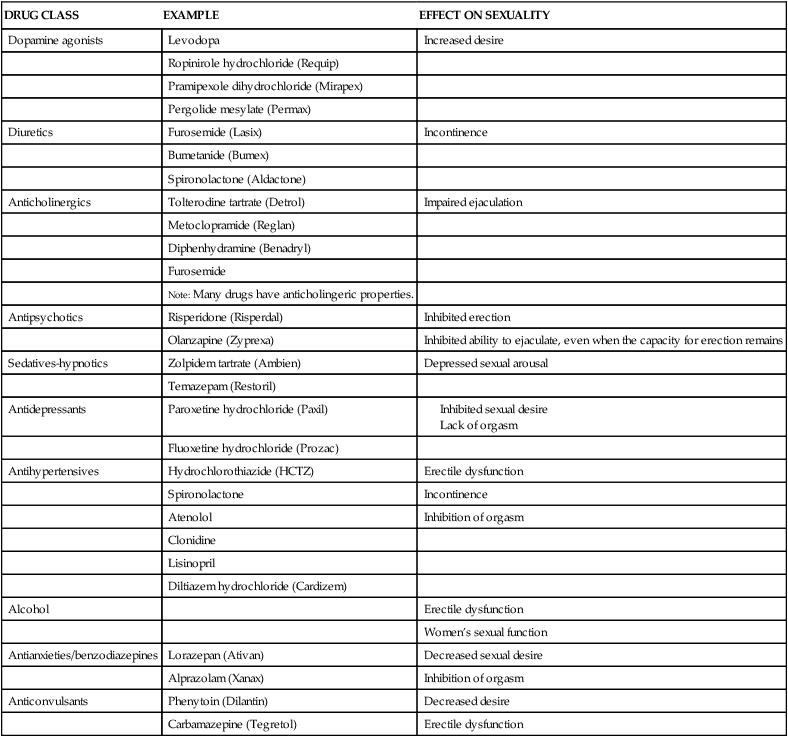

Phyllis J. Atkinson, RN, MS, GNP-BC, WCC On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify the myths surrounding sexual practice in older adults. 2. Explore the possible reasons for a nurse’s hesitancy in assisting older adults with fulfilling their sexual desires. 3. Describe the normal changes of the aging male and female sexual systems. 4. Describe the pathologic problems of the aging male and female sexual systems. 5. Explain the influence of dementia on older adults’ sexual desires and practices. 6. Discuss the environmental barriers to older adults’ sexual practices and the ways to manipulate these barriers. 7. Conduct an assessment interview related to an older adult’s sexuality and intimacy. 8. State two nursing diagnoses applicable to older adults’ sexual practices. 9. Plan nursing interventions for assisting older adults in fulfilling their sexual desires. 10. State one alternative to an older adult’s sexual practice other than sexual intercourse. Sexuality is an important part of health, general well-being, and quality of life. Human sexuality includes various types of intimate activity, as well as the sexual knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and values of individuals. Not only does sexual activity provide pleasure for older adults, it may also help maintain a sense of usefulness and self-esteem, aspects of life often diminished after retirement. Sexual activity can help each partner express love, affection, and loyalty. It can also enhance personal growth, creativity, and communication. Older persons, especially older women, who feel desirable and attractive often feel younger as well (Messinger-Rapport, Sandhu, & Hujer, 2003). In the 2007 Lindau et al study, older adults regard sexual activity as an important part of life. Although the need to express sexuality continues among older adults, they face several barriers to sexual expression, including problems arising from low desire, aging, disease, and medications; societal beliefs; and changes in social circumstances (Lindau et al, 2007). Nurses are in a pivotal position to assess normal aging changes, along with those caused by disabling medical conditions and medications, and to intervene at an early point to enhance sexuality in older adults. The absence of male partners for older women propagates the stereotype that older adults should not participate in sexual relationships. The life span of men in the United States is shorter than that of women. In 2006, women accounted for 58% of the population age 65 or older and 68% of the population age 85 or older (Older Americans, 2008). This often leaves older women without sexual partners. The loss of a partner does not necessarily mean that the woman does not have continuing sexual needs. In a recent study, Lindau et al (2007) found that older women had a similar number of sexual concerns as younger women but were less likely to have the topic of sexual health raised during health care visits. It is imperative that health care professionals value the continuing sexual needs of older women as much as those of younger individuals and provide interventions for fulfilling sexuality. At times, such interventions might include increasing socialization for older women to assist them with finding new partners. Older adults may be reluctant to begin dating, feeling unfamiliar with dating practices. How to date and make new relationships can be challenging (Butler & Lewis, 2000). Alternatively, masturbation is a method in which both men and women can be sexually fulfilled in the absence of partners. Lindau et al found that the prevalence of masturbation was lower at older ages but higher among older men than older women (2007). Assisting older adults with masturbation may appear beyond a nurse’s ability; however, there are excellent references available within commercial bookstores to help older adults use this method to become sexually fulfilled. The literature has established that, in addition to older adults’ ongoing need to express their sexuality through traditional sexual methods, the human need to touch and to be touched must also be fulfilled. A person’s need for intimacy and closeness to another does not end at any age (Kaiser, 2000a, 2000b). There is little information about the role of touch as a substitute or addition to the sexual practices of older adults. It is known that touch is an overt expression of closeness, intimacy, and sexuality and is an integral part of sexuality. The importance of touch is often undervalued by society. In fact, touch is often thought of as the invasion of a person’s space, and caregivers should not assume that a person likes and wants to be touched (Rheaume & Mitty, 2008). Non–task-related “affective” touching, such as simply stroking a person’s check or holding their hand, may be viewed as assaultive, erotic, comforting, or presumptuous, depending on a person’s culture, personal comfort level, and relationship with the one touching (Rheaume & Mitty, 2008). For legal as well as privacy reasons, many people have shied away from touching. To older adults experiencing touch deprivation, the social rules that govern touch may be devastating. It is important to remember that touch is a way in which older adults may fulfill their sexuality with each other. Touch may be both a welcome addition to traditional sexual methods and an alternative means of sexual expression when intercourse is not desired or possible. Despite the continuing need for sexuality, older adults may have difficulty accepting and understanding their sexuality. Sexuality and sexual expression were not formally or informally taught during the developmental years of today’s cohort of older adults. In fact, sexuality was hidden behind closed doors for most of these older adults’ lives. Therefore the sexuality assessment of an older adult may be the first opportunity he or she has to openly discuss sexuality. Embarrassment, shyness, and apprehension in this area are common. In addition, the client may view the normal changes of aging as embarrassing or indicative of illness and may be reluctant to discuss these matters with a nurse. Some are misinformed about sexuality and may refuse to discuss sexual issues about which they harbor feelings of guilt and shame (Butler & Lewis, 2000; National Council on Aging, 1998). Understanding older adults’ attitudes and myths about aging will help the nurse assess and intervene to sensitively promote the expression of sexuality. The thought of older and often disabled people engaging in sexual intercourse is not appealing to society. Nurses often share society’s ageist beliefs about the asexuality of older adults, which can lead to nurses discouraging sexual activity (Messinger-Rapport et al, 2003). In long-term care settings, including assisted living facilities, a resident’s attempt at sexual expression is often viewed as a “problem” behavior (Rheaume & Mitty, 2008). In fact, more literature about the sexuality of older adults pertains to the inappropriateness of the behavior. Older adults face many barriers to sexual expression. NSHAP found that low desire (43%), difficulty with vaginal lubrication (39%), and inability to climax (39%) were the greatest barriers among women. Among men, erectile difficulties (37%) were the most prevalent barrier (Lindau et al, 2007). As a result of these factors, nurses have recoiled from venturing into such uncharted territory. The end result is that sexually interested older adults are in a situation in which they may have multiple disabilities, no privacy, no support, and no appropriate way in which to express their sexual feelings (Wallace, 2007). To assess sexual function in older adults, health care providers need to understand the sexual response cycle, which is a psychophysiologic cascade of events leading to orgasm (Wise & Crone, 2006). The two parts of the cycle include the desire phase and the arousal phase. Lowered levels of desire and hypersexuality are dysfunctions in the desire phase, and erectile dysfunction, vaginismus, and dyspareunia are dysfunctions in the arousal phase. In both genders the reduced availability of sex hormones in older adults results in less rapid and less extreme vascular responses to sexual arousal (Wise & Crone, 2006). Although some older adults view this gradual slowing as a decline in function, others do not consider it an impairment because it merely results in them taking more time to achieve orgasm (Butler & Lewis, 2000). Common physiologic changes associated with aging men are an erection that is less firm and shorter acting, less preejaculatory fluid, and semen that is less forceful at ejaculation (Butler & Lewis, 2000; Messinger-Rapport et al, 2003). The refractory period between ejaculations is long. Andropause (male menopause) has several physical, sexual, and emotional symptoms. There is disagreement about which term should be used to accurately describe the phenomenon. Most endocrinologists now use the term ADAM, an acronym for androgen decline in the aging male (Blackwell, 2006). A decline in the concentration of testosterone is believed to be the cause of andropause (Blackwell, 2006). Serum sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) concentrations gradually increase as a function of age, making less free testosterone. Testosterone levels diminish with age from a reduction in both testosterone production and metabolic clearance. These hormonal changes lead to a loss of libido, decreased muscle mass and strength, alterations in memory, diminished energy and well-being, an increase in sleep disturbance, and possibly osteoporosis secondary to a decrease in bone mass. Testosterone appears to influence the frequency of nocturnal erections; however, low testosterone levels do not affect erections produced by erotic stimuli (Kaiser, 2000a; Messinger-Rapport et al, 2003). Despite these physiologic changes, aging men can still experience orgasmic pleasure (Messinger-Rapport et al, 2003). An instrument such as the ADAM Questionnaire, created by Morley (2000), is a helpful screening tool that should prompt further workup, including determination of the testosterone level. Other laboratory studies should include a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and a prostate-specific antigen test (Blackwell, 2006). Erectile dysfunction (impotence), the inability to develop and sustain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse in 50% or more attempts at intercourse, can occur at any age but does increase with age (Araujo, Mohr, & McKinlay, 2004). Causes of erectile dysfunction include structural abnormalities of the penis, the adverse effects of drugs, psychologic disorders, and vascular, neurologic, and endocrine disorders. It is most common to have more than one cause of erectile dysfunction (Wise & Crone, 2006). Women usually do not have difficulty maintaining sexual function in older age unless a medical condition intervenes. The infrequency of sexual activity for older women is usually from their lack of desire, according to the NSHAP study. Most sexual changes occur with menopause, including atrophic vaginitis, with dryness of the vaginal mucosa leading to irritation or pain and bleeding during intercourse (Butler & Lewis, 2000; Messinger-Rapport et al, 2003). Urinary incontinence from detrusor insufficiency or stress can cause embarrassment during intercourse (Messinger-Rapport et al, 2003). The age-related shortening and narrowing of the vagina may further compromise pleasurable intercourse (Butler & Lewis, 2000). Women may also have increased facial hair from decreased estrogen levels, causing them to feel less attractive (Butler & Lewis, 2000). Libido appears to be testosterone dependent in both men and women. Women experience a decline in both ovarian hormones and adrenal androgens in the years preceding menopause. This can cause a diminished sense of well-being, loss of energy, loss of bone mass, and decrease or loss of libido (Kaiser, 2000b). Some of the causes of decreased libido include low bioavailable testosterone, elevated prolactin, and, indirectly, decreased estrogen. Incontinence can also decrease libido and inhibit arousal (Kaiser, 2000b). Dyspareunia, painful intercourse or pain with attempted intercourse, is a condition older women often experience, resulting in a decreased desire to participate in sexual activity. About one third of sexually active women older than the age of 65 experience dyspareunia. Causes of dyspareunia include inadequate vaginal lubrication, irritation and dryness of the external genitalia, urethritis, improper entry of the penis, anorectal disease, altered anatomy of the female genital tract, vulvovaginitis, local trauma (e.g., episiotomy scars), and even arthritis (Kaiser, 2000b). Vaginismus, involuntary painful contraction (spasm) of the lower vaginal muscles, is also often experienced by older women, again decreasing their desire to participate in sexual activity. Causes may be related to dyspareunia, vaginal infections, or vaginal mucosal irritation. It may be triggered by fear of losing control or of being hurt during intercourse (Kaiser, 2000b). Sexual function is a process that depends on the neurologic, endocrine, and vascular systems. It is also influenced by several psychosocial factors, including family and religious beliefs, the sexual partner, and the individual’s self-esteem (Wise & Crone, 2006). Several medical disorders common to older adults can affect sexual function (Box 13–1). Surgeries can also affect an older adult’s sexual responses. Some of theses surgeries include coronary artery bypass surgery, hysterectomy, mastectomy, prostatectomy, orchiectomy, and removal of the anus and the rectum. In addition, many drugs adversely affect sexuality (Table 13–1). TABLE 13–1 DRUGS ADVERSELY AFFECTING SEXUALITY Data from Messinger-Rapport B, Sandhu S, Hujer M: Sex and sexuality: is it over after 60? Clin Geriatr 11(10):45, 2003; Nusbaum M, Hamilton C, Lenahan P: Chronic illness and sexual functioning, Am Fam Phys 67:347, 2003; and Butler R, Lewis M: Sexuality. In Beers M, Berkow R, editors: The Merck manual of geriatrics, Rahway, NJ, 2000, Merck. Older adults continue to be a considerable proportion of the population infected by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Lovejoy & Heckman, 2008). According to the National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention’s 2007 statistics, those older than the age of 50 with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) represent 17% of all AIDS cases (National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, 2009). This is a 2% increase from 2002. Statistics indicate older adults are more likely than younger persons to develop AIDS less than 12 months after a diagnosis of HIV infection. The estimated number of new diagnoses of HIV/AIDS has also increased among adults older than 65 years of age, from 696 in 2004 to 803 in 2007, and has almost doubled from what it was 5 years ago (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009). • They see sexually transmitted disease (STD) as something that happens to somebody else because they were settled in marriages when the safe sex battles of the 1980s were raging. • Older women do not fear pregnancy because they are postmenopausal, so having the man wear a condom is not a concern. • Older women outnumber older men, which gives men many partners to choose from; therefore women try to please their male partners by agreeing to unprotected sex. • Older adults grew up when men made most of the decisions in a relationship; thus if a man does not want to use a condom, then it is not used.

Intimacy and Sexuality

Older Adults’ Sexual Needs

The Importance of Intimacy Among Older Adults

Nursing’s Reluctance to Manage the Sexuality of Older Adults

Normal Changes of the Aging Sexual Response

Orgasm

Pathologic Conditions Affecting Older Adults’ Sexual Responses

Illness, Surgery, and Medication

DRUG CLASS

EXAMPLE

EFFECT ON SEXUALITY

Dopamine agonists

Levodopa

Increased desire

Ropinirole hydrochloride (Requip)

Pramipexole dihydrochloride (Mirapex)

Pergolide mesylate (Permax)

Diuretics

Furosemide (Lasix)

Incontinence

Bumetanide (Bumex)

Spironolactone (Aldactone)

Anticholinergics

Tolterodine tartrate (Detrol)

Impaired ejaculation

Metoclopramide (Reglan)

Diphenhydramine (Benadryl)

Furosemide

Note: Many drugs have anticholingeric properties.

Antipsychotics

Risperidone (Risperdal)

Inhibited erection

Olanzapine (Zyprexa)

Inhibited ability to ejaculate, even when the capacity for erection remains

Sedatives-hypnotics

Zolpidem tartrate (Ambien)

Depressed sexual arousal

Temazepam (Restoril)

Antidepressants

Paroxetine hydrochloride (Paxil)

Fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac)

Antihypertensives

Hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ)

Erectile dysfunction

Spironolactone

Incontinence

Atenolol

Inhibition of orgasm

Clonidine

Lisinopril

Diltiazem hydrochloride (Cardizem)

Alcohol

Erectile dysfunction

Women’s sexual function

Antianxieties/benzodiazepines

Lorazepan (Ativan)

Decreased sexual desire

Alprazolam (Xanax)

Inhibition of orgasm

Anticonvulsants

Phenytoin (Dilantin)

Decreased desire

Carbamazepine (Tegretol)

Erectile dysfunction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Intimacy and Sexuality

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access