Understand why research is important in nursing

Discuss the need for evidence-based practice

Discuss the need for evidence-based practice

Describe broad historical trends and future directions in nursing research

Describe broad historical trends and future directions in nursing research

Identify alternative sources of evidence for nursing practice

Identify alternative sources of evidence for nursing practice

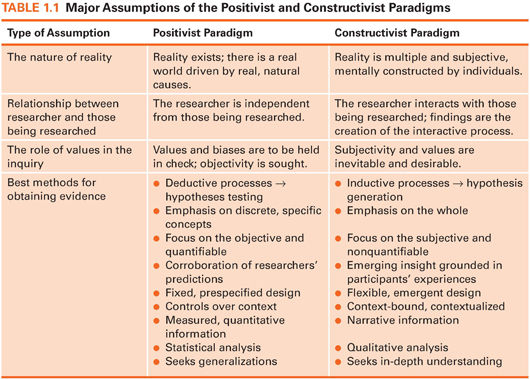

Describe major characteristics of the positivist and constructivist paradigm

Describe major characteristics of the positivist and constructivist paradigm

Compare the traditional scientific method (quantitative research) with constructivist methods (qualitative research)

Compare the traditional scientific method (quantitative research) with constructivist methods (qualitative research)

Identify several purposes of quantitative and qualitative research

Identify several purposes of quantitative and qualitative research

Define new terms in the chapter

Define new terms in the chapter

Key Terms

Assumption

Assumption

Cause-probing research

Cause-probing research

Clinical nursing research

Clinical nursing research

Clinical significance

Clinical significance

Constructivist paradigm

Constructivist paradigm

Empirical evidence

Empirical evidence

Evidence-based practice (EBP)

Evidence-based practice (EBP)

Generalizability

Generalizability

Journal club

Journal club

Nursing research

Nursing research

Paradigm

Paradigm

Positivist paradigm

Positivist paradigm

Qualitative research

Qualitative research

Quantitative research

Quantitative research

Research

Research

Research methods

Research methods

Scientific method

Scientific method

Systematic review

Systematic review

NURSING RESEARCH IN PERSPECTIVE

We know that many of you readers are not taking this course because you plan to become nurse researchers. Yet, we are also confident that many of you will participate in research-related activities during your careers, and virtually all of you will be expected to be research-savvy at a basic level. Although you may not yet grasp the relevance of research in your career as a nurse, we hope that you will come to see the value of nursing research during this course and will be inspired by the efforts of the thousands of nurse researchers now working worldwide to improve patient care. You are embarking on a lifelong journey in which research will play a role. We hope to prepare you to enjoy the voyage.

What Is Nursing Research?

Whether you know it or not, you have already done a lot of research. When you use the Internet to find the “best deal” on a laptop or an airfare, you start with a question (e.g., Who has the best deal for what I want?), collect the information by searching different websites, and then come to a conclusion. This “everyday research” has much in common with formal research—but, of course, there are important differences, too.

As a formal enterprise, research is systematic inquiry that uses disciplined methods to answer questions and solve problems. The ultimate goal of formal research is to gain knowledge that would be useful for many people. Nursing research is systematic inquiry designed to develop trustworthy evidence about issues of importance to nurses and their clients. In this book, we emphasize clinical nursing research, which is research designed to guide nursing practice. Clinical nursing research typically begins with questions stemming from practice problems—problems you may have already encountered.

Examples of nursing research questions

Does a text message notification process help to reduce follow-up time for women with abnormal mammograms? (Oakley-Girvan et al., 2016)

Does a text message notification process help to reduce follow-up time for women with abnormal mammograms? (Oakley-Girvan et al., 2016)

What are the daily experiences of patients receiving hemodialysis treatment for end-stage renal disease? (Chiaranai, 2016)

What are the daily experiences of patients receiving hemodialysis treatment for end-stage renal disease? (Chiaranai, 2016)

| TIP You may have the impression that research is abstract and irrelevant to practicing nurses. But nursing research is about real people with real problems, and studying those problems offers opportunities to solve or address them through improvements to nursing care. |

The Importance of Research to Evidence-Based Nursing

Nursing has experienced profound changes in the past few decades. Nurses are increasingly expected to understand and undertake research and to base their practice on evidence from research—that is, to adopt an evidence-based practice (EBP). EBP, broadly defined, is the use of the best evidence in making patient care decisions. Such evidence typically comes from research conducted by nurses and other health care professionals. Nurse leaders recognize the need to base specific nursing decisions on evidence indicating that the decisions are clinically appropriate and cost-effective and result in positive client outcomes.

In some countries, research plays an important role in nursing credentialing and status. For example, the American Nurses Credentialing Center—an arm of the American Nurses Association—has developed a Magnet Recognition Program to recognize health care organizations that provide high-quality nursing care. To achieve Magnet status, practice environments must demonstrate a sustained commitment to EBP and nursing research. Changes to nursing practice are happening every day because of EBP efforts.

Example of evidence-based practice

Many clinical practice changes reflect the impact of research. For example, “kangaroo care,” the holding of diaper-clad preterm infants skin-to-skin, chest-to-chest by parents, is now widely practiced in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), but in the early 1990s, only a minority of NICUs offered kangaroo care options. The adoption of this practice reflects good evidence that early skin-to-skin contact has clinical benefits and no negative side effects (Ludington-Hoe, 2011; Moore et al., 2012). Some of this evidence comes from rigorous studies by nurse researchers (e.g., Campbell-Yeo et al., 2013; Cong et al., 2009; Cong et al., 2011; Holditch-Davis et al., 2014; Lowson et al., 2015).

Roles of Nurses in Research

In the current EBP environment, every nurse is likely to engage in one or more activities along a continuum of research participation. At one end of the continuum are users or consumers of nursing research—nurses who read research reports to keep up-to-date on findings that may affect their practice. EBP depends on well-informed nursing research consumers.

At the other end of the continuum are the producers of nursing research: nurses who actively design and undertake studies. At one time, most nurse researchers were academics who taught in schools of nursing, but research is increasingly being conducted by practicing nurses who want to find what works best for their clients.

Between these two end points on the continuum lie a variety of research activities in which nurses engage. Even if you never conduct a study, you may do one of the following:

1. Contribute an idea for a clinical inquiry

2. Assist in collecting research information

3. Offer advice to clients about participating in a study

4. Search for research evidence

5. Discuss the implications of a study in a journal club in your practice setting, which involves meetings to discuss research articles

In all research-related activities, nurses who have some research skills are better able than those without them to contribute to nursing and to EBP. Thus, with the research skills you gain from this book, you will be prepared to contribute to the advancement of nursing.

Nursing Research: Past and Present

Most people agree that research in nursing began with Florence Nightingale in the mid-19th century. Based on her skillful analysis of factors affecting soldier mortality and morbidity during the Crimean War, she was successful in bringing about changes in nursing care and in public health. For many years after Nightingale’s work, however, research was absent from the nursing literature. Studies began to appear in the early 1900s but most concerned nurses’ education.

In the 1950s, nursing research began to flourish. An increase in the number of nurses with advanced skills and degrees, an increase in the availability of research funding, and the establishment of the journal Nursing Research helped to propel nursing research. During the 1960s, practice-oriented research began to emerge, and research-oriented journals started publication in several countries. During the 1970s, there was a change in research emphasis from areas such as teaching and nurses’ characteristics to improvements in client care. Nurses also began to pay attention to the utilization of research findings in nursing practice.

The 1980s brought nursing research to a new level of development. Of particular importance in the United States was the establishment in 1986 of the National Center for Nursing Research (NCNR) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The purpose of NCNR was to promote and financially support research projects and training relating to patient care. Nursing research was strengthened and given more visibility when NCNR was promoted to full institute status within the NIH: In 1993, the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) was established. The birth and expansion of NINR helped put nursing research more into the mainstream of research activities enjoyed by other health disciplines. Funding opportunities expanded in other countries as well.

The 1990s witnessed the birth of several more journals for nurse researchers, and specialty journals increasingly came to publish research articles. International cooperation in integrating EBP into nursing also began to develop in the 1990s. For example, Sigma Theta Tau International sponsored the first international research utilization conference, in cooperation with the faculty of the University of Toronto, in 1998.

| TIP For those interested in learning more about the history of nursing research, we offer an expanded summary in the Supplement to this chapter on |

Future Directions for Nursing Research

Nursing research continues to develop at a rapid pace and will undoubtedly flourish in the 21st century. In 1986, NCNR had a budget of $16 million, whereas NINR funding in fiscal year 2016 was just under $150 million. Among the trends we foresee for the near future are the following:

Continued focus on EBP. Encouragement for nurses to use research findings in practice is sure to continue. This means that improvements will be needed in the quality of nursing studies and in nurses’ skills in locating, understanding, critiquing, and using relevant study results. Relatedly, there is an emerging interest in translational research—research on how findings from studies can best be translated into practice.

Continued focus on EBP. Encouragement for nurses to use research findings in practice is sure to continue. This means that improvements will be needed in the quality of nursing studies and in nurses’ skills in locating, understanding, critiquing, and using relevant study results. Relatedly, there is an emerging interest in translational research—research on how findings from studies can best be translated into practice.

Stronger evidence through confirmatory strategies. Practicing nurses rarely adopt an innovation on the basis of poorly designed or isolated studies. Strong research designs are essential, and confirmation is usually needed through replication (i.e., repeating) of studies in different clinical settings to ensure that the findings are robust.

Stronger evidence through confirmatory strategies. Practicing nurses rarely adopt an innovation on the basis of poorly designed or isolated studies. Strong research designs are essential, and confirmation is usually needed through replication (i.e., repeating) of studies in different clinical settings to ensure that the findings are robust.

Continued emphasis on systematic reviews. Systematic reviews are a cornerstone of EBP and have assumed increasing importance in all health disciplines. Systematic reviews rigorously integrate research information on a topic so that conclusions about the state of evidence can be reached.

Continued emphasis on systematic reviews. Systematic reviews are a cornerstone of EBP and have assumed increasing importance in all health disciplines. Systematic reviews rigorously integrate research information on a topic so that conclusions about the state of evidence can be reached.

Expanded local research in health care settings. Small studies designed to solve local problems will likely increase. This trend will be reinforced as more hospitals apply for (and are recertified for) Magnet status in the United States and in other countries.

Expanded local research in health care settings. Small studies designed to solve local problems will likely increase. This trend will be reinforced as more hospitals apply for (and are recertified for) Magnet status in the United States and in other countries.

Expanded dissemination of research findings. The Internet and other technological advances have had a big impact on the dissemination of research information, which in turn helps to promote EBP.

Expanded dissemination of research findings. The Internet and other technological advances have had a big impact on the dissemination of research information, which in turn helps to promote EBP.

Increased focus on cultural issues and health disparities. The issue of health disparities has emerged as a central concern, and this in turn has raised consciousness about the cultural sensitivity of health interventions. Research must be sensitive to the beliefs, behaviors, epidemiology, and values of culturally and linguistically diverse populations.

Increased focus on cultural issues and health disparities. The issue of health disparities has emerged as a central concern, and this in turn has raised consciousness about the cultural sensitivity of health interventions. Research must be sensitive to the beliefs, behaviors, epidemiology, and values of culturally and linguistically diverse populations.

Clinical significance and patient input. Research findings increasingly must meet the test of being clinically significant, and patients have taken center stage in efforts to define clinical significance. A major challenge in the years ahead will involve incorporating both research evidence and patient preferences into clinical decisions.

Clinical significance and patient input. Research findings increasingly must meet the test of being clinically significant, and patients have taken center stage in efforts to define clinical significance. A major challenge in the years ahead will involve incorporating both research evidence and patient preferences into clinical decisions.

What are nurse researchers likely to be studying in the future? Although there is tremendous diversity in research interests, research priorities have been articulated by NINR, Sigma Theta Tau International, and other nursing organizations. For example, NINR’s Strategic Plan, launched in 2011 and updated in 2013, described five areas of focus: promoting health and preventing disease, symptom management and self-management, end-of-life and palliative care, innovation, and the development of nurse scientists (http://www.ninr.nih.gov).

| TIP All websites cited in this chapter, plus additional websites with useful content relating to the foundations of nursing research, are in the Internet Resources on |

SOURCES OF EVIDENCE FOR NURSING PRACTICE

Nurses make clinical decisions based on a large repertoire of knowledge. As a nursing student, you are gaining skills on how to practice nursing from your instructors, textbooks, and clinical placements. When you become a registered nurse (RN), you will continue to learn from other nurses and health care professionals. Because evidence is constantly evolving, learning about best-practice nursing will carry on throughout your career.

Some of what you have learned thus far is based on systematic research, but much of it is not. What are the sources of evidence for nursing practice? Where does knowledge for practice come from? Until fairly recently, knowledge primarily was handed down from one generation to the next based on clinical experience, trial and error, tradition, and expert opinion. These alternative sources of knowledge are different from research-based information.

Tradition and Authority

Some nursing interventions are based on untested traditions, customs, and “unit culture” rather than on sound evidence. Indeed, a recent analysis suggests that some “sacred cows” (ineffective traditional habits) persist even in a health care center recognized as a leader in EBP (Hanrahan et al., 2015). Another common source of knowledge is an authority, a person with specialized expertise. Reliance on authorities (such as nursing faculty or textbook authors) is unavoidable. Authorities, however, are not infallible—particularly if their expertise is based primarily on personal experience; yet, their knowledge is often unchallenged.

Example of “myths” in nursing textbooks

One study suggests that nursing textbooks may contain many “myths.” In their analysis of 23 widely used undergraduate psychiatric nursing textbooks, Holman and colleagues (2010) found that all books contained at least one unsupported assumption (myth) about loss and grief—i.e., assumptions not supported by current research evidence. And many evidence-based findings about grief and loss failed to be included in the textbooks.

| TIP The consequences of not using research-based evidence can be devastating. For example, from 1956 through the 1980s, Dr. Benjamin Spock published several editions of Baby and Child Care, a parental guide that sold over 19 million copies worldwide. As an authority figure, he wrote the following advice: “I think it is preferable to accustom a baby to sleeping on his stomach from the beginning if he is willing” (Spock, 1979, p. 164). Research has clearly demonstrated that this sleeping position is associated with heighted risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In their systematic review of evidence, Gilbert and colleagues (2005) wrote, “Advice to put infants to sleep on the front for nearly half a century was contrary to evidence from 1970 that this was likely to be harmful” (p. 874). They estimated that if medical advice had been guided by research evidence, over 60,000 infant deaths might have been prevented. |

Clinical Experience and Trial and Error

Clinical experience is a functional source of knowledge. Yet, personal experience has limitations as a source of evidence for practice because each nurse’s experience is too narrow to be generally useful, and personal experiences are often colored by biases. Trial and error involves trying alternatives successively until a solution to a problem is found. Trial and error can be practical, but the method tends to be haphazard, and solutions may be idiosyncratic.

Assembled Information

In making clinical decisions, health care professionals also rely on information that has been assembled for various purposes. For example, local, national, and international benchmarking data provide information on such issues as the rates of using various procedures (e.g., rates of cesarean deliveries) or rates of clinical problems (e.g., nosocomial infections). Quality improvement and risk data, such as medication error reports, can be used to assess practices and determine the need for practice changes. Such sources offer useful information but provide no mechanism to actually guide improvements.

Disciplined Research

Disciplined research is considered the best method of acquiring reliable knowledge that humans have developed. Evidence-based health care compels nurses to base their clinical practice, to the extent possible, on rigorous research-based findings rather than on tradition, authority, or personal experience. However, nursing will always be a rich blend of art and science.

PARADIGMS AND METHODS FOR NURSING RESEARCH

The questions that nurse researchers ask and the methods they use to answer their questions spring from a researcher’s view of how the world “works.” A paradigm is a worldview, a general perspective on the world’s complexities. Disciplined inquiry in nursing has been conducted mainly within two broad paradigms. This section describes the two paradigms and outlines the research methods associated with them.

The Positivist Paradigm

The paradigm that dominated nursing research for decades is called positivism. Positivism is rooted in 19th century thought, guided by such philosophers as Newton and Locke. Positivism is a reflection of a broad cultural movement (modernism) that emphasizes the rational and scientific.

As shown in Table 1.1, a fundamental assumption of positivists is that there is a reality out there that can be studied and known. An assumption is a principle that is believed to be true without verification. Adherents of positivism assume that nature is ordered and regular and that a reality exists independent of human observation. In other words, the world is assumed not to be merely a creation of the human mind. The assumption of determinism refers to the positivists’ belief that phenomena are not haphazard but rather have antecedent causes. If a person has a stroke, a scientist in a positivist tradition assumes that there must be one or more reasons that can be potentially identified. Within the positivist paradigm, research activity is often aimed at understanding the underlying causes of natural phenomena.

| TIP What do we mean by phenomena? In a research context, phenomena are those things in which researchers are interested—such as a health event (e.g., a patient fall), a health outcome (e.g., pain), or a health experience (e.g., living with chronic pain). Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|