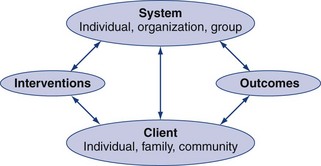

Chapter 23 Conceptual Models of Care Delivery Impact Brooten’s Advanced Practice Nurse Transitional Care Model Performance (Process) Improvement Activities Outcomes Management Activities Studies Comparing Advanced Practice Nurse and Physician and Other Provider Outcomes Studies Comparing Advanced Practice Nurse and Physician Productivity Studies Comparing Advanced Practice Nurse and Usual Practice Outcomes Summary of Advanced Practice Nursing Outcomes Research A number of factors have led to the current focus on outcomes of care in health care, including increased emphasis on providing quality care and promoting patient safety, regulatory requirements for health care entities to demonstrate care effectiveness, increased health system accountability and changes in the organization, delivery, and financing of health care. Advanced practice nurses (APNs) are affecting patient and system outcomes in a number of ways, but too often these outcomes are not quantified or attributed to advanced practice nursing. Employers, consumers, insurers, and others are calling for APNs to justify their contribution to health care and to demonstrate the value that they add to the system. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the future of nursing has highlighted the importance of promoting the ability of APNs to practice to the full extent of their education and training and to identify further nurses’ contributions to delivering high-quality care (IOM, 2010). Verifying APN contributions requires an assessment of the structures, processes, and outcomes associated with APN performance and the care delivery systems in which they practice. Outcomes evaluation and ongoing performance assessment are essential to the survival and success of advanced practice nursing. The importance of this dimension of advanced practice is highlighted repeatedly in the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice. Incorporated within each essential competency is a discussion of the need to evaluate the effect of APN action and decision making on care delivery outcome (AACN, 2006). A key rationale supporting the development of the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) degree has included industry demand for APNs capable of gauging baseline clinical outcomes, determining gaps in the use of evidence-based practice (EBP), masterfully leading change that is scientifically sound, and measuring the impact of their interventions. • Benchmark. A point of reference for comparison. Benchmarking is the process used to compare an individual’s (or organization’s) outcomes with those of high performers. It requires an assessment of the processes used by high-performing practitioners or organizations to achieve their outcomes, as well as the strategies and systems used to attain and then sustain performance excellence (Mathaisel, Cathcart, & Comm, 2004). Four phases are involved in the benchmarking process for APNs: (1) the conduct of a comprehensive self-assessment of current processes and outcomes of care, including comparisons of performance across internal departments and documentation of baseline data; (2) the identification of comparable providers whose outcomes are superior to those of the benchmarking APN; (3) an analysis of the differences between the processes used by the high performers and the benchmarking APN, with the establishment of goals for improved performance by the benchmarking practitioner; and (4) the implementation of best practice processes and the monitoring of results over time (DeLise & Leasure, 2001). • A performance benchmark is defined in health care as an ideal practice standard target that has been achieved by some group or organization known for its quality of services. This process-focused benchmark serves as the gold standard against which others are compared. Some evaluators also use this term to denote achievement of an intermediate outcome (e.g., attainment of desired best practice performance). • Comparative effectiveness research. Research evidence generated from studies that compare drugs, medical devices, tests, or ways to deliver health care. It is designed to inform health care decisions by providing evidence on the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of different treatment options (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2012). • Dashboard. A visual representation of data to enable the review, analysis, and tracking of data trends. The dashboard is like a score card because it allows for the visualization of performance and outcome information (U.S. Agency for International Development, 2010; U.S. Department of Education, 2011). • Disease management. An organized process focusing on the patient’s disease as the target of interest, with improvements in outcome seen as a result of attention to the attributes or characteristics of the disease. The intent is similar to outcomes management, which implements interventions to achieve a desired effect. The principal difference is the focus, with disease management directed at comprehensive monitoring and management of the patient’s underlying condition and outcomes management focused on measurement of the observed effects of treatment (Wojner, 2001). Quality indicators endorsed and adopted by federal and private health plans commonly target adherence to evidence-based processes that are expected to affect disease management. Program compliance with expected process performance is increasingly tied to pay for performance because of evidence demonstrating improved disease outcomes and cost containment. The medical home concept is tied closely to disease management principles and practice imperatives for the use of standardized evidence-based processes. The primary aim of medical homes is to oversee all health needs from prevention to disease management in one practice setting, thereby ensuring consistency of health strategies, accessibility to knowledgeable practitioners, and provision of seamless health services. Interestingly, reports of outcomes associated with medical homes are limited in the literature, although this model has been widely advocated as a method to improve and prevent disease (Grumbach & Grundy 2010). • Effectiveness. Extent to which interventions or actions taken in clinical settings perform as expected with defined populations (Armenian & Shapiro, 1998). Effectiveness assumes the generalizability of evidence-supported processes, suggesting that these methods may be replicated in clinical practice and will achieve the same results as demonstrated in clinical trials. The principle of effectiveness supports the adoption of standardized health care processes forming the basis for pay for performance core measures, because it assumes that widespread use of evidence-based methods will reduce disease and complication incidence, thus ultimately reducing health care costs. Program effectiveness refers to the measurement of the results attained through the systematic adoption of evidence-based structures (e.g., systems such as