Introduction

This chapter will help you gain the most from all your learning experiences both in the classroom and in placement settings, and will give you practical ideas and guidance that will help you succeed as a student. The focus is on developing the skills that will help you to learn for the rest of your life.

The value of learning for life

The rate of change that we face today is arguably greater than it has ever been in the history of the world (Barnett 2004), and along with the challenge of change also comes the challenge of coping with the vast quantities of information that the modern world is producing. Lukasiewicz (1994) used the phrase ‘ignorance explosion’ to describe this phenomenon and how it affects all of us in society, because no longer can anyone know everything about their subject let alone about several subjects. With large amounts of change and knowledge being generated how can we learn for such an unknown future (Barnett 2004)? This question has been grappled with in recent times, and the discussion has brought a new phrase and concept: ‘lifelong learning’. Lifelong learning refers to the notion that an individual will engage with formal learning throughout their lives; what will be learnt will be determined by the needs of the individual in response to their own survival challenges and of society. To cope with these dramatic changes to our way of living and the volume of informa-tion around us, educational organizations have also been changing their approach to education. They are less concerned about ensuring students can repeat large volumes of facts and figures or transmitting knowledge, but are concerned more with helping students to discover how to learn for themselves. This chapter is about helping you to develop these skills. and so become accomplished at knowing how to learn.

As you have probably already discovered, learning is not only about sitting at a desk or reading a text. In fact, many would argue these are the least effective ways of learning. You will have learned a huge amount of information from using all your senses from watching, listening, tasting, smelling, doing and interacting with others. The trick is to be able to remember what the experience taught you and how you can use the knowledge again and perhaps in a different situation. Sometimes learning like this may happen without even recognizing it has happened (passive learning), such as learning the difference between sweet and sour; sometimes it may be as a result of a decision, for example to ride a bicycle, or to create something (active learning).

Learning nursing

You may have several reasons for continuing or returning to education. Learning to become a nurse is an opportunity for many people to study at university whilst also developing the knowledge and skills for their future career. With the rapid expansion in knowledge the important skills that all workers need to acquire are not concerned with learning facts but knowing how to learn independently so that they can adjust to rapid changes and uncertainty. Expectations of the general public and health care users have become much higher as people have become better informed. If you are to respond safely and effectively to this constant change you will need to learn how to adapt to the changes that new knowledge brings, to be responsive to the demands of your health care clients as well as to the inevitable changes in how health care is delivered as you progress through your career.

Planning to succeed

If you want to succeed then you almost certainly need to do some planning.

Your time is yours to spend as and how you like but recognizing how you use your time is important. There will of course be lots of different things that will be competing for your time; the trick is to decide what is important and what is not and how to allocate your time between these different priorities. Two important points to remember are: your time is yours to control and, if your goal is to become a qualified nurse, then you must dedicate time to that goal.

It is worth stressing that when you start a course in pre-registration nursing your life will change, often in ways that are often impossible to imagine before starting the course. As a result of the changes, the way in which you use your time will need to change also. If you already have a busy life you will need to spend time considering and planning how to make sufficient time and how to adjust your lifestyle to include time for attending university, travelling to your placements and doing your studies. The adjustments you make may affect your friends and family, so it is probably a good idea to share your ideas and plans with them.

Time budgets

You might like to think of time in the same way that you think of money, as a fixed income that needs to be planned and budgeted, so that there is enough for you to achieve all the things that must be achieved, with some to spare for fun and the unexpected. By thinking and planning your time at the beginning of your course you are less likely to run out of time.

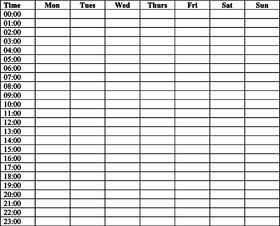

Planning your time will include thinking about how to use all 168 hours of the week. During the course of a week you probably spend about 56 hours sleeping, this leaves you with a balance of 112 hours to spend in a variety of ways. When starting a time budget it is worth examining how you currently spend your time by keeping a record of what you do with your time during one week. Include all the many routine activities that are essential, such as washing and dressing. You might find an activity log like the one shown in Figure 2.1 useful, and using symbols for different activities such as ‘T’ for travel, ‘W’ for work and so on might help.

|

| Figure 2.1Template for a weekly time–activity log. |

To do this exercise effectively you need to keep a record as you go about your daily activities. When you change activities, record how much time you spent on the previous activity. At the end of each day think about how much time you spent on each activity. Is there any time that could be saved? Once you identify how you currently spend your time you can start to plan how you can find time for your course studies. Using this technique lets you see how you are spending time, and so can help you decide where your priorities lie and how you can save time. Knowing how you spend your time will help you to take control of your time, and being in control can help to reduce stress. Take a look at the list that Shona developed and see how it compares with your own (Box 2.1). Making this list helped Shona to recognize how her time was being spent and to fill in her chart.

Box 2.1

Shona’s list

• Sleeping

• Morning and evening wash

• Preparing and eating meals

• Spending time with Gus (partner)

• Collecting children from school

• Sport/exercise

• Travelling: to shops, to work, to school

• Watching TV

• Reading

• Shopping

• Talking to friends

• Washing clothes

• Working

• Playing with children

There are some caveats to time management and these revolve around the fact that how we perceive time and the tasks we have to do varies depending on circumstance. Take a look at some of the sayings connected with time and tasks:

If you want something done ask a busy person.

A job expands to fit the time available to it.

These familiar and apparently contradictory sayings tell us what an unusual phenomenon time is, and how differently people use it, with some people able to achieve a lot more than others within the same amount of time. They also suggest that if we can focus and concentrate on a task it can take less of our time.

Prioritizing your study time

As you get into your studies, you will find that you need to manage your study time. During your studies you are likely to have competing demands for your time, and you will need to review your studies, complete assignments and reflect on practice. We have given you some ideas about how to budget your time; here, we are suggesting that you also need to identify priorities so that you can organize your life and particularly your career studies in an effective and efficient manner.

Tasks you should include:

• Attending classes.

• Reviewing.

• Searching for information.

• Studying.

• Assignments.

• Seminar preparation.

• Presentations.

• Planning/scheduling.

• Meetings with tutor.

• Meetings with mentor.

• Reading.

• Practising clinical skills.

Schedules

One way to manage your study time is to use a series of schedules that relate to different periods of time and priority levels (Rowntree 1998).

Very important tasks

Make a schedule of very important tasks, indicate hand-in dates for all assignments and add other tasks as they occur. Give yourself target dates for all tasks and indicate which are the most important. It is worth remembering that when you write an assignment you are actually learning about your assignment topic, so using your assignment hand-in date as your deadline is not a good target date. You will need more time to reflect and refine what you have written once you have produced your first draft.

From the completion date of these tasks you should then work backwards to important points that lead to the completion of the task. If, for example, you need to produce an essay, an important point could be the completion of the search of the literature or delivering a first draft to your tutor. These events need to be given a completion date in your schedule. When managing a project these important points are often called ‘milestones’. Once all your milestones have been logged and given a completion date you have your ‘main schedule’.

Weekly schedule

The next level of planning is your ‘weekly schedule’. This should be informed by your main schedule but needs to include basic study tasks such as reviewing, practising, searching for information, visits to tutor. You may need to form weekly lists of tasks to inform your schedule, indicating on which day you will complete each task.

When you form your schedule, allocate a certain amount of time to each task. In forming your weekly study schedule you need to pay regard to your overall time budget.

Daily schedule

It is also a good idea to have a ‘daily schedule’. Each night or morning look at your weekly schedule see what you were meant to have achieved and how well you have done. Then schedule your day, prioritize the tasks using EIP (essential, important, postponable). ‘E’ tasks must be done that day. ‘I’ tasks have a high priority but not as high as those graded ‘E’. ‘P’ tasks can be put off. ‘E’ tasks need to have a firm time when they will be tackled, everything stops for an ‘E’. ‘I’ tasks should also have a firm time, ‘P’ tasks can be slotted in when time allows. Cross tasks off your list as you complete them; this will give you a good feeling of satisfaction.

Review your schedules

You must make sure you review your schedules; if you don’t, you may not meet an assignment deadline, or you may fail to revise sufficiently. Your review needs to be done both daily and weekly. On a daily basis look at what you didn’t achieve; if you feel you spent too little or too much time studying a particular subject, adjust the next day’s schedule. Your weekly review needs to do the same, but also needs to be based on an overall view of how long particular tasks take. The time you take to achieve tasks will change as you become more experienced and if tasks that you need to complete become more challenging. When you do a weekly review, you must also bear in mind your overall schedule, in order that you remain on target.

But I hate schedules

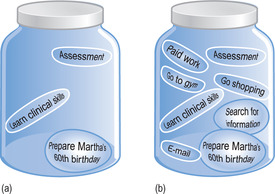

People are different, and some people just hate lists and schedules. Nevertheless, you will have deadlines to meet and you will need to make decisions about your time. An alternative method of thinking about tasks and time is known as the ‘pickle jar theory’ (Figure 2.2). Here, you imagine that all your available time is represented by an empty jar. You first fill your jar with the big important tasks, the ones that are going to make a difference to your life and studies; each task is represented by a pickle, hence big important task, big item of pickle. But if you fill your jar with big pickles you will notice that there is still space; this space can be filled with the less important stuff. Hence, answering the last text message or e-mail will probably come into the small stuff category and should not encroach upon your big pickles. Try Activity 2.1.

|

| Figure 2.2The pickle jar theory. First fill the jar with big, important tasks (a), then add the smaller, less important, stuff (b). (After Wright 2002.) |

Activity 2.1

Produce a schedule for your studies. Decide which targets are the most important, medium important, least important and so on. Next plan when you want to do the work to complete your targets according to their priority. Now develop your schedule for each week, highlighting priority tasks. Don’t forget to reward yourself each time you have completed a target!

Using pictures

Another way of identifying your targets is to draw a picture showing your different goals and their importance to you. You can then use this to help centre your thoughts and focus on particular activities that have most prominence for you. From your picture, produce a weekly schedule, highlighting priority tasks. If you find images help you to remember things better than lists, you may find it helpful to stick or draw a different carton next to each of your targets, so that you associate the image with the target and so remember it better.

Making good use of your study time

Many people starting full-time study courses anticipate that they will have much more time for their studies than they expected. What many people do not realize is that they have to plan their time for this study, otherwise other things use the time up. Having found time for study in your schedule, you need to think about making the most of that time.

Quality of study

Some people can spend longer studying at any one time than others who can concentrate better by taking short breaks after say 20 minutes. By study, we mean focusing on learning something. You will find it helpful to find out for how long you can study before you become restless; is it, for example, 20, 30 or 50 minutes? Knowing what your concentration span is helps you to plan breaks between your periods of study. Breaks should last no longer than your concentration span and are better at about 5 or 10 minutes. When writing this section, for example, I find that I work for about 20 minutes before having a short break. You will probably find that, if you are studying subjects that are unfamiliar or you find difficult, you will only be able to concentrate for a short period. Conversely, if your studying involves activity such as searching for material or practising something, you will probably find that your ability to concentrate is extended. By knowing your concentration span for different study activities you are more able to plan and allocate your time effectively and to know how to use your breaks. You can improve your concentration span by using good note-taking techniques, which we shall be describing further on in this chapter.

Best time to study

When is your best time to study? Are you an early bird or a night owl? When can you fit your study time in around all your home activities? Some people study in the small hours of the night when their family are asleep, others prefer to get up early. Knowing what is your best ‘time’ to study helps you to study effectively.

Minimizing distractions

Regardless of how you study, you need to be focused on what you are studying; this means you need to be free from things that might distract you. What distracts us is very much an individual thing. Some people, for example, do not like studying in quiet rooms as they find silence distracting, whereas others prefer to have music in the background. Also recognizing what has been study and what has been learning through chatting with friends is important. Studying with friends can be very beneficial once the ground work of becoming familiar with the subject has been achieved. Sharing your understanding and testing out your use of unfamiliar terminology or ideas with a small group of trusted friends is very helpful and students who can work this way tend to be more successful.

Adjusting to new learning

Learning new words and learning about unfamiliar ideas can be challenging to newcomers to a course. The process many adults embarking on an unfamiliar subject area go through has been described by Taylor (1986) as a series of experiences that can be both uncomfortable but also exciting, suggesting that adult students initially feel overwhelmed and then angry with themselves and their course teachers. She called this phase ‘disconfirmation’ and it is associated with the struggle to learn the unfamiliar concepts and language of the subject. After this stage, once students had learnt the basic concepts and felt sufficiently confident to talk about the subject with other people, they could move on to the stage of ‘exploration’. This is the stage in a learning process when adult students can acknowledge their struggles, share the experience with others and relate their difficulties to the course material. It also leads to the next stage when students begin to expand their knowledge and are able to relate it to their everyday experiences. This stage Taylor called ‘reorientation’. We have described these stages because being aware that at times you will feel uncomfortable and struggle to learn will help you not to feel quite so isolated. If you don’t quite grasp an aspect of any particular topic, there are some activities you could try (see Activity 2.2).

Activity 2.2

• Ask a friend or colleague if they have understood the topic. If they did, it is likely they will help you and this will improve their understanding even further. If they didn’t understand, then you can work together to help each other. Either way you will feel supported.

• Read some of the articles that are in your course reference list and work through the SQR3 technique (we describe this further on in the chapter).

• Make an appointment to see your tutor to get additional help, making sure that you tell them beforehand what you want to discuss.

In this section we introduce some ideas that will help you to study effectively and how to make notes that you can use both to help you learn and to use when you come to revising for assignments or examinations.

SQ3R

SQ3R is a system that was developed to promote detailed active reading, but it can also be seen as a system for studying. SQ3R stands for ‘survey, question, read, recall, review’ (Beard 1990). Although strictly the acronym should be SQRRR, it is usually written as SQ3R. The focus of the next sections will be the differences between each of the stages. The system will help you to make good use of your study time as it supports reading for understanding or taking a deep approach to your learning.

Survey

The survey stage is the part of the SQ3R process that can take a lot of time as it involves asking not only the question ‘What is this article/book about?’ but also ‘How is it structured?’ and ‘Which bits might be useful?’

Analysing a book or text

You probably started surveying this book by checking the title and then went to look at the contents page at the front and perhaps the index at the back (Figure 2.3). The contents page lists the chapters of the book and sometimes an outline of the ma-terial covered within each chapter. If you are interested in a particular subject such as intravenous infusion and you find a chapter on non-oral nutrition, it would be reasonable to assume that this information would be found in that chapter. If you cannot find the information in the contents page, then try the index. The index records the occurrence of topics in alphabetical order and lists the pages on which each topic occurs. Using the index is more efficient than simply flipping through the book hoping you will find your topic under a heading. You may need to be flexible and use your imagination to think of alternative headings for your topic. For example, information about an intravenous infusion could come under headings such as ‘infusion’, ‘therapy’, ‘hydration’, ‘fluid balance’ and so on. Sometimes a textbook will include a glossary which can provide some guidance as to the likely terms that are used in the text; this is often a good source of help. Other sources of information about a book and its usefulness are the introductory page, the foreword and the preface, which normally contain general information about how a book is structured and for whom it is written. Most books will have a bibliographic page before the main body of the text; this tells you information such as when and where it was published, who it was published by and what edition it is. In a field such as nursing, knowing the date of publication is particularly important as information quickly becomes out-of-date. Similarly, place of publication is important because there is considerable variation in practice, and the names of medicines and equipment, from country to country.

|

| Figure 2.3Surveying texts. |

Skim reading

The next stage in the survey process is to skim read the journal article or the section of the book or the text that you need to understand. At this stage you are reading to get a sense of the content and what the text is about. Does it address the information you really need to know? How much time are you likely to need to read and understand the material? Are you already familiar with the key principles? If the text is right for you then you are ready to go to the next stage of SQ3R.

Questioning and preparing for reading

Before surveying for information, it is a good idea to make an association map using the actual phenomena you are interested in. The associations are words or processes, which are linked with the phenomena you are interested in. This process is similar to what is known as brainstorming or free thinking. In brainstorming you simply write down anything that comes into your head that may be connected to the subject that you are interested in. As you brainstorm do not stop to consider the relative merits of your suggestions, just carry on until you run out of ideas. Once you have done this you can then decide which of your ideas, questions and suggestions are linked to your subject; do not throw out your original list as you may want to refer to it once you have completed your reading. Brainstorming is most effective when carried out with other people and is a very good activity for a study group.

Once you have started your survey and begun to think about the significance of your findings to the subject you are interested in you have entered the questioning stage of the SQ3R technique. At this stage in the process you will need to focus on the type of information and what you want it for. Useful questions will be associated with the textbook or article itself and then with the content:

• Is this text of use?

• Is the article/book suitable for me?

• Does it give me the information that I am searching for?

• Is the content factual/opinion based?

• Is it new information or based on the interpretation of other people’s work?

• What does the author think about this subject?

• What new technical terms are used?

• Can I make sense of what is being said?

• Is it written in a particular style?

• What are the key points of this text and do they relate to my quest?

• What questions am I trying to find the answers to?

• What am I trying to understand?

Your questions should be based on your association map from your brainstorm and your survey of the information in the text. Using this technique will help you to choose texts that meet your needs.

Reading

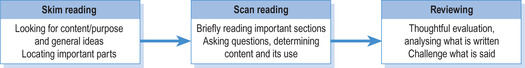

The reading phase at first sight seems obvious, and of course in order to complete the question phase you need to have done some reading. The distinction here is that in the question phase you need to be surveying the text quickly to get an appreciation of the content of the material, whereas in this reading phase you will be reading with much greater depth and focus with the intention of evaluating the material. Figure 2.4 illustrates the steps to take.

|

| Figure 2.4Different forms of reading texts. |

There are thus different forms of reading. In the survey stage of the SQ3R technique you will probably be skimming; in the questioning part, you might be looking in more detail at specific aspects and this might be called ‘scan reading’ (Payne and Whittaker 2000).

Deep reading is a skill that involves concentration. Rowntree (1998) suggests that at this stage taking notes should be avoided. This is because the process of note-taking can distract you from the main task of reading and understanding what is written.

When you read deeply you need to be sceptical and ask questions of what is written. The idea of deep reading is to try to engage and be an active reader. When you are reading at this deep level you are looking to find answers to specific questions. The term deep here is quite important because what you want to avoid is reading at a surface level. If you read at a surface level you will fixate on trying to remember what you read. Remembering is not the main point of reading at a deep level. The main point of reading deeply is to gain understanding because, if you understand why something is done in a certain way, remembering becomes very much easier. To achieve a deep approach to your reading you need to try to relate your reading to something you already know about, your own body functions if you are learning about body functions, or to your everyday experiences if it is concerned with sociology or nursing practice.

When you read, notice whether you can identify individual topics and ideas within the text. These can be generally signified by headings or be more specific and located within individual paragraphs. The survey stage of the SQ3R technique will have helped you to home in on the sections that are relevant to you. You may find it helpful to work with a highlighter pen or a pencil to mark the specific texts you think are important.

Just as each paragraph will normally carry an idea or concept, it may also carry illustrative detail. Following this detail can help you remember the main ideas; trying to remember all the detail will probably be difficult and unnecessary. Often texts provide examples to illustrate a specific point. Do either read through any examples or try to think of your own examples, as they will help you to understand and are often easier to remember.

Reading in a questioning or critical manner comes with practice. When reading in this critical way good starting questions are:

• Do I know this already?

• Is this information something I have never heard of before?

• Is it of use and relevant to the question I am trying to solve?

As you start to evaluate the content, you may ask some basic evaluative questions. These may initially be based on your current experiences and understanding of the subject:

• Does what I am reading match my experience?

• Does this writer’s perspective match those authors of other text(s) I have read?

• Do I agree with the author?

• Are there any contradictions in what is being said?

• Where have the facts come from?

• Are the facts right?

As you read, you may also ask some more analytical questions:

• What are the ideas that support the author’s ideas/argument?

• Do the facts support the conclusion?

• Are the facts true but is the conclusion wrong?

• Do all the examples support the author or are there other examples that do not?

• If some examples do not fit with the author’s view why don’t they fit?

• Is there an alternative conclusion?

• What happens to the idea/argument if some of the supporting facts are not true?

• How do the author’s arguments/ideas fit in with those of other writers?

• Are the arguments good, but do others agree with them?

Finally, some utilitarian questions:

• Is this author’s work worth remembering?

• Should I make notes?

• Should I discuss this work with my tutor, friend or study group?

• How does what the writer suggests relate to my practice: will I change what I do?

Recall

Rowntree (1998) suggests that you are likely to forget about half of the ideas and concepts within what you read the moment you put down what you are reading unless you make an active attempt to recall it. We suggested that the reading aspect of what you do is best conducted without making notes. Making notes is best when undertaking the recall stage of SQ3R. To get the best results from your reading, you need to make use of it and relate it to your existing knowledge of the subject. This means that your note formation should be an active process. Using your reading in your note-making includes providing your own examples and comments on the reading and exploring what other ideas could relate to the information. Other good strategies to help retain the information is to discuss your reading with friends and getting their perspectives, putting what you have read into an assignment or trying to relate the information to your nursing practice experiences.

Recall can occur during the reading stage. For example, you might just pause to think about and make sense of what you have read, putting to one side what you are reading to make some notes. Knowing that you will do some recall will help you concentrate on what you are reading.

Recall takes practice; at first you may want to stop every one or two paragraphs. As you become more familiar with the concepts and language of the text so you become better at describing the content (meaning) to another person. The important aspect of recall is that you should make sense of what you have read without reading the original article. If you cannot recall and make sense of it then you must re-read it. Recall can take time, but it is an essential part of the studying process and has been shown to improve success at college and university.

Your notes should be based on what you initially recall (remember) from your reading. There is no right or wrong way of making notes but they do need to be made in such a way that you can link the notes to the text that you are reading. So making sure you have the full details of the text, (title, author, date, publisher) on each page of your notes and numbering the pages of your notes means you can trace the original text if you need to go back to it.

You could, for example, give a Cornell note page (see below) to each item that you read; each page can then be placed in a file under the particular subject or topic that it relates to. The most important and obvious thing is that you can use your notes at a later stage in your course and so they need to be legible and comprehensible. Some people find that creating a ‘mind map’ or a ‘spider diagram’ is a useful way of documenting the key points of a chapter or article (see below), and use them as a summary with page numbers for each key point. These tools are useful at the initial recall stage of SQ3R as they help you to recognize what you have understood and which sections of the text need further work. Using a mind map or a spider diagram as a record of your reading may require further notes if they are to be of use at a later date.

Review

The final stage of SQ3R is the review stage. This review stage provides an opportunity to go over the notes you have made to make sure they are suitable for the reasons for which you made them. In this stage, check back to the original purpose of your study, go back to the survey stage and ask yourself:

• What did I set out to achieve?

• What was the purpose of this period of study?

• Have I answered my questions from the survey stage?

• Do my notes make sense?

• What did I achieve?”

• What have I learnt from reading this article/book?

• Will I change what I do?

You may want to re-read the article(s) or book chapter, adding to your notes if you find you missed something.

Review your notes as your course progresses, checking that they still represent what you think about the subject and update them as you discover new material and as new research emerges.

Using the SQ3R technique for taught sessions and in practice placements

The SQ3R method is a structured approach to study and as you use it and become familiar with a subject you will find that many of the steps you can do without having to make lists of questions. Don’t try to use the SQ3R approach too prescriptively as you will find that you can adapt the techniques to the type of reading that you are doing. For instance, if you are reading about how to perform a very well-defined and established procedure, you probably will not spend much time evaluating the content but more time questioning your own understanding.

SQ3R in lectures

The SQ3R was originally devised for reading texts, but it can also be used in other circumstances such as lectures and seminars and even when you are learning in practice. In the lecture situation, you will need to do some preparation beforehand. This stage is similar to the survey stage when you think of what questions you would like the lecturer to answer. Using active listening is akin to the reading stage of SQ3R. The recall and review stages are important to carry out at the end of the lecture so that you can begin to relate the content to your own experiences and thus integrate it with your existing knowledge.

SQ3R in practice placement experiences

In practice situations, you can use the SQ3R in several different ways. For example, you can go through each phase of the SQ3R to prepare yourself for your placement while learning about specific skills or patients’ health care needs and for learning about health care delivery.

You can also use the SQ3R technique to prepare for developing a learning agreement or a learning contract for your placement experience. The survey stage is about preparation and finding out what a particular placement experience has to offer. The questioning stage is about focusing on what you want to learn about and the questions that you want answered, perhaps by staff or by patients. The read and recall stages can be used to read up about specific health care problems that patients nursed in the placement are experiencing, and investigations and procedures that they may experience. Using this approach helps you to be knowledgeable and able to learn successfully from your placement.

You can also use the SQ3R technique for preparing to give care or learning about a specific aspect of patients’ health care problems. Your questions may also be related to your own personal development and what you can learn in the setting and how you want to develop. Both the questioning and reading activities can be used when reading patients’ notes and records, or reading through a procedure or text about specific skills and techniques. Your review could be talking to patients to find out about their symptoms or their care and then relating your findings to your reading in your nursing textbook. In addition, you can use the recall stage to make notes about your activities during the shift so that you can review them with your mentor or with your friends, and check them out with your textbooks.

Note-making and note-taking

Note-making is valuable for a variety of reasons and people use note-taking under a variety of circumstances. Here are three principal reasons why you might take notes:

• To help you remember texts or experiences, or advice or instructions.

• To help you learn from texts or taught sessions.

• To create a formal record of interactions, events or conversations.

Styles with which notes are made vary and depend upon personal taste. Essentially there are three types of note-making: linear prose, outline summaries, and diagrammatic (Rowntree 1998). Most students start off using the prose approach but often find that they tend to write too much.

Research has shown that making notes is a very important part of the learning process (Kiewra, 1985 and Kiewra, 1987), especially when the note-making process builds on and extends the learning that has taken place. Note-making is best when it involves using supplementary materials from journals or textbooks that expand what you have learned in a taught session. By making time to reflect upon your taught session and expanding your knowledge, you will find you can remember the information much better. Working this way draws on the same skills that you learned with the SQ3R system.

Another important advantage of making notes is that it helps you to learn how to make accurate notes, which is an essential part of your professional life. You will want to make notes in your practice placements about patients or activities you have been undertaking so that you can create an accurate record. Note-making is thus a skill that is well worth perfecting. People often learn to create their own form of shorthand and to use abbreviations when writing notes. You will need to organize your notes so that you can read and use them easily for your intended purpose, as well as having a good place to store them so you can locate them when needed.

Notes, when used in the context of study, are an interim measure between finding new information and learning it and/or using the information for a specific end. Rowntree (1998) makes the distinction between making and taking notes. Taking notes may be passive when done to aid memory and to concentrate; making notes is usually an active process with a focus on expanding and organizing information and thoughts. There is research evidence to suggest that students who make notes perform better at assessments than those who do not (Annis and Davis 1978, Kulhavy and Dyer 1975).

The Cornell system of making notes

Using the Cornell system (Pauk 1993) can help you to make the most of the material that you are studying. The system provides opportunities for you to follow the SQ3R approach as you write your notes and so helps with your learning. You can use the Cornell system in different settings, such as taught sessions, lectures and seminars, as well as when you are studying texts and in placement settings. The system can also help you to become better at learning through the process of note-taking.

To use the Cornell system you need to divide your notepaper into columns and boxes so you can record specific kinds of information. Have a look at the example that Hannah created when she was studying part of this chapter (Table 2.1).

| 1for reviewing the lecture notes and writing short summaries; helps with organizing your thoughts | |

| 2for recording ideas, explanations and examples using a suitable form of notes | |

| Recall/cue column1 | Recording column2 |

|---|---|

| SQ3R | A system for studying text materials particularly. Need to use five different strategies: survey, question, read, recall, record |

| Survey: skim read 2c if text is Ok 4 me answers 2 in text | Check text for relevance and quality of information; home into specific areas of interest, and so save time |

| Prepare with some questions on subject I want answered (may be tricky if I don’t know anything about the topic) | |

| Read: intensive process | Taylor (1986) says getting to grips with unfamiliar information is difficult and uncomfortable, so I need to be patient with myself and plan enough time to read the first articles, until I feel I have got to grips with the language and ideas |

| Recall: check how much I understand, relate 2 my experiences | After reading article, try to recall the main points; if I can’t go back and read again, will need some memorization as well as application |

| Record: notes of content | Record summary of what I have understood and check against the text for accuracy; must remember to include reference information so I can find the article again if I need to re-read it |

| Plan time | Try out system in class next time and when on placement |

| Reflection and review | Used the process to make notes when reading a text on causes of Down’s syndrome; it was a tough text but the system helped, especially when I came to write up the summary of what I had learned. I found that I could use the new words that I had learned in the class when we discussed the text. This increased my self-confidence |

| Source of notes | Pauk W 1993 How to study in college. Houghton Mifflin, Boston Scott I, Ely C 2007 Learning how to study and learn effectively. In: Spouse J, Cox C, Cook M (eds) Common foundation studies in nursing. Elsevier, Edinburgh |

Hannah’s use of the Cornell system helped her to create a short and succinct summary of her reading of this chapter up until this point. She included the main points about using the SQ3R method in the second column and then she made very brief notes in the first column in her own form of shorthand; this is called reducing the notes. It helped her to transfer the information into her own language, which is a very important step in helping her to take a deep approach to her studies. It is a good idea to do this as soon as you can after reading a text or attending a taught session.

The bottom section of the Cornell system can be used in different ways; here Hannah has reflected on how helpful the system was for reading a difficult and unfamiliar text. In the next section we shall be discussing how you can use the Cornell system for taught sessions, such as lectures and seminars particularly.

Using the Cornell system for taught sessions

You can use the Cornell system to prepare yourself for a taught session and to summarize what you have gained from the session.

Before you go to a lecture it is a good idea to think about its title and likely content. In the second column write some questions that come to mind.

Read (listen)

When you attend the lecture, use the second column for notes taken during the lecture. Focus on the ideas and explanations and the examples that have been used to support them.

Recall

After the lecture, work on reducing your notes. Do this by asking questions; these questions should be based on the content of the lecture. Put these reduced recall notes in the first column. This process should be completed as soon as possible after the lecture. Reducing the notes in this way will help you sort out the meaning within the notes, and to make sense of them. It will force you to revisit the lecture you have just had, and will help you to recall your learning from the lecture at a later date.

Recite and reflection

The next step is to use what you have written in the recall column to go over what was said in the lecture. At this stage, look just at the recall column not the actual notes. This stage is known as the ‘recite’ stage. Getting together with friends and discussing your understanding is an excellent way of learning and remembering important material. If you can arrange to meet up with others after a taught session in, for example, a study group or during break time, it is a good idea for each of you to describe, using your recall column, what you think the lecture was about and what you think you learned. You may be surprised at the differences between your notes and those of your colleagues.

You may find it helpful to make some notes in your first column about your preparation for the taught session and what you could do better next time to prepare.

Reflection or critical analysis

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access