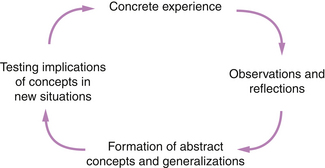

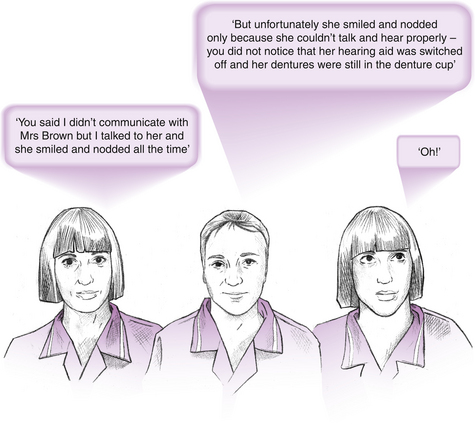

Chapter 9 There are some who see the initial preparation of health care practitioners as providing would-be professionals with a set of prescribed theory, rules, routines and behaviours in a pre-packaged and pre-determined curriculum. The argument for preparing practitioners in this manner is that it reduces the risks of professionals failing to provide a reliable service. This so called ‘technical–rational’ view of professionalism has received much criticism from writers such as Schön (1987, 1983) who stated that such simple offerings do not prepare practitioners to meet the real situations of practice, as this model makes assumptions that practice is a relatively simple interaction in which the practitioner gives and patients and clients receive. Schön emphasized that practice is messy, unpredictable, unexpected and requires the ability to improvise – this ability is often diminished by training and routines. One important ‘hallmark’ of the health care professional is generally acknowledged to be the need to be aware of, and to deal with, complex human issues as part of practice (Fish & Twinn 1997). These essential human interactions between professionals and patients/clients make the detailed knowledge and skills needed in each interaction unpredictable. Fish & Twinn (1997:38-39) take this point further: A professional needs to be able to exercise professional judgement and select or even create knowledge necessary to the unique situation. Practitioners need to be prepared so that they are able to engage in these processes not only through their initial pre-registration preparation but also through continuing post-registration education. The technical–rational model of professional preparation, and its consequent influences on how the practitioner practises, does not equip the practitioner fully to deal with what Schön (1983:3) termed the ‘swampy lowlands’ of practice – those aspects of professional work that cause the greatest human concern and yet defy the use and application of rules and routines. Furthermore, professional knowledge and practices change constantly; this requires the practitioner to be motivated in order to refine and update knowledge and practices so that professional expertise and thus ‘practice wisdom’ (Hull 1998) is continually developing. What is therefore also needed is a model for preparing for professional practice that does not rely slavishly on the use and application of rules, schedules and prescriptions. 1. The preparatory phase. The preparatory phase focuses on: 2. The experiencing phase. During this phase the student ‘reflects-in-action’. Several teaching/learning strategies will assist and influence how the learner engages with, and reflects during, the experience: 3. The processing phase. The experience is systematically reflected on during this phase. There are three key stages in reflecting on experience: In 1926, Lindeman made the point that experience is the richest resource for adults’ learning and put forward the case for the core methodology of adult education to be the analysis of experience. Despite Lindeman’s counsel, the dismal picture was that more than half a century later student nurses were still learning clinical practice ‘by doing’ only (Alexander 1982a, b). A study by Phillips et al (2000) suggests that the ‘analysis of experience’ called for by Lindeman in 1926 is still predominantly absent in the learning of student nurses and student midwives during their clinical placements. Work on experience-based learning (Boud et al 1993, Boud & Walker 1990, Kolb 1984, Dewey 1938) tells us that learning from clinical experience is not the simple ‘learning by doing’ as has been accepted for too long. What students do, see, hear and smell during clinical placements can often remain at a superficial level unless they are stimulated to analyse critically their observations and to question the meaning of their experiences and their implications for future learning. They also need to be stimulated to apply theory to practice. Thirty years ago, Alexander (1982a,b) made it clear that student nurses need help in learning how to learn from their everyday work with patients, to apply theory to practice and to use facts learned in the classroom in a variety of clinical experiences with individual patients. The implications of all this for the education of health care professionals is that students need to learn to relate theoretical material to a variety of clinical problems from the earliest days of training. For students, learning during clinical practice is a complex activity. The student has to contend and learn to deal with the complex, unstable and uncertain worlds of practice (Schön 1987). At the same time, the student needs to be able to synthesize theoretical content from various fields, become familiar with the patients/clients and their needs and problems, learn to analyse those needs and problems and, during the course of needs analysis and problem solving, attempt to apply theories learnt and experiences gained previously. Subsequently, the student has to learn to evaluate the effectiveness of care given and make the appropriate changes that may be required. Learning through clinical experiences is far more diverse and pervasive than is conceived. Effective