CHAPTER 1 Introduction to evidence-based practice

What is evidence-based practice?

There is a famous definition by Professor David Sackett and some of his colleagues which declares evidence-based medicine to be explicit and conscientious attempts to find the best available research evidence to assist health professionals to make the best decisions for their clients.1 Even though this definition was originally given with respect to evidence-based medicine, it is often extended beyond the medical profession and used to define evidence-based practice as well. The definition may sound rather ambiguous, so let us pick its elements apart so that you can fully appreciate what is meant by the term evidence-based practice.

We are familiar with the importance of research for testing theories and for providing us with the background information that forms part of our clinical knowledge. Knowledge about subjects such as anatomy, pathology, psychology and social structures that is essential to our work has been refined over many years through research. Our science-based training gives us models on which to base our clinical management of clients. Of course, having an understanding of the mechanisms is important—for example, we could never have made sense of heart failure or diabetes without understanding the basic mechanisms of these illnesses. Yet, focussing only on the mechanisms of illness can be misleading. Evidence-based practice encourages us to concentrate instead on testing the information directly. This is actually difficult for health professionals to do because we have been trained to consider primarily the underlying mechanisms. Table 1.1 gives some clinical examples to illustrate how the two approaches differ.

TABLE 1.1 Examples of how focussing only on the mechanisms of illness can be misleading

| Previous recommendation (based on a mechanism approach) | Rationale based on a mechanism approach | The empirical research that showed it was wrong |

|---|---|---|

| Put babies onto their fronts when they go to sleep | If they should vomit in their sleep, they might swallow the vomit into their lungs and develop pneumonia (Dr Spock in the 1950s)2 | Observational data have shown that babies are more likely to die of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) if they lie on their fronts, rather than on their backs, when sleeping3 |

| Bed rest after a heart attack (myocardial infarct) | The heart needs resting after an insult in which some of the heart muscle dies | Randomised controlled trials showed that bed rest makes thromboembolism (a dangerous condition in which a clot blocks the flow of blood through a blood vessel) much more likely4 |

| Covering skin wounds after removal of skin cancer | To prevent bacteria gaining access and therefore causing infection | A randomised controlled trial showed that leaving the skin wounds open does not increase the infection rate5 |

That leads us to explore what is meant by the term best evidence from research. Understanding what the different study designs can and cannot help you with and, if you like, what their pros and cons are is important. Part of the skill of evidence-based practice is being able to locate the type of study design that is best suited to the particular type of information that you need in order to make a clinical decision. Further, as we will explain in more detail later in this chapter, some studies have not been designed very well and this reduces the confidence that we have in their conclusions. We therefore need to attempt to find the best quality research that is available.

The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgement that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experiences and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care.1

This definition makes it clear that evidence-based practice also requires clinical expertise, which includes thoughtfulness and compassion as well as knowledge of effectiveness and efficiency. As this is a key aspect of evidence-based practice, we will consider the concept of clinical expertise in more depth in Chapter 15.

A simple definition of evidence-based practice

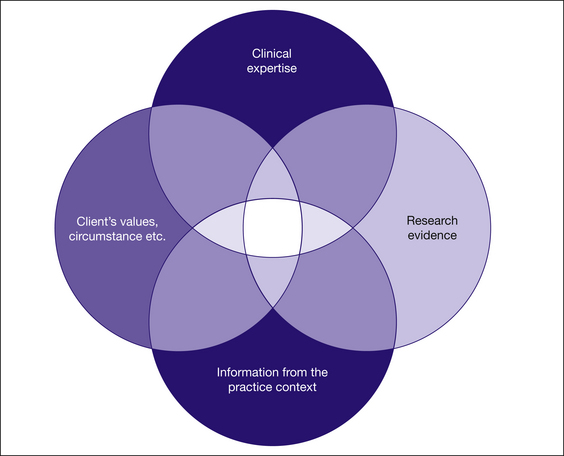

Over time, the definition of evidence-based practice has been expanded upon and refined. Nowadays one of the most frequently used and widely known definitions of evidence-based practice acknowledges that it involves the integration of the best research evidence with clinical expertise and the client’s values and circumstances.6 It also requires the health professional to take into account characteristics of the practice context in which they work. This is illustrated in Figure 1.1. As you read this book, keep this definition in mind. Evidence-based practice is not just about using research evidence as some critics of it may suggest. It is also about valuing and using the education, skills and experience that you have as a health professional. Furthermore, it is also about considering the client’s situation and values when making a decision, as well as considering characteristics of the practice context in which you are interacting with your client. This requires judgement and artistry, as well as science and logic. The process that health professionals use to integrate all of this information is clinical reasoning. When you take these four elements and combine them in a way that enables you to make decisions about the care of a client, then you are engaging in evidence-based practice.

Where did evidence-based practice come from?

It came from a new medical school that started in the 1970s at McMaster University in Canada. The new medical program was unusual in several respects. One difference was that it was very short (only three years). This meant that its teachers realised that the notion of teaching medical students everything that they needed to know was clearly impossible. All they could hope for was to teach them how to find for themselves what they needed to know. How could they do that? The answer was the birth of evidence-based medicine, and hence evidence-based practice.

What happened before evidence-based practice?

This is a good question, and one that clients often ask whenever we explain to them what evidence-based practice is all about. We often relied just on ‘experience’, on the expertise of colleagues who were older and ‘better’ and on what we were taught as students. Each of these sources of information can be flawed and there is good data to show this.7 Experience is very subject to flaws of bias. We overemphasise the mistakes of the recent past, and underestimate the rare mistakes. What we were taught as students is often woefully out of date.8 The health professions are, by their nature, very conservative, and so relying on colleagues who are older and better (so-called ‘eminence-based practice’9) as an information source will often provide us with information that is out of date, biased and, quite simply, often wrong.

This is not to say that clinical experience is not important. In fact, it is so important that it is a key feature in the definition of evidence-based practice. Clinical experience (discussed further in Chapter 15) is knowledge that is generated from practical experience and involves thoughtfulness and compassion as well as knowledge about the practices and activities that are specific to a discipline. However, rather than simply relying on clinical experience alone for decision making, we need to use our clinical experience together with other types of information. To help us make sense of all of the information that we have—from research, from clinical settings, from our clients and from clinical experience—we use clinical reasoning processes.

Is evidence-based practice the same as ‘guidelines’?

No. As you will see in Chapter 13, guidelines are one way that evidence-based practice can help to get the best available evidence into clinical practice, but they are by no means the only way. To make matters worse, guidelines are often not evidence-based. When this is the case, they are worse than any evidence-based practice alternatives.

Is evidence-based practice the same as randomised controlled trials?

No. As you will see in Chapter 4, it is certainly true that randomised controlled trials are the cornerstone of research investigating whether interventions (‘treatments’) work. However, questions about interventions are not the only type of question that health professionals need good research information about. For example, health professionals also need good information about questions of: aetiology (what causes disease or makes it more likely); frequency (how common it is); diagnosis (how we know if the client has the disease or condition of interest); prognosis (what happens to the condition over time); and what the client’s experiences and concerns are in particular situations. In this book, we will primarily focus on how to answer four main types of questions—concerning the effects of interventions, diagnosis, prognosis and clients’ experiences and concerns—as these questions are relevant to a range of health professionals and are asked commonly by them. Each question type requires a different type of research design (of which randomised controlled trials are just one example) to address it. Other research designs include qualitative research, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies and cohort studies. There are many others. They can all be examples of the best evidence for some research questions. This is explored in more depth in Chapter 2.

Can anyone practise evidence-based practice?

Yes. With the right training, practice and experience, any of us can learn how to do evidence-based practice competently. You do not have to be an expert in anything. Having access to the internet and databases (such as PubMed and the Cochrane Library) is good. And having some trustworthy colleagues to check your more surprising findings is also good.

Why is evidence-based practice important?

Evidence-based practice also has an important role to play in ensuring that health resources are used wisely and that relevant evidence is considered when decisions are made about funding health services. There are finite resources available to provide health care to people. As such, we need to be responsible in our use of healthcare resources. For example, if there is good quality evidence that a particular intervention is harmful or not effective and will not produce clinically meaningful improvement in our clients, we should not waste precious resources providing this intervention—even if it is an intervention that has been provided for years. That is not to say, however, that if no research exists that clearly supports what we do, the interventions that we provide should not be funded. As discussed later in this book, absence of evidence and evidence of ineffectiveness (or evidence of harm) are quite different things.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree