CHAPTER 16 Implementing evidence into practice

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

Implementation is a complex but active process which involves individuals, teams, systems and organisations. Translating evidence into practice requires careful forward planning.1 While some planning usually does occur, the process is often intuitive.2 There may be little consideration of potential problems and barriers. As a consequence, the results may be disappointing. To help increase the likelihood of success when implementing evidence, this chapter provides a checklist for individuals and teams to use when planning the implementation of evidence.

Implementation terminology

A number of confusing terms appear in the implementation literature. Different terms may mean the same thing in different countries. To help you navigate this new terminology, definitions relevant to this chapter are provided in Box 16.1.

BOX 16.1 DEFINITIONS OF IMPLEMENTATION TERMINOLOGY

Implementation case studies

To help you understand the process of implementation, we will now consider three case studies. The first case study involves reducing referrals for a test procedure (X-rays) by general practitioners for people who present with acute low back pain.7 This case example involves the overuse of X-rays. The other two case studies involve increasing the uptake of two underused interventions: cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescents with depression8 and community travel and mobility training for people with stroke.9,10

Case study 1: Reducing the use of X-rays by general practitioners for people with acute low back pain

Low back pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal conditions seen by general practitioners,11 but also by allied health practitioners such as physiotherapists, chiropractors and osteopaths. Clinical guidelines recommend that people presenting with an episode of acute non-specific low back pain should not be sent for an X-ray because of the limited diagnostic value of this test for this condition.12 In Australia, about 28% of people who visit their local general practitioner with acute low back pain are X-rayed,13 with even higher estimates in the USA and Europe.7 Put simply, X-rays are over-prescribed and costly. Instead of recommending an X-ray, rest and passive treatments, general practitioners should advise people with acute low back pain to remain active.12

In this instance, the evidence–practice gap is the overuse of a costly diagnostic test which can delay recovery. Recommendations about the management of acute low back pain, including the use of X-rays, have been made through national clinical guidelines.12 A program to change practice, in line with guideline recommendations, is the focus of one implementation study in Australia7 and will be discussed further throughout this chapter.

Case study 2: Increasing the delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy to adolescents with depression by community mental health professionals

Cognitive behavioural therapy has been identified as an effective intervention for adolescents with depression, a condition that is on the increase in developed countries.14 Outcomes from cognitive behavioural therapy that is provided in the community are superior to usual care for this population.15 Clinical guidelines recommend that young people who are affected by depression should receive a series of cognitive behavioural therapy sessions. However, a survey of one group of health professionals in North America found that two-thirds had no formal training in cognitive behavioural therapy and no prior experience using a treatment manual for cognitive behavioural therapy.8 In other words, they were unlikely to deliver cognitive behavioural therapy if they did not know much about it. Furthermore, almost half of the participants in that study reported that they never or rarely used evidence-based treatments for youths with depression, and a quarter of the group had no plans to use evidence-based treatment in the following six months. Subsequently, that group of mental health professionals was targeted with an implementation program to increase the uptake of the underused cognitive behavioural therapy. The randomised controlled trial that describes this implementation program8 and the evidence–practice gap (underuse of cognitive behavioural therapy) will also be discussed throughout this chapter.

Case study 3: Increasing the delivery of travel and mobility training by community rehabilitation therapists to people who have had a stroke

People who have had a stroke typically have difficulty accessing their local community. Many experience social isolation. Up to two-thirds of people who have had a stroke do not return to driving16,17 and up to 50% experience a fall at home in the first six months.18 Australian clinical guidelines recommend that community-dwelling people with stroke should receive a series of escorted visits and transport information from a rehabilitation therapist, to help increase outdoor journeys.19 Although that recommendation is based on a single randomised controlled trial,20 the size of the treatment effect was large. The intervention doubled the proportion of people with stroke who reported getting out as often as they wanted and doubled the number of monthly outdoor journeys, compared to participants in the control group.20

In order to see whether people with stroke were receiving this intervention from community-based rehabilitation teams in a region of Sydney, local therapists and the author of this chapter (AMC) conducted a retrospective medical record audit. The audit revealed that therapists were documenting very little about outdoor journeys and transport after stroke. Documented information about the number of weekly outings was present in only 14% of medical records (see Table 16.1). Furthermore, only 17% of people with stroke were receiving six or more sessions of intervention that targeted outdoor journeys, which was the ‘dose’ of intervention provided in the original trial by Logan and colleagues.20,21 The audit data highlighted an evidence–practice gap, specifically, the underuse of an evidence-based intervention. This example will be used as the third case study throughout the chapter, to illustrate the process of implementation.

TABLE 16.1 Summary of baseline file audits (n=77) involving five community rehabilitation teams describing screening and provision of an evidence-based intervention∗ for people with stroke

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Screening for outdoor mobility and travel | ||

| Driving status documented (pre-stroke or current) | 37 | 48 |

| Preferred mode of travel documents | 27 | 35 |

| Reasons for limited outdoor journeys documented | 26 | 34 |

| Number of weekly outdoor journeys documented | 11 | 14 |

| Outdoor journey intervention | ||

| At least 1 session provided | 44 | 57 |

| 2 sessions or more provided | 27 | 35 |

| 6 sessions or more provided | 13 | 17 |

∗ Intervention to help increase outdoor journeys as described by Logan and colleagues.20, 21

The process of implementation

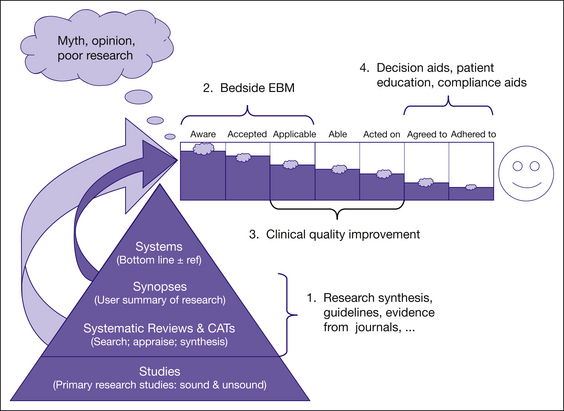

Model 1: The evidence-to-practice pipeline

The ‘evidence pipeline’ described by Glazsiou and Haynes22 and shown in Figure 16.1 provides a helpful illustration of steps in the implementation process. This metaphoric pipeline highlights how leakage can occur, drip by drip, along the way from awareness of evidence to the point of delivery to clients. First, there is an ever-expanding pool of published research to read, both original and synthesised research. This large volume of information causes busy professionals to miss important, valid evidence (awareness). Then, assuming they have heard of the benefits of a successful intervention (or the overuse of a test procedure), professionals may need persuasion to change their practice (acceptance). They may be more inclined to provide a familiar intervention with which they are confident and which clients expect and value. Hidden social pressure from clients and other team members can make practice changes less likely to occur. Busy professionals also need to recognise appropriate clients who should receive the intervention (or not receive a test procedure). Professionals then need to apply this knowledge in the course of a working day (applicability).

FIGURE 16.1 The research-to-practice pipeline

Reproduced from: Glasziou P and Haynes B, The paths from research to improved health outcomes, 10, 4–7, 2005, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd22

Some test procedures and interventions will require new skills and knowledge. For example, the delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy to adolescents with depression involves special training, instruction manuals, extra study and supervision. A lack of skills and knowledge may be a barrier to practice change for professionals who need to deliver the intervention (able). A further challenge is that, while we may be aware of an intervention, accept the need to provide it and are able to deliver it, we may not act on the evidence all of the time (acted on). We may forget—or more likely—we may find it difficult to change well-established habits. For example, general practitioners who have been referring people with acute back pain for an X-ray for many years may find this practice difficult to stop.

Model 2: Plan and prepare model

A different process of implementation has been proposed by Grol and Wensing.3 Their bottom line is ‘plan and prepare’. While intended for the implementation of clinical guidelines, the principles apply equally well to the implementation of test ordering, outcome measurement or interventions and for procedures that are either under- or overused. The ‘plan and prepare’ model involves five key steps:

Using the travel and mobility training study as an example, the two primary aims were:

Examples of ‘targets’ or indicators of implementation success were also documented early in this project, for both groups.9 The first target was that rehabilitation therapists would deliver an outdoor mobility and travel training intervention20,21 to 75% of people with stroke who were referred to the service (that is, a change in professional behaviour). The second target was that 75% of people with stroke who received the intervention would report getting out of the house as often as they wanted and take more outdoor journeys per month compared to pre-intervention.

Demonstrating an evidence–practice gap (gap analysis)

Surveys for gap analysis

A survey can be developed and used, with health professionals or clients, to explore attitudes, knowledge and current practices. If a large proportion of health professionals admit to knowing little about, or rarely using, an evidence-based intervention, this information represents the evidence–practice gap. In the cognitive behavioural therapy example discussed earlier,8 a local survey was used to explore attitudes to, knowledge and use of cognitive behavioural therapy by community mental health professionals.

