1 Jennifer Casavant Telford, PhD, APN-BC and Arlene W. Keeling, PhD, RN, FAAN At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Discuss the impact of Florence Nightingale’s model and the American Civil War on mid to late–19th-century American nursing education. • Describe the transition of nursing education from the hospital to collegiate programs. • Discuss the role of nursing licensure in safeguarding the public and developing educational and clinical nursing standards. • Discuss the development of advanced clinical practice nursing from the 1960s through the present. On September 21, 2001, the Board of Directors of the Association for the History of Nursing adopted a Position Paper wherein the authors make a substantial argument for the integration of the study of the history of nursing throughout all levels of nursing education. In this work, the authors argue that studying nursing history provides nursing students with a “sense of professional identity, a useful methodological research skill, and a context for evaluating information” (Keeling & Ramos, 1995). Therefore the purpose of this chapter is to provide the reader with a brief overview of the history of American nursing from the middle of the 19th century through present-day nursing practice. Because of the breadth and depth of the history of nursing in the United States, this chapter is not meant to be considered exhaustive but instead will focus on selected highlights and major historical events. Topics include Florence Nightingale’s influential nursing practice and the spread of her ideas about nursing education from Britain to the United States; issues surrounding the development of professional and educational standards for nurses; the influence of science and technology on the development of nursing; and the rise of nurse practitioner programs and doctoral education for nurses. Historically, women have been recognized as belonging to the gender charged with providing physical care to those who are sick or injured. Women’s role in society as mothers and caregivers coincided with their domestic duties and was accepted as a natural extension of the homemaker role. To assist mid–19th-century women with their caretaker role, Florence Nightingale published Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not. In the preface of this book, first published in 1859, Nightingale explained that her notes on nursing were “meant simply to give hints for thought to women who have personal charge of the health of others. Every woman … or at least almost every woman has, at one time or another of her life, charge of the personal health of somebody, whether child or invalid—in other words, every woman is a nurse” (Nightingale, 1859, p. 8). Although more than 150 years have passed since Nightingale wrote her book, and today’s nurses are professionals, many of her notes on nursing continue to be relevant to contemporary nursing practice. Florence Nightingale is well known for her work during the Crimean War (1853 to 1856). Her wartime experience shaped her ideas about the value of the trained nurse and was later the impetus for the creation of the Nightingale Training School for Nurses at St. Thomas’s Hospital in London in 1860. Just as Nightingale’s work in the Crimea was an impetus for instituting a training school for nurses in England, the provision of nursing care by American women during the United States Civil War (1861 to 1865) demonstrated the effectiveness of skilled nursing on improving outcomes for sick and injured soldiers. Women from both the North and South volunteered en masse to care for the injured, sick, and dying soldiers in hospitals and infirmaries and on battlefields. Their success in reducing morbidity and mortality in the camps provided evidence that the use of trained nurses could benefit the military and society as a whole. Thus in the years following the war, philanthropic women in the United States devoted their energies to establishing nurse training schools that were based on the Nightingale model (Woolsey, 1950; Dock, 1907). In 1873 fewer than 200 hospitals existed in the entire United States. In a relatively short time, training schools gained in popularity, and by 1900 the United States had 432 such schools (Roberts, 1954). By 1910 there were more than 4000 hospitals in existence (Melosh, 1982). The training in these hospital-based schools was arduous, requiring long days of patient service. Classes were held at the end of the day on the wards. Aside from patient care, students’ duties included housekeeping, meal preparation, and assisting physicians. A 1902 textbook of nursing describes the relationship between physicians and nurses during this era: “To the doctor, the first duty [of the nurse] is that of obedience—absolute fidelity to his orders, even if the necessity of the prescribed measures is not apparent to you. You have no responsibility beyond that of faithfully carrying out the directions received” (Weeks-Shaw, 1902, p. 4). hospitals. In 1893 Isabel Hampton, Superintendent of the Johns Hopkins Hospital School of Nursing, assembled superintendents of America’s largest schools at the World’s Fair in Chicago to discuss nursing education problems. Discussions among these women resulted in a movement to raise and standardize the training of nurses (Billings & Hurd, 1894). In January 1894 these superintendents created the Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses of the United States and Canada (later renamed the National League for Nursing Education [NLNE] in 1912). The goals of the Society of Superintendents were “to promote fellowship of members, to establish and maintain a universal standard of training, and to further the best interests of the nursing profession” (American Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses, 1897, p. 4). Along with the difficulties nursing superintendents faced with the education of nurses, data released by the national census revealed to the public that there were almost 109,000 “untrained nurses and midwives competing with 12,000 graduate nurses,” for nursing positions (U.S. Bureau of Census, 1900, p. xxiii). While the NLNE was concerned with the educational standards for nurses, the Nurses’ Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada (renamed the American Nurses Association [ANA] in 1912) focused on achieving legal recognition for trained nurses. To protect the public from nurses who lacked formal training, the Nurses’ Associated Alumnae began to pursue legal registration for trained nurses. Superintendent Isabel Hampton argued in support of this measure, because at that time a trained nurse meant “… anything, everything, or next to nothing” (Hampton, 1893/1949, p. 5). Securing legal recognition was seen as a way to counter the prevailing belief in society that “an ignorant woman, who was not fit for anything else, is good enough for a nurse” (Draper, 1893/1949, p. 151). The Nurses’ Associated Alumnae, composed of alumnae associations from schools of nursing, quickly moved to establish associated state organizations so that nurses could undertake the necessary political lobbying for the enactment of state registration laws. Their mission was to “strengthen the union of nursing organizations, to elevate nursing education, [and] to promote ethical standards” for the profession (Nurses’ Associated Alumnae, 1902, p. 766). The two substantive issues that concerned this group were the establishment and maintenance of a journal, the American Journal of Nursing, and securing state registration for nurses. The latter was of major importance because it “would achieve legal recognition of nursing as a profession and provide a means for distinguishing trained nurses from those who purported to be but whose preparation for the practice of nursing fell short of standards (Daisy, 1996, p. 35). The efforts of the Associated Alumnae resulted in nursing registration legislation in March 1903 in North Carolina, followed by New Jersey, New York, and Virginia later that same year. These acts defined for the public that a “registered nurse” had attended an acceptable nursing program and passed a board evaluation examination. Still lacking, however, were universal educational standards and an agreed-upon definition of professional nursing practice. Following the enactment of nurse licensure, leaders of the profession created state nursing boards and empowered them to use their legal authority to protect the public from unfit nurses. Ironically, women who lacked the legal right to vote in 1910 aided 27 states in enacting nurse registration laws. By 1923 all the states in the nation, along with Hawaii and the District of Columbia, possessed nurse registration laws (Bullough, 1975). Although many nursing leaders praised the accomplishment of the passing of registration laws for nurses, Annie Goodrich, Inspector of Nurses Training Schools for the New York State Education Department (and later dean of the Yale School of Nursing), noted that the boards were “conspicuously weak and inefficient in every state” (Goodrich, 1912, p. 1001). Employment opportunities for graduate nurses in the early 20th century were, for the most part, limited to caring for ill persons in their own homes; hospitals were seen as places to care for those who had no one else to care for them. Nursing students staffed the hospital, under the direction of the head nurse, who was usually a training school graduate. Therefore after graduation, graduates eagerly donned their white uniforms, caps, and nursing pins and joined a “registry,” allowing them to practice as private duty nurses in patients’ homes. Nurse registries, operated by hospitals, professional organizations, or private businesses, provided sites where the public could acquire the services of these private duty nurses. Families could contract for the services of a nurse for a day or a few hours to care for their loved ones either at home or in the hospital (Whelan, 2005). Although physicians’ orders were required, private duty in the home provided graduate nurses with the venue and the opportunity to break away from the rigid hospital routine and allowed for a more autonomous practice. These nurses provided care to patients with contagious diseases such as pneumonia and typhoid fever, aided women in childbirth, and supported those with fractures, infected wounds, strokes, and mental diseases. Private duty nurses lived with and worked for their patients, providing 24-hour care, often for weeks at a time (Stoney, 1919). Private duty nurses were usually employed only by middle- and upper-class households. Graduate nurses were generally pleased with their role as private duty nurses, but their employment was seasonal and sporadic. Because of the onslaught of contagious diseases in the cold months of the year, winters were busy and summers slow. Average annual income of a private duty nurse in the late 1910s was approximately $950, a sum that sustained her but left little savings for future needs (Reverby, 1987). Nonetheless, the trend toward private duty prevailed. By the 1920s, 70% to 80% of graduates worked in private duty. During the early 20th century, however, new medical discoveries led the public to hospitals for the latest in scientific care. Hospitals could provide blood and urine tests and x-rays, as well as perform surgery in modern surgical amphitheaters equipped with anesthetics (Howell, 1996). To deal with the increasing hospital census in the 1920s, nursing superintendents were pressured to admit more students into school programs. In turn, the increase of nursing students resulted in an increase of graduate nurses, thus creating a surplus. In 1926 the ANA and NLNE grew concerned about the economic plight of graduate nurses and authorized a comprehensive study of the working conditions of graduate nurses. The study, later known as the Burgess Report, documented that registered nurses faced widespread underemployment and harsh working conditions (Burgess, 1928). Another survey, conducted by Janet Geister, underscored the private duty nurses’ economic plight. According to Geister, 80% of nurses’ patient cases lasted only 1 day. This level of employment earned them approximately $31.26 a week, or 49 cents an hour—less than the income of scrubwomen, who earned 50 cents an hour (Geister, 1926). A few years later, with the collapse of the stock market and the subsequent economic depression that enveloped the country, even the lowest-paying jobs for private duty nurses disappeared. Private duty nursing became a “luxury” few could afford. This combined with the fact that patients preferred the scientific medical care offered in hospitals created a gloomy occupation outlook for private duty nurses. Despite the increasing complexity of hospital work, administrators and physicians simply could not justify hiring large numbers of graduate nurses when they had an inexpensive nursing student workforce readily available. Employing registered nurses would increase overhead costs immensely; moreover, physicians were afraid that graduate nurses would get involved with decision making in the hospital. As noted by one physician-hospital administrator, nursing was “only a differentiation of domestic duty” and the graduate nurse a “half-baked social product thrust into the fulfillment of an uncertain social need” (Howard, 1912). Although private duty nurses outnumbered other professional nurses, and many were members of the ANA Private Duty Nurses Section, they lacked leaders at both the national and state levels. Without leaders, private duty nurses failed to unite or develop effective strategies to upgrade their clinical standards or improve their economic conditions. However, many private duty nurses, who diligently upgraded their medical knowledge and skills, did achieve individual distinction and respect in their communities. These nurses fared much better economically than other graduates because physicians and families requested their services. For most graduates, however, job opportunities would not improve until the late 1930s when hospitals began to add registered nurses to their staffs (Roberts, 1954). There were nursing infants, many of them with the summer bowel complaint that sent infant mortality soaring during the hot months; there were children with measles, not quarantined; there were children with ophthalmia, a contagious eye disease; there were children scarred with vermin bites; there were adults with typhoid; there was a case of puerperal septicemia, lying on a vermin-infested bed without sheets or pillow cases; a family consisting of a pregnant mother, a crippled child and two others living on dry bread …; a young girl dying of tuberculosis amid the very conditions that had produced the disease (Wald, quoted in Duffus, 1938, p. 43). Thus in 1895 Wald and her colleague Mary Brewster founded the Henry Street Settlement House and Henry Street Visiting Nurse Services (Wald, 1938; Keeling, 2007). Wald’s work promoting health and preventing disease made an enormous impact on the lives of the poverty-stricken immigrants on New York City’s Lower East Side. The visiting nurses’ work quickly expanded to new services, including school nursing, industrial nursing, tuberculosis nursing, and infant welfare nursing. Later, Wald joined forces with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to send nurses into the homes of the company’s customers when they became ill (Struthers, 1917; Hamilton, 1989). In 1912 Wald founded the National Organization for Public Health Nursing (NOPHN)—nursing’s first specialty organization. That year there were approximately 3000 public health nurses working throughout the United States (Gardner, 1936). The major goals of NOPHN were to develop adequate numbers of public health nurses to meet the needs of the public and to link the emerging field of public health nursing to preventive medicine (Brainard, 1922). The creation of the federally based Children’s Bureau, also in 1912, as well as the passage of the Maternal and Infant Act (Sheppard-Towner) in 1921, reflected the federal government’s growing concern for the health of women and children. Public health nurses served as the backbone of this program as they traveled to remote areas in their states to bring clinics and health services to those most in need. Although the federal programs experienced opposition, especially from physicians, in the 8 years of their existence, the programs demonstrated the effectiveness of nurses in the screening of ill patients and referring those patients to physicians. The programs also brought health education to thousands of American families (Meckel, 1990). The development of community health nursing was important to the nation and to the nursing profession because it brought essential health services to the public. It also provided nurses with unique opportunities to integrate epidemiological knowledge and sanitation practices—as well as medical science—into the care and education of the public. Community nurses, using their hospital training, expanded the domain of nursing practice to include individuals, families, and communities. Their pioneering activities in health promotion and disease prevention, along with their stand on health and welfare issues, have proven vital in shaping America’s health system and the discipline of nursing (Bullough & Bullough, 1978). also served. In addition, Catholic nuns and Lutheran deaconesses provided care to the soldiers. However, there were no trained nurses and no military nurses at this time. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, trained nurses volunteered to serve in the army to care for soldiers suffering from yellow fever. This experience helped to convince military physicians and Congress that trained female nurses should become permanent members of the nation’s defense forces. It set the stage for the creation of the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and the Navy Nurse Corps in 1908 (Sarnecky, 1999). Both the Army Nurse Corps and the Navy Nurse Corps would serve in the Great War during the next decade. Although the United States’ formal involvement in World War I (1917 to 1919) was short, it was important in documenting the ability of trained nurses to work effectively in war. Nursing leaders cooperated with the federal government in a major recruitment and mobilization campaign to remedy the profound shortage of nursing personnel that existed in the spring of 1917. As part of that effort, the American Red Cross, led by Jane Delano, conducted an ambitious campaign to draw women into the war effort. Meanwhile, nursing leaders debated the issue of who was qualified to serve in the war. In the existing environment of patriotic fervor, many women of higher society, as well as numerous minimally trained nurses’ aides, wished to serve by performing the work of trained nurses; however, leaders of the nursing profession insisted on the use of properly trained nurses. A dual solution was reached: the creation of an innovative program at Vassar College and the establishment of an Army School of Nursing, both designed to increase the supply of trained nurses for the military (Clappison, 1964). During the war, even those who were properly trained faced extreme challenges. Tested by harsh conditions on the European front, severe nursing shortages, and the occurrence of a devastating influenza pandemic, white female nurses demonstrated their effectiveness (Telford, 2007). Because of the segregated nature of American society at the time, black nurses, both male and female, were for the most part, denied the opportunity to participate.

Historical Development of Professional Nursing in the United States

![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() The Historical Evolution of Nursing

The Historical Evolution of Nursing

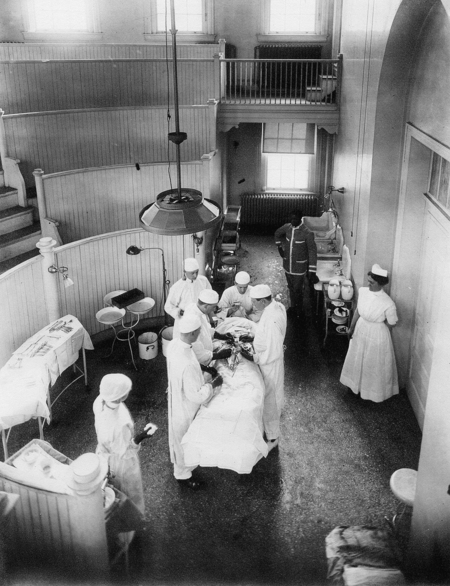

THE BEGINNING OF NURSING TRAINING PROGRAMS

NURSING SUPERINTENDENTS AND THE BEGINNING OF PROFESSIONALISM THROUGH ORGANIZATION

NURSING PRACTICE IN EARLY 20TH-CENTURY AMERICA

SOCIAL REFORM THROUGH COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSING

The NURSE’S ROLE IN WAR

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access