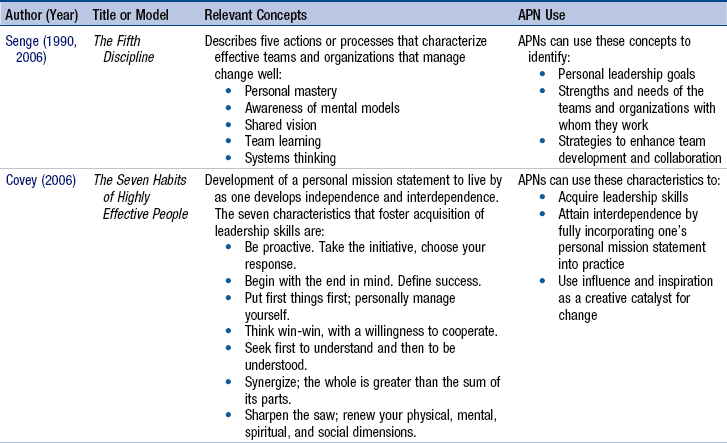

Chapter 11 Context in Which Advanced Practice Nurses Exercise Leadership Competency Leadership Domains of Advanced Practice Nurses Leadership: Definitions, Models, and Concepts Leadership Models That Lead to Transformation Leadership Models That Address Systems Change and Innovation Defining Characteristics of the Advanced Practice Nurse Leadership Competency Attributes of Effective Advanced Practice Nurse Leaders Self-Confidence and Risk Taking Expert Communication and Relationship Building Respect for Cultural Diversity Developing Skills as Advanced Practice Nurse Leaders Developing Leadership in the Health Policy Arena Obstacles to Leadership Development and Effective Leadership Strategies for Implementing the Leadership Competency Developing a Leadership Portfolio Promoting Collaboration Among Advanced Practice Nursing Groups Motivating and Empowering Others Engaging Others in Planning and Implementing Change Institutional Assessment Regarding Readiness for Change More than ever before, the flattening of the world through global interactions (Friedman, 2006), the rate with which change occurs, and the unsettled status of health care make leadership skills a necessity for successful advanced practice nurses (APNs). Leadership is a core competency of advanced practice nursing, but the concept has some unique characteristics in the APN context. Our conceptualization of APN leadership involves three distinct defining characteristics—mentoring, innovation, and activism. Calls for systems redesign and transformation (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2011, 2001, 2000; Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI], 2011; Leape, Berwick, Clancy, et al., 2009), changes in health professional education (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006), and core interdisciplinary competencies for health professionals (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative [CIHC], 2010; Greiner & Knebel, 2003; Health Sciences Institute, 2005; Interprofessional Collaborative Initiative [IPEC], 2011) have important implications for the leadership competency in APN education and practice. To provide leadership in individual patient care situations, APNs must be able to assess the clinical microsystems in which they provide care, understand the macrosystems that influence the smaller systems, determine the need for redesign to improve safety, quality, and reliability, and evaluate the results. In short, systems leaders must be able to identify the need for innovation and change and implement strategies to achieve it. In partnership with others, APNs craft approaches to evaluate, reassess, and implement systems redesign and innovation. APNs exercise leadership in four key domains—in clinical practice environments, in the nursing profession, at the systems level, and in the health policy arena. APNs may exercise leadership activities at local, regional, and/or national levels; their activities may range from taking a stand on behalf of an individual patient to advocating for a change in national health policy. The leadership competency depends on and interacts with other APN competencies. Specific leadership skills should be discussed, nurtured, and developed during graduate education through refinement of communication skills, supported risk taking, reflective learning, and interactions with nurse leaders, mentors, and role models. The recommended movement of APN education to the Doctorate of Nursing Practice (DNP) has implications for the APN’s leadership competency (AACN, 2004). For example, the DNP essential requiring expertise in systems leadership means that the organizational and professional leadership components of advanced practice nursing curricula will need to expand (AACN, 2006). Leading in today’s health care environment is a task of unprecedented complexity for APNs, administrators, and policymakers. To understand the need for APN leadership across the four domains, it is important to understand the factors that are shaping this competency in the twenty-first century. The IOM has issued a number of reports, all of which call for a radical redesign and transformation of the health care system. The groundbreaking report by the IOM, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (2011) states that is essential for nurses to be full partners and leaders in the transformation of health care. In addition, the education of those in the health professions is being transformed. Such changes have not occurred quickly, in part because they require a significant rethinking of how care is delivered, the roles of patients and education of providers, effective channels for diffusing innovation, how health care is financed, and which provider activities count and should be reimbursed (Greiner & Knebel, 2003; see Chapters 19 and 22). The IOM’s call to transform the health care system is predicated on six national quality aims—safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity (IOM, 2001). This far-reaching report has led to numerous assessments and initiatives. For example, the IOM noted that nursing homes are at high risk for the occurrence of adverse events, yet numerous institutional barriers to reporting these events still exist, such as long-standing cultures around naming and blaming individuals rather than exploring gaps in systems of care and organizational culture (Wagner, Capezuti, & Ouslander, 2006). Leaders have come to realize that errors occur because of a continuum of reasons. David Marx, a systems safety engineer, has developed a model to encourage leaders to use open communication and accountability at all levels to optimize organizational safety (Just Culture Community, 2012). Leaders can use these principles to facilitate the evaluation of errors, near misses, and questionable behavior to determine root causes of situations in which employee behavior does not match organizational values. Causes for these situations can range from organizational culture to defective systems and processes to bad choices on the part of employees. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has highlighted a number of innovative examples of health care organizations using Just Culture principles to improve response to errors (AHRQ, 2010). The IHI launched a campaign to save 100,000 lives from medical error (Berwick, Caulkins, McCannon, et al., 2006; Patient Safety and Quality Health Care, 2005). This campaign was so successful, with an estimated 122,000 lives saved, that a new goal was promoted to save 5 million lives, which has had a significant impact on patient outcomes through the reduction of morbidity and mortality (IHI, 2007, updated 2012). Many health care systems are participating in these efforts to improve safety and quality, such as Magnet recognition or participating in the IHI campaign. A recent survey has found that opinion leaders would like nurses to have more influence in the transformation of health care in areas such as reducing medical errors, improving the quality of care, and promoting wellness (Blizzard, Khoury, & McMurray, 2010). These leaders suggest that nurses should take on more leadership roles to have their voices heard. APNs not only have a stake in these efforts, but also have the clinical expertise and leadership that can ensure success. Greiner and Knebel (2003), the Health Sciences Institute (2005), and the AACN (2006) have identified competencies that health professionals must have, including APNs, and many of these relate to the leadership competency. The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, in a 2010 national conference, promulgated recommendations concerning how health care providers need to be trained to meet the needs of primary health care (Cronenwett & Dzau, 2010; Pohl, Hanson, Newland, et al., 2010). A review of research shows that there is no clear data yet regarding the impact that interprofessional education has had on provider practice and outcomes for patients; however, there is enough indication of potential that further rigorous research is warranted (Reeves, Zwarenstein, Goldman, et al., 2009). Although the recommendations for leadership competencies affect primarily educators and the curricula that they design, they have significant implications for APNs already practicing and for the environments in which APN students learn. The IOM has identified five competencies that all health professionals must possess if the redesign and transformation of the U.S. health care system is to be realized: provide patient-centered care, work in interdisciplinary teams, use evidence-based practices, apply quality improvement principles, and use informatics (Greiner & Knebel, 2003). The Health Sciences Institute (2005) has published a model of Continuous Chronic Care and identified five levels of change. At the provider level of change, they identified three major competencies: promote health and prevent disease; manage diseases and disease impacts; and promote consumer independence and life quality. More recently, there has been a resurgence of interest in major competencies to encourage interprofessional collaboration for health care providers (CIHC, 2010; IPEC, 2011). This movement, led by our Canadian colleagues, has an important impact for health care in the United States, and specifically for APNs. APN leaders will participate in creating environments in which these interdisciplinary competencies are not merely supported but can flourish. When APNs and others can implement these competencies fully, the transformation will be underway. In the AACN’s The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice (2006), several specific competencies relate to leadership for all DNP graduates, including APNs. Of the eight essentials, four inform the leadership competency—organizational and system leadership for quality improvement and systems thinking, clinical scholarship and analytic methods, information systems and technology and patient care technology for the improvement and transformation of health care, and clinical prevention and population health for improving the nation’s health. Recent core competencies by the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists (NACNS, 2010) and National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF, 2012) also address leadership requirements of clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). The reader will note that several of these essentials and competencies are consistent with the competencies being expected of all health professionals just described. In summary, numerous contextual and educational factors that require APN leadership have been identified in calls for the redesign and transformation of the health care system. Certain themes are apparent—in particular, patient-centeredness (see Chapter 7), teamwork (see Chapter 12), quality improvement (Cronenwett, Sherwood, Pohl, et al., 2009; Sherwood, 2010), the use of information technology (IT), and complexity. These factors must be considered in APN graduate and continuing education so that APNs acquire the knowledge and skills they need to lead effectively. Although the need for leadership in health care settings is well recognized (Aduddell & Dorman, 2010; Carlson, Klakovich, Broscious, et al., 2011; NACNS, 2011, 2004; NONPF, 2012), the topic has not been well studied, and research on effective leadership is needed (Falk-Rafael, 2005). Not all APNs are comfortable with the idea of being leaders, but leadership is not an optional activity. As noted, the APN leadership competency can be conceptualized as occurring in four primary domains or areas: in clinical practice with patients and staff, within professional organizations, within health care systems, and in health policymaking arenas. The extent to which individual APNs choose to lead in each of these areas depends on patients’ needs, APNs’ personal characteristics, interests, and commitments, institutional or organizational priorities and opportunities, and priority health policy issues in nursing as a whole and within one’s specialty (Carroll, 2005; Leavitt, Chaffee, & Vance, 2007). There is considerable overlap in the knowledge and skills needed across the four domains; for example, developing skills in the clinical leadership domain will enable the APN to be more effective at the policy level. Clinical leadership focuses first on the patient and his or her needs, ensuring that quality patient care is achieved. Clinical leadership is a foundational component to attaining and maintaining a productive environment in which safe and excellent care is provided and professionals assume self-accountability (Murphy, Quillinan, & Carolan, 2009). It occurs when APNs learn with and from others about how to build appropriate working relationships with health care team members, how to instill confidence in patients and colleagues, and how to problem-solve as part of a team (Bally, 2007). APN leaders are role models and mentors who empower patients and colleagues. They propose and implement change strategies that improve patient care and enhance others’ perceptions of the value of advanced practice nursing. Some clinical leadership skills are part of the competencies of consultation (see Chapter 9) and collaboration (see Chapter 12) and are portrayed in the exemplars in the role chapters (see Part III) as well. The most common clinical leadership roles APNs can expect to play are those of advocate (for patient, family, staff, or colleagues), group leader, and systems leader. APNs may advocate for a particular patient or family, as when an acute care nurse practitioner (ACNP) advocates with the attending physician about the need for a better explanation of the side effects of an elective surgery. Writing articles and presenting talks on clinical topics are other ways of expressing clinical leadership and influencing others. APNs often exercise leadership to ensure that clinical problems are addressed by administrative leaders at a systems level. Brown (1989) called this role the “shuttle diplomat” because APNs move between clinical and administrative arenas, interpreting the needs of one to the other. Advancing clinical excellence requires financial, creative, and political skills to promote innovative care and collaborate with others (Murphy, Quillinan, & Carolan, 2009). Having these additional skills improves the success of shuttle diplomacy and the compelling translation of ideas between distinct perspectives. APNs recognize the clinical problems related to their specialty that require attention or intervention from the larger (macro) system of which they are a part. For example, when a CNS called a patient to learn why he had not kept his appointment at the heart failure clinic, she learned that he could not find parking nearby because of hospital construction, did not know that a shuttle would take him from the satellite lot to the clinic, and did not have the energy to walk from the satellite lot. The CNS knew that this could be a problem for other clinic patients and worked with administrators to make sure patients had knowledge of and access to the resources that were needed and available. She understood the clinical implications (patients might experience more complications requiring readmission) and systems implications (e.g., lower quality, increased risks for patients, higher costs, missed appointments) of construction-related, missed appointments for her patient population. APNs who lead patient care teams well and who perform effectively as shuttle diplomats find that their interdisciplinary leadership skills are in demand. Covey (1989) has indicated that he considers interdisciplinary leadership a high-level skill. For example, an APN who was successful in leading a quality improvement (QI) initiative to improve care of asthmatics admitted to the hospital was invited to chair a national task force of health care professionals developing practice guidelines for the treatment of asthma. The ability to provide clinical interdisciplinary leadership requires a firm grasp of clinical and professional issues and differences within nursing while responding to the challenges of other disciplines and the larger society. As APNs gain skill in clinical leadership, they develop the attributes needed to lead in other domains. Mentorship, empowerment, and active participation in organizations are particularly important within the professional domain. First, to be an effective leader, the APN must be able to collaborate with colleagues (see Chapter 12). Second, they must be able to recognize situations in which they themselves need mentoring and in which colleagues can benefit from being mentored and empowered. In the professional domain, APN leaders facilitate the growth of other nurses. Mentoring needs of the APN change over time and more than one mentor may be needed as different aspects of the role are developed. APNs agree that mentorship in professional development is helpful (Doerksen, 2010). Novice or experienced APNs seeking new challenges look for mentors who will foster their professional development. A prospective protégé may recognize and seek an APN’s guidance on clinical or professional development issues. Sometimes, it is the APN who recognizes a potential protégé and offers her or him opportunities to learn and grow. APNs have a responsibility to mentor and prepare the next generation of advanced practice clinicians. Professional leadership begins at the grassroots