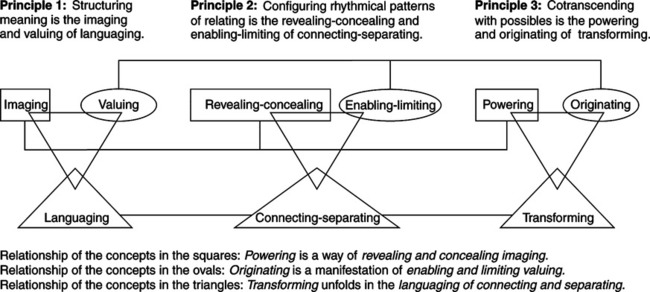

Gail J. Mitchell and Debra A. Bournes Rosemarie Rizzo Parse, a member of the American Academy of Nursing, is Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Loyola University Chicago. She is founder and editor of Nursing Science Quarterly, and president of Discovery International, which sponsors international nursing theory conferences. Dr. Parse is also founder of the Institute of Humanbecoming, where she teaches the ontological, epistemological, and methodological aspects of the humanbecoming school of thought (Parse, 1981, 1992, 1996, 1998, 2007b). She consults throughout the world with doctoral programs in nursing and with healthcare settings that are utilizing her theory as a guide to research, practice, education, and regulation of standards for quality in practice and education. Dr. Parse is the author of many articles and books, including Nursing Fundamentals (1974), Man-Living-Health: A Theory of Nursing (1981), Nursing Science: Major Paradigms, Theories and Critiques (1987), Nursing Research: Qualitative Methods (1985) (co-authored), Illuminations: The Human Becoming Theory in Practice and Research (1995), The Human Becoming School of Thought: A Perspective for Nurses and other Health Professionals (1998), Hope: An International Human Becoming Perspective (1999), Qualitative Inquiry: The Path of Sciencing (2001b), and Community: A Human Becoming Perspective (2003a). The Human Becoming School of Thought (1998) was selected for Sigma Theta Tau and Doody Publishing’s “Best Picks” list in the nursing theory book category in 1998. Hope: An International Human Becoming Perspective was selected for the same list in 1999. Many of her works have been translated into Danish, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Spanish, Swedish, Taiwanese, Korean, and other languages. Parse’s multiple research projects and interests are focused on lived experiences of health and human becoming. She has developed basic and applied science research methodologies (Parse, 2005) congruent with the ontology of humanbecoming and has conducted and published numerous investigations on a wide variety of phenomena, including laughter, health, aging, quality of life, joy-sorrow, contentment, feeling very tired, respect, and hope. She was principal investigator for the Hope study, which included participants and coinvestigators from nine countries (Parse, 1999). Following that, Parse (2007a) further elaborated understanding of the concept of hope in her humanbecoming hermeneutic study of hope in King’s (1982) “Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption.” Parse’s research methodologies have been used by nurse scholars in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and other countries (Doucet & Bournes, 2007). Her theory guides practice in various healthcare settings in Canada, Finland, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and others. Humanbecoming is also used as a guide for education, administration, leadership, change, mentoring, and regulation in several settings on five continents. The humanbecoming school of thought is grounded in human science proposed by Dilthey and others over the past century (Cody & Mitchell, 2002; Mitchell & Cody, 1992; Parse, 1981, 1987, 1998, 2007b). The humanbecoming school of thought is “consistent with Martha E. Rogers’ principles and postulates about unitary human beings, and it is consistent with major tenets and concepts from existential-phenomenological thought, but it is a new product, a different conceptual system” (Parse, 1998, p. 4). At the time she was developing her theory, Parse was working at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. While she was there (during the 1960s and 1970s), Duquesne was regarded as the center of the existential-phenomenological movement in the United States. Dialogues she had with scholars in this school of thought, such as van Kaam and Giorgi, stimulated and focused her thinking on the lived experiences of human beings and their situated freedom and participation in life. By synthesizing the science of unitary human beings, developed by Martha E. Rogers (1970, 1992), with the fundamental tenets from existentialphenomenological thought, as articulated by Heidegger, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty, Parse secured nursing as a human science. She contends that humans cannot be reduced to component systems or parts and still be understood. Persons are living beings who are more than and different from any schemata that divide them. Parse challenges the traditional medical view of nursing and distinguishes the discipline of nursing as a unique, basic science focused on human lived experience. Parse supports the notion that nurses require a unique knowledge base that informs their practice and research, and this knowledge (of the humanuniverse process) is essential for nurses to fulfill their commitment to humankind (Parse, 1981, 1987, 1993, 2007b). In developing her theory, Parse was especially influenced by Rogers’ principles of helicy, integrality, and resonancy and by her postulates (energy field, openness, pattern, and pandimensionality) (Parse, 1981; Rogers, 1970, 1992). These ideas underpin Parse’s notions about persons as open beings who relate with the universe illimitably, that is, “with indivisible, unbounded knowing extended to infinity” (Parse, 2007b, p. 308), and who are indivisible, unpredictable, everchanging, and recognized by patterns (Parse, 1981, 1998, 2007b). From existential-phenomenological thought, Parse drew on the tenets of intentionality and human subjectivity and the corresponding concepts of coconstitution, coexistence, and situated freedom (Parse, 1981, 1998). Parse uses the prefix co on many of her words to denote the participative nature of persons. Co means together with, and for Parse, humans can never be separated from their relationships with the universe. Relationships with the universe include all the linkages humans have with other people and with ideas, projects, predecessors, history, and culture (Parse, 1981, 1998). From Parse’s perspective, humans are intentional beings. By this she means that human beings have an open and meaningful stance with the universe and the people, projects, and ideas that constitute lived experience. Human beings are intentional in that their involvements are not random but are chosen for reasons known and not known. Parse says that being human is being intentional and present, open, and knowing with the world. Intentionality is also about purpose and how persons choose direction and ways of thinking and acting toward projects and people. People choose attitudes and next actions from a realm of possibilities (Parse, 1981, Parse, 1998). The basic tenet, human subjectivity, means viewing human beings not as things or objects but as beings that are indivisible, unpredictable, and everchanging (Parse, 1998), and as beings that are a mystery of being with nonbeing. Human beings live what was, is, and will be in the now moments of their intersubjective relationships with the universe. Parse posits that the human’s presence in and relationship with the world are personal, and humans assign meaning to their lives and to their projects in the process of becoming who they are. As people choose meanings and projects, according to their value priorities, they coparticipate with the world in indivisible, unbounded ways (Parse, 1981, 1998, 2007b). Every person, although inseparable from the world and from others, crafts a unique relationship with the universe. Human beings have a personal relationship with the universe that is open to new possibilities and directions. The personal relationship is the person’s becoming, and becoming is complex and full of explicit-implicit meanings (Parse, 1981, 1998). Coconstitution is the idea that the meaning of any moment or situation is linked with the particulars that contribute to the moment or situation (Parse, 1981, 1998). Human beings choose meaning as they choose to see and evaluate the particular constituents of day-to-day life. Life happens, events unfold in expected and unexpected ways, and the human being coconstitutes personal meaning and significance. Coconstitution surfaces with opportunities and limitations for human beings as they live their presence with the world, and as they make choices about what things mean and how to proceed. The term coconstitution also links to the ways people create different meanings from the same situations. People change and are changed through their personal interpretations of life situations. Various ways of thinking and acting unite familiar patterns with newly emerging ones as people proceed with crafting their unique realities. The term coexistence means “the human is not alone in any dimension of becoming” (Parse, 1998, p. 17). Human beings are always with the world of things, ideas, language, unfolding events, and cherished traditions, and they also are always with others—not only contemporaries, but also predecessors and successors. There is no individual in Parse’s humanbecoming theory. There is only community that one has been cocreated with (Parse, 2003a). There is the personal and there is the intersubjective, and even the way one knows self as a human being is linked intimately to the ways others think and act around persons. Indeed, Parse posits that “without others, one would not know that one is a being” (Parse, 1998, p. 17). Persons think about themselves in relation to how they are with others and how they might be with their plans and dreams. Coexistence links with the notion of mutual process and the unity of lived experience. No objective-subjective dualities or cause-effect relationships can represent humanbecoming. Linked to the assumption of freedom, Parse describes an abiding respect for human change and possibility. Finally, situated freedom means that human beings emerge in the context of a time and history, a culture and language, physicality, and potentiality. Parse suggests that human freedom means “reflectively and prereflectively one participates in choosing the situations in which one finds oneself as well as one’s attitude toward the situations” (Parse, 1998, p. 17). Humans are always choosing. Persons decide what is important in their lives. They decide how to approach situations and what projects and people to pay attention to. Day-to-day living represents people choosing and acting on their value priorities, and value priorities shift as life unfolds. Sometimes being able to act on beliefs is as important as achieving the desired outcome. Personal integrity is linked intimately to the notion of situated freedom. In 2007, Parse published important conceptual refinements for the humanbecoming school of thought. First, she changed human becoming and human-universe to humanbecoming and humanuniverse. These changes, according to Parse (2007b), further specify her commitment to the indivisibility of cocreation. Parse’s new concepts of humanbecoming and humanuniverse demonstrate through language that there is no space for thinking that humans can be separated from becoming or the universe—these notions are irreducible. In addition to her new conceptualizations of humanbecoming and humanuniverse, Parse (2007b) specified four postulates that permeate all principles of humanbecoming. The four postulates are illimitability, paradox, freedom, and mystery. The four postulates further specify ideas already embedded within Parse’s school of thought. Illimitability better represents Parse’s thinking about the indivisible, unpredictable, everchanging nature of humanbecoming. Parse (2007b) stated, “Illimitability is the ‘unbounded knowing extended to infinity, the all-at-once remembering and prospecting with the moment’” (p. 308). Indivisible, unbounded knowing “is a privileged knowing accessible only to the individual living the life” (Parse, 2008b, p. 46). Paradox has always been affiliated with humanbecoming, and Parse’s bringing it forth as a postulate that permeates all theoretical principles emphasizes the importance of paradox in human cocreation. She stated, “paradoxes are not opposites to be reconciled or dilemmas to be overcome but, rather, are lived rhythms…expressed as a pattern preference” (p. 309), “incarnating an individual’s choices in day-to-day living” (Parse, 2008b, p. 46). Humans make choices about how they will be with paradoxical experiences and continuously make choices about where to focus their attention. For example, all humans live paradoxical rhythms of certainty-uncertainty, joy-sorrow, and others, and they move with the rhythm of their paradoxical experiences—at times focusing on certainty or joy, for instance, yet always having an awareness of living the uncertainty or sorrow inherent in situations. Likewise, freedom, although a cornerstone of Parse’s early thinking, is positioned in a new light in her most recent thinking. Here, she (Parse, 2007b) stated that freedom is “contextually construed liberation” (p. 309). People have freedom with their situations to choose ways of being. Finally, mystery, the fourth postulate, is presented in a more specific way as something special that transcends the conceivable and as the unfathomable and unknowable that always accompanies the “indivisible, unpredictable, everchanging humanuniverse” (p. 309). Based on her latest thinking, Parse (2007b) also refined the wording of the three principles of her theory as indicated in the following. Research guided by the humanbecoming theory is meant to enhance understanding of the theoretical foundation, or the knowledge contained in the principles and concepts of the humanbecoming theory. Research is not used to test Parse’s theory. Nurses do not set out to test if people have unique meanings of life situations; or if persons have situated freedom; or if humans are indivisible, unpredictable, everchanging beings; or if persons relate with others and the universe in paradoxical patterns. To test these beliefs would be comparable to testing the assumption that humans are spiritual beings or that people are composed of complex systems. These statements are abstract beliefs based on experience, observation, and beliefs about the nature of reality. The foundational or ontological statements are value laden, and, as noted earlier, a nurse either has an attraction and commitment to these foundational beliefs or not. The idea of a human being who is indivisible, unpredictable, everchanging and freely choosing meaning is an assumption that is either believable or not. Assumptions about human beings are theoretical, not factual. A student or a nurse relates to one notion of human being or another. According to Parse, this is why there is a need for multiple views; the discipline of nursing can and does accommodate different views and different theories about the phenomenon of concern to nursing—the human-universe-health process. In agreement with Hall, Parse (1993) stated the following when discussing the issue of testing the humanbecoming theory: The human becoming theory does not lend itself to testing, since it is not a predictive theory and is not based on a cause-effect view of the humanuniverse process. The purpose of the research is not to verify the theory or test it but, rather, the focus is on uncovering the essences of lived phenomena to gain further understanding of universal human experiences. This understanding evolves from connecting the descriptions given by people to the theory, thus making more explicit the essences of being human (p. 12). Research with Parse’s theory expands understanding about humanly lived experiences and builds new knowledge about humanbecoming. Knowledge of humanbecoming contributes to the substantive knowledge of the nursing discipline. Disciplinary knowledge is different from the practical or technical knowledge that nurses use in various healthcare settings. Disciplinary knowledge is theoretical and identifies the phenomenon of concern for nurses—for Parse (1998, 2007b), humanbecoming. According to Parse (1998), “Scholarly research is formal inquiry leading to the discovery of new knowledge with the enhancement of theory” (p. 59). This idea of new knowledge with enhancement of theory requires additional attention to clarify the distinctions among different ways of thinking. Research guided by the humanbecoming theory explores universal lived experiences with people as they live them in day-to-day life. Parse contends that there are universal human experiences, such as hope, joy, sorrow, grief, anticipation, fear, confidence, and contemplation. Further, persons experience what was, what is, and what will be—all at once. This means that research guided by the humanbecoming theory explores lived experiences as people live them. People live in the moment, and what is remembered and what is hoped for are always viewed within the reality of the now. Further, universal experiences cannot be reduced to linear time frames because lived experiences are cocreated with “indivisible, unbounded knowing” (Parse, 2007b, p. 308). A nurse researcher conducting a Parse method study invites persons to speak about a particular universal experience. For instance, a researcher might invite a participant to talk about his or her experience of grieving (Cody, 1995a, 2000; Pilkington, 1993). The researcher would not ask the participant to speak about grieving while in the hospital, for example, because lived experiences are not compartmentalized. The researcher guided by humanbecoming knows that the person’s reality encompasses what is remembered and what is imagined or hoped for as it is appearing in the moment (Parse, 2007b). The researcher also assumes that the person knows his or her experience and can offer an account of the experience as he or she lives and knows it. What is shared about the experience under study is what Parse (2008b) called “truth for the moment” (p. 46). Truth for the moment is the person’s description of his or her reality, an expression of “personal wisdom” (Parse, 2008b, p. 46) about the phenomenon under study in light of what is happening and known in that instant. Truth, from this perspective, is “unfolding evidence, testimony to everchanging knowing, as new insights shift meaning and truth for the moment” (Parse, 2008b, p. 46). Thus, all research evidence is “truth for the moment.” In 1987, Parse first developed a specific research method consistent with the humanbecoming theory; since then, her humanbecoming hermeneutic method has been articulated (Cody, 1995c; Parse, 1998, 2001b, 2005, 2007a). A third method, an applied science method (qualitative descriptive preproject-process-postproject) has also been articulated (Parse, 1998, 2001b). For details of all these methods, please see The Human Becoming School of Thought: A Perspective for Nurses and Other Health Professionals (Parse, 1998) and Qualitative Inquiry: The Path of Sciencing (Parse, 2001b). The Parse research method records accounts of personal experiences and systematically examines those accounts to identify the aspects of lived experiences that are shared across participants. The core concepts, or ideas shared across all participants, form a structure of the phenomenon under study. The structure as defined by Parse (2007c) is the “paradoxical living the now of remembering and prospecting allat-once.” New knowledge is embedded in the core concepts, and, once discovered, the new knowledge enhances theory and understanding in ways that go beyond the particular study. The weaving of the new knowledge with the theoretical concepts expands understanding of the content of the humanbecoming theory, and that is how the new knowledge develops disciplinary and interdisciplinary thinking and dialogue. Parse (1998) synthesized “principles, tenets, and concepts from Rogers, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Sartre…in the creation of the assumptions about the human and becoming, underpinning a view of nursing grounded in the human sciences. Each assumption is unique and represents a synthesis of three of the postulates and concepts drawn from Rogers’ work and from existential phenomenology” (p. 19). This underscores just how firmly Parse’s theoretical sources underpin her development of the humanbecoming school of thought. Parse draws upon the work of other theorists to build a solid foundation for a new nursing science. Accordingly, the assumptions underpinning the humanbecoming theory focus on beliefs about humans and about their becoming, which is health. Parse does not specify separate assumptions about the universe, because her belief is that the universe is illimitable and cocreated with humans—rather than separate from humans. This is evident in Parse’s (1998, 2007d) assumptions about humans and becoming: Parse (1998, 2007d) synthesized the original nine assumptions about humans and becoming into three assumptions about humanbecoming, as follows: 1. Humanbecoming is freely choosing personal meaning with situation, intersubjectively living value priorities. 2. Humanbecoming is configuring rhythmical patterns of relating with humanuniverse. 3. Humanbecoming is cotranscending illimitably with emerging possibles. Three themes arise from the assumptions of the humanbecoming theory. These include (1) meaning, (2) rhythmicity, and (3) transcendence (Parse, 1998). The postulate’s illimitability, paradox, freedom, and mystery (Parse, 2007b) permeate the three themes. Meaning is borne in the messages that persons give and take with others in speaking, moving, silence, and stillness (Parse, 1998). Meaning indicates the significance of something and is chosen by people. Outsiders cannot decide the meaning or significance of something for another person. Nurses cannot know what it will mean for a family to hear news of an unexpected illness or change in health until they learn the meaning it holds from the family’s perspective. Sometimes people may not know the significance of something until meaning is explored and possibilities examined. Personal meanings are shared with others when people express their views, concerns, hopes, and dreams. According to Parse (1998), meaning is linked with moments of day-to-day living, as well as with the meaning or purpose of life itself. Rhythmicity is about patterns and possibility. Parse (1981) suggests that people live unrepeatable patterns of relating with others, ideas, objects, and situations. Their patterns of relating incarnate their priorities, and these patterns are changing constantly as they integrate new experiences and ideas. For Parse, people are recognized by their unique patterns. People change their patterns when they integrate new priorities, ideas, and dreams, and when they show consistent patterns that continue like threads of familiarity and sameness throughout life. Transcendence is the third major theme of the humanbecoming school of thought. Transcendence is about change and possibility, the infinite possibility that is humanbecoming. “The possibilities arise with…[humanuniverse]…as options from which to choose personal ways of becoming” (Parse, 1998, p. 30). To believe one thing or another, to go in one direction or another, to be persistent or let go, to struggle or acquiesce, to be certain or uncertain, to hope or despair—all these options surface in dayto-day living. Considering and choosing from these options is cotranscending with the possibles. Consistent with her beliefs, Parse does not write about nursing as a concept in the metaparadigm of the discipline. However, she has written extensively about her beliefs concerning nursing as a basic science. Parse (2000) wrote, “It is the hope of many nurses that nursing as a discipline will enjoy the recognition of having a unique knowledge base and the profession will be sufficiently distinct from medicine that people will actually seek nurses for nursing care, not medical diagnoses” (p. 3). For longer than 30 years, Parse has been advancing the belief that nursing is a basic science, and that nurses require theories that are different from other disciplines. Parse believes that nursing is a unique service to humankind. This does not mean that nurses do not benefit from and employ knowledge from other disciplines and fields of study. It means that nurses primarily rely on and value the knowledge of nursing theory in their practice and research activities. Parse (1992) has articulated clearly that she believes “nursing is a science, the practice of which is a performing art” (p. 35). From this view, nursing is a learned discipline, and nursing theories guide practice and research. The belief that nursing is a unique discipline requiring its own theories is often not understood, but discussions around this issue continue to clarify the opportunities nurses have by creating nursing science. Nursing practice for those choosing Parse’s theory is guided by a specific methodology that emerges directly from the humanbecoming ontology. The practice dimensions and processes are illuminating meaning (explicating), synchronizing rhythms (dwelling with), and mobilizing transcendence (moving beyond). For details of practice methodology, see The Humanbecoming School of Thought: A Perspective for Nurses and Other Health Professionals (Parse, 1998). “Nurses who value the humanbecoming belief system live the theory in true presence with others” (Parse, 1993, p. 12). Parse (1993) described practice in the following way: The nurse is in true presence with the individual (or family) as the individual (or family) uncovers the personal meaning of the situation and makes choices to move forward in the now moment with cherished hopes and dreams. The focus is on the meaning of the lived experience for the person (or family) unfolding “there with” the presence of the nurse…The living of the theory in practice is indeed what makes a difference to the people touched by it (p. 12). Nursing, for Parse, is a science, and the performing art of nursing is practiced in relationships with persons (individuals, groups, and communities) in their processes of becoming. Parse (1989) has offered the following set of fundamentals as essential for practicing the art of nursing: Parse (1998, 2007b) views the concepts human, universe, and health as inseparable and irreducible. To emphasize this inseparability, she recently (Parse, 2007b) specified humanuniverse and humanbecoming as one word. For Parse, health is humanbecoming. Health is structuring meaning, configuring rhythmical patterns of relating, and cotranscending with possibles. Parse (1990) speaks of health as a personal commitment, which means, “an individual’s way of becoming is cocreated by that individual, incarnating his or her own value priorities” (p. 136). For Parse (1990), health is a flowing process, a personal creation, and a personal responsibility. Personal health may be changed as commitment is changed, which “include[s] creative imagining, affirming self, and spontaneous glimpsing of the paradoxical” (Parse, 1990, p. 138). Human beings come into the world through others and live their life cocreating patterns of communion-aloneness. This means that persons change and are changed in relating with others, ideas, objects, and events. People become known and understood as they cocreate patterns of relating with people, ideas, culture, history, meanings, and hopes. To understand human life and human beings, an individual must start from the premise that all people are interconnected with predecessors, contemporaries, and even people who are not yet present in the world. Parents may imagine and have a relationship with a child long before the child is conceived and long after a child is lost through death (Pilkington, 1993). Experience has shown that many people at various times have relationships with their parents and other loved ones who are no longer in this world. These are examples of the indivisibility and complexity of humanuniverse and humanbecoming. Parse’s (1981, 1998) principles are the assertions of the humanbecoming theory. Each principle interrelates the following nine concepts of humanbecoming: (1) imaging, (2) valuing, (3) languaging, (4) revealing-concealing, (5) enabling-limiting, (6) connecting-separating, (7) powering, (8) originating, and (9) transforming (Figure 24-1). Research projects generate structures that further specify relationships among the theoretical concepts. For example, Wang (1999) studied hope for persons living with leprosy in Taiwan, and she presented the following theoretical structure: The lived experience of hope is imaging the connecting-separating in originating valuing. Theoretical structures can be used to enhance understanding of specific phenomena as readers consider the detailed participant descriptions that are linked to the concepts of humanbecoming theory. For more information about humanbecoming research, refer to the comprehensive overview of studies compiled by Doucet and Bournes (2007). The inductive-deductive process was central to the creation of the humanbecoming theory. The theory originated from Parse’s personal experiences with her readings and in nursing practice. She deductively-inductively crafted major components of humanbecoming from the science of unitary human beings and existential-phenomenological thought. With her intuitive sense, Parse methodically derived the assumptions, concepts, principles, and practice and research methodologies of the humanbecoming school of thought. Figure 24-1 shows how the principles, concepts, and theoretical structures can be linked. The figure shows the most abstract view of humanbecoming—the simplicity and the complexity of the theory are evident. Abstraction and complexity create possibility for growth, scholarship, and sustainability. The following bibliography demonstrates the broad scope of acceptance by the nursing community. A strong and influential group of nurse scholars is advancing humanbecoming in practice, research, and education. The theory has made a difference to nurses and to persons (patients) who experience humanbecoming practice. The theory informs nurses who work with older persons and with children. The theory guides practice for nurses who work with families and with persons in hospital settings, clinics, and community settings. A community-based health action model, for instance, has been developed and is receiving support from the local community and other funding agencies (Crane, Josephson, & Letcher, 1999). The theory of humanbecoming has also helped to generate controversy and scholarly dialogue about nursing as an evolving discipline and a distinct human science. It is interesting to note that the theory of humanbecoming provides a set of beliefs that can be lived by nurses who have opportunities to be with human beings. It is not a question of whether or not the theory works in any particular setting. The theory has been lived by nurses in the operating theater, in parishes, in shelters, in acute care hospitals, and in other long-term and community settings. A more important question for nurses may be, What settings consistently provide opportunities for nurses to have relationships with persons and families? Parse (2004) created a humanbecoming teaching-learning model that is consistent with the assumptions and principles of humanbecoming. The assumptions, essences, and processes of the model have been used in a variety of ways with students in academic settings (Letcher & Yancey, 2004) and practice settings (Bournes & Naef, 2006). Teachers in academic and practice settings have contributed new understanding and new processes of teaching-learning, and Parse’s theory has been used as a model for explicating pros and cons of teleapprenticeship (Norris, 2002). The humanbecoming school of thought also informs nursing courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels in many schools of nursing. In the text, Man-Living-Health: A Theory of Nursing, Parse (1981) presented a sample master’s in nursing curriculum that incorporated the assumptions, principles, concepts, and theoretical structures of humanbecoming theory. She outlined this process-based curriculum in detail, including course descriptions and course sequencing. The curriculum plan was updated in the 1998 text, The Humanbecoming School of Thought: A Perspective for Nurses and Other Health Professionals, in which Parse outlined a program philosophy and goals, a conceptual framework with themes for the curriculum, program indicators, course culture content, and the evaluation process, and provided a sample curriculum plan consistent with humanbecoming. A master’s degree in nursing curriculum consistent with humanbecoming has been developed at Olivet Nazarene University in Kankakee, Illinois (Milton, 2003a). Many schools of nursing offer students some learning of humanbecoming theory. To date, most students who study the humanbecoming theory and who are guided by the theory in their practice and research activities were introduced to Parse’s work at the master’s level. Parse’s ideas and the humanbecoming theory are increasingly being integrated into undergraduate programs, which will help to expand options for students being taught that nursing is an art and a science that supports multiple perspectives. For example, an undergraduate degree curriculum has now been designed and implemented at California Baptist University in Riverside, California (C. Milton, personal communication, March 11, 2008). In addition, undergraduate and graduate students at York University in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, have the opportunity to study humanbecoming. Humanbecoming theory has guided research studies in many different countries about numerous lived experiences, including feeling loved, feeling very tired, having courage, waiting, feeling cared for, grieving, caring for a loved one, persisting while wanting to change, feeling understood, and being listened to, as well as time passing, quality of life, health, lingering presence, hope, and contentment (see Doucet & Bournes, 2007, for examples). The Parse and the humanbecoming hermeneutic method, underpinned by the humanbecoming school of thought, generate new knowledge about universal lived experiences (Cody, 1995b, 1995c; Parse, 2001a, 2005, 2007a). For instance, research findings have helped to enhance understanding about how people experience hope, while imaging new possibilities and how people create moments of respite amid the anguish of grieving a loss. Research findings are woven with the theory so that findings can inform thinking beyond any particular study. For instance, in several of the grieving and loss studies, researchers described a rhythm of engaging and disengaging with the one lost and with others who remind the one grieving about the one lost (Cody, 1995a; Pilkington, 1993). Women who had a miscarriage already had a relationship with their babies, and the anguish of losing the child was so intense that women invented ways to distance themselves from the reality of the lost child. When they were alone, the pain was unbearable, and when they were with others, the anguish was both eased and intensified as consoling expressions mingled with words acknowledging the reality of the lost child (Pilkington, 1993). Women described rhythms of engaging-disengaging with the lost child and close others, pain, and respite. Linking the rhythm to the theoretical concept connecting-separating means that readers can think about and be present with others’ expressions of engaging-disengaging as they surface in discussions about grieving and loss. How do families in palliative care express their engaging and distancing from the one who is moving toward death? How do parents losing adult children engage and disengage with the absent children? Additional research studies about loss and grieving may further enhance understanding about the connecting-separating concept and other concepts of humanbecoming. In 2004, Mitchell developed a framework for critiquing humanbecoming research that is expanding options for critics engaging humanbecoming-guided nursing science, and the Parse (2001b) research method continues to be refined. For example, in the text, Qualitative Inquiry: The Path of Sciencing, Parse introduced a process in which the researcher constructs each participant’s story, including core ideas of the phenomenon under study. Most recently, Parse changed the name of the participant proposition to language-art, and she added a process that requires the researcher to select or create an artistic expression that shows how the researcher was transfigured through the research process (Parse, 2005). The artistic expression enhances understanding of what the researcher learned about the phenomenon under study. For instance, in her recent study on the experience of feeling respected, Parse (2006) reported that the 10 adult participants in her study described feeling respected as “an acknowledgement of personal worth” (p. 54). They described, for example, feeling confident, being trusted, feeling appreciated, and experiencing joy when feeling respected (Parse, 2006). Parse showed that in each case, the participant spoke about feeling respected as a “fortifying assuredness amid potential disregard emerging with the fulfilling delight of prized alliances” (p. 54). Parse’s (2006) artistic expression for this study—that is, her depiction of her own learning about the phenomenon of feeling respected that surfaced through the research process—was the following poem:

