CHAPTER 10 Human tissue transplantation

History and background of human tissue transplantation and research

Human tissue transplantation has been a growing part of medical and scientific development for many years. In his book The Body as Property, Russell Scott recounts that more than 2000 years ago Indian surgeons were transplanting human skin in the operation of rhinoplasty.1 Blood transfusions have long been commonplace and the 19th century saw the first transplantation of certain body parts, such as teeth and bone. The 20th century and more particularly the last 30 to 40 years have seen enormous developments in the field of human tissue transplantation. The first successful kidney transplant was performed in 1954 and the first successful transplant of a human heart took place in December 1967, in South Africa; but on that first occasion the recipient died 18 days later. However, a heart transplant performed in the United States only 10 months later kept the recipient alive for over 8 years.2 Since that time the list of tissue, regenerative and non-regenerative, and even human and non-human, that has been transplanted with varying degrees of success has grown considerably. Herring has provided a useful list of the different types of organ transplantation currently available or being explored, and this is set out in Box 10.1.

BOX 10.1 Types of organs potentially available for transplantation3

At the time of writing, the use of human tissue for transplantation, research and other purposes in Australia is the subject of considerable controversy, discussion and debate. Much of this debate is beyond the scope of an undergraduate textbook and some aspects of the debate, particularly those relating to the use of human genetic material in research, will only be mentioned briefly, with further references supplied for the interested reader. Some of the controversy relates to the retention and use of human tissue after death and the conduct of post-mortem examinations, another topic not directly related to the regular work of nurses. However, this latter subject has been a matter of such concern among the general public, it will be discussed in some detail as nurses may find themselves required to answer questions by anxious patients and (more probably) relatives. As a matter of careful practice, specific questions about any matter relating to the use of human tissue should be referred to the appropriate treating medical practitioner, but this area of law has developed so rapidly that undergraduate nurses do now need to be aware of it.

Classifications of human tissue

Human tissue is classified in two ways for the legal consideration of its use in transplantation: namely, regenerative and non-regenerative tissue. Regenerative tissue is the tissue that can be replaced in the body by the normal process of growth and repair. Non-regenerative tissue is all other tissue. The list in Table 10.1 is an example of the wide range of regenerative and non-regenerative tissue currently being transplanted in one form or another.

Table 10.1 Classification of tissue for transplant purposes

| REGENERATIVE TISSUE | NON-REGENERATIVE TISSUE |

|---|---|

Development of law in relation to human tissue usage

The need for parliaments to legislate in this area was first recognised in Australia in 1976, when the then Commonwealth Attorney-General, Mr R J Ellicott, referred the whole matter of human tissue transplantation to the Australian Law Reform Commission under wide-ranging terms of reference. The commission produced its report in 1977, entitled Human Tissue Transplants.4 One of the main features of the report was the proposed draft legislation, which was set out in Appendix 4 to the report. It was intended that the draft legislation, presented to the Commonwealth Government in 1977, would be used as a model by all of the Australian states and territories in relation to this subject. The subject of tissue transplantation is an area within which the states and territories have power to legislate and hence the Commonwealth Government could not impose the draft legislation on the states or territories — it could only put it forward as a suggested model. The Commonwealth Government used the draft legislation proposed by the Australian Law Reform Commission as the basis for the Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1978 in the Australian Capital Territory.

Following the lead of the Commonwealth Government in the Australian Capital Territory, all states and territories have now introduced legislation based on the Commonwealth’s proposed draft legislation.5 The legislation deals with such matters as:

the donation of tissue by living persons, particularly with reference to children and the issue of consent (blood donations are dealt with separately);

the donation of tissue by living persons, particularly with reference to children and the issue of consent (blood donations are dealt with separately);Imogen Goold makes the observation that

In Australia, human tissue use is regulated by a piecemeal, sometimes conflicting body of legislation and case law. In general, these laws have been developed to deal with specific uses of tissue, such as the Human Tissue Acts, and hence do not form a body of rules that can be easily extrapolated to the emerging uses of tissue. The acts are limited in scope and deal only with consent to the removal of tissue, not with its subsequent uses. They also only cover the removal of tissue for transplantation, medical and research purposes, which are rapidly becoming only a few of the many uses to which human tissue may now be put.6

