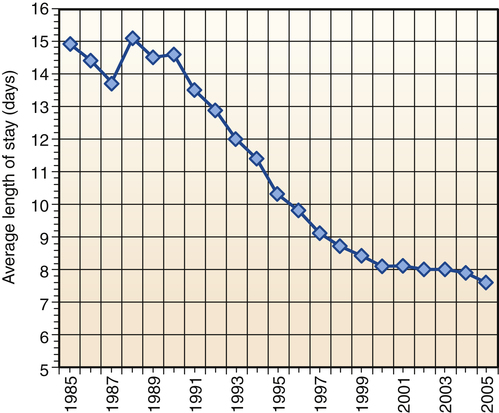

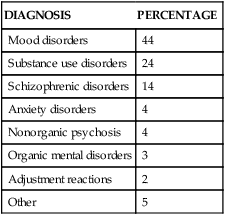

“We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.” Alice didn’t think that proved it at all. 1. Describe recent changes in hospital-based psychiatric care. 2. Examine the components of the therapeutic milieu and its application to hospital-based psychiatric nursing practice. 3. Discuss the caregiving activities of the psychiatric nurse in structured treatment settings. 4. Analyze the psychiatric nurse’s role in integrating and coordinating hospital-based care. The treatment of mentally ill people has always reflected social values and public policy. Contemporary mental health services have been transformed by economic forces, scientific advances, and advocacy movements. Despite national policy that focuses on a shift from hospital to community-based services, critical demand for acute inpatient services continues. Increases in hospital admissions, days of care, and occupancy rates underscore the need for this level of care (National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems, 2011). Inpatient psychiatric units are developed and maintained primarily in response to community need. Although not always profitable, successful programs generate steady patient volumes. Changes in mental health policy and financing have resulted in significant reductions in reimbursement and psychiatric inpatient capacity (Marks et al, 2011). Some of the issues impacting the delivery of inpatient psychiatric services include mental health parity legislation, health care reform, state mental health budget cuts, shortened length of stay, workforce issues, recovery model philosophy, and stigma. Psychiatric nurses are in a unique position to implement strategies to address these challenges and improve the system of care for persons with mental illness. News headlines remind society of the need for psychiatric intervention and the danger of ignoring behaviors associated with mental illness (Pickert and Cloud, 2011). Hospital-based programs play a vital role in the system of care addressing these needs. These trends illustrate some of the unintended consequences of policy and funding decisions. Behavioral health spending must be evaluated broadly to include the need for and access to treatment in addition to dollars spent (Mark et al, 2010; Glick et al, 2011). Indications for inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and treatment objectives are listed in Box 33-1. The focus of psychiatric care has moved away from extended care in inpatient settings toward shorter lengths of inpatient stays with transfer to less intensive settings in the continuum of care. The average length of stay (ALOS) in most psychiatric inpatient settings is 5 to 10 days (Figure 33-1). Specific treatment interventions include detoxification from substances, intervening with support systems, initiation or modification of pharmacological treatment, and follow-up planning. The major psychiatric diagnoses of patients discharged from short-stay hospitals are listed in Table 33-1. In previous years most patients with maladaptive coping responses entered the psychiatric hospital in the acute treatment stage and were able to stay in the hospital until the goal of symptom remission was attained. Currently, most patients are admitted to hospitals in the crisis stage, with the treatment goal of stabilization rather than symptom remission. TABLE 33-1 FIRST-LISTED DIAGNOSIS FOR PATIENTS DISCHARGED FROM SHORT-STAY HOSPITALS From Hall MJ et al: National hospital discharge survey: 2007 summary. Advance data from vital health and statistics, No 29, Hyattsville, Md, 2010, National Center for Health and Statistics. Changes in hospital-based psychiatric care are most evident in the changes that have taken place in state mental hospitals across the United States. The number of state hospital beds has declined by 90% over the past 50 years while the number of people with mental illness has increased (National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems, 2011). The first data collected on state hospitals from 1831 reported 150 patients in four state hospitals. The number steadily rose until 1955, when it peaked at 559,000 patients in 352 state hospitals (Manderscheid et al, 2009). These institutions provided custodial care to patients believed to be unable to safely function in the community or those thought to be a threat to society. Because there are so few beds available, individuals with severe psychiatric disorders who need to be hospitalized are often unable to get admitted. Those who are admitted are often discharged prematurely and without a treatment plan. The consequences of this reduction in psychiatric hospital beds include the following (Treatment Advocacy Center, 2011): • Homelessness: A 2005 federal survey estimated that approximately 500,000 single men and women are homeless in the United States at any given time, and multiple studies have reported that one third have a serious mental illness. • Jails and prisons as psychiatric hospitals: Since the reduction in public psychiatric hospital beds occurred, there has been a significant increase in severely mentally persons in jails and prisons. Estimates have placed the number at 7% to 10% of all inmates, but some studies have put the figure at 20% or higher. • Hospital emergency room overflow: Emergency rooms are often used as waiting rooms for people in need of a psychiatric bed. This backs up the entire hospital system and compromises other medical care. • Violent crime: Studies have shown that between 5% and 10% of seriously mentally ill persons who are not receiving treatment will commit a violent act each year, accounting for 5% of all homicides. The state hospital of the twenty-first century must focus on the needs and characteristics of the specific patient populations it serves, including patients with criminal justice histories, forensic patients, sexually dangerous persons, and the difficult-to-discharge patient with complex ongoing care needs. Research is needed to address the unique treatment and rehabilitative challenges for these populations and to inform future policy decisions (Fisher et al, 2009). Partial hospitalization programs (PHP) are an important part of the continuum of care for mental health and chemical dependency treatment. A PHP is designed to prevent relapse and avoid hospital admission or to provide active treatment for serious mental disorders with reasonable expectation of improvement. PHPs use crisis stabilization and recovery-oriented approaches (Khawaja and Westermeyer, 2010). • Crisis stabilization approaches assist patients to identify personal and environmental triggers, understand the crisis, and develop healthy patterns of problem solving and coping. • Recovery-oriented approaches focus on patient improvements through engagement in their treatment plan, choosing options, and establishing realistic goals in a respectful environment that emphasizes hope and quality of life. PHP patients usually receive 4 to 6 hours of services per day for 4 to 5 days per week (National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems, 2011). Typically, the patient receives the maximum service for the first 1 to 2 weeks after discharge from an inpatient unit. As the crisis stabilizes and the patient’s level of functioning improves, participation in the program is reduced, allowing for transition back to home, work, or school. The PHP team is multidisciplinary and usually includes a psychiatrist, psychiatric nurse, social worker, and activity therapist. Some programs also include occupational therapists and vocational counselors. PHP patients typically are seen by the psychiatrist weekly, and the psychiatric nurse assumes the primary responsibility for assessing and identifying biological issues that may be contributing to the patient’s psychiatric condition. Studies of PHPs have raised questions about their clinical effectiveness and whether they promote the recovery model of psychiatric care (Yanos et al, 2009; Lariviere et al, 2010). In the 1950s, Maxwell Jones described the inpatient environment as a therapeutic community with cultural norms for behaviors, values, and activity (Jones, 1953). He viewed patients’ social interactions with peers and health care workers as treatment opportunities and proposed that clinical staff share community governance with the patient group on an equal basis. He emphasized the benefit of patient’s participation in each other’s treatment, predominantly through sharing information and giving feedback in group settings. In the late 1960s, the idea of the therapeutic milieu emerged (Abroms, 1969). It had two main purposes: Five categories of disturbing behaviors and interventions that can help patients keep maladaptive behaviors under control and allow treatment to progress are listed in Table 33-2. After maladaptive behaviors are limited, the therapeutic milieu can be used to develop the following four important psychosocial skills in mentally ill patients: TABLE 33-2 MANAGING DISTURBING BEHAVIORS IN THE MILIEU 1. Orientation. Orientation is the patient’s knowledge and understanding of time, place, person, and purpose. Awareness of these elements can be reinforced through patient interactions and activities. For example, introducing oneself, one’s role, and the rationale for an interaction helps disoriented patients attend to their surroundings. Other interventions include large unit postings identifying the day, date, and schedule of the day’s activities; patient room white boards identifying important specific information for the patient, including the name of their nurse and physician; community meetings to explain unit structure and answer patient questions in a group setting; and discussions of current events. 2. Assertion. The ability to express oneself appropriately can be role-modeled and exercised in a variety of ways in the treatment setting. Supporting patients in expressing themselves effectively and in a socially acceptable manner on a specific topic or issue is the overall goal. Sample interventions include assertiveness training, anger management groups, and focus groups for lower-functioning patients. 3. Occupation. Patients can feel a sense of confidence and accomplishment through industrious activity. Many therapeutic opportunities are provided through completion of individual or group hands-on activities. Spending time working with patients on something as simple as a jigsaw puzzle can provide purposeful activity, physical skill development, and the added benefit of practiced social interaction. 4. Recreation. The ability to engage in and enjoy leisure time is a beneficial outlet for pleasure and relaxation. Providing a variety of recreational opportunities helps patients apply many of the skills they have learned, including orientation, assertion, social interaction, and physical dexterity. Examples include group and individual games, exercise groups, brief walks outdoors, and participation in a healing garden.

Hospital-Based Psychiatric Nursing Care

Inpatient Psychiatric Care

DIAGNOSIS

PERCENTAGE

Mood disorders

44

Substance use disorders

24

Schizophrenic disorders

14

Anxiety disorders

4

Nonorganic psychosis

4

Organic mental disorders

3

Adjustment reactions

2

Other

5

State Hospitals

Partial Hospitalization Programs

Managing the Milieu

The Therapeutic Community

The Therapeutic Milieu

DISTURBING BEHAVIOR

DEFINITION

INTERVENTIONS

Destructiveness

Physically destructive behavior that is a response to a variety of feelings, such as fear or anger

In working with destructive behavior, the goal is to control or set limits on the maladaptive response but support the feeling underlying the behavior. Validation is essential to help the patient recognize the feeling and ultimately regain control of maladaptive behavior.

Disorganization

Distorted or unusual behavior a psychotic patient may exhibit as symptomatic of the illness may be triggered by elevated anxiety, profound depression, or organic dysfunctions.

Reassure and help the patient while reducing the degree to which these behaviors inhibit therapeutic processes.

Deviancy

Behaviors often described as acting out are the result of the patient expressing conflicts overtly in the environment. It is often difficult to determine precisely what acting-out behavior is or what is justifiable or even tolerable, because much of it may be influenced by sociocultural factors.

The therapeutic goal in working with deviancy is to analyze how the behavior affects the milieu and how it inhibits the patient’s progress. Examining the behavior with the patient and identifying consequences and alternatives are useful approaches.

Dysphoria

Patients with mood alterations may be dysphoric, which is evident in maladaptive responses, such as withdrawal from the environment, obsessional behaviors, intrusiveness, or hyperreligiosity.

Establishing a therapeutic alliance is the first task. From there, the nurse and patient can explore feelings and dysfunctional thoughts and begin to modify behavioral responses.

Dependence

Behavior is evidenced by patients who do not identify and meet their own needs despite being able to do so; the avoidant nature of dependency interferes with therapeutic progress.

The initial therapeutic goal is to work with the patient to draw on any remaining areas of independence and strength. Then situations can be identified in which the patient can apply these independent behaviors successfully.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Hospital-Based Psychiatric Nursing Care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access