Humanbecoming

CREDENTIALS AND BACKGROUND OF THE THEORIST

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

MAJOR ASSUMPTIONS

The human is coexisting while coconstituting rhythmical patterns with universe (coexistence, coconstitution, and pattern).

The human is coexisting while coconstituting rhythmical patterns with universe (coexistence, coconstitution, and pattern).

The human is open, freely choosing meaning with situation, bearing responsibility for decisions (situated freedom, openness, and energy field).

The human is open, freely choosing meaning with situation, bearing responsibility for decisions (situated freedom, openness, and energy field).

The human is continuously coconstituting patterns of relating (energy field, pattern, and coconstitution).

The human is continuously coconstituting patterns of relating (energy field, pattern, and coconstitution).

The human is transcending illimitably with possibles (pandimensionality, openness, and situated freedom).

The human is transcending illimitably with possibles (pandimensionality, openness, and situated freedom).

Becoming is human-living-health (openness, situated freedom, and coconstitution).

Becoming is human-living-health (openness, situated freedom, and coconstitution).

Becoming is rhythmically coconstituting with humanuniverse (coconstitution, pattern, and pandimensionality).

Becoming is rhythmically coconstituting with humanuniverse (coconstitution, pattern, and pandimensionality).

Becoming is the human’s patterns of relating value priorities (situated freedom, pattern, and openness).

Becoming is the human’s patterns of relating value priorities (situated freedom, pattern, and openness).

Becoming is intersubjective transcending with possibles (openness, situated freedom, and coexistence).

Becoming is intersubjective transcending with possibles (openness, situated freedom, and coexistence).

Becoming is the human’s emerging (coexistence, energy field, and pandimensionality) (Parse, 1998, 2007d).

Becoming is the human’s emerging (coexistence, energy field, and pandimensionality) (Parse, 1998, 2007d).

Nursing

Know and use nursing frameworks and theories.

Know and use nursing frameworks and theories.

Value the other as a human presence.

Value the other as a human presence.

Own what you believe and be accountable for your actions.

Own what you believe and be accountable for your actions.

Move on to the new and untested.

Move on to the new and untested.

Recognize the moments of joy in the struggles of living.

Recognize the moments of joy in the struggles of living.

Appreciate mystery and be open to new discoveries.

Appreciate mystery and be open to new discoveries.

Be competent in your chosen area.

Be competent in your chosen area.

Humanuniverse, Humanbecoming, and Health

THEORETICAL ASSERTIONS

LOGICAL FORM

ACCEPTANCE BY THE NURSING COMMUNITY

Practice

Education

Research

The oak tree stands

noble on the hill

even in

cherry blossom time.

Basho (1644–1694/1962) ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Humanbecoming

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access