The process of developing a survey to explore attitudes and behavioural intentions has been well documented in a manual by Jill Francis and colleagues.23 The manual is intended for use by health service researchers who want to predict and understand behaviour and measures constructs associated with the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Behavioural theories will be discussed in a later section of this chapter. If you intend to develop your own local survey or questionnaire, whether the survey is for gap analysis or barrier analysis, it is recommended that you consult this excellent resource. Sample questions include: ‘Do you intend to do (intervention X) with all of your clients?’ and ‘Do you believe that you will be able to do X with your clients?’

Audits for gap analysis

Audit is another method which can be used to demonstrate an evidence–practice gap. A small medical record audit can be conducted using local data (for example, 10 medical records may be selected, reflecting consecutive admissions over three months). The audit can be used to determine how many people with a health condition received a test or an evidence-based intervention. For example, we could determine the proportion of people with acute back pain for whom an X-ray had been ordered in a general practice over the previous three months. We could also count how frequently (or rarely) an intervention was used.

In the travel and mobility training study, it was possible to determine the proportion of people with stroke who had received one or more sessions from an occupational therapist or physiotherapist to help increase outdoor journeys.9 Baseline medical record audits of 77 consecutive referrals across five services in the previous year revealed that 44/77 (57%) people with stroke had received at least one session targeting outdoor journeys, but 22/77 (35%) had received two or more sessions, and only 13/77 (17%) had received six or more sessions. In the original randomised controlled trial that evaluated this intervention,20, 21 a median of six sessions targeting outdoor journeys had been provided by therapists. This number of sessions was considered the optimal ‘dose’ (or target) of intervention.

It has been recommended that more than one method should be used to collect data on current practice, as part of a gap analysis (for example, an audit and a survey).2 Collecting information from a small but representative sample of health professionals or clients, using both qualitative and quantitative methods, can be useful.2

In Australia, examples of evidence–practice gaps in health care are summarised annually by the National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS).24 This organisation highlights gaps between what is known and what is practised. For example, recent reports have described evidence–practice gaps in the following areas: underuse of smoking cessation programs by pregnant mothers, suboptimal management of acute pain and cancer pain in hospitalised patients and underuse of preventative interventions for venous thromboembolism in hospitalised patients.25

Identifying barriers and enablers to implementation (barrier analysis)

Methods for identifying barriers are similar to those used for identifying evidence–practice gaps: surveys, individual and group interviews (or informal chats) and observation of practice.26,27 Sometimes it may be helpful to use two or more methods. The choice of method will be guided by time and resources, as well as local circumstances and the number of health professionals involved.

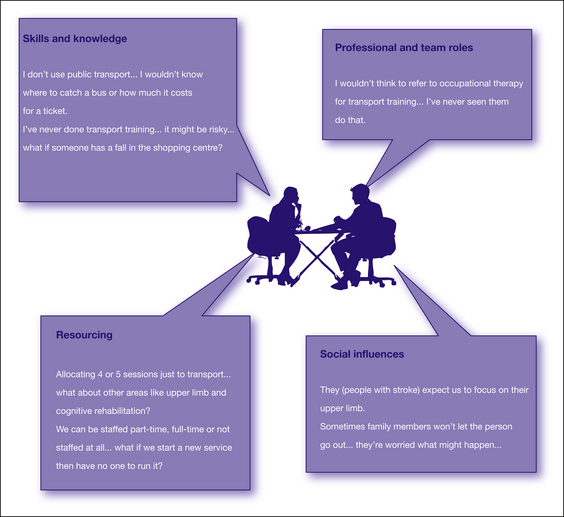

The travel and mobility training study involved community occupational therapists, physiotherapists and therapy assistants from two different teams. Individual interviews were conducted with these health professionals. Interviews were tape-recorded with their consent (ethics approval was obtained), and the content was transcribed and analysed. The decision to conduct individual interviews was based on a desire to find out what different disciplines knew and thought about the planned intervention and about professional roles and responsibilities. Rich and informative data were obtained;10 however, this method produced a large quantity of information which was time-consuming to collect, transcribe and analyse. A survey or focus group would be more efficient for busy health professionals to use in practice. Examples of quotes from the interviews and four types of barriers from this study are presented in Figure 16.2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree