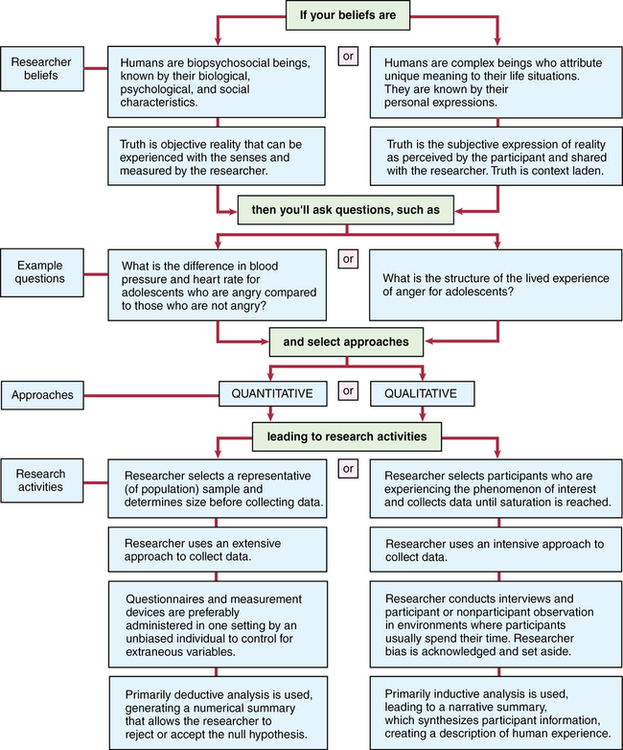

CHAPTER 5 After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following: • Describe the components of a qualitative research report. • Describe the beliefs generally held by qualitative researchers. • Identify four ways qualitative findings can be used in evidence-based practice. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critiquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. Qualitative research is discovery oriented; that is, it is explanatory, descriptive, and inductive in nature. It uses words, as opposed to numbers, to explain a phenomenon. Qualitative research lets us see the world through the eyes of another—the woman who struggles to take her antiretroviral medication, or the woman who has carefully thought through what it might be like to have a baby despite a debilitating illness. Qualitative researchers assume that we can only understand these things if we consider the context in which they take place, and this is why most qualitative research takes place in naturalistic settings. Qualitative studies make the world of an individual visible to the rest of us. Qualitative research involves an “interpretative, naturalistic approach to the world; meaning that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of or interpret phenomena in terms of the meaning people bring to them” (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011, p. 3). Qualitative researchers believe that there are multiple realities that can be understood by carefully studying what people can tell us or what we can observe as we spend time with them. For example, the experience of having a baby, while it has some shared characteristics, is not the same for any two women, and is definitely different for a disabled mother. Thus, qualitative researchers believe that reality is socially constructed and context dependent. Even the experience of reading this book is different for any two students; one may be completely engrossed by the content, while another is reading, but is worrying about whether or not her financial aid will be approved soon (Fig. 5-1). Because qualitative researchers believe that the discovery of meaning is the basis for knowledge, their research questions, approaches, and activities are often quite different from quantitative researchers (see the Critical Thinking Decision Path). Qualitative researchers, for example, seek to understand the “lived experience” of the research participants. They might use interviews or observations to gather new data, and use new data to create narratives about research phenomena. Thus, qualitative researchers know that there is a very strong imperative to clearly describe the phenomenon under study. Ideally, the reader of a qualitative research report, if even slightly acquainted with the phenomenon, would have an “aha!” moment in reading a well-written qualitative report. The components of a qualitative research study include the review of literature, study design, study setting and sample, approaches for data collection and analysis, study findings, and conclusions with implications for practice and research. As we reflect on these parts of qualitative studies, we will see how nurses use the qualitative research process to develop new knowledge for practice (Box 5-1). The study design is a description of how the qualitative researcher plans to go about answering the research questions. In qualitative research, there may simply be a descriptive or naturalistic design in which the researchers adhere to the general tenets of qualitative research, but do not commit to a particular methodology. There are many different qualitative methods used to answer the research questions. Some of these methods will be discussed in the next chapter. What is important, as you read from this point forward, is that the study design must be congruent with the philosophical beliefs that qualitative researchers hold. You would not expect to see a qualitative researcher use methods common to quantitative studies, such as a random sample or battery of questionnaires administered in a hospital outpatient clinic or a multiple regression analysis. Rather, you would expect to see a design that includes participant interviews or observation, strategies for inductive analysis, and plans for using data to develop narrative summaries with rich description of the details from participants’ experiences (see Fig. 5-1). You may also read about a pilot study in the description of a study design; this is work the researchers did before undertaking the main study to make sure that the logistics of the proposed study were reasonable. For example, pilot data may describe whether the investigators were able to recruit participants and whether the research design led them to information they needed. The study sample refers to the group of people that the researcher will interview or observe in the process of collecting data to answer the research questions. In most qualitative studies, the researchers are looking for a purposeful or purposively selected sample (see Chapter 10). This means that they are searching for a particular kind of person who can illuminate the phenomenon they want to study. For example, the researchers may want to interview women with multiple sclerosis, or rheumatoid arthritis. There may be other parameters—called inclusion and exclusion criteria—that the researchers impose as well, such as requiring that participants be older than 18 years, or not using illicit drugs, or deciding about a first pregnancy (as opposed to subsequent pregnancies). When researchers are clear about these criteria, they are able to identify and recruit study participants with experiences needed to shed light on the phenomenon in question. Often the researchers make decisions such as determining who might be a “long-term survivor” of a certain illness. In this case, they must clearly understand why and how they decided who would fit into this category. Is a long-term survivor someone who has had an illness for 5 years? Ten years? What is the median survival time for people with this diagnosis? Thus, as a reader of nursing research, you are looking for evidence of sound scientific reasoning behind the sampling plan.

Introduction to qualitative research

What is qualitative research?

What do qualitative researchers believe?

Components of a qualitative research study

Study design

Sample

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Introduction to qualitative research

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access