level and proceeds upward to state, national, and international levels. To acquire leadership skills and experience, it is helpful for novice APNs to become involved in the leadership and committee work of local advanced practice nursing coalitions and organizations and move into state and regional leadership roles as they develop their style and strengths as APN leaders. The ability to place APN leaders in key local, state, and national positions is critical to the visibility and credibility of APNs and to the establishment of their roles within nursing and the larger health care community. In addition to informal leadership development opportunities, there are also formal programs in which APNs can develop the skills to lead in positions such as board membership (Carlson, Klakovich, Broscious, et al., 2011). Systems leadership means leading at the organizational or delivery system level—a skill that requires a multidimensional understanding of systems. Within health care organizations, APNs may lead clinical teams, chair committees, chair or serve as members of boards, manage projects, and direct other initiatives aimed at improving patient care and/or the clinical practice of nurses and other professionals. Systems leadership overlaps the professional domain in situations in which leaders are formally or informally elected or appointed to positions of authority or power within defined organizations and groups. For example, APNs may identify an increase in the rate of patient falls and create a task force to evaluate the problem and design corrective interventions. A critical care CNS or ACNP may initiate interdisciplinary rounds to monitor patients on mechanical ventilation and gather data on clinical variables such as complication rate and time to weaning. APNs may be asked to participate in or lead standing or ad hoc interdisciplinary committees (e.g., medical credentialing, ethics, institutional review board, pharmacy and therapeutics) to ensure that a nursing perspective will be articulated. APNs may be asked by administrators to participate in organizational reengineering or other activities aimed at improving the environment in which nurses practice. APNs, whether in a line or supervisory position, should have the authority to provide systems leadership related to the delivery of clinical care by virtue of their clinical credibility and specific APN job responsibilities. Education strategies for systems leadership are a core responsibility for APN education (Thompson & Nelson-Martin, 2011). Although most APNs will not be entrepreneurs, they need to be aware that the characteristics of successful entrepreneurs are desirable and valued in systems leaders. The term entrepreneurial leadership refers to those leaders who go outside of traditional employment systems to create new opportunities to exercise their special abilities (Shirey, 2004). When these leaders use the entrepreneurial skills of innovation and risk taking, and assume responsibility for achieving specific targets in an organization, they are termed intrapreneurs. Because this leadership style is consistent with the call for health care system redesign, it is worth reviewing characteristics associated with entrepreneurial leadership. Shirey (2007b) has stated that nurse entrepreneurs have a desire to make a difference and see opportunities in situations in which others see barriers or challenges. Blanchard and colleagues (2007) have developed tools for leaders to assess their entrepreneurial strengths and have identified 20 attributes of entrepreneurs (e,g., resourceful, purposeful, risk taker, problem solver, visionary, innovative, communicative, determined). Universities that prepare APNs are offering coursework on innovation, entrepreneurship, and out of the box thinking to prepare entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial APN leaders (Shirey, 2007a). APNs frequently underestimate their transferable skills, which can be used in entrepreneurial or intrapreneurial opportunities (Shirey, 2009). Recognition of those skills will assist the intrapreneurial APN to build a case for how their services can assist the organization in achieving innovative clinical excellence (Shirey, 2007b). Entrepreneurial leadership skills are illustrated in Exemplar 11-1, which also illustrates the evolving nature of the advanced practice nursing leadership competency and how it expands in breadth over time. For more on entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs, see Chapter 19. Although some APNs may not see themselves as being particularly interested in or talented at political advocacy, all APNs have a vested interest in policymaking that affects nursing generally and advanced practice nursing specifically. This domain is becoming increasingly important as more laws and regulations are enacted with implications for APN practice (see Chapters 21 and 22). APNs should be aware of and must often respond to local, state, and national policymaking efforts likely to affect these laws and regulations (Donelan, Buerhaus, DesRoches, et al., 2010; Gilliss, 2011; NACNS, 2011). To be a leader at the level of health policy requires an ability to analyze health care systems, an understanding of the personal qualities associated with effective leadership, and the skill to use these understandings to act strategically. Across these four domains of leadership, APNs use their clinical expertise, team building, and collaborative skills to build community around shared values such as patient-centeredness and commitment to quality. They also build the capability of individuals and systems to respond promptly and efficiently to meet patient needs and improve outcomes (Spross, 2001). The defining characteristics of APN leadership—mentoring and empowerment, innovation and change agency, and activism—may be apparent in all four domains, but the emphasis accorded to each one depends on the particular leadership demands. By outlining these various leadership domains early in the chapter, we want to encourage readers to reflect on the leadership opportunities that they encounter, consider those that align with their clinical interests and personal characteristics, and begin to develop a leadership portfolio. We hope to challenge readers to rethink their ideas about leadership and to integrate a personally meaningful concept of leadership into their identity as an APN. Contemporary definitions of leadership generally fit into one of two categories, transformational (Vance & Larson, 2002) or situational (Grohar-Murray & DiCroce, 1992). Barker (1994) has defined the term transformational leadership as a process whereby “the purposes of the leader and follower become fused, creating unity, wholeness and a collective purpose” (p. 83). Transformational leadership can lead to changes in values, attitudes, perceptions, and/or behaviors on the part of the leader and the follower and lays the groundwork for further positive change. Thus, transformational leadership occurs when people interact in ways that inspire higher levels of motivation and morality among participants. How do leaders do this? Transformational leaders analyze a situation to understand the particular leadership needs and goals; they use this information, together with their interpersonal skills, to motivate, stimulate, share with, conciliate, and satisfy their followers in an interdependent interactional exchange. DePree (1989) has described leadership as an art form that frees (empowers) people “to do what is required of them in the most effective and humane way possible” (p. 1) and contended that contemporary leadership may be viewed simply as a process of moving the self and others toward a shared vision that becomes a shared reality. Successful transformational leadership is relational, driven by a common goal or purpose, and satisfies the needs of leader and follower. It is the leadership style often associated with effective change agents. Schwartz and colleagues (2011) have studied the effects of transformational leadership on the Magnet designation for hospitals. Other authors who have described a transformational approach to leadership include Wang and associates (2012), who studied transformational leadership with Chinese nurses, Heifetz (1994), Secretan (1999, 2003), Senge (2006), and Covey (1989). The term situational leadership is defined as the interaction between an individual’s leadership style and the features of the environment or situation in which he or she is operating. Leadership styles are not fixed and may vary based on the environment. Situational leadership depends on particular circumstances, with leaders and followers assuming interchangeable roles according to environmental demands (Fiedler, Chermers, & Mahar, 1976; Lynch, McCormack, & McCance, 2011; Solman, 2010; Stogdill, 1948). The role of follower is important to any discussion about APN leadership because APNs will find themselves in both roles at a given time. Grohar-Murray and DiCroce (1992) and DePree (1989) enlarged on this idea and used the term roving leadership to describe a participatory process that legitimizes the situational leadership of empowered followers through the support and approval of the hierarchical leader. This notion of leadership is relevant because APNs’ work in collaborative health care teams requires that the roles of leader and follower be interchangeable to meet the complex needs of the patient. • Empowerment of colleagues and followers • Engagement of stakeholders within and outside nursing or one’s agency in the change process • Provision of individual and system support during change initiatives Leadership models that informed this chapter are summarized in Table 11-1. Models are organized by their focus on transformational leadership or change. The many national initiatives calling for system redesign means that change, transformation, and uncertainty are constants. We believe that the models in Table 11-1 have the most promise for helping APNs survive and thrive under these circumstances because individuals and the organizations in which they work are considered. Table 11-1 highlights elements of each model that relate to APN leadership. Readers are encouraged to consult original sources for full descriptions of each model. The Fifth Discipline (Senge, 1990, 2006) includes concepts that will be useful to APNs as they strive to master the APN leadership competency. Whereas certain people may have innate gifts for leadership, others can develop these proficiencies through practice and commitment to the task. To become an effective leader, Senge’s definition implies that one must practice and commit to lifelong learning. In this case, APN leaders are constantly striving to become effective team members who empower others and facilitate change to create effective learning organizations. Senge outlines five disciplines or practices associated with leadership; the framework provides a structure APNs can use to understand leadership and change within complex structures and environments. The five disciplines (Senge, 1990, 2006) are as follows: • Personal mastery. This is the act of continually redefining and clarifying one’s personal vision, refocusing energies, maintaining objectivity, and committing to personal goals and objectives. The importance of personal growth and development is vital to attaining the leadership competency. • Mental models. These are the images that influence how one views the world and attains new insights. Leaders must be aware of their mental models and be willing to examine them and hold them up for inquiry and scrutiny by others. This discipline speaks to the need for clear vision about advanced practice nursing and the ability to defend this viewpoint. • Shared vision. This refers to the leader’s ability to help a team develop and sustain a common image of what the team seeks to create in the future; it is the ability to share a vision with others rather than dictate that vision. The ability to empower others to share the dream and implement change is critical to this discipline. • Team learning. This is the ability to suspend one’s own assumptions, listen to other viewpoints, and genuinely think together. • Systems thinking. This is the fifth discipline, a framework for leadership based on the ability to see the whole picture rather than the isolated parts. It helps us see how our own actions influence what is happening in the larger system (health care). This discipline is an important concept for APNs, who must be able to view advanced practice within the overall context of health care as one member of a team of professionals and patients. Senge and colleagues (1999) have noted that challenges are inherent in the change process, challenges such as delays, competition, and fragmented management that thwarts new productive relationships. By nature, change is dynamic, nonlinear, and characterized by complexity. Senge and colleagues (1999) have defined the term systems citizens as persons who have a perspective and an awareness of the entire world rather than just the local areas in which they live. Catastrophes such as Hurricane Katrina and bridge collapses may not touch us directly, but they do influence our thinking about how to make changes in health care and safety. Unexpected and unplanned events, large and small, can make it difficult to predict the trajectory that a change initiative will take and highlight the importance of a flexible, responsive leadership style. Such a style fosters cohesion, collaboration, and communication among team members, enabling them to approach problem identification and solutions with candor, commitment, and creativity. Stephen Covey’s 1989 best-seller presented personal and interdependent characteristics that foster acquisition of leadership skills. In creating a personal view of leadership, Covey suggested that the most effective way to “keep the end in mind” is to create a personal mission statement that becomes a standard to live by as one progresses to new levels of independence and subsequent interdependence. In Covey’s model, interdependence is achieved only after one has defined and integrated this personal mission or standard into one’s practice. He described attributes of those who lead from a philosophy of interdependence: listening twice as much as you speak, remaining trustworthy by never compromising honesty, maintaining a positive attitude, and keeping a sense of humor. Interdependence allows one to hear and understand the other person’s viewpoint, leading to a synergistic or win-win level of communication. In 2004, Covey expanded on this leadership model by proposing an eighth habit—leaders need to find their voice and help others to find theirs. He noted that leaders at any level can use their inspiration and influence to overcome negativity and use creativity to move the organization to greatness; this type of leader can be a catalyst for change. Covey (2006) developed leadership ideas in light of managing people in the information age. A key concept in this update is that leaders must be aware that the ways in which they lead will influence workers’ choices. He described five choices, ranging from rebel or quit to creative excitement. This can be considered an empowerment model; leadership of knowledge workers “will be characterized by those who find their own voice and who, regardless of their formal position, inspire others to find theirs” (p. 15). Change is a constant in today’s clinical environments. Efforts to transform the health care system are generally focused in three areas, diffusion of innovation, clinician behavior change, and patient behavior change. The reality is that change is messy and not always welcome, even when it seems straightforward. Leaders must be able to stay focused, listen, and manage multiple and changing contingencies. Since the call for redesign and transformation of the health care system, efforts to understand the messiness of systems redesign and transformation have redoubled. For example, an integrative review of diffusion and dissemination of innovations reveals why redesign and transformation are messy—they are exceedingly complex (Greenhalgh, Robert, MacFarlane, et al., 2004)! Nelson and colleagues (2002) have stated that clinical microsystems, defined as the front-line units in which patients and providers interface, are the foundation for providing safe and high-quality care within large organizations. Transforming care at the front-line unit is essential to optimizing care throughout the continuum. They studied the processes and methods of 20 high performing sites and identified nine characteristics that were related to high performance: leadership, organizational culture, macro-organizational support of microsystems, patient focus, staff focus, interdependence of the care team, information and IT, performance improvement, and performance patterns. Massoud and colleagues (2006) have developed a model for IHI to address the difficulty in spreading effective innovation beyond the immediate environment. With today’s imperative to implement best practices throughout health care, diffusion within and among health care organizations is key. Founded on Everett Rogers’ definition of diffusion, this framework for spread is based on four main components—preparing for spread, establishing an aim for spread, developing an initial spread plan, and executing or refining the spread plan. Leadership is essential in preparing a plan to spread innovation. As a leader, the APN must take an active role, beginning with the preparation phase and continuing throughout implementation and maintenance of the plan. Identifying the target population, improvements to be made, and target time frame is the focus of establishing the aim. During the development of the spread plan, the leader oversees the project and may take an active role in developing the plan. Finally, the APN leader needs to ensure collection and use of feedback and data about the effectiveness of the plan, supporting course correction as needed. IHI has provided an example of improved waiting times in 1800 Veterans Affairs outpatient clinics by using the spread of innovation model (Massoud, Nielsen, Nolan, et al., 2006). Leaders in this project were enthusiastic about improving access for patients, ensuring adequate resources, providing incentives, and closely tracking the outcomes of the spread (Massoud et al., 2006). APNs are particularly well prepared as leaders to promote the spread of innovative best practices in health care. Appreciative inquiry (AI) is a leadership model that is predicated on the focus of seeking positives through appreciative conversations and relationship building (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, 2008). Rather than focusing on a problem, the model encourages a focus on what is working well and what the organization does well, and builds on this. When we expand what we do best, problems seem to fall away or are outgrown. Leading through positive interactions results in people working together toward a shared vision and preferred future, without the burden of being weighed down by problems. Leaders using this leadership model are open to inquiry without having a preconceived outcome in mind; rather, they facilitate a search for shared meaning and build and expand on what is working well. For example, faculty at a graduate program for APNs wanted to create a DNP program, but there were quality concerns about some of their existing MSN programs. Through an AI process, the faculty decided to build a DNP program based solely on the certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) role, because that was their strongest program. Moreover, through this process, they decided to phase out two of their Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) programs because they were not up to the same level of quality. Over time, the CRNA program was recognized as one of the nation’s top programs. So, rather than investing solely on fixing what’s broken, the appreciative inquiry model directs resources and visioning to an organization’s greatest strengths. This leadership model uses a 4D cycle: • Discovery—an exploration of what is; finding organizational strengths and processes that work well • Dream—imagining what could be; envisioning innovations that would work even better for the organization’s future • Design—determining what should be; planning and prioritizing those processes AI uses a positive perspective that can be motivational and inspirational for employees with the goal of increasing exceptional performance. This model can work well for the APN who is skilled in developing partnerships, which can be symbiotic in this model building in regard to the ideas and innovations of each partner to solve problems in the complex health care environment (Sherwood, 2006). Although evidence for the effectiveness of this leadership model is low level and primarily anecdotal, there is enough evidence to support further rigorous research (Jones, 2010). The consequences of leading with an emphasis on defects are that it lacks vision, places attention to yesterday’s causes, and can lead to narrow and fragmented solutions. The AI model shifts from asking “What is the biggest problem?” to “What possibilities exist that we have not yet considered?” This approach quickly leads individuals to a shared purpose and vision. Recent studies are all informative in our use of the AI model, including one by Rapede (2011), who used a model of participatory dreaming and journaling to understand the life struggles of women abused as children, one by Richer and associates (2009), who used case study research to look at the reorganization of health care services, and one by Smythe and coworkers (2009), who researched optimal service in a rural primary birthing center. In this section, change is used to refer to any of the various types of initiatives aimed at improving the quality and safety of practice, whether by revising policies or helping clinicians master new knowledge and change behavior. In other words, change is seen as any clinical or systems effort to encourage the adoption and diffusion of innovation, including but not limited to quality improvement, product rollouts, clinician education, and skill development. Change does not have a discrete beginning and end but, instead, appears to be a series of continuous transitions that overlap one another. Because of this, change agency must be woven into the fabric of an APN’s everyday life and work. As with patient assessment to effect individual behavior change, APNs must be skilled at assessing and reassessing their organizations and the complex forces that drive the health care system to be effective change agents. Systems innovation requires leadership that is continuous and flexible and demands ongoing attention to and redefinition of appropriate strategies (Greenhalgh et al., 2004; Klein, Gabelnick, & Herr, 1998; Massoud et al., 2006; Thompson & Nelson-Martin, 2011). One specific change strategy associated with leading a change initiative is opinion leadership (Greenhalgh et al., 2004; Locock, Dopson, Chambers, et al., 2001; Oxman, Thomson, Davis, et al., 1995; Soumerai et al., 1998; Thomson et al., 1999). Opinion leaders are clinicians who are identified by their colleagues as likeable, trustworthy, and influential (Doumit, Gattellari, Grimshaw, et al., 2007; Oxman et al., 1995) A clinician is likely to listen to the opinion leader and might make a change in practice based on what he or she has learned from the opinion leader. The role of an opinion leader parallels that of the maven described by Gladwell (2000). One study of opinion leaders in several different clinical settings has indicated that contextual factors influenced the ability of an opinion leader to promote guideline adoption by colleagues (Locock et al., 2001). Shirey (2008) has stated that “opinion leaders must not only be knowledgeable, respected, trusted, and well-connected within the organization, they must also be generous with their time and giving of their expertise.” As APNs become recognized for their accurate clinical decision making, they become opinion leaders. They are sought out by others and, when the APN speaks, others listen. Thus, a staff nurse may ask a CNS to look at a wound and advise, or an NP returns to her practice from a conference and, when she shares what she has learned, colleagues are eager to try the new information. This finding suggests the importance of attending to environmental cues when change is planned. Although studies of opinion leaders have been done, findings about their effectiveness are mixed, in part because the activities of opinion leaders have not been well described (Oxman et al., 1995). Driving and restraining forces are useful concepts for APNs as they plan for change and evaluate both planned and unplanned changes. For example, as APNs extend their practices across state lines, the movement toward multistate licensure is gaining momentum (Young et al., 2012; see Chapter 12, Fig. 12-1, for an illustration of driving and restraining forces). Depending on existing policies and procedures for reimbursement and prescriptive authority within states, these forces can serve as driving or restraining influences for APNs. As multistate licensure for APNs evolves, telehealth may be considered a driving force and states’ rights may be a restraining force. Driving and restraining forces are also useful for analyzing the organizational settings in which APNs work. For example, an organizational assessment of these various forces is useful in determining an institution’s level of commitment to diversity. At times, physicians have been perceived as restraining forces for change. Experienced APNs know that one of the challenges in system redesign and transformation has been engaging physicians in the work of improving quality as a team member rather than in a silo (Shortell & Singer, 2008). Physicians themselves have begun to recognize this and have made specific recommendations that administrators and APNs can use for engaging physicians in this important work (Reinertsen, Gosfield, Rupp, et al., 2007). For example, physicians and APNs together can request support through workshops and on-site experts in making a major institutional change, such as implementation of electronic medical records. A major concern for health care stakeholders at all levels is the rapidity with which change is occurring in the health care field. Even when one develops detailed plans for a change, events may occur that reshape process and progress so that what gets implemented may not be exactly the same as the original proposal. As the rapidity of change increases, the time frame to accomplish change strategies shortens. This phenomenon makes change more difficult for individuals and organizations to manage. As a consequence, many of the traditional models still being used to implement change will not work. Planned versus unplanned change is based predominantly on issues of time (Senge, 2006)—time to plan for and think through the desired change, time to orient and allow stakeholders to become comfortable with change, and time to educate and allow the change process to occur. In most health care systems, people perceive a poverty of time; this barrier requires creativity to transcend. O’Connell (1999) has questioned whether health care organizations can sustain fast-paced change unless a “culture of change” is in place that assists and supports adaptation to new systems and ways of knowing and doing. A culture of change requires several components, including learning about change and change strategies, encouraging dialogue, valuing collaboration, and being committed to enacting change. O’Connell proposed the following strategies for promoting a culture of change within an organization: • Maintain momentum toward change. • Emphasize managerial support in the process of changing work flow and practice patterns. • Encourage the question “why” and exercise tolerance for the results. • Emphasize the importance of personal concerns and address them. • Find new and different ways to demonstrate administrative support.

Leadership

Context in Which Advanced Practice Nurses Exercise Leadership Competency

Health Care System Transformation

Redesign of Health Professional Education

Interdisciplinary Competencies

Advanced Practice Nurse Competencies

Leadership Domains of Advanced Practice Nurses

Clinical Leadership

Professional Leadership

Systems Leadership

Health Policy Leadership

Leadership: Definitions, Models, and Concepts

Definitions of Leadership

Leadership Models That Lead to Transformation

The Fifth Discipline

The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People

Leadership Models That Address Systems Change and Innovation

Microsystems in Health Care: High-Performing Clinical Units

Spread of Innovation

Appreciative Inquiry

Concepts Related to Change

Opinion Leadership

Driving and Restraining Forces

Pace of Change

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Leadership

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access