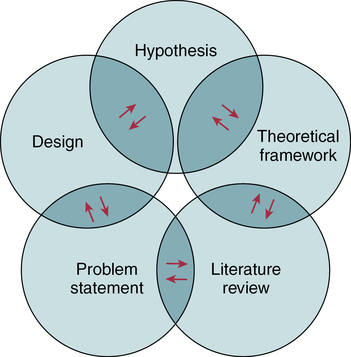

CHAPTER 8 After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: • Identify the purpose of research design. • Define control and fidelity as it affects research design and the outcomes of a study. • Compare and contrast the elements that affect fidelity and control. • Begin to evaluate what degree of control should be exercised in a study. • Identify the threats to internal validity. • Identify the conditions that affect external validity. • Identify the links between study design and evidence-based practice. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critiquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. The word design implies the organization of elements into a masterful work of art. In the world of art and fashion, design conjures up images that are used to express a total concept. When an individual creates a structure such as a dress pattern or blueprints for the design of a house, the type of structure depends on the aims of the creator. The same can be said of the research process. The research process does not need to be a sterile procedure, but one where the researcher develops a masterful work within the limits of a research question or hypothesis and the related theoretical basis. The framework that the researcher creates is the design. When reading a study, you should be able to recognize that the research question, purpose, literature review, theoretical framework, and hypothesis all interrelate with, complement, and assist in the operationalization of the design (Figure 8-1). The degree to which there is a fit between these elements and the steps of the research process strengthens the study and also your confidence in the evidence provided by the findings and their potential applicability to practice. For you to understand the implications and usefulness of a study for evidence-based practice, the key issues of research design must be understood. This chapter provides an overview of the meaning, purpose, and issues related to quantitative research design, and Chapters 9 and 10 present specific types of quantitative designs. The research design in quantitative research has overlapping yet unique purposes. The design • Provides the plan or blueprint • Is the vehicle for systematically testing research questions and hypotheses • Provides the structure for maintaining the control in the study A research example that demonstrates how the design can aid in the solution of a research question and maintain control is the study by Thomas and colleagues (2012; see Appendix A), whose aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of education, motivational-interviewing–based coaching and usual care on the improvement of cancer pain management. Subjects who fit the study’s inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to one of the three groups. The interventions were clearly defined. The authors also discuss how they maintained intervention fidelity or constancy of interventionists, data-collector training and supervision, and follow-up throughout the study. By establishing the specific sample criteria and subject eligibility (inclusion criteria; see Chapter 12) and by clearly describing and designing the experimental intervention, the researchers demonstrated that they had a well-developed plan and structure and were able to consistently maintain the study’s conditions. A variety of considerations, including the type of design chosen, affect a study’s successful completion. These considerations include the following: • Objectivity in conceptualizing the research question or hypothesis • Control and intervention fidelity The next two chapters present different experimental, quasi-experimental, and nonexperimental designs. As you will recall from Chapter 1, a study’s type of design is linked to the level of evidence. As you critically appraise the design, you must also take into account other aspects of a study’s design and conduct. These aspects are reviewed in this chapter. How they are applied depends on the type of design (see Chapters 9 and 10). Objectivity in the conceptualization of the research question is derived from a review of the literature and development of a theoretical framework (see Figure 8-1). Using the literature, the researcher assesses the depth and breadth of available knowledge on the question. The literature review and theoretical framework should demonstrate that the researcher reviewed the literature critically and objectively (see Chapters 3 and 4) because this affects the design chosen. For example, a research question about the length of a breast-feeding teaching program in relation to adherence to breast-feeding may suggest either a correlational or an experimental design (see Chapters 9 and 10), whereas a question related to fatigue levels and amount of sleep at different points in cancer treatment may suggest a survey or correlational study (see Chapter 10). Therefore the literature review should reflect the following: • When the question was studied • What aspects of the question were studied • Where it was investigated and with what populations Accuracy in determining the appropriate design is also accomplished through the theoretical framework and literature review (see Chapters 3 and 4). Accuracy means that all aspects of a study systematically and logically follow from the research question or hypothesis. The simplicity of a research project does not render it useless or of less value. If the scope of a study is limited or focused, the researchers should demonstrate how accuracy was maintained. You should feel that the researcher chose a design that was consistent with the question and offered the maximum amount of control. The issues of control are discussed later in this chapter. Also, many research questions have not yet been researched. Therefore a preliminary or pilot study is also a wise approach. A pilot study can be thought of as a beginning study in an area conducted to test and refine a study’s data collection methods, and it helps to determine the sample size needed for a larger study. For example, Crane-Okada and colleagues (2012) published a report of their study which pilot tested the feasibility of the short-term effects of a 12-week Mindful Movement Program intervention for women age 50 years and older. The key is the accuracy, validity, and objectivity used by the researcher in attempting to answer the question. Accordingly, when reading research you should read various types of studies and assess how and if the criteria for each step of the research process were followed. Many journals publish not only randomized controlled studies (see Chapter 9), but also pilot studies. When critiquing the research design, one also needs to be aware of the pragmatic consideration of feasibility. Sometimes feasibility issues do not truly sink in until one does research. It is important to consider feasibility when reviewing a study, including subject availability, time required for subjects to participate, costs, and data analysis (Table 8-1). TABLE 8-1 PRAGMATIC CONSIDERATIONS IN DETERMINING THE FEASIBILITY OF A RESEARCH QUESTION A researcher chooses a design to maximize the degree of control, fidelity or uniformity over the tested variables. Control is maximized by a well-planned study that considers each step of the research process and the potential threats to internal and external validity. In a study that tests interventions (randomized controlled trial; see Chapter 9), intervention fidelity (also referred to as treatment fidelity) is a key concept. Fidelity means trustworthiness or faithfulness. In a study, intervention fidelity means that the researcher actively standardized the intervention and planned how to administer the intervention to each subject in the same manner under the same conditions. An efficient design can maximize results, decrease bias, and control preexisting conditions that may affect outcomes. To accomplish these tasks, the research design and methods should demonstrate the researcher’s efforts to maintain fidelity. Control is important in all designs. But the elements of control and fidelity differ based on the type of design. Thus, when various research designs are critiqued, the issue of control is always raised but with varying levels of flexibility. The issues discussed here will become clearer as you review the various designs types discussed in later chapters (see Chapters 9 and 10). Control is accomplished by ruling out extraneous or mediating variables that compete with the independent variables as an explanation for a study’s outcome. An intervening, extraneous, or mediating variable is one that interferes with the operations of the variables being studied. An example would be the type of breast cancer treatment patients experienced (Thomas et al., 2012). Means of controlling extraneous variables include the following: • Use of consistent data-collection procedures • Training and supervision of data collectors and interventionists • Manipulation of the independent variable In a stop-smoking study, extraneous variables may affect the dependent (outcome) variable. The characteristics of a study’s subjects are common extraneous variables. Age, gender, length of time smoked, amount smoked, and even smoking rules may affect the outcome in the stop-smoking example. These variables may therefore affect the outcome, even though they are extraneous or outside of the study’s design. As a control for these and other similar problems, the researcher’s subjects should demonstrate homogeneity or similarity with respect to the extraneous variables relevant to the particular study (see Chapter 12). Extraneous variables are not fixed but must be reviewed and decided on, based on the study’s purpose and theoretical base. By using a sample of homogeneous subjects, based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, the researcher has used a straightforward step of control. For example, in the study by Alhusen and colleagues (2012; see Appendix B), the researchers ensured homogeneity of the sample based on age and demographics. This step limits the generalizability or application of the outcomes to other populations when analyzing and discussing the outcomes (see Chapter 17). As you read studies, you will often see the researchers limit the generalizability of the findings to like samples. Results can then be generalized only to a similar population of individuals. You may say that this is limiting. This is not necessarily so because no treatment or program can be applicable to all populations, nor is it feasible to examine a large number of different populations in one study. Thus as you appraise the findings of studies, you must take the differences in populations into consideration.

Introduction to quantitative research

Purpose of research design

Objectivity in the research question conceptualization

Accuracy

Feasibility

FACTOR

PRAGMATIC CONSIDERATIONS

Time

The research question must be one that can be studied within a realistic period. All research has completion deadlines. A study must be well circumscribed to provide ample completion time.

Subject Availability

A researcher must determine whether a sufficient number of subjects will be available and willing to participate. If one has a captive audience (e.g., students in a classroom), it may be relatively easy to enlist subjects. If a study involves subjects’ independent time and effort, they may be unwilling to participate when there is no apparent reward. Potential subjects may have fears about harm or confidentiality and be suspicious of the research process. Subjects with unusual characteristics may be difficult to locate. People are generally cooperative about participating, but a researcher should consider enlisting more subjects than actually needed to prepare for subject attrition. At times, a research report may note how the inclusion criteria were liberalized or the number of subjects altered, as a result of some unforeseen recruitment or attrition consideration.

Facility and Equipment Availability

All research requires some equipment such as questionnaires, telephones, computers, or other apparatus. Most research requires availability of some facility type for data collection (e.g., a hospital unit or laboratory space).

Money

Research requires expenditure of money. Before starting a study the researcher itemizes expenses and projects the total study costs. A budget provides a picture of the monetary needs for items such as books, postage, printing, technical equipment, computer charges, and salaries. Expenses can range from about $1,000 for a small-scale project to hundreds of thousands of dollars per year for a large federally funded project.

Researcher Experience

Selection of a research problem should be based on the nurse’s experience and knowledge because it is more prudent to develop a study related to a topic that is theoretically or experientially familiar.

Ethics

Research that place unethical demands on subjects may not be feasible for study. Researchers take ethical considerations seriously. Ethics considerations affect the design and methodology choice.

Control and intervention fidelity

Homogeneous sampling

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Introduction to quantitative research

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access