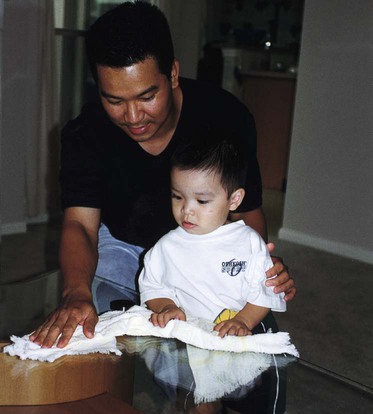

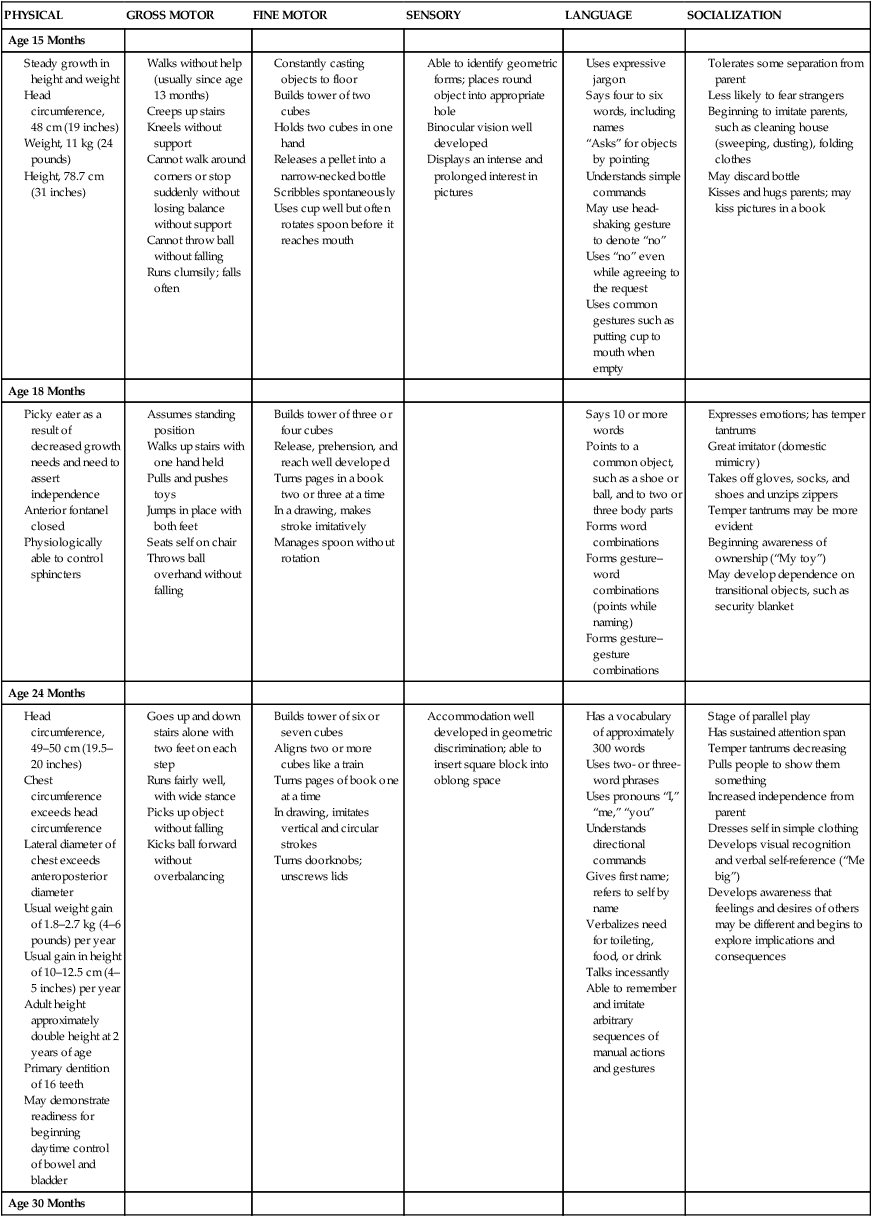

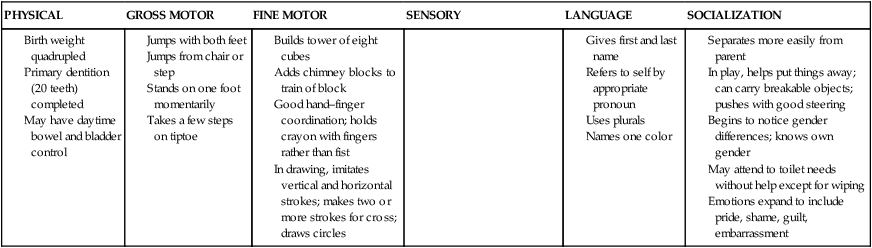

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Identify the major biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, and social developments during the toddler years. • Relate separation anxiety and negativism to developmental tasks. • Recognize readiness for toilet training and offer parents guidelines. • Help parents foster toddlers’ language development. • Provide parents with guidelines for handling temper tantrums. • Provide parents with feeding recommendations. • Outline a preventive dental hygiene plan for toddlers. • Provide anticipatory guidance to parents regarding injury prevention based on the toddler’s developmental achievements. http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/essentials • Differentiation of self from others, particularly the mother • Toleration of separation from parent • Ability to withstand delayed gratification • Control over bodily functions • Acquisition of socially acceptable behavior • Verbal means of communication • Ability to interact with others in a less egocentric manner According to Erikson (1963), the developmental task of toddlerhood is acquiring a sense of autonomy while overcoming a sense of doubt and shame. As infants gain trust in the predictability and reliability of their parents, environment, and interactions with others, they begin to discover that their behavior is their own and that it has a predictable, reliable effect on others. Although they realize their will and control over others, they are confronted with the conflict of exerting autonomy and relinquishing the much-enjoyed dependence on others. Whereas exerting their will has definite negative consequences, retaining dependent, submissive behavior is generally rewarded with affection and approval. However, continued dependence creates a sense of doubt regarding their potential capacity to control their actions. This doubt is compounded by a sense of shame for feeling this urge to revolt against others’ will and a fear that they will exceed their own capacity for manipulating the environment. Skillful monitoring and balance of controls by parents allows a growing rate of realistic successes and the emergence of autonomy. Several characteristics, especially negativism and ritualism, are typical of toddlers in their quest for autonomy. As toddlers attempt to express their will, they often act with negativism, the persistent negative response to requests. The words “no” or “me do” can be their sole vocabulary. Emotions become strongly expressed, usually in rapid mood swings. One minute, toddlers can be engrossed in an activity, and the next minute they might be angry because they are unable to manipulate a toy or open a door. If scolded for doing something wrong, they can have a temper tantrum and almost instantaneously pull at the parent’s legs to be picked up and comforted. Understanding and coping with these swift changes is often difficult for parents. Many parents find the negativism exasperating and, instead of dealing constructively with it, give in to it, which further threatens children in their search for learning acceptable methods of interacting with others (see Temper Tantrums, p. 389, and Negativism, p. 390). In contrast to negativism, which frequently disrupts the environment, ritualism, the need to maintain sameness and reliability, provides a sense of comfort. Toddlers can venture out with security when they know that familiar people, places, and routines still exist. One can easily understand why any change in the daily routine represents such a threat to these children. Without comfortable rituals, they have little opportunity to exert autonomy. Consequently, dependency and regression occur (see Regression, p. 390). With the development of the ego, children further differentiate themselves from others and expand their sense of trust within themselves. But as they begin to develop awareness of their own will and capacity to achieve, they also become aware of their ability to fail. This ever-present awareness of potential failure creates doubt and shame. Successful mastery of the task of autonomy necessitates opportunities for self-mastery while withstanding the frustration of necessary limit setting and delayed gratification. Opportunities for self-mastery are present in appropriate play activities, toilet training, the crisis of sibling rivalry, and successful interactions with significant others (Fig. 12-1). In the fifth stage of the sensorimotor phase, tertiary circular reactions (13–18 months of age), the child uses active experimentation to achieve previously unattainable goals (see Cognitive Development, Chapter 10). Newly acquired physical skills are increasingly important for the function they serve rather than for the acts themselves. Children incorporate the old learning of secondary circular reactions with new skills and apply the combined knowledge to new situations, with emphasis on the results of the experimentation. In this way, there is the beginning of rational judgment and intellectual reasoning. During this stage, there is further differentiation of oneself from objects. This is evident in children’s increasing ability to venture away from their parents and to tolerate longer periods of separation. Imitation displays deeper meaning and understanding. There is greater symbolization to imitation. Children are acutely aware of others’ actions and attempt to copy them in gestures and in words. Domestic mimicry (imitating household activities) and sex-role behavior become increasingly common during this period and during the second year. Identification with the parent of the same gender becomes apparent by the second year and represents the child’s intellectual ability to differentiate different models of behavior and to imitate them appropriately (Fig. 12-2). At approximately 2 years of age, children enter the preconceptual phase of cognitive development, which lasts until about age 4 years. The preconceptual phase is a subdivision of the preoperational phase, which spans ages 2 to 7 years. The preconceptual phase is primarily one of transition that bridges the purely self-satisfying behavior of infancy and the rudimentary socialized behavior of latency. Preoperational thought implies that children cannot think in terms of operations—the ability to manipulate objects in relation to each other in a logical fashion. Rather, toddlers think primarily on the basis of their perception of an event. Problem solving is based on what they see or hear directly rather than on what they recall about objects and events. Several characteristics are unique to preoperational thought (Box 12-1). Spiritual development in children is often discussed in terms of the child’s developmental level because the evolution of spirituality often parallels cognitive development (Elkins and Cavendish, 2004). The child’s family and environment strongly influence the child’s perception of the world around him or her, and this often includes spirituality. Furthermore, family values, beliefs, customs, and expressions of these influence the child’s perception of his or her spiritual self (Elkins and Cavendish, 2004). Neuman (2011) proposes that Fowler’s (1981) stages of faith be used to better understand children and spirituality; she provides an excellent overview of the stages of faith in childhood. The relationship between spirituality, illness in childhood, and nursing has been studied in the context of suffering, terminal illness such as cancer, and end-of-life care. In the past decade, there has been an increased interest in and focus on spiritual care in adults and children as further understanding of the influence of one’s spirituality on health, illness, and well-being has progressed. Toddlers learn about God through the words and the actions of those closest to them. They have only a vague idea of God and religious teachings because of their immature cognitive processes; however, if God is spoken about with reverence, young children associate God with something special. During this period, the assignment of powerful religious symbols and images is strongly influenced by the manner in which it is presented; therein lies the potential for the development of guilt and fear or, conversely, love and companionship with religious symbols (Roehlkepartain, King, Wagener, and others, 2006). Toddlers are said to be in the intuitive-projective phase of Fowler’s (1981) faith construct wherein thinking is largely based on fantasy and rather fluid in relation to reality and fantasy. God may be described as being around like air by the toddler because of the fluidity in dividing fantasy and reality (Neuman, 2011). Toddlers begin to assimilate behaviors associated with the divine (folding hands in prayer). Routines such as saying prayers before meals or at bedtime can be important and comforting. Because toddlers tend to find solace in ritualistic behavior and routines, they incorporate routines associated with religious practices into their behavioral patterns without understanding all of the implications of the rituals until later. Near the end of toddlerhood, when children use preoperational thought, there is some advancement of their understanding of God. Religious teachings, such as reward or fear of punishment (heaven or hell) and moral development (see Chapter 5), may influence their behavior (Fosarelli, 2003). Children in this age group are learning vocabulary associated with anatomy, elimination, and reproduction. Certain associations between words and functions become significant and can influence future sexual attitudes. For example, if parents refer to the genitalia as dirty, especially in the context of elimination, this association between “genitalia” and “dirty” may be transferred to sexual functions later in life. Sex-role differences become obvious to children and are evident in much of toddlers’ imitative play. Although current research indicates that prenatal exposure to testosterone strongly influences the individual’s gender identity, researchers also indicate that there are sensitive periods (e.g., puberty) that may also have an influence on the development of gender identity (Berenbaum and Beltz, 2011; Hines, 2011; Savic, Garcia-Falqueras, and Swaab, 2010). A sense of maleness or femaleness, or gender identity, is formed by age 3 years, and the child’s feelings about being male or female begin to form (Fonseca and Greydanus, 2007). Early attitudes are formed about affectionate behaviors between adults from observing parental and other adult intimate or sensual activities. (See also Sex Education, Chapter 13.) The quality of relationships with parents is important to the child’s capacity for sexual and emotional relationships later in life. According to Harpaz-Rotem and Bergman (2006), the separation-individuation phase encompasses the phenomenon of rapprochement; as a toddler separates from the mother and begins to make sense of experiences in the environment, he or she is drawn back to the mother for assistance in verbally articulating the meaning of the experiences. Developmentally, the term rapprochement means the child moves away and returns for reassurance. If the mother’s response to the toddler is inappropriate, the toddler may experience insecurity and confusion. Transitional objects, such as a favorite blanket or toy, provide security for children, especially when they are separated from their parents, dealing with a new stress, or just fatigued (Fig. 12-3). Security objects often become so important to toddlers that they refuse to let them be taken away. Such behavior is normal; there is no need to discourage this tendency. During separations, such as daycare, hospitalization, or even staying overnight with a relative, transitional objects should be provided to minimize any fear or loneliness. At age 1 year, children use one-word sentences or holophrases. The word “up” can mean “pick me up” or “look up there.” For children, the one word conveys the meaning of a sentence, but to others, it may mean many things or nothing. At this age, about 25% of the vocalizations are intelligible. By the age of 2 years, children use multiword sentences by stringing together two or three words, such as the phrases “mama go bye-bye” or “all gone,” and approximately 65% of their speech is understandable. By 3 years, children put words together into simple sentences, begin to master grammatical rules, acquire five or six new words daily, know their age and gender, and can count three objects correctly. Looking at books during this period provides an ideal setting for further language development (Feigelman, 2011). Authorities have evaluated the impact of television viewing on toddler language development and found that those who started watching television at younger than 12 months of age and who watched longer than 2 hours per day had significant language delays (Chonchaiva and Pruksananonda, 2008). Adult–child conversations with infants and toddlers have been shown to positively affect language development; the researchers recommend reading, storytelling, and interactive adult–child communication (Zimmerman, Gilkerson, Richards, and others, 2009). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Council on Communications and Media (2011) reaffirms that televised or recorded media usage in children less than 2 years of age decreases language skills, as well as the time parents interact with the child. Furthermore, educational programs have not been shown to increase cognitive skills in young children (AAP, Council on Communications and Media, 2011). Gestures precede or accompany each of the language milestones up to 30 months of age (putting phone to ear, pointing). After sufficient language development, gestures phase out, and the pace of word learning increases (Bates and Dick, 2002). Play magnifies toddlers’ physical and psychosocial development. Interaction with people becomes increasingly important. The solitary play of infancy progresses to parallel play—toddlers play alongside, not with, other children. Although sensorimotor play is still prominent, there is much less emphasis on the exclusive use of one sensory modality. Toddlers inspect toys, talk to toys, test toys’ strength and durability, and invent several uses for toys. Imitation is one of the most distinguishing characteristics of play and enriches children’s opportunity to engage in fantasy. With less emphasis on gender-stereotyped toys, play objects such as dolls, carriages, dollhouses, balls, dishes, cooking utensils, child-size furniture, trucks, and dress-up clothes are suitable for both genders (Fig. 12-4); however, whereas boys may be more interested than girls in activities related to trucks, trailers, action figures, and building blocks, girls may prefer doll-related activities. Increased locomotive skills make push–pull toys, straddle trucks or cycles, a small gym and slide, balls of various sizes, and riding toys appropriate for energetic toddlers. Finger paints; thick crayons; chalk; blackboard; paper; and puzzles with large, simple pieces use toddlers’ developing fine motor skills. Interlocking blocks in various sizes and shapes provide hours of fun and, during later years, are useful objects for creative and imaginative play. The most educational toy is the one that fosters the interaction of an adult with a child in supportive, unconditional play. Toys should not be substitutes for the attention of devoted caregivers, but toys can enhance these interactions (Glassy, Romano, and Committee on Early Childhood, 2003). Parents and other providers are encouraged to allow children to play with a variety of simple toys that foster creative thinking (e.g., blocks, dolls, and clay) rather than passive toys that the child observes (battery-operated or mechanical). Active play time should also be encouraged over the use of computer or video games, which are more passive (Ginsburg and AAP, Committee on Communications, 2007). Certain aspects of play are related to emerging linguistic abilities. Talking is a form of play for toddlers, who enjoy musical toys such as age-appropriate compact disc (CD) players, “talking” dolls and animals, and toy telephones. Children’s television programs are appropriate for some children over age 2 years, who learn to associate words with visual images. However, total media time should be limited to 1 hour or less of quality programming per day. Parents are encouraged to allow the child to engage in unstructured playtime, which is considered much more beneficial than any electronic media exposure (AAP, Council on Communications and Media, 2011). Toddlers also enjoy “reading” stories from a picture book and imitating the sounds of animals. Selection of appropriate toys must involve safety factors, especially in relation to size and sturdiness. The oral activity of toddlers puts them at risk for aspirating small objects and ingesting toxic substances. Parents need to be especially vigilant of toys played with in other children’s homes and toys of older siblings. Toys are a potential source of serious bodily damage to toddlers, who may have the physical strength to manipulate them but not the knowledge to appreciate their danger (Stephenson, 2005). Government agencies do not inspect and police all toys on the market. Therefore, adults who purchase play equipment, supervise purchases, or allow children to use play equipment need to evaluate its safety, including toys that are gifts or those that are purchased by the children themselves. Adults should also be alert to notices of toys determined to be defective and recalled by the manufacturers. Parents and health care workers can obtain information on a variety of recalled products and can report potentially dangerous toys and child products to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission* or, in Canada, the Canadian Toy Testing Council.† Printable tips on toy safety are also available from Safe Kids Worldwide (http://www.safekids.org). Table 12-1 summarizes the major features of growth and development for the age groups of 15, 18, 24, and 30 months. TABLE 12-1 GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT DURING THE TODDLER YEARS Voluntary control of the anal and urethral sphincters is achieved sometime after the child is walking, probably between ages 18 and 24 months. However, complex psychophysiologic factors are required for readiness. The child must be able to recognize the urge to let go and hold on and be able to communicate this sensation to the parent. In addition, some motivation is probably involved in the desire to please the parent by holding on rather than pleasing oneself by letting go. Cultural beliefs may also affect the age at which children demonstrate readiness (Feigelman, 2011). Schmitt (2004) notes that comparative studies over the past 5 decades indicate that children in the 1990s in the United States were toilet trained at a later age (18 months in the 1960s vs. 36 months in the 1990s); one possible contributing factor is the availability and convenience of disposable diapers. Another study found that the child’s average age at initiation of toilet training was 20.6 months (Horn, Brenner, Rao, and others, 2006). Five markers signal a child’s readiness to toilet train: bladder readiness, bowel readiness, cognitive readiness, motor readiness, and psychologic readiness (Schmitt, 2004). According to some experts, physiologic and psychologic readiness is not complete until ages 22 to 30 months (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, and others, 2002); however, Schmitt (2004) emphasizes that parents should begin preparing their children for toilet training earlier than 30 months. By this time, children have mastered the majority of essential gross motor skills, can communicate intelligibly, are in less conflict with their parents in terms of self-assertion and negativism, and are aware of the ability to control the body and please their parents. There is no universal right age to begin toilet training or an absolute deadline to complete training. An important role for the nurse is to help parents identify the readiness signs in their children (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).* On average, girls are developmentally ready to begin toilet training 2 to

Health Promotion of the Toddler and Family

Promoting Optimal Growth and Development

Psychosocial Development

Developing a Sense of Autonomy (Erikson)

Cognitive Development: Sensorimotor and Preoperational Phase (Piaget)

Tertiary Circular Reactions

Invention of New Means Through Mental Combinations

Preoperational Phase

Spiritual Development

Development of Gender Identity

Social Development

Language

Play

Coping with Concerns Related to Normal Growth and Development

Toilet Training

![]() Case Study—Toilet Training/Toddler Development

Case Study—Toilet Training/Toddler Development

months before boys (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, and others, 2002).

months before boys (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, and others, 2002).

years of age. The rate of increase in height also slows. The usual increment is an addition of 7.5 cm (3 inches) per year and occurs mainly in elongation of the legs rather than the trunk. The average height of a 2-year-old child is 86.6 cm (34 inches). In general, adult height is about twice the 2-year-old child’s height. Accurate measurement of height and weight during the toddler years should reveal a steady growth curve that is steplike in nature rather than linear (straight), which is characteristic of the growth spurts during the early childhood years.

years of age. The rate of increase in height also slows. The usual increment is an addition of 7.5 cm (3 inches) per year and occurs mainly in elongation of the legs rather than the trunk. The average height of a 2-year-old child is 86.6 cm (34 inches). In general, adult height is about twice the 2-year-old child’s height. Accurate measurement of height and weight during the toddler years should reveal a steady growth curve that is steplike in nature rather than linear (straight), which is characteristic of the growth spurts during the early childhood years. years of age.

years of age. years, they can jump using both feet, stand on one foot for a second or two, and manage a few steps on tiptoe. By the end of the second year, they can stand on one foot, walk on tiptoe, and climb stairs with alternate footing.

years, they can jump using both feet, stand on one foot for a second or two, and manage a few steps on tiptoe. By the end of the second year, they can stand on one foot, walk on tiptoe, and climb stairs with alternate footing.