Chapter 14 Health promotion in the workplace

Overview

The workplace is significant both in affecting people’s health and as a context in which to promote health. Employment rates in the UK have been rising. Statistics for the last quarter of 2007 show that 74.7% of people of working age, or 29.4 million people, were employed (www.statistics.gov.uk). Promoting health in the workplace will therefore reach a large percentage of the adult population, and will have an impact on a setting where many adults spend a considerable amount of their time.

Why is the workplace a key setting for health promotion?

There are four main reasons for prioritizing the workplace. First, the workplace gives access to a target group, healthy adults, especially men, who are often difficult to reach in other ways. Recent projections suggest that by 2020 32.1 million people will be economically active (Madouros 2006), which represents an increase of 6.7% from 2005. Employees in the workplace are a captive audience for health promotion. It is easy to follow up interventions and encourage participation in health programmes because there are established modes of communication. The cohesion of the working community also provides peer pressure and support. The second reason for promoting health in the workplace is to ensure that people are protected from the harm to their health that certain jobs may cause.

Work-related ill health – U.K. statistics for the year 2006–2007

241 workers were killed at work (an 11% increase on 2005–2006)

141,350 employees suffered serious injuries at work

36 million days were lost overall (1.5 days per worker), with 30 million due to work-related ill health and 6 million due to workplace injury (Health and Safety Executive (HSE) 2007).

Thirdly, there are economic benefits associated with healthy workplaces (Wanless 2004). American research studies provide evidence that workplace health promotion programmes are associated with lower medical and insurance costs, decreased absenteeism and enhanced performance, productivity and morale (www.uclan.ac.uk/facs/health/hsdu/settings/workplace/htm). The cost of sick leave and incapacity benefit averaged £476 per worker in 2002 (Dooris & Hunter 2007). Research has shown that employees who have three or more risk factors (e.g. smoking, overweight, excessive alcohol intake, physical inactivity) are likely to have 50% more sickness absence from work than employees with no risk factors (Shain & Kramer 2004). Investing in health and preventing ill health increase productivity and staff retention. The average cost–benefit ratio for a variety of health promotion programmes operated by large American companies is significant – just over a fourfold return on each dollar invested (Shain & Kramer 2004). Adopting a healthy workplaces approach therefore makes sound business sense.

Economic benefits of workplace health promotion programmes

The relationship between work and health

The relationship between work and health is complex. In general, attention has focused on the effects of work on health, although it is also acknowledged that poor health will have negative effects on the capacity for paid employment. There is evidence that paid work is good for your health and unemployment can be linked to ill health (Waddell & Burton 2006). Work is beneficial for health because it provides an income, a sense of self-worth and social networks of colleagues and friends. However, work may also harm health, and most research has concentrated on this aspect of the relationship.

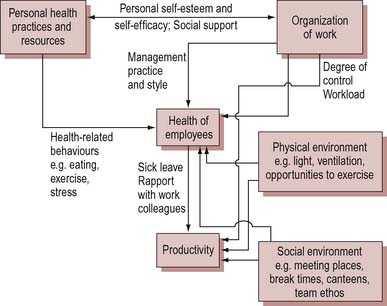

The workplace can affect health in many different ways. Figure 14.1 provides a means of classifying these different kinds of relationship.

Figure 14.1 The relationship between health and productivity in the workplace. From Shain & Kramer (2004).

Hazards tend to be what people think of first when health in the workplace is mentioned. Most legislation is directed towards the containment of hazards, and safety legislation has been enshrined in numerous Factory Acts since the mid 19th century. Work that involves handling hazardous or toxic materials may have a direct negative effect on health (e.g. cancers caused by asbestos or occupational asthma). Work which provides easy access to hazardous substances is also linked to associated ill health. For example, doctors and pharmacists have high rates of suicide associated with drug overdose. In 2000 the government set out, for the first time, overarching targets for significant improvements in workplace health and safety. The statistics for workplace deaths and injuries for 2006–2007 are mixed (HSE 2007; Health and Safety Commission 2007). Overall there has been progress in major injury reduction, but an increase in workplace deaths. Almost one-third of deaths occur in the construction sector, with agriculture, waste and recycling industries also implicated.

The workplace is characterized by fragmented information which is collected by different bodies (including the HSE and occupational health services). This poses obvious difficulties when trying to plan and implement a health promotion intervention. Health is often affected through risky behaviour or changed routines. Risky behaviour is the preferred explanation for most official accounts of accidents and injuries sustained in the workplace. There are extensive regulations to cover manual handling (Manual Handling Operations Regulations, amended in 2002) which require employers to provide training and equipment. Nevertheless, employees are expected to ‘take reasonable care for the health and safety of themselves and any others who may be affected by their acts and omissions’. This approach extends to the workplace the victim-blaming ideology of some brands of health promotion. Behaviour which carries health risks may be an integral part of the job or part of the work culture. For example, bartenders have high rates of alcohol-related ill health because drinking heavily is associated with work (Wilhelm et al. 2004).

Although the relationship is difficult to quantify, strong evidence implicating the importance to health of the general work environment is becoming available (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006). There is a body of research demonstrating that certain factors associated with some types of work, such as repetitive tasks, lack of autonomy and pressures to meet deadlines, have harmful effects on health. In particular, low control by workers over what they do and how they do it is associated with increased risk of ill health (Wilkinson 2006). Long-term exposure to stress results in poor health and may also lead to less healthy lifestyle choices, such as smoking. There is a growing acknowledgement of the impact of workplace stress on health:

In response to this situation, the HSE (2005) has produced management standards to support employers who wish to tackle this issue.

Stress in the workplace

A focus on individual stress can be counterproductive, leading to a failure to tackle the underlying causes of problems in the workplace. Evidence has shown that poor working arrangements, such as lack of job control or discretion, consistently high work demands and low social support, can lead to increased risks of CHD [coronary heart disease], musculoskeletal disorders, mental illness and sickness absence. The real task is to improve the quality of jobs by reducing monotony, increasing job control, and applying appropriate HR [human resources] practices and policies – organisations need to ensure they adopt approaches that support the overall health and well being of their employees (Department of Health 2004, Chapter 7 para 16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

BOX 14.1

BOX 14.1 BOX 14.2

BOX 14.2 BOX 14.3

BOX 14.3 BOX 14.4

BOX 14.4 BOX 14.5

BOX 14.5