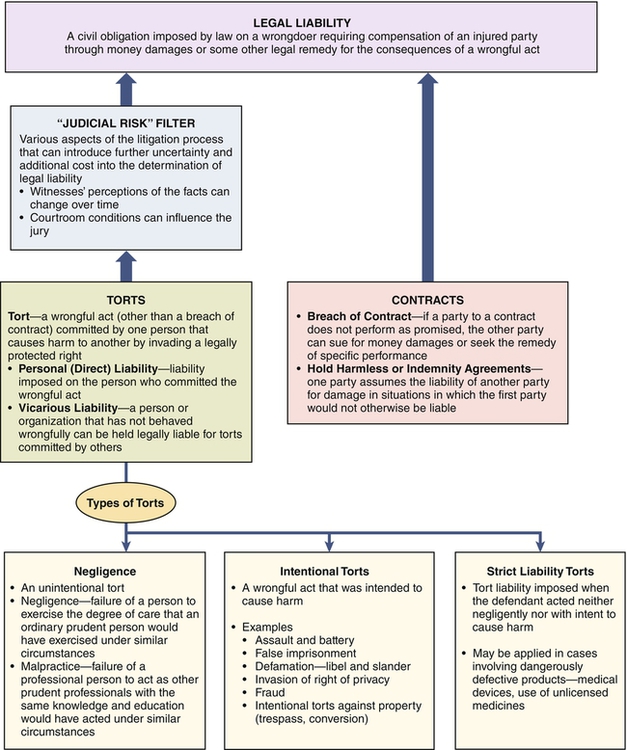

Autonomy involves accountability, as well as authority, for one’s decisions and actions. As professional autonomy and responsibility increase, so does the level of accountability and liability. To the extent that nurses are subject to malpractice lawsuits and carry malpractice insurance, nurses are held accountable (Aiken, 2004). Nurse managers use their autonomy to make decisions about practice situations. They are accountable for carrying out supervisory responsibilities; proper notification; assessing the competency of staff; training, orientation, and evaluation of staff; reasonable staffing decisions; and monitoring and maintenance of professional treatment relationships with clients, called nonabandonment (Aiken, 2004; Guido, 2010). Nurses, nurse managers, and health care facilities are all subject to being found legally liable (i.e., legally responsible) for harm caused to others by civil wrongs. More specifically, liability is created when the law imposes a civil obligation on a wrongdoer to compensate an injured party for the consequences of a wrongful act. As shown in Figure 6-1, there are two sources of legal liability—torts and contracts. As indicated in Figure 6-1, determination of legal liability as a result of a tort depends on more than just the various technical elements of the tort that must be proved by the injured party (plaintiff), the presentation of various available defenses by the defendant, and the formal rules of the judicial system regarding the litigation process. In the case of torts, the legal outcomes are often influenced also by what may be termed judicial risk—various aspects of the litigation process that can introduce further uncertainty and additional cost into the determination of legal liability. Judicial risk can result in findings with respect to legal liability that are not based solely on the merits of the case nor on the rules of law applicable to the case. There are three categories of torts: negligence, intentional torts, and strict liability torts. Negligence is the failure to exercise the proper degree of care required by the circumstances. In general, the standard of care is defined as that which a reasonably prudent person would exercise under the circumstances to avoid harming others. Malpractice is a special type of negligence that applies only to professionals and employs a higher standard of care than ordinary negligence (Weld & Bibb, 2009). Malpractice is the failure of a professional person to act as other prudent professionals with the same knowledge and education would act under similar circumstances. Depending on the nature of the situation involved, nurses and nurse leaders may be subject to either ordinary negligence or malpractice. An example of ordinary negligence would be a situation in which a nurse saw that food had been spilled on a client’s floor but failed to have it cleaned up, and as a result, the client slipped and broke her hip. Because this is an act not requiring the exercise of professional judgment, the standard of care in determining negligence would be the degree of care that an ordinary prudent person would exercise under the circumstances. However, if the client had fallen and broken her hip because a nurse had failed to raise the side rails on the client’s bed, the standard of care in determining malpractice would be the degree of care other prudent professionals with the same knowledge and education could be expected to exercise under similar circumstances. As shown in Figure 6-1, contracts are also a source of legal liability. In most states, employment of nurses generally follows the employment-at-will doctrine in which there is no written contract specifying the term of employment. However, in some cases, nurse managers, especially those at higher levels in an organization, negotiate written employment contracts. In addition, a few courts have ruled that contracts existed on the basis of language used in advertisements and statements made during the interviewing process. Courts also have held that contracts may arise after employment based on statements made in employee manuals and handbooks. With an increasing number of nurses negotiating various types of consulting arrangements with facilities, working as independent contractors and operating their own privately owned businesses, contracts are playing an even greater role in nursing. Activities of clinical client care involve corresponding legal accountability and risk. Errors do happen. Some lead to injury to a client. At minimum, nurses have an ethical obligation to nonmaleficence, or to do no harm to clients. This duty is discharged in part by remaining competent in knowledge and skills and the standards of practice. Nursing negligence/malpractice occurs when the nurse’s actions are unreasonable given the circumstances or fail to meet the standard of care or when the nurse fails to act and causes harm. In nursing, harm related to clinical practice commonly arises from negligent acts or omissions (unintentional torts) and a variety of intentional acts (intentional torts) such as invasion of privacy or assault and battery (Aiken, 2004). 1. A duty of care was owed to the injured party. 2. There was a breach of that duty. 3. The breach of the duty caused the injury (causation). Critical in determining liability for malpractice (professional negligence) is the definition of the duty (standard) of care owed by the nursing professional to the client. The standard of care, the minimum requirements that define an acceptable level of care, is “the average degree of skill, care, and diligence exercised by members of the same profession under the same or similar circumstances” (Aiken, 2004, p. 39). Standards of care can be found in the state nurse practice act, standards published by the American Nurses Association, other professional organizations and specialty practice groups, federal agency guidelines and regulations, and the facility’s policy and procedure manuals. In malpractice cases, the standard of care owed to the injured client is commonly introduced into evidence by expert witnesses and the impact of that evidence is ultimately determined by the jury after receiving instructions from the judge on the law applicable to its use. Common clinical practice areas that give rise to allegations of malpractice include the general areas of treatment, communication, medication, and the broad category of monitoring/observing/supervising/surveillance. Examples of common negligence allegations in nursing malpractice suits include patient falls, use of restraints, medication errors, burns, equipment injuries, retained foreign objects, failure to monitor, failure to ensure safety, failure to take appropriate nursing action, failure to confirm accuracy of physicians’ orders, improper technique or performance of treatments, failure to respond to a patient, failure to follow hospital procedure, and failure to supervise treatment (Aiken, 2004; Weld & Bibb, 2009). Over and above personal liability for clinical practice, nurses and nurse managers have accountability and liability for their acts of delegation and supervision. Both nurses and nurse managers are obligated to report incompetent practice that occurs at any point in the care delivery process. Nurse managers have a duty to train, orient, and evaluate the ability of nursing staff to perform specific functions and tasks. Health care organizations have a duty to monitor the competence and ability of nursing and medical professionals and to inquire about their credentials (Aiken, 2004). Under the doctrine of respondeat superior (meaning “let the master answer”), an employer may be held vicariously liable for the negligent act or omission of an employee. For the employer to be found vicariously liable, the employee’s act or omission must occur both during the course of employment and while the employee was acting within the scope of employment. For example, if a nurse negligently injured a client during the course of and within the scope of employment, not only would the nurse be directly liable for damages but also the health care organization would be vicariously liable. Because of their “deep pockets” (their ability to pay larger settlements or judgments) and the concept of vicarious liability, health care facilities are almost always named as defendants in malpractice suits. Nurse managers can play a key role in assisting facilities to avoid payments for vicarious liability by ensuring that the nurses they supervise deliver competent care to clients while following facility policies and procedures (Guido, 2010). Under the doctrine of ostensible authority (or apparent agency), facilities may also become liable for the negligence of an independent contractor if it would appear to a reasonable client that the independent contractor is a facility employee. For example, a hospital might be held liable for the negligence of an agency nurse who appeared to a client to be a nurse employed by the hospital. Guido (2010) recommends that when dealing with agency or temporary personnel, nurse managers should, among other things, do the following: • Consider their skills, competencies, and knowledge when delegating tasks and supervising their actions. • Ensure that they are made aware of facility policies and procedures, resource materials, and documentation procedures. • Assign a resource person to each temporary staff member to serve in the role of mentor and help prevent potential problems from occurring because of a lack of familiarity with institution routine or where to turn for assistance. Under the doctrine of corporate liability, health care organizations themselves are held legally responsible for “ensuring that competent and qualified practitioners deliver quality health care to consumers” (Guido, 2010, p. 307). Under this doctrine, facilities can be held liable for a variety of activities that are beyond the control of any single employee, including the following (Aiken, 2004): • Failure to check references, educational credentials, license status, disciplinary actions, and criminal record for applicants • Failure to protect the clients from health care providers who can cause harm • Failure to monitor the quality of care provided by all medical and nursing personnel within the facility • Failure to periodically review staff competency • Failure to terminate an employee who has harmed a client and then injures another client Nurse managers can help the facility avoid corporate liability by, among other things, ensuring that those who report to them remain competent and qualified and have current licensure. Nurse managers should also report to appropriate managers dangerously low staffing levels or incorrect mixes of staff for effectively meeting the health care needs of clients, as well as report incompetent, illegal, or unethical practices to appropriate authorities (Guido, 2010). In