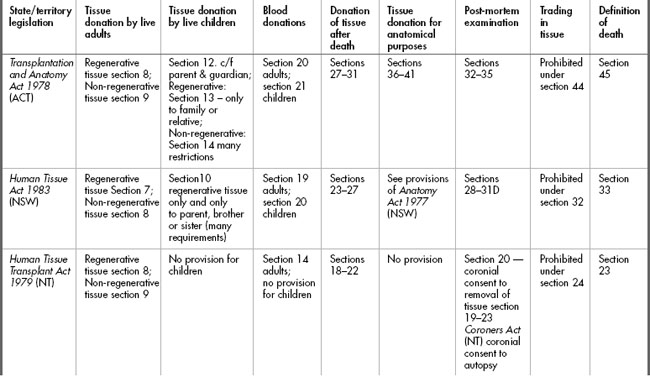

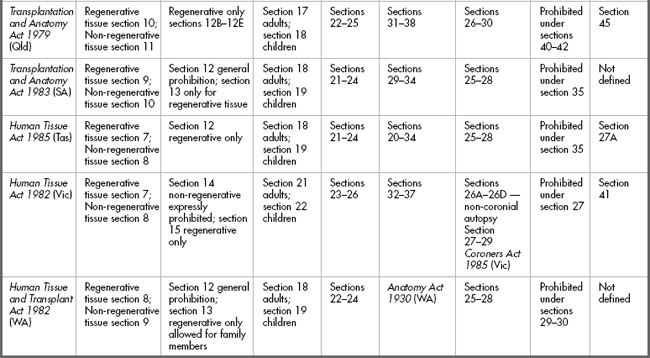

The provisions of the various statutes are set out in Table 10.2. and will be discussed below.

The requirement for consent in live donations

Clearly in situations where tissue is to be donated the requirement for a valid consent is critical. Donating tissue carries with it a degree of risk due to the need to obtain the tissue from a live individual, but this risk becomes even more significant if the tissue removed will not regenerate. The requirements for consent to removal of non-regenerative tissue for donation are quite rigorous, and understandably so, particularly where children are concerned. At the time of writing, The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Australian Health Ethics Committee (AHEC) is developing ethical guidelines on both living and deceased organ donation. A consultation draft document entitled Organ and tissue donation by living donors: Ethical guidelines for health professionals was issued in August 2006. The document points out that, currently in Australia, 40% of kidney donations are from living donors.7

The guidelines themselves embody a set of principles, which are a valuable guide to health professionals in terms of addressing the issues and concerns of living donors, and these are set out in Box 10.2.

BOX 10.2 Principles embodied in AHEC guidelines — Organ and tissue donation by living donors: Ethical guidelines for health professionals8

decision-making processes that ensure that both donors and recipients are fully informed about potential risks, and about alternatives to transplantation; and

decision-making processes that ensure that both donors and recipients are fully informed about potential risks, and about alternatives to transplantation; andAs this document is only at present a consultation document it will be important for nurses who are interested in this topic to visit the NHMRC website (www.nhmrc.gov.au) to view the final version of the document, particularly because often the publication of new versions of such documents may influence states and territories to amend their legislation. However, the principles themselves are sound and it would be unlikely that they would undergo significant change.

Adults

The requirement for consent to removal of regenerative tissue is similar for all statutes but the extent of detail differs. For example, the Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1978 (ACT) section 9 requires that the consent must be in writing; the person giving consent must not be a child (for the purposes of transplantation legislation, a child is a person under 18 years who is not married); and the person must ‘in the light of medical advice furnished to him [sic], understand[s] the nature and effect of the removal’. Furthermore, the consent must be signed ‘otherwise than in the presence of any members of his [sic] family’. These requirements having been met, the person can consent for removal of their regenerative tissue for transplantation or any other therapeutic, medical or scientific purposes. Consent may be revoked orally or in writing at any time. Other statutes such as the Human Tissue Act 1982 (Vic) section 7 do not spell out the requirement for understanding of the nature and effect of the removal, but as has been discussed in Chapter 4, those requirements are part of the common law in relation to consent to treatment. All statutes require the consent to be in writing.

Under all statutes there is a further requirement for a 24 hour ‘cooling-off period’ before the non-regenerative tissue can be donated and a specification that the time of consent shall be recorded. Some statutes also offer the option of a medical practitioner issuing a certificate in relation to consent; for example, section 10 of the Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1978 (ACT).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree