Introduction

This chapter is about learning and working as a nursing student in a multicultural world. It focuses on the importance of diversity in the modern health service in the 21st century, both from the perspective of the nurse as care-giver and the perspective of the patient or client as a recipient of care. Throughout the chapter the importance of cultural issues in nursing practice are addressed.

The diversity of the population in northern Europe has increased dramatically over recent decades. This has both enriched our societies and also caused us to reconsider many practices that have been taken for granted. An example is given in Case history 5.1.

Case history 5.1

Religious dress and social norms in nursing

Increasingly the nursing profession in the UK is attracting students from a wide variety of religious faiths. This brings with it issues to do with dress as an expression of faith and cultural identity. A group of female Muslim health care students at a large university felt that the uniform regulations of the university did not allow them to express their faith fully, as it expected all students to conform to the standard policy of wearing a semi-fitted short-sleeved tunic-type jacket and trousers. Many of the students were wearing a variation of their religious dress as uniform. The students made representation to the senior level of management within their university to try and obtain some guidance about what they could wear that would allow them to express their faith and care for patients at the same time. The university authorities sought a compromise between the students who wished to wear their traditional dress and the university and partner hospital trusts who their dress to be more in keeping with a nursing uniform. A decision was made that enabled the students to wear looser trousers, a longer tunic with long sleeves, which could be rolled up when giving care, and a hijab (headscarf), providing it was clean and laundered daily and tucked into the tunic. This compromise was acceptable to the students.

Comments and discussion

There are health and safety implications for health professional staff when they wear their own clothes as uniform. Uniform is manufactured to be washed at a high temperature to ensure destruction of micro-organisms and ensure stain removal. Personal clothing may not stand high-temperature washes, and additionally it is not acceptable to allow one’s own clothing to be soiled by patients’ body fluids. A flowing dress of any kind, religious or not, may interfere with manual handling operations and long skirts may sweep the floor if a nurse bends down, for example, to empty a catheter bag. This has implications for cross-infection from micro-organisms in floor dust. Long sleeves are in danger of being contaminated by patients’ body fluids, so it is essential that sleeves can be rolled up when performing nursing care.

In instances where uniform is a problem, both sides should continue their endeavours to seek a negotiated solution and should not walk away from the issue.

From this case history it becomes clear that the students’ wishes were being respected, but within the constraints of current knowledge about infection control and the need for patients to feel secure in the knowledge that the person caring for them was a legitimate practitioner. So let us consider how such radical changes have developed and impacted on everyday nursing practice.

It is clear that, since the formation of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1948, there have been changing needs in the health care requirements of the population of the UK. Prior to the formation of the NHS, provision of health care was from a mixture of local authority, charity and government sources – an eclectic mix of services which left many people lacking in provision and some with none at all. The National Health Service Act in 1946 effectively nationalized health care provision and brought the majority of services under the control of the Ministry of Health, with some under the control of local authorities. A reorganization of services in the early 1970s saw all services united under government control. The formation of the NHS was predicated upon a comprehensive service, free at the point of delivery to all. Very quickly it became clear that there were neither the monetary nor staff resources to meet the demand, and some staff shortages were met by recruiting heavily from Commonwealth countries in the 1950s and 1960s (Webster 2002).

Along with those recruited into the NHS from Commonwealth countries such as the West Indies, people, including health care workers, have come to the UK from many other countries since the inception of the NHS – for economic reasons, as invited workers, as political refugees, or to escape persecution because of their beliefs. From the 1960s, immigration into the UK increased, with people arriving from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Hong Kong and more recently from African and eastern European countries. The formation of the European Union (EU) further opened up opportunities for workers from EU countries to seek employment in the UK. Thus, in the early 2000s, the sociocultural make-up of the UK is such that the black and minority ethnic population of the UK constitutes 7.6% of the total population, up from 1% in 1950. The Department of Health (2003) stated that the Greater London area contains half of all people from the black and minority ethnic population of the UK, with the totals in individual London boroughs ranging from 5% to 50%. The West Midlands, Greater Manchester and West Yorkshire also have black and minority ethnic residents, with 84% of the total black and minority ethnic population of the UK living in the four areas mentioned. Leicester and Birmingham are predicted to increase their black and minority ethnic populations to a majority by 2010 (Department of Health 2003). This has important implications for health care provision in these areas and for nursing. But we must be in no doubt that, in this third millennium, the UK is a multicultural society and part of a multicultural world.

With increasing international travel and migration since the end of World War II, the majority of the world’s countries now contain more than one cultural or ethnic group. But multiculturalism is not just about different races and different colour of skin, it is also about the traditionally distinctive and diverse cultures of all countries of the world including the UK. Indeed, the islands that make up the UK have within their borders groups of people who each see themselves as culturally distinct from their neighbours. People are proud of their Scottish, Irish, Welsh or English ancestry, and of the cultural dimension of that ancestry. They are also as proud of the fact that they may be highland or lowland Scot, mountain or valley Welsh, Londoner, Liverpudlian or Bristolian English, rural or urban dweller. History tells us that over the years the UK has become a host country to many groups of immigrants. Even within one single society it can be argued that it contains many different cultures. Men and women and boys and girls, old and young, ill or healthy, all these groups in any society are expected to behave in ways that their culture determines is appropriate for them.

Multiculturalism in health care provision

Cultures are also divided into subcultures. For example, the NHS can be said to be a subculture of British society, and, within the NHS, nursing, medicine and physiotherapy, for example, can be identified as further subcultures. Each subculture has its own clear and distinctive set of implicit guidelines for behaviour. New entrants to health care professions are often referred to as needing to be ‘socialized’ into their professions. It is clear that health professionals do form a separate cultural group within society, but can the same be said for patients? Is there a ‘patient’ culture?Helman (1994) states that society divides up its members according to their health status as ‘healthy’ or ‘ill’. However, this may be a label applied by a health professional to a person rather than by the person themself.

There are also other ways of dividing society up into categories of subcultures. The 1991 census was the first to elicit information about ethnic origins of the population of the UK, and the 2001 census added to this with questions about dis-ability and religious affiliation. The percentage of black and minority ethnic groups is not currently high, but according to James (1995) this is likely to double over the next 40–50 years. Without doubt, each different cultural and minority ethnic group adds value to the diversity and complexity of UK society. Valuing the cultural background of each and every client and patient is crucial in the provision of culturally aware, culturally sensitive and culturally competent nursing care. Valuing diversity in caring is an important and fundamental issue for health care provision and for nursing in the UK.

Cultural perspectives of health and illness

Cultural determinants of health and illness and of life and death and the understanding of such perspectives is important in contemporary society where diverse communities of people hold differing beliefs and values. The knowledge and explanations of their health and illness that indigenous British people use is based upon a Western tradition of medicine. This has its roots in ancient Greek scientific thought together with an understanding of the nature and causation of disease brought about changing knowledge since the middle ages. Immigrant peoples bring with them their own explanatory models of health and illness which may stem from different beliefs about health and disease. Understanding the differences between these assumptions and beliefs about health and illness provides a basis for healing. With such a diverse population, learning about each individual religious or ethnic grouping within the UK is no mean task for you to undertake, and it may not actually be necessary. Looking at your own culture and/or religion and working out how to explain this to someone from another cultural or religious group may be a useful first step in recognizing and valuing diversity. Read the two Case histories of people from very different cultural backgrounds and think how their views reflect your own beliefs. The first (Case history 5.2) is of Jack who is a native of Newcastle; the second (Case history 5.3) is of Chooi, a woman of Chinese-Malay origins.

Case history 5.2

Jack’s view of his diet and his health

Well, I was brought up on chips and peanut butties (sandwiches) for breakfast and lunch. We used to have potato scallops for tea with some gravy on them and then at about 10 at night me Dad would go down to the chippie for a round of fish and chips. On Sundays we’d have a proper meal of roast chicken. This was pretty much like what all my mates would have. Now I has me lunch at the pub, a couple of rounds of beer and a bag of crisps and go home to a fry up that me wife does for me. My health? Well the doctor says I’ve got to lose weight on account of my blood pressure being that high, stop smoking and take some exercise. I guess the pills he’s given me will do all that for me.