facilitation of learning in the clinical setting and the supervision and assessment of clinical practice are challenging. The most complex skills such as the ability to translate theory into practice are likely to take longest to develop (Moriaty et al 2010). If students are to learn to ‘think’, the thought patterns required by the practitioner need to be determined as successful clinical practice requires the highest level of intellectual functioning – namely that of application, synthesis and evaluation (Stengelhofen 1993). Boud et al (1985:7) ask the following questions about experience-based learning: • What is it that turns experience into learning? • What specifically enables learners to gain the maximum benefit from the situations they find themselves in? • How can they apply their experiences to new contexts? In order to explore the ‘model for learning from experience’ in detail, each phase is considered in turn, focusing on those issues that, in my view, are important in ensuring that the process of learning through experience is an effective one. First, I consider some of the characteristics of the nature of experience for learning. It is perhaps appropriate to start by considering what the word ‘experience’ could mean in the context of learning and the role of experience in learning. In trying to describe the nature of experience for learning, I am mindful of the difficulty of the task. Within the clinical context, is it what a student has observed, encountered or undergone or is it what a student has done? Or is it all of these? Dewey (1925, in Boud et al 1993:6) considered that experience is not simply an event that happens, but rather than this event has meaning, pointing out that ‘events are present and operative anyway; what concerns us is their meaning’. Following on from Dewey’s ideas of experience, Boud et al (1993:6-7) consider meaning to be an essential part of experience. They suggest that: They go on to point out that experience is not singular or limited by time and place, as much experience is ‘multifaceted, multi-layered and so inextricably connected with other experiences that it is impossible to locate temporally or spatially’. Indeed, in 1938, Dewey pointed out that educational experiences have continuity and integrate with one another so that ‘every experience should do something to prepare a person for later experiences of a deeper and more expansive quality. That is the very meaning of growth, continuity, reconstruction of experience’ (Dewey 1938:47). Work on the cognitive learning theory (see, for example, Ausubel 1968) also tells us that learning always relates in some way to what has gone on before. Boud & Walker (1990) refer to the ‘personal foundation of experience’ of a learner, which is the accumulation of previous experiences. Contributory sources to this personal foundation of experience may be the social and cultural environment of the learner, prior clinical placements and experiences. The social, cultural and professional norms and mores assimilated contribute to the formation of the perceptual lenses through which the learner views, and acts, in the world of work. The response of the learner to new experiences is determined significantly by these past experiences, as presuppositions and assumptions have been developed – the past creates expectations, which influence the present. The present context can serve to reinforce or counterbalance this. What students bring to the clinical area – their expectations, knowledge, attitudes and emotions – will influence their construction and interpretation of what they experience. The way one learner reacts in a situation will not be the same as another. Boud et al (1993) believe that, in general, if an event is not related in some way to what the student brings to it, whether or not they are conscious of what this is, then it is not likely to be a productive opportunity. Even when starting a first clinical placement in a hospital, students will bring memories, feelings and knowledge of hospitals, whether or not they have been in one. It will be a rarity to have a clean slate on which to begin – unless new experience and ideas link to previous experience to form ‘new wholes’ (Ausubel 1968), they will exist as abstractions, isolated and without meaning (Boud et al 1993). Planning clinical experiences is therefore important: they should provide continuity rather than being separate and discrete. Furthermore, students should be assisted to make links and connections between experiences to provide new meanings and enable them to ‘see’ new whole pictures. This encourages a deep approach to learning (Marton & Säljö 1984) in which students seek an understanding of the meaning of what they are learning, relate it to previous material and interact actively with the material at hand. Most people would agree with Boud et al (1985:7) when they state that ‘experience alone is not the key to learning’. Dewey (1938:15) was critical of how experiences were offered to students. He asked this question: Students were then rendered callous to ideas and lost the impetus to learn. Does this still happen in the education of health care professionals today? Boud et al (1993) believe that experience cannot be considered in isolation from learning – experience is the central consideration of all learning. Although experience is the foundation of, and the stimulus for, learning, it does not necessarily lead to learning unless there is active engagement with it. Aitchison & Graham (1989, in Critocos 1993:161) state that: Working with experience in the manner suggested by Aitchison & Graham is the key to learning from experience. For learning to take place, the experience need not be recent. We may return to the same experience again and again and draw different meanings from each ‘visit’. Boud et al (1993:9) believe that ‘learning occurs over time and meaning may take years to become apparent … learning from it can grow, the meaning can be transformed, and the effects of it can be altered’. The meaning of experience is not a given: it is subject to interpretation. Only the person who experiences can ultimately give meaning to the experience. It is the learner’s interaction with the learning milieu that creates the particular learning experience (Boud & Walker 1990). No matter what external prompts there might be – mentors, interesting opportunities, resources – learning can occur only if the learner chooses to engage in, and with, the experience. The emphasis in experiential learning is thus on the process of learning. It proceeds from the assumption that ideas are not fixed and immutable elements of thought, but rather are continuously derived from, and tested out, through experience (Kolb 1984). Kolb’s well-known model of this learning process is termed an ‘experiential learning model’ to emphasize the important part that experience plays in the learning process. Learning is conceived of as a four-stage cycle, as shown in Figure 9.1. The here-and-now personal experience is real and concrete, and forms the focal point for learning ‘giving life, texture and subjective personal meaning to abstract concepts’ (Kolb 1984:21). The core of the model is the translation of experiences into concepts through reflective activities. These concepts are subsequently used to guide and inform new experiences. Each phase of the ‘model for learning from experience’ (Chapter 9) will now be considered in detail. • An outline of the aims of the placement and a broad structure of what is to take place. These should be agreed jointly between the practice educator and the student after the first meeting/interview has taken place, as discussed in Chapter 6. • An introduction to staff, resources and learning opportunities that are available to help the student during the placement. Suggestions on how these may be used to help the student learn are discussed in Chapter 8. Those resources and learning opportunities that are specifically required to enable students to achieve their learning intent should be identified. • Students should have the opportunity to seek clarification. As discussed in an earlier section, what the learner brings to the clinical setting has an important influence on what is experienced and how it is experienced: these factors, including the individuality of the student, should be taken into account during the preparatory phase. The other important element to consider is ‘learning intent’ (Boud & Walker 1990:64). Intent can be regarded as a personal determination – there is a clear reason for being there, which prompts learners to take steps to achieve their goals. The learning outcomes of a formal educational programme may influence the learning intent. Boud et al (1985) believe that intent to learn for a particular purpose can assist in overcoming many obstacles and inhibitions. Intent can be determined only by direct reference to the learner. For example, during a particular placement the student’s intent may be to develop communication skills with very ill patients and their relatives. This intent will influence how the student is likely to experience these types of care situations – it acts to focus and intensify, or play down, perceptions in relationship to these experiences. ‘The intent can act as a filter, or magnifier’ (Boud & Walker 1990:64); these authors give the example of the photographer who, when using a zoom lens, will see certain things more clearly but in the process of doing so eliminates other things from the frame. Students may arrive at a clinical placement with little conscious learning intent or even commitment to being there. Unless the mentor can assist the student to form an intent during the preparatory phase, opportunities for learning will not be well utilized owing to a lack of focus; this is likely to result in superficial learning. Mentors can play an important role in helping students to clarify their intent and guide and direct students to the appropriate learning opportunities in the clinical setting. Mentors should be careful that they do not impose their own intents on the student. A discrepancy in intent between the mentor and student may lead to unproductive experiences and considerable frustration for both parties (Boud & Walker 1990). Typically, during the preparatory phase there will be a high level of anxiety. Based on the well-documented evidence of student anxiety and stress in clinical settings (see Ch. 8), time should be spent in assisting students to identify and voice their concerns so that ways may be found to reduce their stress and anxiety and increase their confidence. Knowledge that they will not be alone and will not be expected to do more than they are able to will provide reassurance and make students feel less vulnerable. Boud et al (1993) believe that support, trust and confidence in students can help to overcome past negative influences and allow them to start to act and think differently. Similarly, conditions of threat or lack of confidence in the student are usually antithetical to any new motivation the student may have and serve to reinforce any negative images the student may already hold. • Why has this particular experience – e.g. the care of a certain patient, a visit to another department – been arranged? • What can be learnt through this experience? • How can learning from previous experiences be linked to this experience? • How can students be assisted to plan thoughtfully so that they ‘[act] deliberately, [observe] the consequences of actions systematically and [reflect] critically on the situational constraints and practical potential of the strategic action being considered’ (Carr & Kemmis 1986:40)? • How can students be assisted to engage in the clinical experience so that it means ‘living through actual situations in such a way that it informs [them] of the perceptions and understandings of [other similar] subsequent situations’ (Benner & Wrubel 1982:28)? Answers to these questions are of course not straightforward, as each clinical situation is different. However, if ‘coaching’ (Schön 1987:20) of the students starts during the preparatory phase, they can be assisted to extract maximal learning through their experiences. Boud & Walker (1990) believe that there are two aspects of experience–based learning that are necessary to enhance the working of the processes for learning through experience. The first aspect is noticing, by which the student becomes aware of the event or particular things within it. The second aspect is intervening, in which the student takes an initiative and is active in the event. I see noticing and intervening as two prerequisite skills for learning through experience. Developing noticing skills: Boud & Walker (1990:68) define noticing as ‘an act of becoming aware of what is happening in and around oneself’. It is active and seeking and involves a continuing effort to be aware of what is taking place in oneself and in the learning experience. As well as paying attention to the happenings around the care-giving situation – the experience – it is equally important that students pay attention to what is happening in themselves. They need to be aware in three areas: Being aware of how they are acting and what they are thinking can alert students to what might be influencing them in the event. Being aware of how they are feeling will make students more aware of their emotional responses to the event in order for these to be attended to. Attending to feelings involves being sensitive to the situation: seeking to detect the nuances and the affective climate, as well as what is overt. Neglect of emotions can lead to a build-up of ‘stress and a numbing of awareness which can inhibit the ability to act and distort learning’ (Boud & Walker 1990:69). Stuart (2000) gave the example of midwives being in constant contact with women in pain during labour without acknowledging their own feelings and thoughts. This may eventually lead them to become less sensitive to the needs of women during this time. Noticing provides students with the basis for becoming more fully involved in a care-giving situation and enables them to ‘reflect-in-action’ (Schön 1983) as they become more aware of the processes of how decisions are made to inform actions taken. It is essential to the initiation of the reflective processes during the third phase of the ‘model of experience’ so that sufficient information is retained for retrospective analysis and interpretation of practice after the event. Noticing seems to be a skill that has to be present to cause the experience to be the basis for learning (Stuart 2001). Stuart (2001) found that students in her study who did not know ‘how’ and ‘what’ to notice were unable to enter into experiences and subsequent reflective interactions with their experiences. As two frustrated student midwives said: As can be seen from the excerpt above, virtually every care event has the same meaning for these students. These students did not know how to notice. The starting point for the learning process in order to unearth meaning through experience is noticing – paying close systematic attention to detail, noticing exactly what occurred, including any thoughts, feelings, actions and reactions. Developing the skills of noticing will help students utilize their ‘observer’ status to benefit – how this status can be used for learning is poorly understood and has robbed students of valuable learning opportunities (May et al 1997). This has contributed to the unpopularity of the observer status (Neary 2000). Paying attention to those aspects suggested in Box 9.1 will assist in the development of noticing skills. Learners can be directed to use these aspects in a general way, which will lead them to notice things that might have gone unnoticed otherwise. Alternatively, the mentor can indicate specific aspects to be noticed to help the learner achieve particular learning intents. For example, if a student wishes to learn how to assess the needs of clients at home following major orthopaedic surgery, the student could be directed to notice specific aspects about individual clients visited. The following example is based upon and extended from the work of Stengelhofen (1993). The setting: We are visiting Mrs Jones for the first time today since her discharge from the general hospital 3 days ago following internal fixation of her fractured neck of femur, which she sustained after a fall 6 weeks ago. She is 84 and lives on her own in a terraced house. 1. Start observing when we reach the house: 2. During discussion with her: 3. What does she think are her major concerns/difficulties? 4. What do you think are her major concerns/difficulties? What do you think could be causing these concerns/difficulties? 5. Observe her functional activities. Can she manage important manoeuvres such as using the stairs, sit-to-stand and vice versa, independently? 6. How does she get her food supply? Can she manage activities of living such as washing, dressing, preparing a meal, cleaning the house, independently? 7. What are your thoughts and feelings about someone like Mrs Jones living on her own? Developing intervening skills: Intervening is when the learner takes an initiative and is active in the event (Boud & Walker 1990). This can be any verbal or physical action taken by the learner within the learning situation. Learning through experience is an active process that involves the learner not only in noticing but also in taking initiatives to extend and test their knowledge. Looking on is no substitute for active involvement, as the learner who intervenes is adopting an active approach to the experience and is therefore likely to make more of the potential for learning from the event. The learner’s personal foundation of experience will influence interventions taken – it can either be limiting or act as a trigger for further actions. Boud & Walker (1990) believe that the greatest barriers to intervention are past failure and feelings of inadequacy or embarrassment, which inhibit clear thinking. These negative self-images can paralyse learners so that they are unable to perform or they act so maladroitly that learning opportunities are lost. On the other hand, past success and feelings of confidence and willingness to ‘give it a go’ can carry the learner through initial periods of discomfort. During the preparatory phase, the best way to help learners to intervene is to attend to those feelings that are blocking their ability to act (see, for example, Rogers 1996, for strategies for unblocking blocks to learning). Learners need to learn the skills to be players. They need to know how and when to intervene and the nature and content of the interventions. Many clinical situations require the exercise of technical skills. Knowing how to perform these, such as doing a bed bath, changing an intravenous infusion, removing a urinary catheter, can act as great confidence boosters as the learner can intervene directly. Learning how and what and when to intervene is learning how to cope with the experience, as one major concern of students is knowing ‘how to cope in clinical’ (White & Ewan 1991:108). Typical care events could be analysed and suitable responses rehearsed. The use of role plays, case studies or audio or video recordings of typical events, followed by rehearsal of intervention strategies, will enable learners to practise appropriate intervention sequences. This will help them overcome anxieties and uncertainties and develop a degree of confidence before entering unknown situations. Prior to the experience (e.g. before going to the patient/client) it may be possible to predict what common chain of events may arise and a range of strategies can be developed and discussed with the learner. The learner could be asked searching questions such as ‘Knowing what you know about Mr Johns, what problems do you foresee? … What care do you think he needs? … What actions would you take?’. The mentor may suggest particular interventions that the learner could implement or ways in which the learner’s own ideas could be put into practice. Because of the uncontrollable and unpredictable milieu surrounding clinical situations, not all the possibilities available in practice can be anticipated. Boud & Walker (1991) believe that it is neither possible nor desirable to cover every eventuality – part of learning from experience is dealing with the unexpected when it arises. There should, however, be sufficient preparation to ensure that learners can act effectively and that they are able to remain conscious of what they want to learn.

Learning through clinical practice

unearthing meaning from experience

Introduction

The model for learning from experience

Experience-based learning

The nature of experience for learning

The ‘Model for learning from experience’

The preparatory phase

Focusing on the student as a learner

Focusing on noticing and intervening skills to help students learn through clinical experience

How long does she take to answer the door?

How long does she take to answer the door?

Note the use of any walking aids – is she using them correctly?

Note the use of any walking aids – is she using them correctly?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Learning through clinical practice: unearthing meaning from experience

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access