addition to facility liability arising from vicarious liability, the doctrine of ostensible authority, and the doctrine of corporate liability, health care organizations are constrained by specific laws related to employment issues. Although the various health care providers and their employing organizations have specific legal and ethical obligations to clients, such as executing informed consent and following the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990, organizations carry specific legal and ethical obligations toward employees. The employer has an obligation to provide a safe and secure care delivery environment (Aiken, 2004). Management policies and procedures must be in compliance in the areas of hiring, performance appraisal, management of employees with problems, and termination (Aiken, 2004). Lawsuits also have formed the basis for the standards to be met for the termination of employees. Discharges may occur for lack of adherence to employer-established policies or standards, “good cause” per institutional policy, illegal activity, assault, insubordination, or excessive absenteeism. Written notice and the reasons for termination avoid misunderstandings and show justice through due-process procedures. Careful documentation is important. If the employee is a member of a protected group, the employer may be required to submit formal justification for the termination (Aiken, 2004). Clearly, nurses, nurse managers, and the facilities that employ them face legal liability from a wide array of sources. Although it is not possible to avoid legal liability in all cases, nurse managers can take a number of steps to protect themselves, staff nurses reporting to them, and their facilities where possible. The first step is summed up in a statement often attributed to football coach Vince Lombardi: The best defense is a good offense. Nurse managers can do a number of things in applying this strategy of using a good offense to defend against problems leading to legal liability. First, because problems generally can be dealt with more effectively if anticipated, nurse managers should see that both they and the staff nurses who report to them are knowledgeable concerning the most common problem areas related to malpractice and the other sources of legal liability, especially new ones that have not yet been experienced within the unit. Likewise, nurse managers should ensure that both they and their staff nurses are aware of the many prevention activities that can aid them in avoiding these legal liability problems. Providing this information to staff nurses and using examples will probably improve both recognition and retention. In addition to the previous brief discussion of the sources of legal liability faced by nurses and nurse managers and the activities for preventing them, extensive information, including examples, is available from numerous sources. These include books (e.g., Aiken, 2004; Brothers, 2005; Guido, 2010), articles in nursing journals (e.g., Austin, 2011; Frank-Stromborg & Christensen, 2001a, b; Miller & Glusko, 2003), and a variety of websites that present articles and continuing education materials about recommendations for avoiding malpractice (e.g., Croke, 2003; Nurses Service Organization [NSO], 2012; Wetter, 2007). • Any client can sue a staff nurse, nurse manager, and/or health care facility for a tort, and if no response is filed within the legal time frame, the court will enter a default judgment against the defendant. Thus, at a minimum, regardless of the apparent validity of the grounds for the lawsuit, the defendant must incur defense costs or lose. • Given the typical lengthy period between the defendant’s act or omission and the introduction of evidence into the trial, many things can happen that will alter the perception of the facts. Witnesses, for example, may be questioned repeatedly, coached, or simply forget exactly what they witnessed. • Conditions in the courtroom can also influence the jury. Some jury members may be influenced by the dress or behavior of the defendant’s attorney and form subsequent opinions despite the facts (e.g., a high-priced lawyer with an arrogant attitude may elicit feelings such as “We’ll show him”). Or the appearance of the plaintiff may influence jurors (e.g., “How could a little old man like that be partly responsible for his own injuries, and besides, who cares anyway since the defendant has liability insurance?”). • Often more than one principle of law applies to a case, and the outcome may be influenced by which one the judge uses in giving his or her instructions to the jury. • In suits such as those alleging malpractice in providing or failing to provide proper end-of-life care, juries and even judges can be sufficiently influenced by their emotions so as to rationalize a finding of legal liability against the defendant, especially when, as is generally the case, liability insurance is available to pay the judgment. In fact, in some cases, a jury can actually change the law of a jurisdiction in making its decision. (See Case Study.)

Legal and Ethical Issues

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

LEGAL ASPECTS

DEFINITIONS

LAW AND THE NURSE MANAGER

Personal Negligence in Clinical Practice

Liability for Delegation and Supervision

Liability of Health Care Organizations

LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Legal and Ethical Issues

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access