Introduction

The midwife is the expert in normal childbirth. It is her role to promote and support the normal physiology of labour, whilst noting any signs of variations from the norm that might harm the woman or her baby. The Midwives’ Rules and Standards (NMC 2012) require the midwife to report any deviations from the norm to another suitably qualified health professional (who may be a doctor) with the necessary skills required to manage the situation. In order to do this, the midwife should have a clear understanding of what is meant by a ‘normal’ labour and birth. The focus of this chapter will be on the midwife’s role in the promotion of a normal labour resulting in a safe and memorable childbirth experience for the woman and her family.

- Birth without caesarean section

- Birth without assisted delivery (ventouse or forceps)

- No induction of labour

- No regional anaesthesia (epidural or spinal block)

Definitions of normality

There is currently no standard or universally acceptable definition of a ‘normal’ birth. The term has different meanings for obstetricians, midwives and members of the public. Even within the midwifery profession, individuals may hold different definitions, ranging from anything short of a caesarean section at one end of the scale to a totally physiological birth without any intervention at the other. Most people, however, would probably consider normal birth to be somewhere between these two extremes (Mead 2004).

For the purpose of statistics, the government has adopted the definition of normal birth proposed by the Maternity Care Working Party (2007) (see Box 7.1)

The World Health Organization (WHO 1996) advises that interventions to the physiological process of birth should not occur without a clear rationale. Examples of such interventions are induced labour, restriction of a woman’s mobility, the use of continuous fetal monitoring, the withholding of food and fluid and the routine use of vaginal examinations to assess labour progress.

Stages of labour

Labour has been traditionally divided into three stages:

The organisation of labour into these three stages has been challenged by some writers, who suggest that labour should be considered as a continuum, with physiological, physical and emotional factors playing an integral part in the process (Walsh 2011).

Promoting spontaneous labour: avoiding induction of labour

Over 20% of pregnant women have their labour induced (BirthChoiceUK 2012). In most cases, this is because the pregnancy is prolonged but is otherwise normal. It is current practice in most maternity units to offer routine induction of labour to women whose pregnancy goes beyond 41 weeks (NICE 2008). Whilst there is little argument against induction for serious obstetric complications, it should be remembered that the process is an invasive procedure requiring many interventions.

‘Sweeping the membranes’

This process involves the midwife inserting a gloved forefinger through the cervical os and rotating it in a circular fashion to separate the membranes from the lower uterine area. This causes prostaglandins to be released which promote cervical effacement (thinning and stretching) and dilation. Research shows that ‘a sweep’ increases the chances of labour starting spontaneously within the next 48 hours and can reduce the need for other methods of induction (NICE 2008). It is only possible if the cervix is already open sufficiently to admit a finger. This should never be forced. This process may be carried out in the antenatal clinic or the woman’s home and may result in a ‘show’ (a lightly blood-stained mucous discharge) and some mild cramps afterwards. The current NICE guidelines recommend that a sweep should be offered prior to any induction process (NICE 2008).

Onset of spontaneous labour

The timing of the start of labour in humans is less precise than it is in other species. It is suggested that the average day of onset is 39.6 weeks’ gestation (Howie & Rankin 2011a). The underlying mechanism of labour is still not fully understood although the timing of its onset is believed to be related to fetal brain activity. It is suggested that adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) is released from the fetal pituitary gland which causes the woman’s hormone progesterone to be converted to oestrogen. This in turn increases the sensitivity of the uterus to prostaglandins and oxytocin, which are produced by both the mother and the fetus (Howie & Rankin 2011a). These hormones cause the uterine muscle fibres to contract and shorten, so stimulating the beginning of labour. Studies demonstrate that where there is an abnormality in the fetal hypothalamus and pituitary gland, prolonged pregnancy may follow (Johnson & Everitt 2007).

She spent the rest of the day in bed and slept deeply. At midnight, contractions resumed and became longer, stronger and more frequent. She went into hospital at 0200 hours and eventually gave birth at 1100 hours. This was almost 3 days after she had first noticed the show and to Fiona seemed like a very long time.

Signs that labour is starting

Onset of uterine contractions

As labour begins, the formerly painless uterine tightenings (Braxton Hicks contractions) increase in frequency and the woman starts to feel discomfort with the contractions. This may be felt as pain in the lower abdomen, the lower back or the tops of the legs. The woman will eventually notice that this discomfort coincides with a tightening of her uterus. At first, the uterine contractions occur approximately every 15–20 min and may only last 20–30 seconds. However, as labour progresses they begin to increase in length, strength and frequency, leading to effacement and dilation of the cervix.

Passage of a Mucous ‘show’

During pregnancy, the cervical canal contains a plug of mucus (the operculum), which is believed to protect the fetus from infection. As the cervix begins to dilate in early labour, this Mucous plug will often be dislodged and the woman will notice a blood-stained discharge in her underwear or after she has passed urine. This is often the first sign that labour is imminent, although it may still be some hours or days before it begins in earnest. Some women are never aware of the passage of this show.

Spontaneous rupture of the membranes (‘the waters breaking’)

This may occur before the onset of labour or at any time during labour. It is not a true sign that labour has begun unless it is accompanied by dilation of the cervix.

Spontaneous rupture of the membranes can be recognised by the sudden loss of a significant amount of clear fluid from the vagina. However, for some women this may not be instantly recognisable if only very small amounts of fluid are lost. If the fetal presenting part is engaged deeply in the pelvis then this could well be the case. Small amounts of fluid loss could be mistaken for urinary incontinence, which is common in the latter stages of pregnancy due to excessive pressure of the fetus on the bladder. The midwife will need to take a careful history from the woman. Continued observation of fluid lost from the vagina will usually lead to a definite confirmation that spontaneous rupture of the membranes has occurred. Approximately 60% of women will start to labour spontaneously within 24 hours of their membranes rupturing (NICE 2007).

Other signs

Some women feel nauseous as labour approaches and others experience mild diarrhoea as uterine activity stimulates bowel movement. Some women become preoccupied with cleaning and tidying their homes in preparation for the arrival of the newborn. This is referred to as the ‘nesting’ instinct (Johnston 2004, Odent 2003).

Midwifery care in early labour

When the midwife receives a call from a woman in early labour, she needs to take a history to ascertain whether the woman should come directly into hospital for assessment or whether she can stay at home and await further events. If the woman has no complications and is in early labour with contractions occurring irregularly and infrequently (maybe every 15–20 min) then it is better if she remains at home. This is known as the latent phase of labour. A significant link between later admission to hospital and a positive birth outcome (for example, a reduced caesarean section rate) has been shown (Ghacero & Enabudosco 2006).

Increased levels of stress which a woman may experience on admission to the unfamiliar environment of the modern labour ward may lead to an increased production of catecholamines. These are the ‘fight or flight’ hormones (adrenaline and noradrenaline) and they tend to inhibit the production of oxytocin (Peled 1992, Wuitchik et al. 1989). As oxytocin causes contraction of the uterine muscle, it follows that a reduction in oxytocin leads to diminished contractions and a slowing down of the labour process. It is suggested that ensuring that hospital labour wards are kept as calm, peaceful and private as possible will lead to better birth experiences and outcomes (Hodnett et al. 2010).

The midwife could suggest to the woman that she has a warm bath to help her relax, that she tries to get as much rest as possible and that she has a light meal and drinks plenty of fluid in order to prepare herself for the onset of the active phase of labour. Sometimes, however, despite being in early labour, a woman may decide that she wants to go into hospital for reassurance from a midwife that all is progressing normally.

If the woman reports any complications such as vaginal bleeding which appears to be more than a ‘show’, or if she has any medical disorders such as diabetes, cardiac problems, pregnancy-induced hypertension or a known malpresentation such as breech, she should be asked to come directly to the labour ward. This is in accordance with the Midwives’ Rules and Standards (NMC 2012), which state that where a deviation from the norm becomes apparent, a practising midwife should inform an appropriately qualified healthcare professional.

Women are also usually asked to come into hospital if they think that their membranes have broken. This is so that the midwife can exclude any signs of infection, such as a raised temperature and pulse rate, as infection poses a risk to the fetus when the protective membranes have ruptured. Women with ruptured membranes: and without signs of infection or fetal compromise are often discharged home to await the onset of labour, once they have been assessed. In 60% of cases, labour will start spontaneously within 24 hours (NICE 2008). If it does not occur spontaneously, then induction of labour may need to be considered (NICE 2008).

Initial examination

On arrival at the labour ward, the woman and her birth partner should be welcomed by the midwife who will be caring for them. In most labour wards today, the woman will not know her midwife and this initial meeting is of great importance.

Pregnancy history

Before examining the woman, the midwife should review her medical records. Most women will bring them to the labour ward on their admission. The progress of the current pregnancy should be ascertained as well as the outcome of any previous pregnancies, as this may have a bearing on the current one. The woman’s general health and any medical history of note should also be considered.

Physical examination

The midwife should observe the general condition of the woman. This includes an assessment of how she is coping with the contractions and whether she appears anxious or fearful.

The general colour of the woman should be noted. Extreme pallor, flushed skin or cyanosis could be an indication that there are underlying medical problems, such as anaemia, heart disease or infection, which might affect the management of care. Signs of oedema should also be noted. It is very common for women in the latter stages of pregnancy to have swollen fingers and feet. However, if the oedema is marked, and particularly if it involves the face (the woman’s birthing partner could be asked for his or her opinion in relation to this), this may be a sign of pre-eclampsia (also referred to as pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH)) which could have serious implications for the woman and her baby.

Physical examination includes taking the woman’s pulse, blood pressure and temperature. These recordings should be noted in the woman’s records as they will act as baseline readings as the labour progresses.

A sample of the woman’s urine should be tested on admission and then regularly throughout the labour. If protein is detected, then this may indicate the presence of PIH, although it may also be due to contamination with amniotic fluid if the membranes have broken.

The presence of ketones (ketonuria) suggests that the woman has not eaten for some time or has suffered from excessive vomiting. Ketonuria is an indication that the body is using fat as a major source of energy rather than carbohydrate.

A small amount of ketonuria is to be expected during labour as a physiological response to the increased energy demands within the body at this time. However, if large amounts of ketones are present, this may indicate a severe depletion of the body’s energy source which could lead to a reduction in uterine activity and slowing down of the progress of labour.

An abnormality in any of these readings should be reported to the obstetrician as they may indicate an underlying problem with the general health of the woman or with the progress of her labour.

Assessment of the progress of labour

There are many ways of assessing a woman’s progress in labour, requiring midwives to draw on their knowledge, skills and experience.

Observation of the woman’s behaviour

A woman in the latent first stage of labour may not display any outward signs. As cervical dilation advances and the woman enters the active phase of labour, she may become restless and uncomfortable and suffer pain. She will probably want to change position frequently, often finding a mobile, upright or forward-leaning posture more comfortable. It is thought that this instinctive behaviour assists the descent and rotation of the fetus.

Vocal changes are often noted as labour progresses. In early labour, conversation and interaction are usually unhindered, but as the frequency and intensity of contractions increase, women find it increasingly difficult to hold a conversation and will often close their eyes in concentration until the pain passes. The level of breathing changes as contractions intensify: as the second stage approaches, women are often heard to make a deep, slow ‘mooing’ sound which is associated with the urge to bear down. This may increase in intensity as the fetus is expelled. Women should not be discouraged from vocalising in labour and indeed, it may be unhelpful to attempt to do so (McKay & Roberts 1990, RCM 2012c).

The urge to bear down, or push, is usually automatic and beyond the woman’s conscious control. As the second stage intensifies, the urge will become overwhelming and women may briefly hold their breath and bear down, often several times, during the peak of each contraction. However, when the baby is in an occipito-posterior position, this may cause an urge to push well before full cervical dilation. If in doubt, a vaginal examination may be undertaken with the woman’s consent to confirm full dilation of the cervix.

Outward signs

Natal line

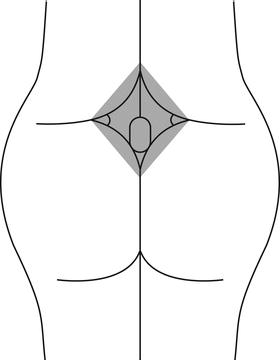

One non-invasive means of estimating progress is to observe the ‘purple line’ that slowly ascends from the anal margin to the top of the natal cleft (skin between the buttocks). It is generally supposed that this line moves at roughly the same rate as the cervix dilates, reaching the top of the natal cleft at full dilation.

A recent study (Shepherd et al. 2010) found that the purple line does exist and that there is a medium positive correlation between the length of the line and both cervical dilation and the station of the fetal head. Where the line is visible, it may provide a useful guide for how labour is progressing. However, further research is needed to assess whether measurement of the purple line is acceptable to both labouring women and midwives.

The rhombus of Michaelis

The rhombus of Michaelis is a kite-shaped area over the lower back that includes the lower lumbar vertebrae and sacrum (Figure 7.1). It is believed that this area of bone moves backwards during the second stage of labour, pushing out the wings of the ilea and increasing the pelvic diameter (Wickham & Sutton 2005). This allows more space for the fetus to descend through the pelvis. Sutton notes that when in a forward-leaning posture, a lump appears on the woman’s back, at and below waist level. This happens at the start of the second stage. This is thought to be the reason why, if a woman is labouring in a semi-supine position, she may automatically reach up to find something to hold on to and arch her back (Wickham & Sutton 2005).

Anal dilation

As the presenting part reaches the pelvic floor and begins to displace the muscle and tissue, anal dilation may be noted. This is usually a sign that the second stage of labour is reaching its culmination. The woman may pass an involuntary bowel motion at this time if her rectum is full, as the pressure of the presenting part flattens the rectum against the sacral bone, expelling any contents.

However, anal dilation may be caused by deep engagement of the presenting part or early pushing (Howie & Rankin 2011d), so should not be taken as a definitive indicator of progress if no other signs are seen.

Vulval gaping/appearance of the presenting part

As the second stage progresses, the vaginal opening stretches and the perineal body flattens and distends. The presenting part may be visible on parting the labia. This is usually a sure sign of progress when noted for the first time. However, if there is a lot of caput and moulding (swelling and distortion of the fetal skull) this may be misleading, as the bony part of the fetal skull may be much higher in the birth canal than it appears. Caput and moulding may cause the scalp to protrude through the cervix prior to full dilation, as may a breech (Howie & Rankin 2011d).

Spontaneous rupture of membranes

The most common time for the woman’s membranes to break naturally is at the end of the first stage of labour when the cervix is fully dilated and thus unable to support the forewaters against the force of uterine contractions (Howie & Rankin 2011b).

Observation of woman’s psychological state

The transitional phase

The definition of the transitional phase varies but it is commonly used to describe the period from the end of the first stage of labour to full dilation of the cervix (Downe 2011) It is essentially a midwifery observation and relies on the midwife knowing the woman and recognising changes in her behaviour that indicate that birth is imminent.

During the transitional phase, a woman’s behaviour and mental state may change and this phase often represents a psychological low point when the woman becomes overwhelmed by both physical and emotional pain (Downe 2011). She may become very agitated and restless, display aggression, irritability and irrational behaviour, such as wanting to go home or demanding a caesarean section. It is important to remember that this phase is temporary and not a reflection of her true personality.

Another manifestation of the transitional phase is an apparent withdrawal of the woman into herself. She may close her eyes, cease talking and appear unaware of what is happening around her. Leap (2000) explains that the woman is subconsciously focusing her energy and concentration in preparation for the supreme effort of giving birth.

Abdominal palpation and auscultation

The purpose of abdominal palpation during labour is to assess the lie, presentation, position, flexion and descent of the presenting part (usually the head). These findings are significant when done repeatedly over a period of time, as an indicator of how far labour has progressed, and give some indication of how it is likely to continue. Continuity of midwife is preferable as findings may be subjective.

The most common findings of abdominal palpation are a fetus that is in a longitudinal lie, a cephalic (head-down) presentation and a left occipito-anterior (LOA) position. The head is normally flexed and descent is measured in fifths palpable above the symphysis pubis. When 2/5th or less is palpable, the head is said to be engaged. Engagement is defined as the widest part having passed through the pelvic brim (Howie & Rankin 2011b). In primiparous women, the head is normally engaged before labour commences. In multiparous women, the head may still be free at the start of labour. As labour progresses, the fetus will gradually move into a direct occipito-anterior (OA) position and the head will descend further until no fifths are palpable through the abdomen.

Listening to the fetal heart allows the midwife to assess fetal well-being and also enables descent of the fetus to be tracked. The point at which the heart sounds are loudest will gradually change as the fetus rotates and descends. Once deeply engaged, it may be difficult to auscultate the heart sounds with a Pinard stethoscope, due to the positioning of the fetal chest behind the symphysis pubis.

Monitoring of contractions

Contractions generally begin as mild, period-type cramps that are often irregular and intermittent continuing for hours or even days (Walsh 2011). This happens as the cervix is effacing and beginning to dilate. This early period is often referred to as the latent phase and varies in length: many women will not be aware when it began. Indeed, some women may believe that they are in established labour. The midwife will need to give careful explanations to help the woman understand what is actually happening to her body.

Eventually, the latent phase of labour merges into the active phase, and contractions start to become regular and closer together. The active phase of labour is defined as progressive cervical dilation with regular, painful contractions (NICE 2007). In the earlier part of the active phase, contractions may be as little as 2:10 (i.e. twice in 10 minutes), lasting 30 seconds. They gradually increase in length, strength and frequency as labour progresses, up to a maximum of around 5:10 (five times in 10 min), lasting over a minute with little break in between.

The midwife can place her hand on the woman’s abdomen at fundal level in order to assess the length and frequency of contractions. It is difficult to assess the strength of a contraction through palpation – the woman herself is a better judge of that.

Some women experience a temporary lull in contractions at the end of the first stage of labour, but prior to the onset of expulsive contractions. This coincides with the presenting part descending and rotating as it reaches the pelvic floor (Howie & Rankin 2011d). This period is sometimes referred to as the latent phase of second stage, before contractions begin to feel expulsive, and it should not be assumed that labour has slowed down or ceased.

Vaginal examination

Some hospitals will have a policy of performing regular vaginal examinations (VE) throughout labour, regardless of the risk status of the woman. Midwives covering homebirths or working in birth centres may take a more relaxed approach, as their clients will by definition be low risk and thus they may only undertake a VE when there is a clear clinical need. In consultant units, however, midwives are increasingly working in an environment in which the evidence from VE supersedes all other indications of progress. There is thus a risk that midwives and students will lose confidence in other means of assessing progress (Sookhoo & Biott 2002).

The first VE is often carried out soon after admission to the delivery suite. However, depending on local policy, the midwife may wait until she is sure that the woman is in active labour. It is common practice to carry out a VE to confirm onset of the second stage of labour, though this may not be necessary if the presenting part is already visible. However, if the woman displays an urge to push when there is doubt about progress in labour, a vaginal examination may be carried out.

Vaginal examination allows the progress of labour to be assessed through a number of indicators.

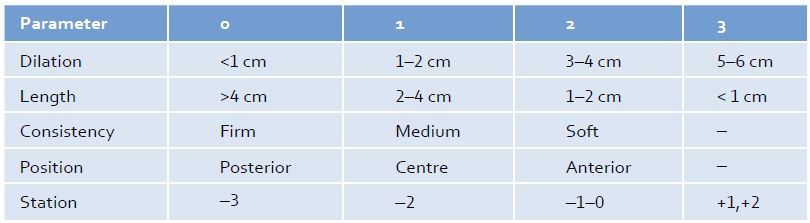

The state of the cervix

The midwife will assess the position, effacement, consistency and dilation. In early labour, these findings may be expressed using the Bishop’s score system, a tabular representation which allocates points to each factor (see Table 7.1). The higher the number of points, the more advanced the state of cervix towards established labour.

Table 7.1 Bishop’s score

Adapted from: www.preg.info/BirthNotes/pdf/birth_notes_bookmarked.pdf (accessed May 2013).

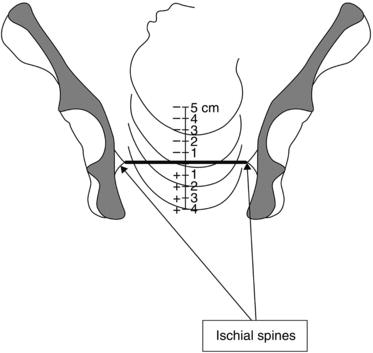

The station of the presenting part

Even if the cervix is closed, the midwife will be able to ascertain the descent of the presenting part (PP) through the pelvis. This should have been estimated by abdominal palpation prior to commencing the VE. The PP is measured in relation to the ischial spines (Figure 7.2) and is estimated in centimetres. The ischial spines may be felt as blunt, bony prominences on stretching the examining fingers to the sides of the vaginal wall. Thus a position of 0 means that the PP is level with the ischial spines: minus 1 means 1 cm above the ischial spines; plus 1 means 1 cm below (see Figure 7.2). The midwife would expect the PP to descend steadily throughout labour as the cervix dilates. However, midwives may have difficulty locating the ischial spines in some women if they are not particularly prominent and the use of this landmark is highly subjective and therefore may not always be a very accurate tool for measuring descent of the fetus.

Position of the cervix

Prior to the onset of labour, the cervix points towards the posterior vaginal wall. On VE, it may be very difficult to locate. From the end of pregnancy until the onset of established labour, it gradually becomes central and eventually anterior facing. Thus the ease with which the cervix can be reached is an indicator of progress in the latent or early phase of labour.

The size and shape of the bony pelvis

The midwife conducting the VE will note any unusual findings such as a narrow pubic arch or a prominent sacrum, either of which might impede the progress of labour. A higher than expected PP coupled with an unusual pelvic structure is a likely indicator that labour will not progress to vaginal delivery, regardless of the strength of contractions. This must be reported urgently to the senior obstetrician as a caesarean section is likely to be needed.

The position of the presenting part

If the cervix is sufficiently dilated, it will be possible for the midwife to assess the attitude (flexed or deflexed) of the fetal head by feeling for the fontanelles. A deflexed head at the start of labour would be expected to gradually flex, so that the posterior fontanelle becomes readily palpable. Lack of flexion may be an indicator of poor progress due to an unfavourable fetal position or to inefficient contractions.

The position of the fetus can be determined through palpation of the sutures on the fetal skull. By noting the position and direction of the sutures, the midwife can assess whether the fetus has rotated into a good position for birth. If VEs are repeated over a period of time, the midwife should be able to track the progress of the fetus as it rotates and descends through the birth canal. These are important signs of progress in labour and a lack of rotation, flexion and descent may indicate an obstruction to normal labour.

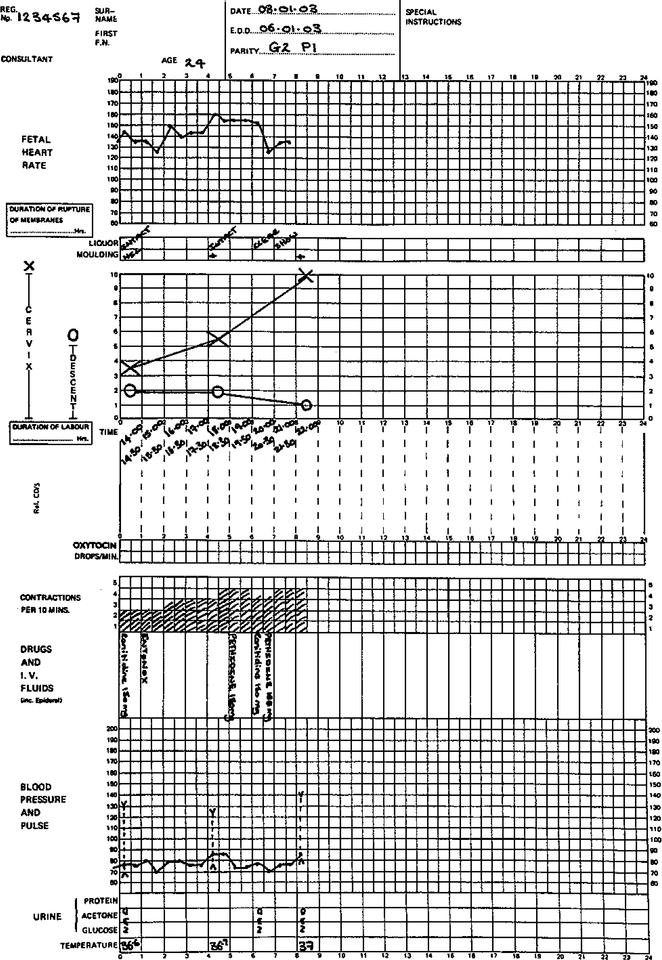

The partogram

The standard tool in hospitals for assessing the progress of labour is the partogram (sometimes known as the partograph). This maps cervical dilation and descent of the PP along a time-scale, with space to include basic observations such as the fetal heart, length, strength and frequency of contractions, maternal temperature, pulse, urine output and blood pressure (NICE 2008). It is commonly used once a woman is in ‘established’ labour – local policies may differ in their definition of this term but it usually refers to a state of regular contractions becoming longer, stronger and closer together with progressive dilation of the cervix and descent of the PP.

The partogram requires the midwife to undertake physical observations and document the findings at regular intervals throughout labour. The woman’s progress is thus represented in the form of a graph, allowing her carers to see at a glance how she has progressed, which may give an indication of the normality of her labour. However, the value of the partogram depends on an accurate diagnosis of the onset of labour and this is often unknown.

The purpose of a partogram is to detect dysfunctional physical patterns in labour, thereby allowing early intervention before the mother or fetus becomes compromised. Over time, there have been modifications to the use of this assessment tool, including the introduction of an alert and an action line with the action line being 2 hours to the right of the alert line and meaning that augmentation of the labour is recommended (Church & Hodgson 2011).

Despite its widespread use, the partogram is controversial as it depends on clock-watching and demands regular physical interventions (Figure 7.3). It takes little account of the subtler signs of progress.

Figure 7.3 A partogram. Reproduced with permission from Symonds M, Symonds IM (2003) Essential Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 4th edn. London: Churchill Livingstone.