equipment, manpower) and standardized processes, whereas intervention effectiveness refers to the measurement of results in line with implementation of a specific EBP. Ultimately, effectiveness may translate into health care cost savings, but these savings may be remote from the systems and processes implemented. • Efficiency. The effects achieved by some intervention in relation to the effort expended in terms of money, resources, and time. In outcomes assessment, efficiency measures are used to compare two equally effective interventions (Hargreaves, Shumway, Hu, et al., 1998) and, for care providers, often include productivity considerations. In such cases, costs of care, treatment patterns, service volumes, and time required are usually compared (Armenian & Shapiro, 1998). • Evidence-based practice. Integration of research findings (evidence) into clinical decision making and care delivery processes. Best evidence for clinical practice is derived from methodologically sound research that is theory-derived, consistent with patient needs and preferences (Ingersoll, 2000), and clinically relevant to the population of interest. The findings of these investigations support and enhance the clinician’s clinical expertise; they do not replace it. This is particularly true for decisions concerning individual patients, in whom personal characteristics and circumstances may differ from those of the populations studied. When available, evidence-based information should be used in the selection of process of care measures (e.g., percentage of eligible acute myocardial infarction patients receiving aspirin at time of arrival to hospital). Evidence-based data are also useful in the development of practice guidelines, which are used to assist practitioners and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical care situations (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2012). Practice guidelines are systematically developed recommendations, strategies, or other information to assist health care decision making in specific clinical circumstances (AHRQ, 2010). The shift to pay for performance, based on the systematic implementation of EBP, provides an example of the power of scientifically sound processes and is driving practitioner viability in the health care market. • Impact measurement. An analysis of the difference in a targeted outcome measure and growth of practice systems resulting from use of the outcomes management process (Alexandrov & Brewer, 2010). Impact measurement enables APNs to showcase the effectiveness of programs implemented to improve patient outcomes. Analyzing the impact of an outcomes management process can help identify key aspects of a process that led to changes in an outcome (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HSS], Administration for Children and Families, 2010). • Metric. Also described as a measure or indicator, a metric defines parameters for structure, process, or outcome, depending on their level. For example, a metric for rate-based measures would define population numerators and denominators to ensure that each party using the metric measures the same population (validity) in the same way each time (reliability). The National Quality Forum (NQF) has defined criteria that should support all metrics to be submitted for endorsement by their agency, thereby making them eligible for pay for performance adoption by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other third-party payers. These criteria include the following: (1) the importance of studying the measures and publicly reporting findings; (2) the scientific acceptability of measure properties—that they measure validity and reliability; (3) usability, the extent to which payers, providers, and consumers can understand results and use them for health care decision making; and (4) feasibility, the extent to which the required data are available or could be captured without undue burden (NQF, 2012). • Outcome. The results of an intervention; changes in the recipient of an intervention. Measurement of outcomes will vary according to the intended recipient. For example, recipients may be patients, families, students, other care providers, communities and, in some cases, organizations (if the organization as a whole is the recipient of the intervention). Outcomes may be intended or unintended and reflect positive or untoward results, such as complications. Because of this, measurement plans must be cautiously developed to capture all outcomes (positive or negative) that theoretically align with the planned intervention, including the likelihood of no change in preintervention status (Alexandrov, 2008; Doran, 2011; Wojner, 2001). Most definitions of outcome have evolved from the original writings of Donabedian (1966, 1980), who defined an outcome as a change in a patient’s physiologic health state (i.e., morbidity and mortality). Later authors incorporated psychosocial changes (e.g., patient satisfaction, anxiety), acquisition of health-related knowledge, and health-related behavioral change as additional outcome dimensions (Bloch, 1975). This patient-centered understanding of outcomes is particularly relevant to APNs, whose actions directly or indirectly affect patients and families. • Outcome(s) assessment. An evaluation of the observed results of some action or intervention for recipients of services. Outcome assessments provide the data needed to support or refute the perceived beneficial effect of some clinical decision, care delivery process, or targeted action. • Outcome indicators, metrics, or measures. The results of interventions, including the use of new structures or processes on service recipients. Outcome indicators are derived from systematic determination of all potential results that could occur from a specific intervention or program; these measures should be clearly defined in terms of their measurement properties to ensure validity and reliability, with consideration of their temporal association to the intervention. For example, measure developers must consider whether an outcome should be measured immediately after an intervention, within 24 hours of an intervention, or more remotely, at several months postintervention. Often, surrogate intermediate outcomes that are theoretically in line with a targeted long-term outcome can be appropriately identified for measurement (Wojner, 2001). For example, arterial recannulization with IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in acute ischemic stroke is a surrogate intermediate outcome for disability reduction at 3 months (long-term outcome measure). Today, a variety of well-defined, tested, and endorsed outcome measures are available for use in outcome and disease management programs. Because the development of sound process and outcome measures requires extensive expertise and testing, APNs are encouraged to select NQF-endorsed measures to support many of their projects, because these are thoroughly established. This approach ensures consistency in the methods used to study and improve phenomena of interest. Outcome measures may be cross-cutting (applicable to any population or care delivery environment) or population-specific. Also, outcomes can be generic (applied to assess general concepts such as health status), or condition-specific, which are used to provide more accurate assessments related to a specific state, such as the impact of congestive heart failure on activity levels. APNs must make their contribution to health care improvement associated with selected outcome measures visible through their leadership of EBP projects and dissemination of their work. Intermediate outcome indicators are surrogate measures that are theoretically similar and measured proximally to a definitive target outcome (Wojner, 2001). These indicators may alert investigators to the likelihood of meeting a defined outcome target by demonstrating movement toward or away from outcome achievement. Intermediate indicators are most useful when the desired outcome is measured distal to an intervention or is multidimensional, such as outcomes associated with consecutive or cumulative protocols. • Outcome(s) management. Enhancement of outcomes, through development, implementation, and ongoing study of the impact of the interventions, actions, or process changes (Alexandrov, 2008; Wojner, 2001). According to the classic work of Ellwood (1988), a comprehensive outcomes management program does the following: (1) emphasizes the use of standards to select appropriate interventions; (2) measures a broad array of outcomes, including disease-specific, behavioral, functional, and perception of care outcomes; (3) pools outcomes data for groups of like patients in relation to processes of care and patient characteristics; and (4) analyzes and disseminates findings to stakeholders (patients, payers, providers) to inform decision making. The goal is to improve care to aggregate populations. • Outcome(s) measurement. The collection, analysis and reporting of reliable and valid outcome indicators. • Outcome(s) research or patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR). The use of the scientific method to measure the result of interventions on targeted patient health outcomes (Alexandrov & Brewer, 2010; Clancy & Collins, 2010). Outcomes research methods target examination of aggregate results in relation to changes in structure and processes. Comparative effectiveness research is the most rigorous form of PCOR, using rigorous randomized clinical trial designs to determine differences in treatment options; these studies provide the basis for fully informed patient decision making. • Performance (process) improvement. Activities designed to increase the quality of services provided. The focus of attention shifts to the actions taken by the provider rather than the outcomes achieved. Although outcomes may be monitored to determine whether the change in process produces a desired effect, primary attention is on the interventions (care delivery processes) delivered. Clearly linked with these actions is outcomes evaluation, which focuses on the impact of care delivery processes and the identification of areas of needed improvement. Subsumed within performance improvement activities are those associated with quality improvement initiatives, also described by some as continuous quality improvement (CQI) or total quality management (TQM). Although subtle distinctions are assigned to each of these terms, the focus and the intent are the same—to ensure the delivery of care that is appropriate, safe, competent, and timely and to maximize the potential for favorable patient outcomes. In most cases, the measurement of performance is guided by the use of established indicators of best practice, such as national guidelines for care. These performance indicators may be internally derived or externally developed by expert panels who use existing evidence to specify which indicators are most reasonable and which targets are most desirable for achievement. • Performance evaluation (assessment). Assessment of individual achievement and the attainment of personal, professional, and organizational goals. Performance assessment activities for APNs include those associated with evaluating and improving day to day interactions with individual patients and health care colleagues and those involving the measurement of APN impact on populations, organizations, and communities. During these self-assessment and peer- or supervisor-initiated reviews, areas for improvement are defined. These performance improvement activities may be directed toward technical skills enhancement, interpersonal style, productivity specifications, professional development, or other individual APN actions linked to improved processes of care or care delivery outcome. In this case, the focus is on the APN’s behaviors, with specific goals for improved performance identified for the upcoming quarter or year. • Process indicator, measure. A measure of visible behavior or action that a care provider undertakes to deliver care. Process indicators measure what care providers provide during their interactions with patients and are necessary for demonstrating a cause-and-effect relationship between intervention and outcome. The NQF has halted endorsement of process indicators defined purely by documentation of services provided, such as documentation of provision of smoking cessation counseling. APNs are encouraged to consider more robust measures, such as achievement of smoking cessation (an outcome measure), because documentation does not necessarily guarantee performance of a standardized service. • Program evaluation. Assessment of the quality of structure and processes within a system of care designed to serve a specific patient population. In most cases, program evaluations are designed to provide stakeholders with information about the overall costs in relation to program structure and processes, as well as the outcomes achieved from program services. Because APNs play an integral role in supporting programs, well-articulated APN services and visible APN leadership of program systems may be causally associated with program outcomes. • Proxy indicators. An indirect measure of some anticipated outcome used when a direct measure cannot be obtained or when an accurate indicator has not been identified. An example of a proxy indicator is the collection of self-report data from parents or spouses when patients are unable to respond to questions about perceptions of care or previous health. In the acute care hospital setting, case mix index, patient age, and comorbidity often are used as proxy indicators of risk adjustment for given clinical populations, simply because more direct indicators are not readily accessible. Length of stay has been a commonly measured proxy outcome but there are limitations to its use, because many factors can affect length of stay. • Quality of care. The degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with professional knowledge (IOM, 2001, p. 232). Quality of care is a dimension of the process and structure of care; it is not an outcome. Outcomes should be assessed in evaluating quality of care to provide an indication of the worthiness of health care structures and services. • Risk and severity adjustment. A process used to standardize groups according to characteristics that might unduly influence an outcome. For example, a past medical history of stroke may alter the ability to achieve a functional outcome in a group of patients when compared with patients with no history of stroke. Severity adjustment is typically disease-specific and based on physiologic findings that are specific to the disease entity (Wojner, 2001). An example of severity adjustment would involve standardizing a patient cohort according to their New York Heart Association Functional Classification in heart failure, which may affect resource use, cost of care, rehospitalization, functional status, and even mortality. The aim of risk and severity adjustment is to level the field among all patients in a sample, so that outcomes associated with interventions may be measured more accurately. • Standards. A profession’s authoritative statements that describe the responsibilities of its practitioners (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2010. Standards define the boundaries and essential elements of practice and link practitioners’ care, quality, and competence through their delineation of required elements of practice (Dozier, 1998). They also serve as a criterion for the establishment of practice-related rules, conditions, and performance requirements. Standards focus on the processes of care delivery. • Structural indicators. Measures of human, technical, and other resources used in the process of delivering care. These structures focus on the characteristics of the setting, system, or care providers and include such elements as numbers and types of providers, provider qualifications, agency policies and procedures, characteristics of patients served, and payment sources. Examples of structural indicators are the ratio of registered nurses (RNs) or APNs to total nursing staff, nurse-to-patient ratio, nursing care hours per patient day, nursing injury rates, and attrition rates. The assumption underlying these measures is that the provision of adequate structures results in adequate outcomes. Although structural indicators provide important information about the impact of APN practice, they cannot stand alone. Measurement of the full range of APN effect also may be hampered by the organizational or clinician’s philosophy underlying the care delivery process. For example, Murphy and Fullerton (2001) have noted that a hallmark of midwifery practice is the “advocacy of non-intervention in the absence of complications” (p. 274). Measuring this advocacy process is difficult and relating it to observed care delivery outcomes is even harder. Similarly, linking noninterventions to outcomes is also a challenge. Much of the difficulty associated with measuring APN impact can be minimized through the use of a conceptual model to guide assessment and monitoring activities. A number of outcomes measurement and role impact models have been proposed, with several of these evolving from an original quality of care framework proposed by Donabedian (1966, 1980). Donabedian posited that quality is a function of the structural elements of the setting in which care is provided, processes used by care providers, and changes to the recipients of care (i.e., the outcomes). Applying these concepts to APN practice, structural variables relate to the components of a system of care. Process variables pertain to the behavior or actions of the APN or the activities of an APN-directed educational or care delivery program. Interactions among structures and processes result in outcomes. Structure, process, and outcome variables can be studied independently or as a model for overall APN practice. The more complete the model (e.g., the inclusion of all or at least two of the components), the more likely is the successful identification of the APN’s impact on care delivery outcome. Two models will be described. This Donabedian-guided model, a classic outcomes evaluation model, was designed by Holzemer (1994) and adapted by others (Cohen, Saylor, Holzemer, et al., 2000; Radwin, 2002; Wong, Stewart, & Gilliss, 2000). The value of this model is its program planning structure, which helps identify essential components of any outcomes evaluation plan (Table 23-1). In Holzemer’s model, essential outcomes measurement components are defined in a table consisting of inputs-context (structure), processes, and outcomes, which are identified along the horizontal axis. Advanced Practice Nurse Outcomes Planning Grid* *Components are not exhaustive of APN-related outcomes planning but serve as a guide for planning activities. Adapted from Holzemer, W.L. (1994). The impact of nursing care in Latin America and the Caribbean: A focus on outcomes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20, 5–12. For the APN, the patient is any recipient of APN services (e.g., patients, families). The provider is the person (APN) or interdisciplinary group providing the service and potentially could include trained community laypersons who assist with the provision of services. The setting is the local environment in which the services are delivered and includes the resources available to provide care. Table 23-1 contains an application of Holzemer’s (1994) model to APN outcomes assessment planning. Included in the table are potential variables that may facilitate assessment of the APN’s impact. Additional variables would be selected based on specialty service, population specifics, and additional characteristics of the provider, patient, or environment. For APNs involved in quality improvement, the quality health outcomes model (QHOM; Fig. 23-1) is particularly relevant (Mitchell, Ferketich, & Jennings, 1998). This model provides a structure for studying complex relationships among patient, provider, and system level variables. As a result, studies guided by the model may better inform our understanding of patient outcomes. It focuses on the individual, organizational, and group dimensions of the health care system that influence and are influenced by care delivery interventions and outcomes and defines the patient as the individual, family, or community receiving the care provider’s services. FIG 23-1 Quality health outcomes model (QHOM). This model proposes two-direction relationships among components, with interventions always acting through characteristics of the system and patient. (From Mitchell, P. H., Ferketich, S., & Jennings, B. M. [1998]. Quality health outcomes model. American Academy of Nursing Expert Panel on Quality Health Care. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 30, 43–46.) Mitchell and colleagues’ model (1998) extended Holzemer’s work (1994) by suggesting that the relationships between model components are reciprocal and that interventions never affect outcomes directly but do so through their interactions with the system and patient. Thus, all assessments of APN impact must include information about the system and individual targeted for the intervention. By proposing a model that allows for multiple inputs at the level of patient, personnel, and system, the authors suggested that the model allows evaluators to analyze the contribution of specific variables to patient outcomes. Because the model incorporates organizational and system level influences, it can guide studies of system level interventions such as program initiatives or reimbursement changes, the results of which can be used to influence health policy. Sidani and Irvine (1999) have proposed a conceptual model designed to facilitate the evaluation of the acute care nurse practitioner (ACNP) role in acute care settings (Fig. 23-2). Developed in Canada, this model was adapted from a nursing role effectiveness model and is also a derivative of Donabedian’s framework, with components focusing on structure (patient, ACNP, and organization), process (ACNP role components, role enactment, and role functions) and outcome (goals and expectations of the ACNP role). A concern with this model is the use of the term goals and expectations for outcome and the focus on quality of care, which is a dimension of care delivery process rather than outcome. Four processes (mechanisms) within the ACNP direct care component are expected to achieve patient and cost outcomes: (1) providing comprehensive care; (2) ensuring continuity of care; (3) coordinating services; and (4) providing care in a timely way (Sidani & Irvine, 1999). According to this model, the selection of outcome indicators is guided by the role and functions assumed by the ACNP, how the role is enacted, and the ACNP’s particular practice model. Like the models before it, the usefulness of this framework for determining APN impact is limited by its virtual absence of testing in clinical settings. A review of the literature suggests that increased attention is being given to the assessment of APN performance. Several recent synthesis reviews highlighted that a number of studies had been conducted that focused on the evaluation of APN roles and on the outcomes of APN care (Hatem, Sandall, Devane, et al., 2009; Newhouse, Weiner, Stanik-Hutt, et al., 2011; Reeves, Hermens, Braspenning, et al., 2009). These focused on all APN roles, including nurse practitioner (NP), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), and certified nurse midwife (CNM) care and included two Cochrane Database reviews on the impact of primary care NPs (Reeves et al., 2009) and CNM care (Hatem et al., 2009). Before the 1990s, most reports of APN performance were descriptive in nature, with limited use of the experimental or quasi-experimental designs that allow for comparisons across studies. In a meta-analysis of nurse practitioner (NP) and CNM performance in primary care, Brown and Grimes (1995) identified 210 studies pertaining to NPs and CNMs. Of this number, only 53 met study inclusion criteria, which required evidence of NP or CNM intervention, data from patients in the United States or Canada, presence of a control group, measures pertaining to the process of care or clinical outcome, use of an experimental or quasi-experimental design, and data availability to support the calculation of effect size to determine the magnitude of the effect. Outcome indicators varied across studies and cause-and-effect relationships between type of care provider (APN or physician) and outcomes observed were not substantiated. Outcomes measured for NPs reflected more generic indicators of provider impact (e.g., patient compliance, patient satisfaction, functional status, use of the emergency department [ED]), whereas CNM outcomes were more reflective of specialized practice and included number of cesarean sections, spontaneous vaginal deliveries, incidence of fetal distress, birth weight, and 1-minute Apgar scores. Findings suggested that NPs requested more laboratory testing than physicians and had more favorable outcomes pertaining to patient satisfaction, health promotion behaviors, time spent with patients, and number of hospitalizations. CNMs used less anesthesia, analgesia, IV fluids, and fetal monitoring and performed fewer episiotomies, forceps deliveries, and amniotomies. Their patients also were more likely to have spontaneous vaginal deliveries, although these were accompanied by an increased number of perineal lacerations. A recent systematic review of 11 studies comparing care provided by midwives found that women who had midwife-led models of care were less likely to experience adverse events, including antenatal hospitalization, regional analgesia episiotomy, and instrumental delivery, and were more likely to experience spontaneous vaginal birth and initiate breast-feeding, among other findings (Hatem et al., 2009). Most recently, a synthesis review of the research conducted between 1990 and 2008 on the outcomes of APN care focused on comparing APN care with that of other providers (e.g., physicians, teams with APNs); this study identified that care provided by APNs has been demonstrated to affect outcomes positively (Newhouse et al., 2011). Of 107 studies focused on APN care in NP, CNS, CNM, and CRNA roles, substantial evidence demonstrated that APNs provide effective and high-quality care. The results of the review noted that care provided by NPs and CNMs in collaboration with physicians were similar, and in some ways better, than care provided by physicians alone, including lower rates of cesarean section deliveries, less epidural use and episiotomy rates, and higher breast-feeding rates for CNM patients and more effective blood glucose and serum lipid level control for NP-managed patients. The studies relating to CNS care demonstrated a decrease in length of stay and costs of care and high ratings of satisfaction for hospitalized patients. Studies relating to CRNA care, although few in number and observational in design, did suggest equivalent complication rates and mortality when comparing care involving CRNAs with care involving only physicians. The largest number of studies related to NP care; these included 37 studies with 14 randomized control trials and 23 observational studies. A high degree of evidence was found for NP care related to improving patient satisfaction, patient self-assessed health status, blood pressure control, duration of mechanical ventilation, and similar rates of ED visits and hospital readmissions in NP and MD comparison groups (Newhouse et al., 2011). Role description studies focus on defining and describing role components and job attributes of APNs. These foundational studies assist in identifying the direct and indirect APN actions that potentially influence care delivery outcome. As such, they provide information about the structure or process components of Donabedian’s model (1966, 1980). Without information about the outcomes associated with the characteristics and role behaviors identified in these studies, however, little can be said about their impact on patient care. What these studies provide is evidence to guide the development of theories about which characteristics of APN practice or aspects of the APN role contribute to care delivery outcome. For example, does the APN’s expert coaching or collaboration processes contribute to more favorable outcomes when compared with care providers whose use of these processes is less apparent? Role description studies have explored the role and patient characteristics of APN practices in a variety of specialty-based roles, including psychiatric mental health (Hanrahan et al., 2011), acute pain services (Musclow, Sawhney, & Watt-Watson, 2002), neurovascular care (Alexandrov et al., 2009, 2010; Sung et al., 2011; Wojner, 2001), urology care (Albers-Heitner et al., 2012), asthma care (Borgmeyer et al., 2008), Alzheimer’s disease care (Callahan et al., 2006), geriatric care management (Counsell et al., 2007; Kane et al., 2004), cardiovascular care (Gawlinski et al., 2009; Lowery 2012), osteoporosis care (Greene & Dell, 2010), colorectal care (MacFarlane et al., 2011), oncology care (Cooper, 2009), cystic fibrosis care (Rideout, 2007), eczema care (Schuttelaar, Vermeulen, & Coenraads 2011), and nurse-managed clinics (Pohl et al., 2011), among others. APN activities have been directed primarily toward the oversight and management of patients’ needs, followed by administration, teaching, research, program development, and process improvement. APN roles also have been explored in a grounded theory study by Ball and Cox (2003), who interviewed 39 CNSs, NPs, consultants, and coordinators from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. The investigators identified three strategic activities that APNs believe contribute to restoring patients’ health, defined as improving patient care, continuity of care, and patient education. These activities, in combination with one another, are expected to prepare patients for transition (to home or independence) to produce high levels of satisfaction with service and enable independence through a clear understanding of illness and health-promoting behaviors. Overall perception of APN performance has been favorable, with most care providers and patients rating the performance and contribution of APNs highly (Allen & Fabri, 2005; Gooden & Jackson, 2004; Johantgen et al., 2012; Mitchell, Dixon, Freeman, et al., 2001; Newhouse et al., 2011). Hardie and Leary (2010) have explored patient perceptions of the value of a CNS in a breast cancer clinic. A questionnaire was given to 50 patients over a 6-week period in May 2007 (pre-CNS survey) and 1 year later (post-CNS survey) to 32 of the original patients. The survey results demonstrated that the CNS improved respondents’ experience and satisfaction with the breast cancer service. APN role receptivity studies also have explored physician acceptance of specialized diagnostic screening and invasive interventions by APNs. In a study of skin cancer screening, from 60% to 70% of family physicians and internists were supportive of NP screening (Oliveria, Altman, Christos, et al., 2002). Similar findings were noted for the acceptance of NP and CNM involvement in medical abortions (Beckman, Harvey, & Satre, 2002). A phenomenologic design was used to assess families’ perceptions of the essence of neonatal NP (NNP) care (Beal & Quinn, 2002). Themes identified included being positive and reassuring, being present, caring, translating information, and making parents feel at ease. In this same study, expert practitioner ability was identified as an expectation that families had of all care providers, regardless of background (medical or nursing) or level of practice (staff nurse or APN). Expectations for the NNP focused on interpersonal style and effectiveness of interactions with families. An important pragmatic implication of this study’s findings is the potential difficulty in placing a dollar amount on APN behavior. Because much of health care practice is reimbursement-driven, intangible provider attributes such as interpersonal competence often go unrecognized or are disregarded in provider payment decisions. This is a serious concern because patient and family perceptions of intangible processes often influence overall impressions of care delivery experience and may contribute to more tangible outcomes. Studies evaluating care delivery processes often occur in combination with role definition research. The distinction between these studies and role definition explorations is their attention to what APNs do as part of their roles. Examples include the delivery of preventive services (Becker et al., 2005; Carroll, Robinson, Buselli, et al., 2001; Counsell et al., 2007; Johnson, 2000; Sheahan, 2000; Windorski & Kalb, 2002; Zapka et al., 2000), inclusion of alternative treatments in care delivery processes (Sohn & Cook, 2002), management of ED patients (Lamirel et al., 2011), ordering of antibiotics (Goolsby, 2007), diagnostic tests, and invasive and noninvasive procedures (Cole & Ramirez, 2000; Sole, Hunkar-Huie, Schiller, et al., 2001; Venning, Durie, Roland, et al., 2000), inclusion of physical activity and physical fitness counseling in primary care practices (Buchholz & Purath, 2007), and the use of collaboration in caring for high-risk patients (Brooten et al., 2005). In these descriptive studies, information is provided about the direct and indirect actions taken by APNs during the delivery of care. No statements can be made about the relationships between any of these processes and care delivery outcomes, however, although some hypotheses can be proposed based on study findings. As a result, these studies are useful as a preliminary step toward outcomes assessment. In some studies, APN care delivery processes were compared with those of physicians and other care providers. These studies generally examined NP care and have found that NPs are more likely than physicians and other community health providers to spend more time with patients (Seale, Anderson, & Kinnersley, 2005; Venning et al., 2000), nursing staff, and other disciplines (Hoffman, Tasota, Scharfenberg, et al., 2003); informally manage patient care needs (Sidani et al., 2006a, 2006b); discuss treatment options (Seale, Anderson, & Kinnersley, 2006); and discuss and encourage smoking cessation (Sheahan, 2000; Zapka et al., 2000), although this prevention-focused activity may not extend to other health risks (Sheahan, 2000). No differences were seen for the treatment of febrile infants (Badger, Lookinland, Tiedeman, et al., 2002) or the timing and initiation of collaborative action to discuss patient concerns (Brooten et al., 2005). In one study, NPs were more likely to provide structural support for the emergency management of closed musculoskeletal injuries, although other interventions were similar to those of physician providers (Ball, Walton, & Hawes, 2007). In another study, residents spent significantly more time on coordination of care than NPs (Sidani et al., 2006a, 2006b). It is interesting to note that despite this difference, patients managed by NPs reported higher levels of coordination than those overseen by residents. Other process-focused studies have focused on CNM visit scheduling (Walker et al., 2002) and communication styles between CNMs and physicians, with both groups using informational styles during interactions with patients (Lawson, 2002). Intra-individual differences were noted for the CNM providers, however, suggesting that they changed to a more controlling communication style with certain patients. Contrary to the researcher’s expectations, communication style was not related to patient-perceived support for autonomy or patient satisfaction. Process-focused studies also have explored APNs’ use of clinical practice guidelines during the management of symptoms in oncology patients (Cunningham, 2006), NP health counseling behaviors (Lin, Gebbie, Fullilove, et al., 2004), and prescriptive writing patterns (Shell, 2001). Older studies provide clear evidence to counter early concerns about the potential for NPs to overprescribe (Campbell, Musil, & Zauszniewski, 1998; Hamric, Lindebak, Worley, et al., 1998). In one study of mental health NPs, however, an analysis of prescribing patterns for managing depression suggested that the NPs overused drugs considered less desirable, discontinued medications prematurely, and minimized important patient characteristics such as age when prescribing (Shell, 2001). Other studies have examined clinical practice guideline use, demonstrating increased compliance of NP-led initiatives (Gracias, Sicoutris, Stawicki, et al., 2008). These process-focused investigations highlight some of the APN activities that are expected to contribute to care delivery outcome. Because most of the studies did not assess the relationship between process of care and any specific outcome, however, little is known about the actual impact of these actions on recipients of care. Qualitative-focused work examining the processes of care have helped identify some characteristics of APN care, including the impact on care coordination and patient and family knowledge (Fry, 2011). In a qualitative study describing barriers and facilitators to implementing a transitional care intervention for cognitively impaired older adults and their caregivers led by APNs, identified themes included patients and caregivers having the necessary information and knowledge, care coordination, and caregiver experience (Bradway, Trotta, Bixby, et al., 2012). Additional studies are needed to highlight the impact of APN-led care that is unique to various APN roles to demonstrate further the unique features of APN care that affect patient and health care outcomes. Information about the relationship between APN care and patient outcomes has been demonstrated through a series of studies using a model of comprehensive discharge planning, early discharge, and home follow-up provided by APNs, as described by Brooten and colleagues (Brooten, et al., 2002a; Brooten, et al., 2002b; Brooten, et al., 2003; Brooten, et al., 2005). (Most of these studies used CNSs, although later reports by these authors used the generic term APN.) This care delivery model has been tested with high-risk, childbearing women (York, et al., 1997), older postsurgical cancer patients (McCorkle, et al., 2000), and older adults (Naylor, Brooten, Campbell, et al., 1999). In each of these studies, a randomized controlled clinical trial design was used to compare CNS outcomes with those seen with usual care. In all cases, outcomes were superior for the CNS intervention groups. McCorkle and colleagues’ study (2000) was particularly noteworthy because of the finding that the APN-led intervention significantly improved patient survival as compared with the control group receiving usual care. Cost of care for CNS-directed services was 44% less than for standard care (York, et al., 1997). Most of the cost savings for the older adult group were the result of a significant reduction in the number of readmissions for APN-managed patients (Naylor & Kirtzman, 2010; Naylor, Bowles, McCauley, et al., 2011), very-low–birthweight infants (Brooten, Gennaro, Knapp, et al., 2002a), women with unplanned cesarean birth, high-risk pregnancy, and hysterectomy, and older adults with cardiac diagnoses (Brooten, Youngblut, Deatrick, et al., 2003). During each of these studies, protocols were used to guide APN care delivery; APNs also recorded what was done during their interventions, the number of patient contacts made, the time spent during contacts, patient outcomes, and health care costs. In the study of mothers and infants, most of the APNs’ time was spent on assessment activities (69%), with the remaining time devoted to interventions (Brooten, Gennaro, Knapp, et al., 2002a). Assessments of infants focused on physical status, whereas assessments of mothers were directed at coping, health care, availability of support systems, and home environment. Assessments of mothers also addressed caretaking skills, understanding of procedures and medications, knowledge of infant growth and development, and recognition and prevention of infection. Intervention activities were devoted primarily to teaching, followed by liaison or consultation and encouragement of self- or infant care. In the combined analysis, surveillance was identified as the most common intervention, with APNs spending the greatest amount of time on monitoring signs and symptoms of physical problems (Brooten, et al., 2003). An important finding of this second analysis was the relationship between the magnitude of APN interaction and improvement in patient and cost outcomes. The longer the time spent by the APN, the better the outcomes. A second important finding was the difference in outcomes seen and the amount of APN involvement required across patient populations. This finding reinforces the importance of carefully describing the makeup of the patient population and care delivery setting (both of which are contextual or structural components of the quality of care framework), and the processes of care when measuring APN impact. Without this information, Brooten and colleagues (Brooten, et al., 2003; Brooten, et al., 2005) might have erroneously concluded that some APNs performed better than others, when in fact the differences were the result of patient condition and need. The APN transitional care model is a well-acknowledged framework; the significant research that has resulted on the impact of APN transitional care is a frequently cited body of work (Naylor & Kirtzman, 2010; Naylor, Bowles, McCauley, et al., 2011). Although no conclusion can be made about which of the APNs’ activities contributed specifically to the favorable outcomes seen, the inclusion of a process assessment component provides a preliminary indication of a cause and effect relationship between APN practice and patient outcome. Ongoing research on the model continues because additional research is needed to determine whether selected aspects of the process are more important or if favorable outcomes are achieved only through a combination of APN actions.

Integrative Review of Outcomes and Performance Improvement Research on Advanced Practice Nursing

Review of Terms

Conceptual Models of Care Delivery Impact

Models for Evaluating Outcomes Achieved by Advanced Practice Nurses

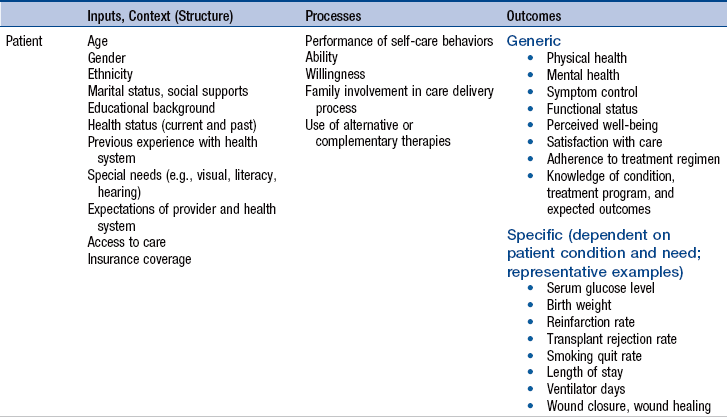

Outcomes Evaluation Model

![]() TABLE 23-1

TABLE 23-1

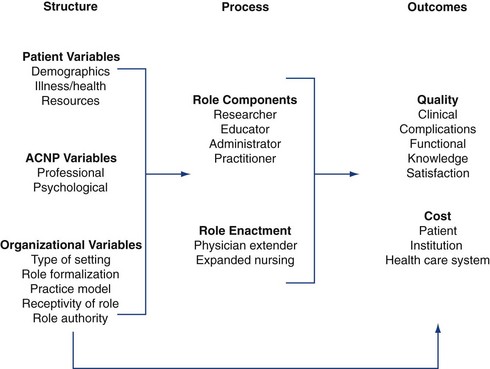

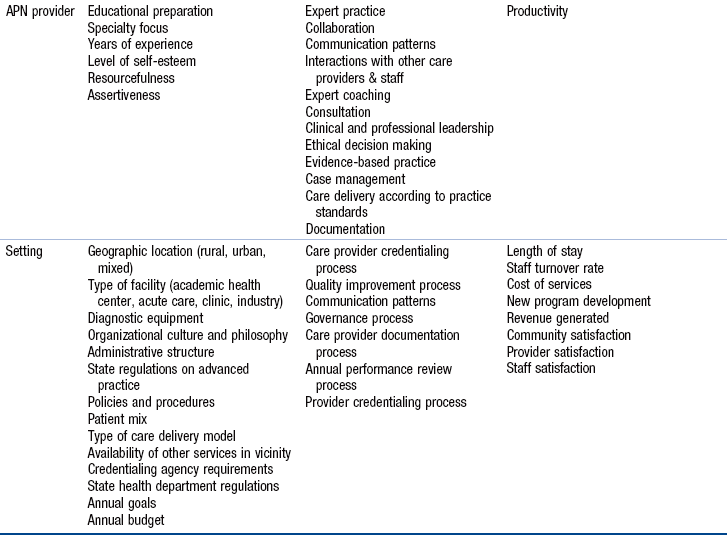

Nurse Practitioner Role Effectiveness Model

Evidence to Date

Role Description Studies

Role Perception and Acceptance Studies

Care Delivery Process Studies

Brooten’s Advanced Practice Nurse Transitional Care Model

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree