSBN on May 4, 2015, allows an advanced practice registered nurse to hold one multistate license with a privilege to practice in other Compact states. The APRN Compact is under consideration in several states.

What about Substance use Disorder in Nursing?

Substance use disorder describes a pattern of substance use behavior that encompasses substance misuse to dependency or addiction. Substances can be alcohol, legal (prescription) drugs or illegal drugs. Substance use disorder can affect nurses and anyone regardless of their age, gender, or economic circumstances. It is a progressive and sometimes fatal disease but also one that can be treated. Boards of nursing are increasingly concerned about this issue, because it has significant impact on rendering safe, effective patient care.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) estimated that 6% to 8% of nurses abuse drugs or alcohol at a level sufficient to impair their professional judgment (NCSBN, 2011b). Many nurse practice acts have mandatory reporting obligations regarding impairment. Allowing an impaired nurse to practice not only puts the nurse and the patient at risk but also negatively impacts the facility’s reputation and the nursing profession as a whole. It is important that you know what the reporting requirements are for your state board of nursing and your facility.

One of the most common reasons for state board action against nurses involves the diversion of prescription medications for personal use (Brent, 2001). Do not ever assume that you or your colleagues are immune from substance misuse, abuse, or addiction. High stress and easy access to drugs contribute to the problem for health care providers. A slippery slope occurs when a nurse first takes any medication—even an aspirin—that does not belong to him or her.

If you do find yourself in trouble with drugs or alcohol, it is advisable to voluntarily report your substance misuse or abuse to your state board of nursing and seek immediate treatment. The boards of nursing in 41 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands have alternative monitoring programs to assist nurses with substance use disorders, which may prevent their licenses from being suspended or revoked. The nondisciplinary rehabilitative approach to substance use disorders recognizes the importance of returning a sober abstinent nurse to the work force (NCSBN, 2011b).

States with alternative monitoring programs allow enrolled nurses to meet specific behavioral criteria, such as blood or urine testing, ordered evaluations, and attendance at rehabilitation programs, either while disciplinary action is being undertaken or instead of bringing formal disciplinary proceedings. The primary concern is to ensure safe nursing practice. If a nurse is involved in a voluntary rehabilitation program through a contract with a state board and suffers a relapse or has additional problems, the board may bring formal disciplinary action against the nurse that may negatively affect licensure for the rest of his or her life.

Negligence

Case study 3

You are a nurse working in a hospital. The physician tells you that you need to administer an injection of Vistaril (hydroxyzine pamoate). You make sure that the order is documented in the medical record. The medication comes up from the pharmacy, and you check it against the physician’s order and find that it is correct. You walk into the patient’s room and use at least two patient identifiers to make sure you have the right patient. You give the injection in the patient’s right dorsogluteal muscle and document this in the medical record.

The patient leaves the hospital. A year later, you are told that a lawsuit has been filed against the hospital by the patient. It seems the patient is claiming that the injection you gave him caused sciatic nerve damage and his whole leg is numb (Critical Thinking Box 20.3).

Many times nurses worry about being sued for something when, in the eyes of the law, no negligence has occurred. Not all poor outcomes are a result of negligence or are a violation of the Nurse Practice Act. A nurse also may legitimately make an error in judgment. Therefore, it is important for a nurse to know the basic elements that must be proved before negligence can occur. Then the nurse can evaluate incidents realistically.

Basic Elements of Negligence

There are four basic elements of negligence, all of which must be proven by the plaintiff in a negligence lawsuit in order for the plaintiff to be awarded compensation.

The job of the patient’s (plaintiff’s) attorney is to prove to a jury that each element of negligence has occurred. This is not always a simple straightforward process, and it can be frustrating and confusing for all involved parties. It is important for the nurse to understand the elements of negligence and how each element may be proved in a court of law.

Do You Have a Professional Duty?

Generally speaking, all persons owe a duty of “due care” to others in our daily activities and lives. This means that you must conduct yourself in a reasonable and prudent manner to avoid causing harm to another person or his or her property. The duty of due care also applies to nursing professionals who have a professional duty to act as a reasonable nurse would act in the same or similar circumstances to avoid causing foreseeable harm to patients.

To prevail in a negligence action, the plaintiff must establish that there was a nurse–patient relationship in which a professional duty was owed by the nurse to the patient. If you are working as a nurse in a hospital, the nurse–patient relationship is usually implied and you owe a professional duty of care to your patients. What if you are giving advice in your home informally to a friend, relative, or neighbor? In this setting, it may not be implied that you are acting as a nurse, particularly in the absence of payment, institution, or formal contract.

What if you stop at an accident to assist someone who is injured? Good Samaritan statutes provide immunity from malpractice to those professionals who attempt to give assistance at the scene of an accident. In essence, you do not have any professional duty to stop, although you may feel an ethical duty to do so. However, a nurse may be sued in some states for rendering Good Samaritan aid if the nurse is found to have acted in a grossly negligent manner. If you do stop at the scene of an accident to provide aid, know that in most—if not all—states you cannot be sued for malpractice for what you might or might not do, unless the aid you provide is grossly negligent. That is, you do not have a professional standard of care to adhere to unless you are a professional at the scene as part of your employment. All persons, of course, are expected not to leave a victim in a position that is more dangerous than when found. After you stop to help the injured person, stay with him or her until you are given clearance by emergency responders.

Sometimes nurses volunteer to provide nursing assistance at sporting events or other activities where it is foreseen that professional services may be needed. In thinking about this, you may see that such a situation is not quite as clear as other situations. If you are at a first-aid station or if you are wearing a badge indicating you are a nurse, then you have the appearance of a professional, and people may rely on that appearance when seeking advice or assistance.

Falling Below the Standard of Care: Was There a Breach of the Professional Duty?

After establishing that a professional duty is owed, the question becomes, “What is that duty?” The duty owed by a nurse to a patient is different from the duty owed to the patient by another health care discipline such as a physician or physical therapist. The duty of a nurse will be to act as a reasonable nurse would act under the same or similar circumstances. This is known as the standard of care and is a very important factor in most negligence cases. You may be asking yourself, “How will my attorney prove that I acted as a reasonable nurse and within the standard of care?”

The following aspects may be considered when attempting to establish through evidence what the standard of care for the nurse might be.

What About the Nurse Practice Act?

Perhaps the most important guideline for nurses will be the Nurse Practice Act in the state in which you are practicing. Most acts describe in fairly general terms what a nurse may or may not do. Prohibitions, or things that are considered to be unprofessional conduct, are usually more specific. A Nurse Practice Act violation means that you have fallen below a standard of care set by the state for nurses. It also may mean that you risk an action against your license. If you do not know what these prohibitions are, you are putting yourself in jeopardy. As stated previously, and as applied here to the standard of care, it is important that you obtain a copy of the Nurse Practice Act for the state(s) in which you are or will be licensed to practice, and be sure to stay current with your licensing standards. For instance, Texas now requires that all applicants for licensure pass a nursing jurisprudence examination, which is based on the Texas Nursing Practice Act and the Texas Board of Nursing Rules and Regulations (Texas BON, 2010).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree