Introduction

The Midwives’ Rules and Standards (NMC 2012) clearly highlight’s a midwife’s responsibility within her sphere of practice. Some of the responsibilities and activities from this document are directly related to the recognition of neonatal normality and abnormality as well as the need to refer to the paediatric team and take appropriate emergency action. The midwife’s role in aiding the mother to care for her baby, observe and record normal progress and offer information on health issues that may directly or indirectly affect the health of both her and her baby are reflected within the Standards for Pre-Registration Midwifery Education (NMC 2009a). The midwife’s responsibilities are also referred to in the guidelines Routine Postnatal Care of Women and their Babies issued by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2006).

This chapter also provides a foundation for those students who are undertaking their midwifery education within universities that have integrated the ‘Physical Examination of the Healthy Newborn’ course within their pre-registration midwifery programmes of study.

Midwife’s immediate role

The birth of a baby is a significant event in the life of its parents. For many mothers, the minutes after birth are full of many emotions, including concern about the baby’s condition. At birth, the midwife’s immediate concern is usually related to the baby’s ability to accomplish the initial changes that are required in order to adapt and survive outside the uterus, such as the physiological changes in heart function. A midwife’s ability and attitude at this time are extremely important in providing the parents with adequate and understandable information.

Conversely, the baby’s condition may provoke anxiety at birth or there may be an obvious physical abnormality. Occasionally, an abnormality that was not detected antenatally may present at or soon after birth. For example, the baby may exhibit signs of a chromosomal abnormality, heart conditions or limb abnormality.

The midwife’s sensitivity and level of professional experience and the actions that she takes will enable the parents to ‘cope’ as the initial impact of the issue of concern sinks in. However, it is paramount that the midwife voices her concerns to the parents followed by an explanation regarding the action that she is going to take.

The immediate care and handling of the baby should provide the parents with a professional and appropriate role model at all times; for example, limbs are not handles with which to turn a baby over. However, unswaddling a baby and removing hats when the baby demonstrates good temperature control encourage good role modelling, particularly in relation to the prevention of sudden infant death syndrome. Information and rationales given should be informative and appropriate to the individuals concerned.

The midwife is responsible for the assessment and recording of the initial vital signs of the baby (see sections below entitled ‘Assessment at birth’, ‘Thermoregulation’ and ‘The chest’), thus providing a comprehensive record of the baby’s condition at birth and during the first few hours of life.

The initial introduction of the baby to its parents and when the midwife assists the mother with the baby’s first feed are important landmarks. Both these events link with the need to observe the initial parent–baby attachment process. Factors arising before and during pregnancy can affect these processes – for example, maternal abuse, domestic violence, environmental and social concerns (for example, housing and sanitation) or the circumstances under which the pregnancy was conceived. If this initial attachment process is affected, good communication both verbally and in written format with members of the midwifery team and other healthcare providers is paramount, as it enables all professionals involved to be well informed of the situation and assists effective multidisciplinary communication.

Comprehensive record keeping is a necessity if the midwife is to demonstrate that she has acted in accordance with her professional responsibility, local guidelines/procedures and parental wishes (NMC 2009b). The woman’s record should provide information regarding an agreed plan of care, midwifery/obstetric and paediatric involvement including actions taken and why, any changes required and the rationale for so doing, maternal consent when required, observations performed and any other information as it arises. Information on both the antenatal and intrapartum periods may relate to the condition of the baby at or soon after birth. Reading previous notes made by other staff and providing comprehensive notes at the time of giving care are not a luxury, they are a professional necessity.

Initial assessment and examination at birth

Assessment at birth

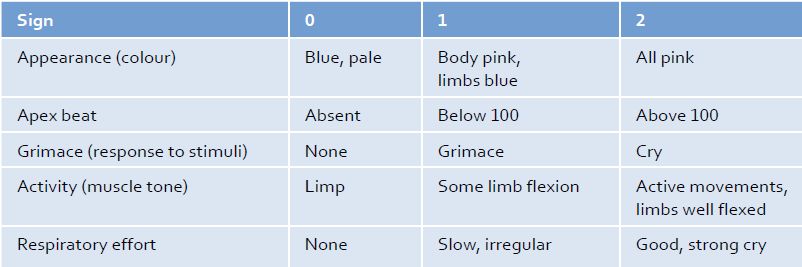

Assessing the condition of the baby at birth is in the first instance by means of the Apgar scoring system (Table 9.1) and secondly by performing a complete physical examination in order to confirm normality and detect any anomalies.

Dr Virginia Apgar devised the Apgar scoring system in the 1950s (AAP/ACOG 2006). It consists of a systematic assessment of five key factors, each significant in determining the health status of the baby. Each factor is given a score (from 0–2), so the overall condition of the baby can be determined by calculating the score out of a total of 10. The Apgar score is usually calculated at 1 min and again at 10 min after birth. A score of 0–3 at 1 min indicates a baby who is in poor condition, requires resuscitation and possibly ventilation, whereas a score of 7–10 at 1 min usually indicates a baby who is in good condition and is able to make the adaptations necessary for extrauterine life. A good account of the Apgar scoring system is contained in Johnson & Taylor (2010).

Examination of the newborn baby

In the UK, each baby within 72 hours of birth is given a comprehensive physiological neonatal examination the standard for which is set by the Newborn and Infant Physical Examination committee (National Screening Committee 2008) by a midwife who holds an additional qualification in the physical examination of the newborn, a paediatrician, general practitioner or specially trained neonatal nurse specialist. This examination involves a more in-depth assessment of neonatal well-being and also incorporates cardiovascular and respiratory assessment, examination of the eyes and testes and assessment of hip stability. However, the initial assessment and examination that is performed by the midwife immediately after birth is paramount in providing information regarding the initial parameters of health and well-being of the baby at birth and highlighting conditions that need urgent management soon after birth or paediatric review postnatally.

Table 9.1 The Apgar scoring system (AAP/ACOG 2006)

Preparation

Under normal circumstances, this initial examination can be performed within the first hour after birth after the parents have had time to look at and cuddle their baby. The process of the examination should be explained to the parents and their consent obtained. The examination should be performed where it can be easily witnessed by the parents and the lighting is good, particularly natural daylight. Hands should be washed and dried prior to the examination and everything required should be close at hand (for example, scales and baby clothes). The examination itself should be performed quickly and comprehensively, only uncovering the part of the baby to be examined and re-covering the baby as soon as practicable.

Before commencing the examination, visually observe the baby, noting:

Address any urgent requirements such as obvious abnormalities or a baby who appears distressed or cyanosed. Continue to observe these five key points during the process of the initial examination in order recognise if the baby’s condition changes.

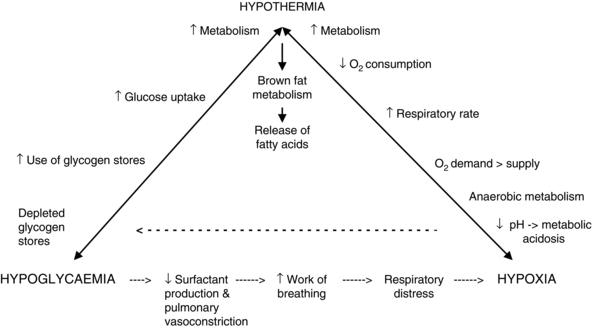

Thermoregulation

A baby emerges from the warm uterine environment (37°C+) to a much lower temperature of approximately 21°C. Loss of body heat can occur quickly, due to the baby’s skin being wet, a large ratio of surface area to body mass and the relatively thin layer of insulating subcutaneous fat. A drop of 1–2°C can occur during the immediate postbirth period and if the baby has suffered some form of compromise – such as hypoxia, the baby is small in relation to the gestational age or if infection is present – this can result in a baby who may be unable or slow to regain a normal body temperature. Hypothermia is one of the three major considerations within the energy triangle (Figure 9.1).

The close relationship of hypothermia, hypoglycaemia and hypoxia/anoxia must never be underestimated. The midwife needs to be vigilant in facilitating the baby’s adaptation to extrauterine life by being aware of the interactions between these three major factors and her role in recognising external factors that may have an adverse impact.

The risk of the baby becoming hypothermic (low body temperature) will increase if the baby has not been dried adequately, is preterm or is less than the expected weight for its gestational age. This is because small and/or preterm babies have less brown fat to utilise for energy/heat production. Brown fat (otherwise known as brown adipose tissue) is present in the body of newborn babies and is used to generate body heat. In terms of the baby’s body temperature, one must be aware that the presence of infection may cause the baby’s temperature to rise as well as fall.

As has been discussed, it is important to prevent hypothermia so the room and cot in which the baby is to be examined need to be warm (turn fans off) with no draughts (close windows/doors). It is also good practice to assess the temperature of the baby before commencing the examination and maintain awareness of its temperature during the examination. In some sites, checking the temperature of the baby may not be routine but assessing the warmth of the baby’s chest and upper back with the back of the hand during the examination is good practice. It must also be borne in mind that when using thermometers to measure temperature, their accuracy depends on the site and technique used (Johnson & Taylor 2010).

Head

Observe the overall shape and symmetry of the skull, bearing in mind that these factors may be influenced by the presence of moulding or caput succedaneum as described below.

The suture lines on the skull should be easily palpable and may be found to be overlapping due to the pressures exerted during labour – a process known as ‘moulding’. The parents should be reassured and made aware that this will resolve over the next 24–48 hours.

The oedematous area on the fetal scalp in the vicinity of the presenting part of the head is known as caput succedaneum. The oedema can cross suture lines and is more obvious after prolonged labour but will normally only remain evident for a short while, usually disappearing within 48 hours.

Sometimes there is a soft, bruised-looking swelling that is restricted by the bone margins over which it is localised (usually the parietal bones), known as a cephalhaematoma. It is due to a localised subperiosteal haemorrhage, often occurring as the result of no apparent trauma except for the usual pressure that occurs on the presenting part of the fetal head. Parents will need to be reassured that the cephalhaematoma will gradually reabsorb, usually over a period of 3 months. If bilateral cephalhaematomas are present, they may take longer to disappear. In an extremely small proportion of cases, a fracture may be suspected and if present will be seen on an X-ray of the skull.

The cranial fontanelles should be observed for normality. The posterior fontanelle located at the junction of the lambdoid and sagittal sutures is usually triangular and measures approximately 0.5 cm at birth, closing shortly afterwards. The anterior fontanelle measures approximately 3–4 cm at the largest diameter and usually closes between 18 months and 2 years of age.

A large anterior fontanelle may be found in the premature baby or be due to hydrocephalus, while a small one may indicate microcephaly. If the fontanelle appears raised or tense, this may be associated with hydrocephalus or indicate raised intracranial pressure or infection. However, a depressed fontanelle may suggest that the baby is dehydrated but this is very rarely seen at birth and tends to be a ‘late’ sign of dehydration. Occasionally, there is a third fontanelle to be found between the anterior and posterior fontanelles, the size of which can be variable. It can be indicative of congenital abnormalities (e.g. trisomy 21).

The whole head needs to be examined for the presence of trauma (for example, forceps marks, fetal scalp electrode or amnihook lacerations) or bruising (for example, Kiwi or ventouse cup). In the event of any bruising, the parents should be made aware that the baby is more likely to demonstrate physiological jaundice, due to the increased breakdown of red blood cells.

The occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) is noted and provides a record, for example, in the event of hydrocephalus occurring. Place the centimetre scale of a tape measure 1 cm above the nasal bridge and encircle the largest diameter and note the measurement in the neonatal record. The measurement tends to be more accurate if the baby’s head is lifted off the mattress (caput can distort the measurement) or the measurement can be taken when the baby is being held. The degree of moulding can of course affect the measurement noted.