Case history 5.3

Chooi’s beliefs about diet and health

My family are quite strict Buddhist and so we are vegetarians, but that means we eat a lot of fruit and vegetables as well as rice at every meal. We see food as being strongly linked to health; it is like a medicine and at different seasons of the year if we are ill we eat different kinds of food to make us strong and healthy. We see health as a balance between the different elements in the body and we eat foods to keep those elements in balance.

What is culture?

In order to explore the concept of diversity in caring, we first need to define what we mean by culture. Culture has many meanings. When some people talk of culture they are referring to art, opera and music; to others, culture can mean the distinguishing characteristics of a workplace. For example, we often talk of the culture of the NHS, the culture of the armed forces or of the civil service. From an anthropological perspective culture is taken as meaning the set of guidelines that individuals use and which tells them how to behave in their own particular part of society. We can tell from this definition that anthropology is the study of people and their relationships within their social setting. Helman (1994) uses the analogy of a ‘lens’ through which an individual perceives and understands his or her own world. Anthropology theory suggests that people’s behaviour is partly governed by the specific society in which they grow up and in which they live. Culture provides the guide for determining values, practices and beliefs within any given society. It determines how people accommodate themselves within their own culture because it is related to the way that people live. Culture relates to morality, beliefs, social norms and accepted behaviour. Individuals in any culture are expected to adopt and comply with that culture’s rules. What is acceptable in one culture may not be acceptable in another culture. For example, female circumcision (also known as female genital mutilation and normally abbreviated to FGM) is an accepted and deep-rooted practice in a number of African countries. Ng (2000) stated that, in the 1990s, some 50% of Kenyan girls were still being circumcised, and it was estimated in 1994 that this procedure had been performed on over 100 million girls and women worldwide (Henley & Schott 1999). In the UK, there is legislation in place (Prohibition of Circumcision Act 1985) which prohibits the practice, and the World Health Organization does not support it. However, it is important that nurses understand why such practices are still carried out and to know what practical help and advice they can provide to women and girls on whom this procedure has been performed; see Henley & Schott (1999), or read Waris Dirie’s (1998) personal account of female circumcision in her biography ‘Desert Flower’.

Culture determines how nurses and patients react and respond to the actions of nursing interventions. ‘Transcultural’ nursing, as the term implies, means that the provision of nursing care is to do with a meeting of two or more cultures: the culture of the nursing profession, the nurse’s own cultural background and the cultural background of the patient, and maybe even male/female culture and age/youth culture. Transcultural care thus focuses on issues to do with the way each cultural group understands what health is and the causes of illness, what treatment is intended to achieve and what contribution nursing care makes to the total picture. Our behaviours as people in all our roles in life are learned from observing others in our immediate society, and, in comparing what we do with what others do, we alter our own behaviour to fit in. This is a useful way of describing culture from a health care point of view since it allows us to look at our own nursing culture, and also be concerned with the cultural background of the individuals who become patients and clients of the health care services.

Culture and health care

The NHS was set up in 1948 to cater for the needs of a fairly homogeneous ‘British’ culture. Mares et al, writing in 1985, felt that the NHS had not really begun to take into account the composition of the population in the provision of care. They felt that NHS service provision and staff training were still geared to the way of life, family patterns, dietary norms, religious beliefs, attitudes, priorities and expectations of the majority population. In 1994, Thomas and Dines felt that initiatives by the NHS to meet the health care needs of minority ethnic groups appeared inadequate, and that there was little evidence of what might constitute good practice in this area. Papadopoulos, writing in 1999 about Greek Cypriots living in London, felt that their health care needs had not yet been fully recognized. Vydelingum’s research (2000) indicated that patients of South Asian origin felt a general dissatisfaction with their health care in hospital settings. Despite a number of reports from the Department of Health in the 1990s (e.g. Department of Health 1992) which highlighted the particular needs of minority ethnic groups, it seems that such ideas have not yet been translated fully into action in the NHS, although there is now considerable thought and action in this area.

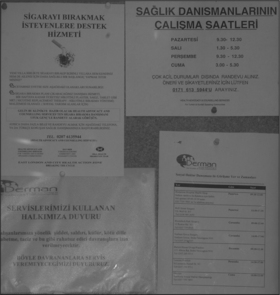

Whatever we might like to think, there are examples of racism and prejudice to be found within the NHS; some might term this ‘institutional racism’. These examples range from not providing interpreter services and using patients’ own young children as interpreters, not providing appropriate food or calling it ‘special’ food, failing to provide services for particular medical conditions common in specific ethnic groups, and failing to adapt patient records to reflect particular naming systems. Yet numerous examples of good practice can also be found. These include health promotion literature in different languages (see Figure 5.1), the provision in some areas of interpreter services for patients, the provision of education for health professionals in the areas of culture and race and the provision of literature for health professionals to consult (e.g. UK Transplant Coordinators Association, undated).

|

| Figure 5.1Health promotion literature in different languages. |

However, James (1995) spells out the health disadvantages that continue to encumber the black and minority ethnic population of the UK. The rates of ill-health and mortality in minority ethnic groups differ from those of the white population and differ between minority ethnic groups themselves. Black and minority ethnic communities face additional disadvantages to those of the indigenous white population in that they are more likely to be concentrated in lower-paid occupations, are more likely to be unemployed, are more likely to live in poor housing and have access only to schools that are poorly equipped. Box 5.1 lists disadvantages that have been identified in terms of health.

Box 5.1

Health disadvantages of black and minority ethnic populations in the UK

• Perinatal mortality: higher among babies born to African-Caribbean-born and Pakistani-born women (Balarjajan 1993, Department of Health 2003).

• Congenital abnormality: higher rates among Asian infants (Balarjajan & Raleigh 1993).

• Coronary heart disease: higher mortality in people from the Indian subcontinent than other racial/ethnic groups (Balarjajan & Raleigh 1993, Department of Health 2003).

• Hypertension, cerebrovascular accident: higher prevalence among people from the Caribbean, Asia and African countries (Balarjajan & Raleigh 1993, Department of Health 2003).

• Diabetes: the incidence among people from the Indian subcontinent can be four times higher than among the UK white population (Department of Health 2003).

• Mental health: suicide rates among young Asian women and diagnosis of schizophrenia in men of African-Caribbean origin are higher than the national average (Balarjajan & Raleigh 1993, Department of Health 2003).

• Cancer and palliative care: services are accessed less frequently by minority ethnic groups (Department of Health 2003).

• Dental health: children in all minority ethnic groups, especially Pakistani and Bangladeshi children, are less likely to have visited a dentist (Department of Health 2003).

• Smoking: rates are higher among minority ethnic men, including black and Irish, and especially Bangladeshi men (Department of Health 2003).

James (1995) and Nazroo & Smith (in Macbeth & Shetty 2001) identified some major influences on health and illness in these particular cultural groups. We need better understanding of the aetiology of illness in these groups and among all minority ethnic populations within the UK. It is not enough to say ‘it is cultural differences’. This is a view echoed by Macbeth & Shetty (2001) in the introduction to their book ‘Health and ethnicity’. This book aims to ‘explain the diversity in “biomedically” measurable health conditions due to determinants and factors that can be called ethnic’, and acknowledges that, although we explain ideas of illness and health within a Western biomedical model, ‘this in itself is a cultural phenomenon’.

Defining health

Lewis in Macbeth & Shetty (2001) discusses the meaning of health in a cultural context and makes the important point that in some cultures it is not possible to find a word that means the same as health. If the word ‘health’ is not translatable into another culture’s language, then this has crucial implications for that culture’s understanding of what health means to them in the context of the UK health care system. Indeed, even in English, there is confusion about the term health. As Lewis points out, it can include illness, and it is said that the NHS is a misnomer since it is mainly about the treatment of illness and disease.

When it was founded in 1948, the World Health Organization took its definition of health to be ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. This is such a lofty ideal and is probably unattainable, representing a wish rather a reality. The ancient Greeks defined health as the four body humours (blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm) in balance; a biomedical definition would centre around the concept of perfect homeostasis. It is clear, however, that health means many different things to people of the same and different cultures, and this causes problems when trying to define and provide interventions for illness and disease, as well as health promotion initiatives. Defining illness and disease is problematical too. If someone has diabetes, there is a lack of the glucose-controlling hormone insulin. Diabetes can thus be recognized as a hormone-deficiency disease, but does this make that person ill or unhealthy? Disease can be diagnosed by examining the results of minute changes in body biochemistry, yet that person may show no signs of illness and indeed will not feel ‘ill’.

A couple longing for a child may need to embark on lengthy and expensive medical interventions to help them conceive. Are they ill? This question needs to be asked because it is only the NHS or a private health service that can provide the intervention necessary to assist conception.

The impact of Western beliefs on other cultures

The global spread of the Western biomedical view of health may have radically altered the perception of health and illness in other countries. As part of a medical team working for an international expedition in a jungle village in Peru in the 1980s, my medical colleague and I were able to persuade a family that saving up their hard earned cash to take their child to the USA for treatment would be to no avail, since even the advanced medical systems of the USA had no cure for microcephaly (congenitally small brain). This family had the view that Western medicine could provide a cure for literally everything, and this view was further supported by our presence in their village with our antibiotics, de-worming medicines, iron tablets and injections and powdered baby milk. Our primary aim and purpose was to provide medical care for expedition members, and I wonder now about the ethics of providing the indigenous population with a very limited amount of help for their acute problems. We were there for 6 months. Did we have a right to impose our health system on theirs, even if they did see it as superior and cure-all, and when we departed to leave them with nothing? Yet would we have accepted their health system had anything gone wrong with any of us? Probably not. The point is that there are so many different explanatory models worldwide for health and the causes of illness that the health care system in any one country cannot possibly encompass them all. Any system has to follow the prevailing medical culture, which in the UK NHS is the Western biomedical model. UK doctors and nurses will explain disease and illness and treatment and nursing care in predominantly biomedical terms. UK-educated nurses and doctors will not find this problematical, yet they may have to adapt their explanations for people from different cultures who have not been exposed to the UK health care system. However, Helman (1976), in ‘Feed a cold and starve a fever’, found that even the predominantly middle-class patients from outer London used in his research still explained their illnesses with reference to ancient Greek theories of hot and cold and the four humours (blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm).

Alternative beliefs about health care in the UK

The last 20 years or so have seen a significant growth in the UK of complementary and alternative approaches to medicine and health care. Complementary and alternatives are defined in the sense of their relationship to biomedicine. Thus, every town now appears to have its alternative health practice, such as homeopathy, osteopathy and chiropractic as alternatives to biomedical medical treatments, orthopaedics and physiotherapy. A complementary health practice may offer aromatherapy, reflexology and a massage as complementary to biomedicine, working alongside it to assist the healing process. Health systems from other countries are also in operation in the UK, such as Chinese herbal medicine and Ayurvedic approaches to health and illness care which originate from the Indian subcontinent. Although some alternative medicine may be available on the NHS (e.g. osteopathy), such approaches are characterized by their cost to the client at the point of delivery, in contrast to the NHS which is mainly free at the point of delivery. Although this situation is changing gradually, the problems of their acceptance in the UK are the continuing general antipathy of the health professions towards them and the fact that most (apart from osteopathy and chiropractic) are not currently regulated in the same way that the traditional biomedical professions are. However, this is changing and in a few years all the major therapies will only be practised legally by registered practitioners.

Why do people brought up in the Western culture of health and illness consult alternative and complementary practitioners and other sources of help? The answer has to be that for many people, especially those with long-term health problems, Western biomedicine does not meet their needs.

With these issues in mind there is much that nursing can do to acquire the knowledge and understanding to be culturally aware and to provide culturally sensitive and culturally competent care, as well as to acknowledge cultural diversity in health care.

Diversity and health care: empowering the NHS

Recognizing diversity

With the growth of the black and minority ethnic population in the UK and the understanding that the UK’s indigenous population is culturally diverse, there has been a clear move in recent years to attempt to understand the cultural dimension of health and disease as well as an attempt to understand those issues to do with race and ethnic origin that impact upon a person’s health. Thus government policy has moved towards creating a strong strategy to focus on equality and diversity within the NHS plan, both in terms of employment and in care delivery (Department of Health 2003). The NHS plan, which was published in 2000, deliberately set out to put patients and people at the core of the health service, and recognized the need to empower people to work differently to deliver services which the diverse community of the UK requires. Whilst much has been done to acknowledge equality and diversity issues in the NHS, the Department of Health concedes that there is still much that needs doing in this area. The Department of Health (2003) in defining equality and diversity states that equality is ‘essentially about creating a fairer society where everyone can participate and has the opportunity to fulfil their potential’. Diversity is seen as the ‘recognition and valuing of difference’ where people are expected to participate in ‘creating a working culture and practices that recognize, respect, value and harness difference for the benefit of the organization and the individual’. There is an emphasis on the valuing of difference that has not been stated in previous policy documents. It suggests recognition that differences make people unique and that commonalities ‘connect us all for the benefit of the organization and the individual’. To reflect the changing mood towards equality and diversity in the UK, the government is seeking to merge a number of organizations – the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE, http://www.cre.gov.uk), the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) and the Disability Rights Commission (DRC) – into one body.

Quality aspects of supporting diversity

The NHS plan in terms of providing a quality service and promoting equality charges health and social care providers to make sure that:

• Public services are accessible and responsive to the needs of all users.

• All public sector bodies work to promote equality and work to eliminate discrimination, and that the public sector leadership implements such requirements.

• Employment strategies in the public sector promote equality and diversity.

To ensure there is a direct impact on improving patient care, the NHS is expected to invest in the training and development of its workforce in order to eliminate discrimination and harassment, to improve diversity and to improve the working lives of its employees. It is the job of local health service managers at the strategic level to ensure that these government imperatives are acted upon and that such ideas become translated into reality for patients and all workers in the health and social care sectors.

The NHS employs over 1.2 million people in its workforce (September 2002). Within such a large workforce we could expect to see a wide and representative distribution of the population as a whole with representation from across the full age range, equal distribution of both genders at all levels of the organization, a meaningful representation of workers from black and minority ethnic groups, workers who are disabled, workers from a number of different religious orientations, workers of various sexual orientations and workers from all kinds of families (Figure 5.2). The NHS plan states that, as an employer, the NHS is committed to equality and positive recognition of diversity, and seeks to attract people from a wide range of backgrounds and communities to work for it. It would seem unwise to establish ‘quotas’ for people of differing backgrounds to work for the NHS, but perusal of the statistics makes it clear that there is still much work to be done in the area of equality of opportunity. The employment statistics for the NHS workforce in 2002 indicates the following:

• 103 350 doctors.

• 367 520 qualified nursing and midwifery staff.

• 116 598 qualified scientific, therapeutic and technical staff.

• 15 609 qualified ambulance staff.

|

| Figure 5.2A member of the health care team. |

These people were supported by a further 689 364 staff working in support and other roles such as porters, cleaners, secretaries, managers, drivers.

The proportion of female medical staff working as consultants has grown in recent years from 17% in 1992 to 24% in 2002. The male/female ratio of medical students has changed over time so that now medical school intakes comprise about 51% women (see Activity 5.1). This increase in female doctors is an important factor in terms of choice for clients in the NHS. With policies that value diversity and insist on it being respected, the NHS should increasingly be able to accommodate such requests and requirements. Consider Case history 5.4, for example; how do you think Amina was able to cope with these two experiences of the health service? Or consider the case of John (Case history 5.5).

Activity 5.1

Think of the potential implications the changing ratio of female to male medical and nursing staff could have for health care service provision and the kinds of facilities that might need to be developed.

Case history 5.4

Amina

Amina is an 18-year-old Muslim woman who is expecting her first child. Her religion forbids her to be seen by any man other than her husband. During her antenatal care she is attended by a female midwife and her general practitioner (GP), who is male, but there is a female GP available. When Amina was admitted to hospital she was seen by a male obstetrician because there were no female obstetricians.

Later she was admitted for a surgical procedure and was seen by a female gynaecologist.

Case history 5.5

John

John is a 75-year-old who is having trouble passing urine. He has lived on his own since his wife died nearly 20 years ago. He is attended by a female nurse in the accident and emergency department, which he finds intensely embarrassing and asks if he can be attended by a male nurse.

Another approach to ensuring that policies relating to promoting diversity and equality are being respected is through collection of data about the ethnic origin of NHS staff by the government. Since 2001, staff appointed to the NHS have been asked to categorize themselves against a new list which for the first time includes those of mixed race background. The 2002 data indicate that 63% of newly employed NHS workers were white, 4% black, 22% Asian, 8% other ethnic groups, with 3% not stated.

Promoting diversity in nursing

Nursing is often seen as not being a suitable occupation by some minority ethnic groups. This has significant implications for the ability of the NHS to provide a service that supports such populations. The reasons for this attitude may go back to traditionally held values in a number of societies where nursing is considered as being ‘dirty’ work, and not having the same ‘kudos’ or status as medicine. Sadler (1999) reported on a project in a city in the north of England that looked at the reasons why specific minority ethnic groups did not apply for nursing training and sought to encourage applications from these groups so that the workforce could become more representative of the local population. Interviews with sixth formers, health care students, parents and careers advisers indicated that there were a number of negative attitudes held about nursing, including subservience to doctors, low pay, hard work but mentally unstimulating, the ‘bedpan’ image. For some they saw a conflict between the requirement of wearing uniforms and religious requirements, such as wearing the hijab to cover hair, and the issue of nursing men. Measures were put into place to increase knowledge and awareness among the target population and to help people gain the relevant qualifications for entry to nurse training. These initiatives met with success in increasing the number of Asian school leavers coming forward for nurse training. The local NHS trust and the local community hopefully will now benefit in the future from a workforce that is more representative of the local population.

Quality and professional implications of gender preference

Nursing has traditionally attracted more women than men, and the number of men in training has not varied much over time. The traditional Western view is that nursing is ‘women’s work’, and it is sad to report that common stereotypes of men in nursing are still popularly held. Research carried out in Canada (Evans 2002) indicated that prevailing gender stereotypes of men as aggressively sexual, or gay, ‘negatively influence the ability of male nurses to develop comfortable and trusting relationships with their patients’. Clearly this has not deterred men seeking to train for the nursing profession, yet there is still much work to be done in challenging such prevailing stereotypes. Chur-Hansen (2002), in her research in Australia, looked at patient preferences for female and male nurses, and concluded that situations in which patients prefer a male or female nurse are not clear, and that the degree of intimacy in a clinical situation was found to be predictive of same-gender preferences. This is where both male and female nurses find themselves in a dilemma. If a female nurse senses that a male patient is uncomfortable with her care, is the answer to ask a male colleague to take over? If a male nurse senses a female patient’s discomfort, should he ask a female colleague? This is where a balance between meeting a patient’s needs and acknowledging one’s own sensitivities is important. If nurses aspire to ensuring that patients have choice, then there should be no hesitation in asking a nurse of the patient’s gender to take over. The ‘Nursing and Midwifery Council Code of professional conduct’ says that you must recognize and respect the role of patients and clients as partners in their care and the contribution they can make to it.

This involves their preferences regarding care, and respecting these within the limits of professional practice, existing legislation, resources and the goals of the therapeutic relationship.

This can be interpreted that a request or implied preference for a same-sex nurse should be acted upon, but only insofar as professional practice or resources will allow. Any patient has the right to refuse care and the Code of professional conduct, Clause 3, makes it clear that consent must be obtained (including consent by cooperation) before a nurse gives any treatment or care. Nurses should always seek advice from others if they find themselves in delicate situations where a patient refuses care from them because of their gender. It can be argued that the provision of gender-sensitive care is about the provision of culturally sensitive care as well. Culture in this instance is seen in the sense of the differing worlds of men and women, as well as in the more traditional sense.

In terms of gender, it is crucial that we seek to treat men and women as equal in the provision of health care. One area where this aspect is acknowledged as being unmet is in the ‘gendering of coronary heart disease’. Lockyer & Bury (2002), in a literature review, suggest that, for various reasons, less attention has been paid to women’s risk and occurrence of coronary heart disease (CHD) than to men’s risk and occurrence. This has implications for nurses and other health professionals who may view women as lower risk, and it has also influenced such things as the provision of coronary rehabilitation programmes which are predicated upon male needs. When research done on men is applied to women, it may ignore specific needs related to being female and experiencing CHD. Lockyer & Bury stress that women are less likely to be referred for investigative tests, are diagnosed later and are less likely to be recommended for surgery. The idea of ‘gender-neutral’ care put forward by Lockyer & Bury means that nurses make decisions about caring for women with CHD based on their knowledge and experience of caring for men with CHD. Women’s needs are therefore not being met.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access