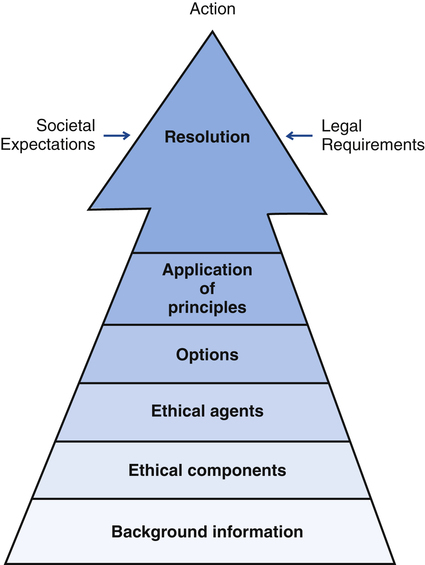

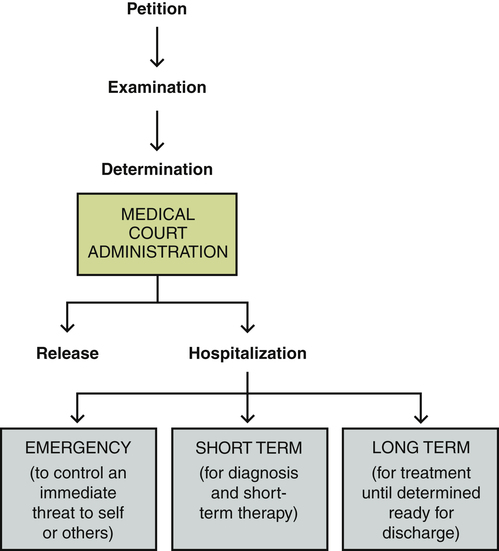

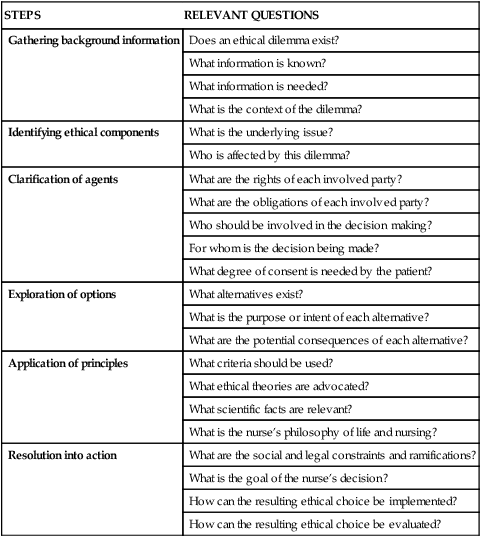

1. Describe ethical standards, decision making, and dilemmas impacting psychiatric nursing practice. 2. Compare and contrast the two types of admission to a psychiatric hospital and the ethical issues raised by commitment. 3. Examine involuntary community treatment and its implications for improving the care received by psychiatric patients. 4. Analyze the common personal and civil rights retained by psychiatric patients and ethical issues related to them. 5. Discuss the insanity defense and the psychiatric criteria used in the United States to determine criminal responsibility. 6. Evaluate the rights, responsibilities, and potential conflict of interest that arise from the three legal roles of the psychiatric nurse. Psychiatric nurses may encounter complex ethical situations in caring for patients and families with mental illness. As professionals they are held to the highest standards of ethical accountability in their clinical practice (Murray, 2007). A number of essential ethics skills are listed in Box 8-1. These allow the nurse to provide care that is socially responsible and personally accountable. Ethical decision making involves trying to distinguish right from wrong in situations without clear guidelines. A decision-making model can help identify factors and principles that affect a decision. A model for critical ethical analysis that describes steps or factors that the nurse should consider in resolving an ethical dilemma is shown in Figure 8-1. 1. The first step is gathering background information to obtain a clear picture of the problem. This includes finding available information to clarify the underlying issues. 2. The next step is identifying the ethical components or the nature of the dilemma, such as freedom versus coercion or treating versus accepting the right to refuse treatment. 3. The third step is the clarification of the rights and responsibilities of all ethical agents, or those involved in the decision making. This can include the patient, the nurse, and possibly many others, including the patient’s family, physician, health care institution, clergy, social worker, and perhaps even the courts. Those involved may not agree on how to handle the situation, but their rights and duties can be clarified. 4. All possible options must then be explored in light of everyone’s responsibilities, as well as the purpose and potential result of each option. This step eliminates alternatives that violate rights or seem harmful. 5. The nurse then engages in the application of principles, which stem from the nurse’s philosophy of life and nursing, scientific knowledge, and ethical theory. Ethical theories suggest ways to structure ethical dilemmas and judge potential solutions. Four possible approaches include the following: a. Utilitarianism, which focuses on the consequences of actions. It seeks the greatest amount of happiness or the least amount of harm for the greatest number, or “the greatest good for the greatest number.” b. Egoism is a position in which the individual seeks the solution that is best personally. Oneself is most important, and others are secondary. c. Formalism considers the nature of the act itself and the principles involved. It involves the universal application of a basic rule, such as “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” d. Fairness is based on the concept of justice, and benefit to the least advantaged in society becomes the norm for decision making. 6. The final step is resolution into action. Within the context of social expectations and legal requirements, the nurse decides on the goals and methods of implementation. Table 8-1 summarizes these steps and suggests questions nurses can ask themselves in making complex ethical choices in psychiatric nursing practice. TABLE 8-1 STEPS AND QUESTIONS IN ETHICAL DECISION MAKING An ethical dilemma exists when moral claims conflict with one another. It can be defined as follows: As tests for genes become more easily available, pressures will grow for prenatal testing, screening of children and adults, selection of potential adoptees, and premarital screening. Ethical issues here will relate to knowledge about genetics, the impact of this information on one’s sense of self, the boundaries of personal choice, as well as the potential discriminatory use of genetic information to deny people access to insurance and employment (Cheung, 2009; Appelbaum, 2010). Hospitalization can be either traumatic or supportive for the patient, depending on the institution, attitude of family and friends, response of the staff, and type of admission (Newton-Howes and Mullen, 2011; Sheehan and Burns, 2011). The two major types of admission are voluntary and involuntary. Table 8-2 summarizes their distinct characteristics. TABLE 8-2 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TWO TYPES OF ADMISSION TO PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALS • Medical certification means that physicians make the decision. • Court or judicial commitment is made by a judge or jury in a formal hearing. • Administrative commitment is determined by a special tribunal of hearing officers. If treatment is necessary, the person is hospitalized. The length of hospital stay varies depending on the patient’s needs. Figure 8-2 presents a clinical algorithm of the involuntary commitment process. It identifies three types of involuntary hospitalization: emergency, short term, and long term. Most mentally ill people are not dangerous to themselves or others. Studies show that the vast majority of people with serious mental illness, particularly women, are not violent, but rather are often the victims of violence. Research does suggest, however, that a subgroup of people with mental illness may be more dangerous and that they share sociodemographic features of violent offenders in the general population, including poverty (Elbogen and Johnson, 2009). Patients in this subgroup have one or more of the following: • Noncompliance with medications • Antisocial personality disorder • Lack of perceived need for treatment These characteristics can serve as predictors of potential violence. It is important that patients with severe psychiatric disorders be identified and appropriately treated. It also should be remembered that violent behavior by people with serious mental illness is only one part of a larger problem: the failure of public psychiatric services and the lack of adequate community support for the mentally ill (Chapter 34). This has resulted in large numbers of mentally ill people among the homeless, a large number of mentally ill people in jails and prisons, and a revolving door of psychiatric readmissions. This raises questions regarding the sociocultural context of psychiatric care (Chapter 7) and the role of mental health professionals as enforcers of social rules and norms. Thus the behavioral standard of dangerousness can change the function of the psychiatric hospital from a place of therapy for mental illness to a place of confinement for offensive behavior. Research has shown that discharge AMA was most commonly predicted by patient factors such as young age, single marital status, male gender, co-morbid diagnosis of personality or substance use disorders, disruptive behavior, and history of many hospitalizations ending AMA. Provider variables included failure to orient patients to hospitalization and failure to establish therapeutic provider-patient relationships. Clinical outcomes included reduced benefit from treatment; poorer psychiatric, medical, psychosocial, and socioeconomic functioning; overused emergency care; underused outpatient services; and more frequent rehospitalizations (Brook et al, 2006). Documentation of AMA patient requests should include the following: • The mental status of the patient • The patient’s own description of why he wants to leave • Content of discussions in which possible risks of leaving were described • Instructions on medications and follow-up care • Conversations with significant others who may have been present

Legal and Ethical Context of Psychiatric Nursing Care

Ethical Standards

Ethical Decision Making

STEPS

RELEVANT QUESTIONS

Gathering background information

Does an ethical dilemma exist?

What information is known?

What information is needed?

What is the context of the dilemma?

Identifying ethical components

What is the underlying issue?

Who is affected by this dilemma?

Clarification of agents

What are the rights of each involved party?

What are the obligations of each involved party?

Who should be involved in the decision making?

For whom is the decision being made?

What degree of consent is needed by the patient?

Exploration of options

What alternatives exist?

What is the purpose or intent of each alternative?

What are the potential consequences of each alternative?

Application of principles

What criteria should be used?

What ethical theories are advocated?

What scientific facts are relevant?

What is the nurse’s philosophy of life and nursing?

Resolution into action

What are the social and legal constraints and ramifications?

What is the goal of the nurse’s decision?

How can the resulting ethical choice be implemented?

How can the resulting ethical choice be evaluated?

Ethical Dilemmas

Hospitalizing the Patient

VOLUNTARY ADMISSION

INVOLUNTARY ADMISSION

Admission

Written application by patient

Application did not originate with patient

Discharge

Initiated by patient

Initiated by hospital or court but not by

patient

Civil rights

Retained fully by patient

Patient may retain none, some, or all,

depending on state law

Justification

Voluntarily seeks help

Mentally ill and one or more of following:

Dangerous to self or others

Need for treatment

Unable to meet own basic needs

Involuntary Admission (Commitment)

The Commitment Process.

Commitment Dilemma.

Dangerousness

Discharge

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access