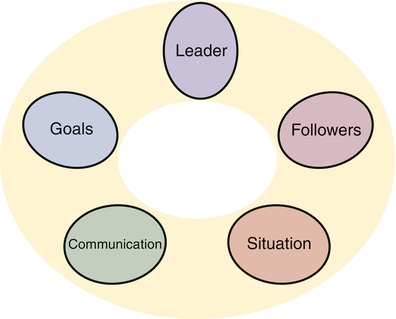

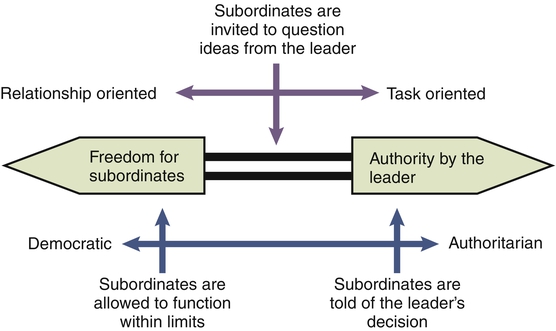

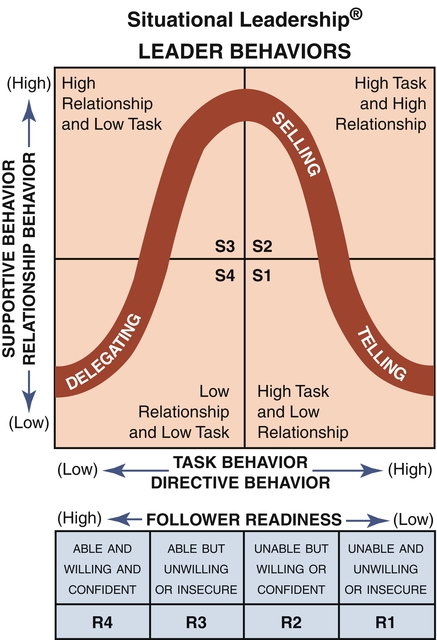

Photo used with permission from Photos.com. In nursing, leadership is studied as a way of increasing the skills and abilities needed to facilitate clinical outcomes while working with people across a variety of situations and to increase understanding and control of the professional work setting. A long history and rich literature surround leadership theories, much of it from outside of nursing. Nursing has drawn from both classic and contemporary thinkers. Bennis (1994) made a strong argument for leadership, stating that quality of life depends on the quality of leaders. He noted three reasons why leaders are important: the character of change in society, the de-emphasis on integrity in institutions, and the responsibility for the effectiveness of organizations. Fiedler and Garcia (1987) argued that leadership is one of the most important factors that determine the survival and success of groups and organizations. Effective leadership is important in nursing for those same reasons, specifically because of its impact on the quality of nurses’ work lives, being a stabilizing influence during constant change, and for nurses’ productivity and quality of care. If the delivery of nursing services involves the organization and coordination of complex activities in the human services realm, then both leadership and management are important elements. The leader’s focus is on people; the manager focuses on systems and structure (Bennis, 1994). Thus although both are used to accomplish goals, each has a different focus. For example, a nurse may use leadership strategies or management strategies to motivate others, but the desired outcome of the motivation is likely to be different. However, leadership and management have some shared characteristics. In this area of overlap, the processes and strategies look similar and may be employed for a similar outcome or blended together to accomplish goals. Leadership and management are equally important processes. Because they each have a different focus, their importance varies according to what is needed in a specific situation. Hersey and colleagues (2013) thought that leadership was a broader concept than management. They described management as a special kind of leadership. This view would position management as a part of leadership, not as a distinct concept. However, according to the definitions, characteristics, and processes, the concepts of leadership and management are different, but at the area of overlap they look similar. For example, directing occurs in both leadership and management activities (the area of overlap), whereas inspiring a vision is clearly a leadership function. Both leadership and management are necessary. Mintzberg’s (1994) idea was that nursing management occurred in an interactive model rather than through a stepwise linear process. An evidence-based approach to differentiating nursing leadership from management was taken to identify discrete competencies through an integrative content analysis of the literature base (Jennings et al., 2007). In 140 articles reviewed, they found 894 competencies, of which 862 (96%) were common to both leadership and management. Thus the overlap area appeared to be larger than previously thought. However, leadership and management do serve distinct purposes. Perhaps it is time to apply leadership and management concepts and competencies by setting, level of role responsibility, career stage, and social context to more fully apply the evidence base to practice. “The nurse leader plays a critical role in the business of the healthcare organization and the quality and safety of the services provided” (O’Connor, 2008, p. 21). Strong evidence for the nurse leader’s critical role both in the business of a health care organization and in the quality and safety of service delivery has been laid out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2004), the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s (ANCC) Magnet Recognition Program® (ANCC, 2008a, b), and the American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE) (2005). The IOM focus is on the following five areas of management practice: • Implementing evidence-based management • Balancing tensions between efficiency and reliability • Creating and sustaining trust • Actively managing the change process through communication, feedback, training, sustained effort and attention, and worker involvement • Communication and relationship management • Business skills and principles • Knowledge of the health care environment Both nurses and the health care delivery systems in which they practice need leaders. Potential health care leaders likely will possess “a passion to make things better, a commitment to values, a focus on creativity and innovation, and the knowledge and skills necessary to identify health care needs and then to mobilize and array the human and other resources necessary to achieve goals and effect outcomes” (Huber & Watson, 2001, p. 29). Exhibiting quiet but respected competence, a leader may be the wise or go-to person within the group, a superior problem solver, a strategic communicator, or someone who is emotionally intelligent and strong in interpersonal relationship skills. Leaders may grow gradually out of a smoldering issue or erupt through a crisis event. Clearly, “something changes as leadership blossoms” (Huber & Watson, 2001, p. 29). 1. Diagnosing: Diagnosing involves being able to understand the situation and the problem to be solved or resolved. This is a cognitive competency. 2. Adapting: Adapting involves being able to adapt behaviors and other resources to match the situation. This is a behavioral competency. 3. Communicating: Communicating is used to advance the process in a way that individuals can understand and accept. This is a process competency. Among the important personal leadership skills is emotional intelligence. Based on the work of Goleman (2007), relational and emotional integrity are hallmarks of good leaders. This is because the leader operates in a crucial cultural and contextual influencing mode. The leader’s behavior, patterns of actions, attitude, and performance have a special impact on the team’s attitude and behaviors and on the context and character of work life. Followers need to be able to depend on role consistency, balance, and behavioral integrity from the leader. The four skill sets needed by good leaders are as follows: 1. Self-awareness: Ability to read one’s own emotional state and be aware of one’s own mood and how this affects staff relationships 2. Self-management: Ability to take corrective action so as not to transfer negative moods to staff relationships 3. Social awareness: An intuitive skill of empathy and expressiveness in being sensitive and aware of the emotions and moods of others 4. Relationship management: Use of effective communication with others to disarm conflict, and the ability to develop the emotional maturity of team members Gittell (2009) emphasized the centrality of relationship management because patient care is a coordination challenge. She noted that relational coordination drives quality and efficiency outcomes and health care performance. Relational coordination is defined as “coordinating work through relationships of shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect” (p. xiii). Relational coordination focuses on relationships between roles rather than between individuals. Most leadership definitions incorporate the two components of an interaction among people and the process of influencing. Thus leadership is a social exchange phenomenon. At its core, leadership is about influencing people. In contrast, management involves influencing employees to meet an organization’s goals and is focused primarily on organizational goals and objectives. Bennis (1994) listed a number of distinctions between leadership and management. He noted that the leader focuses on people, whereas the manager focuses on systems and structures. The leader innovates and conquers the context. Another distinction is that a leader innovates, whereas a manager administers. Kotter (2001) noted that managers cope with complexity whereas leaders cope with change. Leadership is a broad concept and a process that can be applied to any group. Grant (1994) noted that leadership, management, and professionalism have different but related meanings, as follows: • Leadership: Guiding, directing, teaching, and motivating to set and achieve goals • Management: Resource coordination and integration to accomplish specific goals • Professionalism: An approach to an occupation that distinguishes it from being merely a job, focuses on service as the highest ideal, follows a code of ethics, and is seen as a lifetime commitment Leadership can be best understood as a process. Much attention has been focused on leadership as a group and organizational process because organizational change is heavily influenced by the context or environment. Nurses need to have a solid foundation of knowledge in leadership and care management. This applies at all levels: nurse care provider, nurse manager, and nurse executive. However, the depth and focus of care management roles and skills may vary by level. For example, the nurse care provider concentrates on the coordination of nursing care to individuals or groups. This may include such activities as arranging access to services, providing direct care, doing referrals, and supporting a patient’s family. At the next level, the nurse manager concentrates on the day-to-day administration and coordination of services provided by a group of nurses. The nurse executive’s role and function concentrate on long-term administration of an institution or program that delivers nursing services, focusing on integrating the system and building a culture (Mintzberg, 1998). Hersey and colleagues (2013) noted that the leadership process is a function of the leader, the followers, and other situational variables. The leadership process includes five interwoven aspects: (1) the leader, (2) the follower, (3) the situation, (4) the communication process, and (5) the goals (Kison, 1989). Figure 1-1 shows how these components relate to one another. All five elements interact within any given leadership moment. The values, skills, and style of leaders are important. Their internalized pattern of basic behaviors influences actions and the ability to lead. Leaders’ perceptions of themselves, their roles, and their expectations also have an impact on their followers. Self-awareness is crucial to leadership effectiveness and is the focus for many leadership exercises. Internal forces in leaders that impinge on leadership style are values, confidence in employees, leadership inclinations, and sense of security in uncertainty (Tannenbaum & Schmidt, 1973). Interpersonal, emotional, and social intelligence skills also contribute to the effective leadership of knowledge workers (Goleman, 2007; Porter- O’Grady, 2003). Communication processes vary among groups regarding the patterns and channels used and how open or closed the communication flow is. Communicating is basic to the process of influencing and thus to leadership. Almost every issue or problem contains a communication aspect. Through communication, the leader’s vision and message are received by the followers. After choosing a channel, the sender transmits a message. However, the message is filtered through the receiver’s perception. Communication is transmitted through both verbal and nonverbal modes. Organizations include a variety of communication structures and flows. These may be downward, upward, horizontal, grapevines, or networks. Communication may be formal or informal (Hersey et al., 2013). Certain acts performed by leaders have positive effects and make people feel more respected; listening and informal chatting are prime examples (Alvesson & Sveningsson, 2003). Hersey and colleagues (2013) have done a thorough overview of leadership and organizational theory through the situational leadership school of thought. From an early awareness of the leader’s need to be concerned about both tasks and human relationships (output and people) sprang a long history of leadership theories that can be grouped as trait, attitudinal, and situational (Hersey et al., 2013). The trait approach focuses on identifying specific characteristics of leaders. The attitudinal approach measures attitudes toward leader behavior. The situational approach focuses on observed behaviors of leaders and how leadership styles can be matched to situations. Leadership theories have evolved away from an early focus on the traits or characteristics of the leader as a person because it was found that it is not possible to predict leadership from clusters of traits. However, several authors have developed lists of traits common to good leaders (Bass, 1985; Bennis & Nanus, 1985), and interest remains in the characteristics to look for in good leaders. Further background on the history of leadership research can be found online (e.g., www.sedl.org/change/leadership/history.html). In the trait approach, theorists have sought to understand leadership by examining the characteristics of leaders. Presumably, leaders could be differentiated from non-leaders. The trait approach has generated multiple lists of traits proposed to be essential to leadership. Bennis (1994) identified a recipe for leadership that contained six ingredients: a guiding vision, passion, integrity (including self-knowledge, candor, and maturity), trust, curiosity, and daring. Leaders arise in a context, and they are said to be made, not born. They appear to learn leadership skills in stages (Bennis, 2004). Thus leadership skills can be both taught and learned. It is important for nurses to recognize that they can learn, practice, and improve their personal leadership competencies. Drucker (1996) noted that effective leaders know the following four things: 1. The only definition of a leader is someone who has followers. 2. Popularity is not leadership; results are. 3. Leaders are visible and set examples. Leaders are active, not passive. The risk-taking element of leadership involves taking action. Leaders engage their environment with behaviors of doing, influencing, and moving. These are action terms. Pagonis (1992) noted that to lead successfully a leader must demonstrate two active, essential, and interrelated traits: expertise and empathy. Leaders are those who talk about adventures into new territory and take the risks inherent in innovation (Kouzes & Posner, 1995). Leadership means giving guidance and using a focused vision. A leader may see the need to chart a course that is new or unknown, unpopular, or risky because it challenges those with vested interests who have much to lose. In a way, nursing’s struggle for greater economic parity in health care is courageous and risky. Clancy (2003) noted that leaders need to “consistently find the courage to hold true to their beliefs and convictions” (p. 128). Both ethical fitness and moral courage form the backbone of making necessary and hard—but right and unpopular—decisions. Cost containment, patient’s rights, safe staffing, stress and anger, and ethical dilemmas all challenge the leader to identify right from wrong and act from his or her sense of conviction. The leadership courage continuum runs from “good coward” (cannot muster courage to make tough choices) to “reckless courage” (shoot from the hip). Leaders need to be willing to make tough choices plus overcome the fear associated with them. Research by Bennis and Thomas (2002) indicated that extraordinary leaders possess skills required to overcome adversity and emerge stronger and more committed. They suggest that “one of the most reliable indicators and predictors of true leadership is an individual’s ability to find meaning in negative events and to learn from even the most trying circumstances” (Bennis & Thomas, 2002, p. 39). “Crucible” experiences shape leaders. These are trials, tests, and transformative experiences that force leaders to question themselves and what matters and to hone their judgment. Consequently, leaders come to a new or altered sense of identity. Crucible experiences can occur from positive or negative triggers, but leaders see them as opportunities for reinvention. Great leaders possess the following four essential skills: 1. The ability to engage others in shared meaning 2. A distinctive and compelling vocal tone 4. A combination of hardiness and ability to grasp context, called “adaptive capacity” Characteristics such as knowledge, motivating people to work harder, trust, communication, enthusiasm, vision, courage, ability to see the big picture, and ability to take risks are associated with important leadership qualities in research findings. For example, Bennis and Nanus (1985) studied 90 chief executives from 1978 to 1983 and found that there were two key leadership traits. One is a guiding set of concepts, and the other is the ability to communicate a vision. Kouzes and Posner (1995) defined the following five behaviors that correlated with leadership excellence: 1. Challenging the process: Leaders go beyond the status quo to search for opportunities, experiment, and take risks to achieve lofty goals. 2. Inspiring shared vision: Leaders envision the future and enlist others in sharing the dream. 3. Enabling others to act: Leaders foster collaboration and develop and strengthen others so that the whole team performs well. 4. Modeling the way: Leaders set an example and structure events so that incremental progress is celebrated as small wins. 5. Encouraging the heart: Leaders appreciate and recognize individual contributions and formally celebrate accomplishments. These five practices can be seen as the way leaders get extraordinary things done through people in an organization. The practices and qualities of leadership help nurses enrich their own style and contribute to a more productive workplace. This model of leadership has been used in nursing research (Patrick et al., 2011). One research-based nursing model (Mathena, 2002) identified the following six core behaviors critical for nursing leadership success: Although the lists of leadership characteristics and competencies vary somewhat, the functions of visioning, setting the direction, inspiration, motivation, and enabling systems and followers are at the core of leadership activity. Bennis (1994) discussed what has come to be called “the vision thing.” The one specific defining quality of leaders is vision— the ability to create a vision and put it into operation. Leadership is founded on trust: “Trust is the emotional glue that binds leaders and employees together and is a measure of the legitimacy of leadership” (Malloch, 2002, p. 14). Organizations that focus on sustaining a healing culture rebuild organizational trust by focusing on trust in relationships with employees. Behaviors that build trust include sharing relevant information, reducing controls, and meeting expectations. Trust-destroying behaviors include being insensitive to beliefs and values, avoiding discussion of sensitive issues, and encouraging competition via winners and losers. Nurses can be aware of the crucial nature of trust in the leadership and management relationship. Trust goes both ways and needs to be nurtured. Nurses can start by examining their own behaviors and then taking deliberative actions to strengthen trust in the environment. • Task behavior: The extent to which leaders organize and define roles; explain activities; determine when, where, and how tasks are to be accomplished; and endeavor to get work accomplished • Relationship behavior: The extent to which leaders maintain personal relationships by opening communication and providing psychoemotional support and facilitating behaviors Tannenbaum and Schmidt (1973) suggested that a leader might select one of many behavior styles arrayed along a continuum. The continuum ranges from democratic to authoritarian (or subordinate-centered to leader-centered). Their work suggested that there are a variety of leadership styles (Figure 1-2) or points along the continuum. They discussed three distinct styles: authoritarian, democratic, and laissez-faire. Some individuals are able to integrate styles and flexibly match to the situation at hand, but this is rare. Leadership styles appear to have a gender component. The feminist perspective on leadership was presented by Helgeson (1995a, b). She identified female leadership as a weblike structure—dynamic and continuously expanding and contracting. It is characterized by a concern for family, community, and culture. The inclination is for a democratic power style, and the emphasis is on the importance of establishing relationships, maintaining connections with others, and deriving strength from empowering others. By contrast, leadership approaches described by men tend to be influenced by the military and participating in team sports. Men tend to spend their time on meetings and tasks requiring immediate attention, focusing on completion of tasks and achievement of goals. Women tend to focus on process; men tend to focus on achievement and closure. Women tend to be more flexible and value cooperation, connectedness, and relationships. Exploring the feminist perspective on leadership is valuable in that it provides food for thought as health care organizations and the nurses working in them struggle with not wanting to let go of the familiar hierarchy management style yet needing to reconfigure to the circular or web structure to be effective. It is not known whether gender differences are permanent characteristics or are culturally mediated artifacts that blur with time. Leader behavior was described as having two separate dimensions, as follows: 1. Initiating structure and consideration in the Ohio State Leadership Studies 2. Employee orientation and production orientation in the Michigan Leadership Studies These dimensions are similar to the authoritarian (or task) and democratic (or relationship) ideas of the leader behavior continuum. The Group Dynamics Studies highlighted goal achievement (similar to task) and group maintenance (similar to relationship) elements of leadership behavior (Cartwright & Zander, 1960). Blake and Mouton (1964) used task and relationship concepts in their grid, which was later modified by Blake and McCanse (1991). The following five types of leadership or management styles, based on concern for production (task) and concern for people (relationship), emerged: 1. Impoverished: This style uses minimal effort to get the work done. 2. Country club: This approach emphasizes attention to the needs of people to effect satisfying relationships. 3. Authority-obedience: This style strives for efficiency in operations. 4. Organizational man: This approach works on balancing the necessity to accomplish the task with maintaining morale. 5. Team: This style promotes work accomplishment from committed people and interdependence through a common cause, leading to trust and respect. As situations become more complex, leadership becomes more difficult. Fiedler (1967) developed a Leadership Contingency Model to explain how to apply this idea. He classified group situational variables of leader-member relations, task structure, and position power into eight possible combinations, ranging from high to low on these three major variables. Leader-member relations refers to the type and quality of the leader’s personal relationships with followers. Task structure means how structured the group’s assigned task is. Position power refers to power that is conferred on the leader by the organization as a result of the assigned job. Fiedler examined the favorableness of the situation from the perspective of the leader’s influence over the group. The most favorable situation occurs with good leader-member relations, high task structure, and high position power. The least favorable situation occurs when the leader is disliked, has an unstructured task, and has little position power. With Fiedler’s model, group situations can be analyzed to determine the most effective leadership style. Fiedler (1967) examined which style (task-oriented versus relationship-oriented) would be most effective for each of eight situations. A key general principle is that the need for task-oriented leaders occurs when the situation is either highly favorable or very unfavorable. A task-oriented style is needed for situations on the extremes, whereas a relationship-oriented style is needed when the situation is moderately favorable. In Situational Leadership® theory,* leadership in groups is never a static circumstance. The situation is dynamic and subject to change. In a very difficult situation, relationships may be the leader’s preferred emphasis. However, if interpersonal relationships are not an immediate problem or if the group is on the verge of collapse, then strong authoritative direction is needed to get the group moving and accomplishing. For this situation, the task-oriented leader is a more effective match between leader and job. However, groups do not remain static; they move back and forth through stages. When the problem no longer is just the need to get the group moving but also includes solving numerous interpersonal conflicts, a relationship-oriented leader is better matched to the situation. Eventually, as the situation progresses, a relationship-oriented leader can become less effective. This occurs because once the group has less conflict, individuals may begin to coast along and positive motivation may be lost as individuals become apathetic. Once again, a task-oriented style is called for—challenging individuals by using the motivation they need to continue to produce. Because of the factor of constant change, maintaining good leadership is complicated for any group. One way to foster effective leadership is to evaluate leaders according to Fiedler’s contingency model (1967) and then use this information to increase leaders’ awareness of their natural style tendency: relationship-oriented or task-oriented. Fiedler’s measure for leadership style is the Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) scale (Fiedler & Chemers, 1984). The LPC is an 18-item semantic differential scale that is the personality measure of Fiedler’s contingency model (Fiedler & Garcia, 1987). Hersey and colleagues (2013) described the Tri-Dimensional Leader Effectiveness Model first developed by Hersey and Blanchard. First, a two-dimensional model was constructed, in which task behavior and relationship behavior were displayed on a grid from high to low and were divided into four quadrants: (1) high task, low relationship; (2) high task, high relationship; (3) high relationship, low task; and (4) low task, low relationship (Figure 1-3). These quadrants represent four basic leadership styles: telling, selling, participating, and delegating. As applied to the continuum of authoritarian versus democratic styles, telling would be authoritarian and participating would be democratic. The two most common leadership styles are selling and participating. Selling requires the most from a leader, who must provide high amounts of guidance and support. Movement into a participative leadership style requires much less structure and task-directive behavior from the leader because the individual or group is performing but is not quite confident enough in its own ability for the leader to completely let go. The individual or group wants to talk about things.

Leadership and Management Principles

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

LEADERSHIP AND CARE MANAGEMENT DIFFERENTIATED

THE LEADERSHIP ROLE

LEADERSHIP OVERVIEW

Leadership Skills

DEFINITIONS

BACKGROUND ON LEADERSHIP

LEADERSHIP: FIVE INTERWOVEN ASPECTS

Process Part 1: The Leader

Process Part 4: Communication

LEADERSHIP THEORIES

Trait Theories

Characteristics of Leadership

Vision and Trust

Leadership Styles

Feminist Leadership Perspective

ATTITUDINAL LEADERSHIP THEORIES

Situational Theories

Fiedler’s Contingency Theory

Hersey and Blanchard’s Tri-Dimensional Leader Effectiveness Model

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Leadership and Management Principles

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access