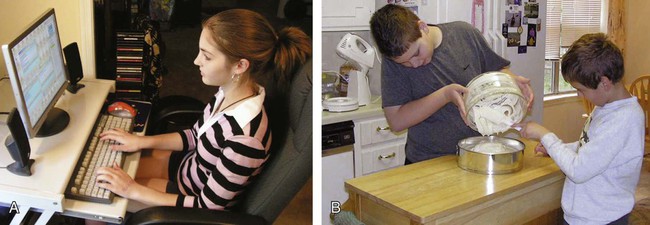

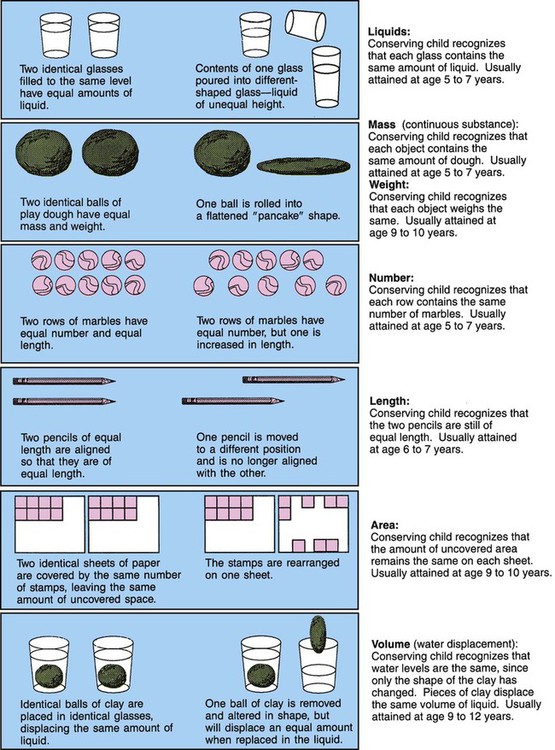

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Describe the physical, cognitive, and moral changes that take place during the middle childhood years. • Describe ways to help a child develop a sense of accomplishment. • Demonstrate an understanding of the changing interpersonal relationships of school-age children. • Discuss the role of the peer group in the socialization of the school-age child. • Discuss the role of schools in the development and socialization of the school-age child. • Outline an appropriate health teaching plan for the school-age child. • Plan a sex education session for a group of school-age children. • Identify the causes and discuss the preventive aspects of injury in middle childhood. http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/essentials Specific physiologic and anatomic characteristics are typical of children in middle childhood. Facial proportions change as the face grows faster in relation to the remainder of the cranium. The skull and brain grow very slowly during this period and increase little in size. Because all of the primary (deciduous) teeth are lost during this age span, middle childhood is sometimes known as the age of the loose tooth (Fig. 15-1). The early years of middle childhood, when the new secondary (permanent) teeth appear too large for the face, are known as the ugly duckling stage. Interests expand in the middle years, and with a growing sense of independence, children want to engage in tasks that can be carried through to completion (Fig. 15-2). They gain satisfaction from independent behavior in exploring and manipulating their environment and from interaction with peers. Often the acquisition of skills provides a way to achieve success in social activities. Reinforcement in the form of grades, material rewards, additional privileges, and recognition provides encouragement and stimulation. One cognitive task of school-age children is mastering the concept of conservation (Fig. 15-3). At an early age (5–7 years), children grasp the concept of reversibility of numbers as a basis for simple mathematics problems (e.g., 2 + 4 = 6 and 6 – 4 = 2). They learn that simply altering their arrangement in space does not change certain properties of the environment, and they are able to resist perceptual cues that suggest alterations in the physical state of an object. For example, they recognize that changing the shape of a substance such as a lump of clay does not alter its total mass. They no longer perceive a tall, thin glass of water as containing a greater volume than a short, wide glass; they can distinguish between the weight of items regardless of their size. They recognize that size is not necessarily related to weight or volume. There is a developmental sequence in children’s capacity to conserve matter. Conservation of mass usually is accomplished first, weight some time later, and volume last. Third, the interaction among peers leads to the formation of intimate friendships between same-sex peers. The school-age period is the time when children have “best friends” with whom they share secrets, private jokes, and adventures; they come to one another’s aid in times of trouble. In the course of these friendships, children also fight, threaten each other, break up, and reunite. These relationships, in which the child experiences love and closeness with a peer, may be important as a foundation for relationships in adulthood (Fig. 15-4). Peer-group identification and association are essential to a child’s socialization. Poor relationships with peers and a lack of group identification can contribute to bullying. Bullying is any recurring activity that intends to cause harm, distress, or control towards another in which there is a perceived imbalance of power between the aggressor(s) and the victim (Lamb, Pepler, and Craig, 2009). Although bullying can occur in any setting, it most often occurs at school during unstructured times such as recess (Arseneault, Bowes, and Shakoor, 2010). Children who are targeted for bullying often have internalizing characteristics such as withdrawal, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and reduced assertiveness that may make them an easy target for bullying (Arseneault, Bowes, and Shakoor, 2010). Bullies are generally defiant toward adults, antisocial, and likely to break school rules. They have dominant personalities, may come from homes where parental involvement and nurturing are lacking, and may experience or witness violence or abuse at home (Bowes, Arseneault, Maughan, and others, 2009). Boys who bully tend to use physical force, referred to as direct bullying, but girls usually use indirect bullying methods, such as exclusion, gossip, or rumors (Arseneault, Bowes, and Shakoor, 2010). Cyberbullying is a new form of bullying and involves the use of cellular telephones, digital cameras, or social networking Internet sites to cause distress on an individual (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention, 2009). The long-term consequences of bullying are significant. Chronic bullies seem to continue their behaviors into adulthood, negatively influencing their ability to develop and maintain relationships. Victims of bullying often experience psychological distress such as worry, sadness, anxiety, depression, and nightmares and can have increased self-harm behaviors, social isolation, suicidal ideation, and violent behaviors (Arseneault, Bowes, and Shakoor, 2010). School personnel play an important role in implementing antibullying interventions in schools; however, research has recognized that involving the whole family in antibullying programs greatly increases success (Arseneault, Bowes, and Shakoor, 2010). There are also dangers in peer group attachments that are too strong. Peer pressures force some children to take risks or engage in behaviors that are against their better judgment. A child’s membership in a gang is associated with marked increases in serious delinquent behavior (Fisher, Montgomery, and Gardner, 2008). Peer group activities that result in unlawful or criminal gang violence are increasing in the United States. An integration of family-centered and school-based programs is needed to reduce the influences for children to become affiliated with gangs. The newly acquired skill of reading becomes increasingly satisfying as school-age children expand their knowledge of the world through books (Fig. 15-5). School-age children never tire of stories and, as with preschool children, love to have stories read aloud. They also enjoy sewing, cooking, carpentry, gardening, and creative activities such as painting. Many creative skills such as music and art, as well as athletic skills such as swimming, karate, dancing, and skating, are learned during these years and continue to be enjoyed into adolescence and adulthood (Fig. 15-6). Table 15-1 summarizes the major developmental achievements of the school-age years. TABLE 15-1 GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT DURING THE SCHOOL-AGE YEARS Height and weight gain continues slowly Weight, 16–26.3 kg (35.5–58 pounds) Height, 106.7–122 cm (42–48 inches) Central mandibular incisors erupt Often returns to finger feeding

Health Promotion of the School-Age Child and Family

Promoting Optimal Growth and Development

Biologic Development

Proportional Changes

Psychosocial Development: Developing a Sense of Industry (Erikson)

Cognitive Development (Piaget)

Social Development

Social Relationships and Cooperation

Clubs and Peer Groups

Play

Quiet Games and Activities

Developing a Self-Concept

Developing a Body Image

PHYSICAL AND MOTOR

MENTAL

ADAPTIVE

PERSONAL-SOCIAL

Age 6 Years

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Health Promotion of the School-Age Child and Family

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access