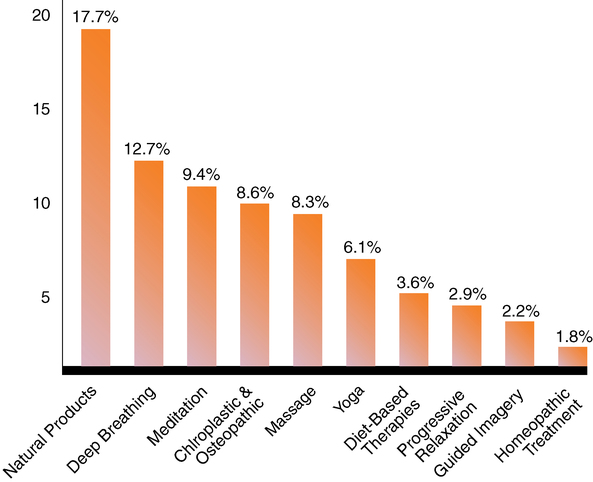

CHAPTER 35 Laura Cox Dzurec and Rothlyn P. Zahourek 1. Define the terms integrative care and complementary and alternative medicine. 2. Identify trends in the use of nonconventional health treatments and practices. 3. Explore the category of alternative medical systems along the domains of integrative care: natural products, mind and body approaches, manipulative and body-based practices, and other therapies. 4. Discuss the techniques used in major complementary therapies and potential applications to psychiatric mental health nursing practice. 5. Discuss how to educate the public in the safe use of integrative modalities and in the avoidance of false claims and fraud related to the use of alternative and complementary therapies. 6. Explore informational resources available through literature and online sources. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Integrative care places the patient at the center of care, focuses on prevention and wellness, and attends to the patient’s physical, mental, and spiritual needs (Institute of Medicine, 2009). Many of the philosophical underpinnings for the approaches presented in this chapter are derived from non-Western cultural traditions or from quantum physics and studies in the nature of energy and reality. The trend toward adoption and use of integrative care modalities in Western health care is fairly recent and, over time, has been influenced by changes in dominant scientific theory and belief (Weldon, 2011). Across its individual therapies, integrative care is directed at healing, and its practitioners consider the whole person (mind, body, and spirit), along with the lifestyle of the person in their choice of treatment options. Establishing a therapeutic nurse/patient relationship is integral to integrative care, which includes both conventional and alternative therapies as required by the individual patient or client. Clinicians may choose to use integrative care as a substitute for, or combined with, conventional therapies or treatments. Due to the growing interest in and use of CAM in the United States, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) in 1998, making it one of 27 institutes and centers of the NIH. The NCCAM supports fair, evidence-based, scientific evaluation of integrative therapies and the dissemination of information to assist health care providers in making relatively informed choices regarding the safety and appropriateness of CAM. Since 2000, NCCAM has been awarded $2 billion for research, and as of 2011, NCCAM’s annual budget was $134 million. In 2011, NCCAM released a set of goals and objectives intended to benchmark its research priorities through 2015 in a document called Exploring the Science of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Third Strategic Plan 2011–2015. Through this plan, NCCAM describes how it proposes to direct funding for research in complementary and alternative medicine for the next 5 years. The document addresses the conduct of research and the strengths and limitations of the scientific method for determining how CAM is used. What is clear in regard to CAM is that it is being used. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health Interview Survey included 31,000 people. They were surveyed regarding their use of 26 complementary and alternative treatments (Barnes et al., 2008). Below is a summary of the survey”s findings: • About 38% of adults (up from 36% in 2002) and almost 12% of children in the United States use some type of CAM. • Use of CAM by adults is greater among women and those with higher levels of education and higher incomes. • The most commonly used therapies are nonvitamin, nonmineral products such as fish oil/omega 3, glucosamine, echinacea, and flaxseed. • Adults are most likely to use CAM for musculoskeletal problems such as back, neck, or joint pain. • The use of CAM therapies for head or chest colds showed a substantial decrease from 2002 to 2007. Despite debates surrounding its efficacy, CAM has been steadily integrated into Western health care practice since 2002. This increased use may be due to a greater availability of CAM-prepared practitioners and practice facilities, along with more public exposure to CAM through the media. Box 35-1 lists the types of CAM included in the 2007 National Health Interview Survey, and Figure 35-1 is a graph comparing the 10 most commonly used therapies among adults surveyed. As noted, although research on the efficacy of CAM is increasing, studies in the field are minimal and often controversial when compared to those of conventional medicine. At issue is not only the comparison of traditional and alternative therapies but also the question of what actually counts as evidence to support their use (Walach, 2009). Numerous explanations contribute to the current complexity of CAM research and knowledge, including (1) the relatively recent use of some of these therapies in the United States, (2) lack of financial incentive to support the research, (3) difficulties encountered by researchers when studying these modalities (Box 35-2), (4) the evolution of complementary science in the Western world (Weldon, 2011), and (5) the eagerness with which the public has begun to embrace these modalities. Incorporation of CAM into Western health care practice has required a significant change in the way providers and researchers think about CAM. There has been a paradigm shift, or a major change, in the way that people think about things. This paradigm shift has instigated dramatic change in regard to perceptions of the legitimacy of nontraditional approaches to health care (van der Riet, 2011). CAM is being explored for such diverse and serious problems as neurocognitive disorders, substance abuse treatment, depression, traumatic life events, negative affect, trauma, pain, cancer, and diabetes (Edwards, 2012; Denneson, 2011). Reflexology, body work, prayer, visualization, breathing meditation, chiropractic, diet and/or megavitamin therapy, relaxation, massage, and poetry are among the CAM methods that are widely used. Consumers are attracted to integrative care for a variety of reasons, including the following: • A desire to actively participate in their health care and engage in holistic practices that can promote health and healing • A desire to find therapeutic approaches that seem to carry lower risks than traditionally used medications • A desire to find less expensive alternatives to high-cost conventional care • Positive experiences with holistic, integrative CAM practitioners, whose approach to patients is supportive and inclusive • Dissatisfaction with the practice style of conventional medicine (e.g., rushed office visits, short hospital stays) • A need to find modalities and remedies that provide comfort for chronic conditions for which no conventional medical cure exists, such as anxiety, chronic pain, and depression. Strong claims often are made on behalf of CAM therapies and modalities. One of the most common marketing angles is to use the term “natural” (Chiappedi, 2010). “Natural” emphasizes the notion that the chemicals in these medications are present in nature. Through its simplicity, the notion of “naturalness” suggests that alternative medications are harmless. However, even if they are naturally occurring, the chemicals contained in alternative medicines remain chemicals. The body does not distinguish between naturally occurring chemicals and those synthesized in a laboratory. Some natural substances are just not safe. Consider arsenic, for example, which is abundant in nature. Knowledgeable consumers, relying on health information available through public libraries, popular bookstores, and the Internet, may question providers about aspects of conventional health care. Nurses’ knowledge about CAM modalities and their commitment to ongoing evaluation of related evidence regarding the effectiveness of these modalities will provide information to patients and support general awareness of the efficacy of CAM in health care practice. For example, consumers are using herbal remedies to treat a variety of psychiatric conditions, including depression, which is among the most common complaints of all patients seeking medical treatment (Blues Busters, 2011). The wide range of herbs used without the guidance of a knowledgeable practitioner can result in serious side effects through their direct influence on the body and through interactions with other herbs and drugs. Nurses’ roles in collecting good assessment data about the integrative therapies their patients are using cannot be overemphasized; further, helping consumers actively evaluate the quality of information available to them is important. Information broadly available to consumers through sources such as the Internet and other readily accessible sources may not be especially useful or accurate (Evans et al., 2011). The American Nurses Association (ANA) recognizes holistic nursing as a specialty, publishing Holistic Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice in 2007. Holistic nursing is defined as “all nursing that has healing the whole person as its goal” (AHNA, 1998). Holism is described as involving (1) the identification of the interrelationships of the bio-psycho-social-spiritual dimensions of the person, recognizing that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and (2) understanding of the individual as a unitary whole in mutual process with the environment (AHNA, 2004). Holistic nursing accepts both views and believes that the goals of nursing can be achieved within either framework. Holistic assessments include the traditional areas of inquiry such as history, present illness, family medical history, and history of surgeries as well as medications taken and response to these medications; however, the holistic-integrative assessment also includes areas such as the quality of social relationships, the meaning of work, the impact of major stressors in the person’s life, strategies used to cope with stress (including relaxation, meditation, deep breathing, etc.), and the importance of spirituality and religion and cultural values in the person’s life. Patients also are asked what they really love, how this is manifested in their lives, what their strengths are, and to identify the personal gifts they bring to the world (Maizes et al., 2003). Integrative care is classified according to a general approach to care and is separated into these domains: (1) natural products, (2) mind and body approaches, (3) manipulative practices, (4) body-based practices, and (5) other CAM therapies (NCCAM, 2011). Some CAM therapies may fit into more than one domain. There is a good deal of study of the influence of diet and nutrition on health (Simpson et al., 2011). It is important that clinicians assess for patients’ use of nutrients such as vitamins, protein supplements, herbal preparations, enzymes, and hormones that are considered dietary supplements. These dietary supplements are sold without the premarketing safety evaluations required of new food ingredients. Dietary supplements can be labeled with certain health claims if they meet published requirements of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). They also may be labeled with a disclaimer saying that the supplement has not been evaluated by the FDA and is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. Clinicians and consumers both should know, however, that the FDA does not regulate supplements and that claims offered on supplement labels may or may not be accurate. Avoiding artificial food coloring became popular in the 1970s for treating children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other developmental disorders. The Food and Drug Administration long ago determined that there is no definitive link between these disorders and food dyes; however, some clinicians and parents believe that children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder are vulnerable to synthetic color additives (Food and Drug Administration, 2011). The efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids continues to be studied in the treatment of depression and bipolar depression. In a meta-analysis of studies of omega-3 supplements, Eisenberg and colleagues (2006) concluded that they could recommend them as adjuncts to standard treatment for depression and bipolar disorder. Chiu and colleagues (2008) reviewed epidemiological evidence, preclinical trials, and case-controlled studies on the use of omega-3 fatty acids and recommend that patients with depression and bipolar depression follow the same guidelines as for the American Heart Association. These stipulate that adults eat fish at least twice a week. Some authors (Chiu et al., 2008) argue that patients with mood disorders, impulse-control disorders, and psychotic disorders should consume 1 gram of omega-3 fatty acids a day. Certain nutritional supplements, including S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) and the B vitamins (especially vitamin B6 and folic acid), also appear to improve depression (Lakhan & Vieira, 2008). Currently, B vitamins and folic acid are also being seen more favorably for the management of bipolar illness and schizophrenia. According to Lake (2006), these vitamins often augment conventional care with antipsychotic, antidepressant, and antimanic medications. The researchers recommend that combining such approaches with exercise and meditative practices such as yoga is helpful. In a recent random, controlled trial investigating vitamins B12 and B6 and folic acid for the onset of depressive symptoms in older men (Ford et al., 2008), the vitamin supplements were found to be no more effective than placebo.

Integrative care

Integrative Care In The United States

Research

Consumers and integrative care

Integrative nursing care

Credentials in integrative care

Natural products

Diet and nutrition

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Integrative care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access