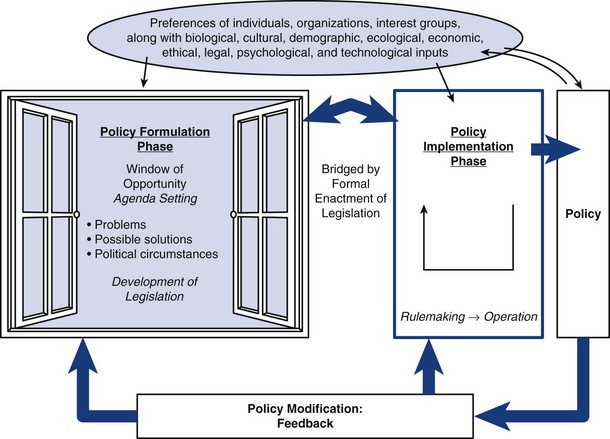

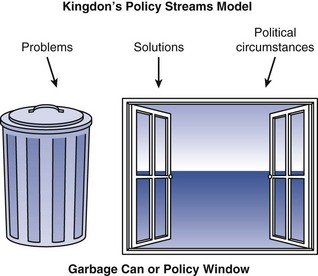

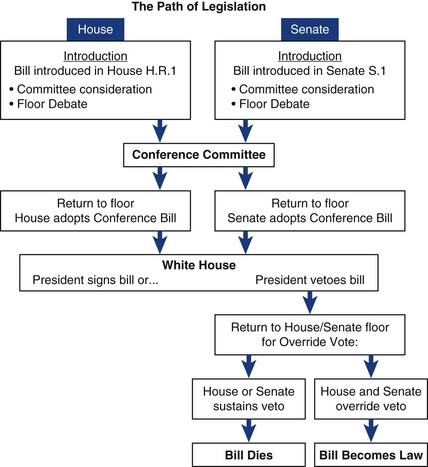

Chapter 22 Policy: Historic Core Function in Nursing Overview of the Health Policy Process: Politics Versus Policy Policy Frameworks and Key Concepts Policy Formulation: How a Bill Becomes Law Current and Emerging Health Policy Issues Relevant to Advanced Practice Nurses Context for Framing Advanced Practice Nurse Policy Issues: Cost, Quality, and Access Policy Initiatives in Health Reform Political Competence in the Policy Arena Health Policymaking: A Requisite Skill for Individual Advanced Practice Nurses Moving Advanced Practice Nurses Forward in Health Policy Engaging in policymaking is a core element of leadership to be cultivated by all APNs (see Chapter 11). In 2014, major health reform legislation, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011a), mandated health insurance coverage which will sweep an additional 50 million people into the U.S. health care delivery system. The system must accommodate this new surge in demand while raising the quality of care and lowering costs. Meeting these goals poses significant challenges. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the Future of Nursing (2010) has determined that nurses must be central to an improved U.S. health care system of the future. Of the eight specific IOM recommendations, three are highly pertinent to APNs engaging in policymaking: • Recommendation 1. Removal of scope of practice barriers so that nurses can function at the highest level of their education and training will require persistence and a strong degree of political competency because approximately 50% of the states have outdated nurse practice acts that do not reflect modern APN practice or national licensing standards. It will take a significant degree of political organizational networking, coalition building, campaigning, and educating the public to modernize the nation’s nurse practice acts. • Recommendation 7. Preparing and enabling nurses to lead change to advance health will require APNs to develop leadership skills, which include shaping and influencing policymaking at all levels. This recommendation will require APNs to become insightful knowledge sources on translational research and best practices, coupled with highly developed political competence. This recommendation emphasizes that nurses must be in key leadership positions across decision making bodies in the government and private sector. • Recommendation 8. Building an infrastructure for the collection and analysis of interprofessional health care workforce data requires nurses to be involved in improving the research enterprise around the U.S. nursing and health care workforce. This requires expertise in research methods and interprofessional collaboration skills so that nursing workforce data can better inform policymaking. Florence Nightingale spent much of her career in the halls of Parliament promoting policy change to improve quality, dignity, and equity, first for the Crimean war soldiers and later for the poor of London. Her 3 years of clinical practice gave her clinical expertise and credibility to assume the role of policymaker. She embraced that role because of her high degree of internal distress and concern about needless suffering and premature death of her patients (McDonald, 2006). Empowered by her clinical practice during the Crimean war, she used data that she had collected systematically to persuade Parliament to make needed military and civic law reforms that promoted health. In 1858, Nightingale became the first woman elected as a member of the Royal Statistical Society and later became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association (Gill & Gill, 2005). Her work and prestige were Victorian era validations of the importance of using evidence to inform policy. Nightingale’s activism presaged the APN as patient advocate and policy shaper. She leveraged statistics and clinical expertise to become an effective advocate for influencing policy. She expected nurses to have a high degree of social interest and to be involved in the policymaking process. All policy involves decisions that influence the daily life of citizens. Longest (2010) has defined health policy as the authoritative decisions pertaining to health or health care, made in the legislative, executive, or judicial branches of government, that are intended to direct or influence the actions, behaviors, or decisions of citizens. Politics is the process used to influence those who are making health policy. Politics introduces nonrational, divisive, and self-interested approaches to policymaking, often along ideological lines. Any political maneuvering to enhance one’s power or status within a group may be described as politics. Politics is largely associated with a struggle for ascendancy among groups having different priorities and power relationships. Preferences and interests of stakeholders and political bargaining (favor swapping) are important and extremely influential political factors that overlie the policymaking process. The self-interest paradigm suggests that human motives are not any different in political arenas than they are in the private marketplace. This behavioral assumption implies that it is rational for people and organizations to use the power of government to achieve what they cannot accomplish on their own. Ideally, elected officials seek office to serve the public interest, not their own. However, to be successful in the electoral process, they need electoral support through financial contributions, rendering them beholden to fundraising and funders (Feldstein, 2006). Highly politicized decisions may often create outcomes that have little to do with efficient use of scarce resources and what is best for the general public. These forces, which may or may not be based on evidence, contribute to the lack of coordination among health policies in the United States, making policy formulation highly complex and exceedingly interesting. APN’s must engage in the political process to influence public policy and resource allocation decisions within political, economic, and social systems and institutions. APN political advocacy facilitates civic engagement and collective action, which may be motivated by patient-centered moral or ethical principles or simply to protect what has already been allocated. Advocacy can include many activities undertaken by a person or organization, such as media campaigns, public speaking, commissioning and publishing policy-relevant research or polls, and filing an amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs. Lobbying as a political advocacy tool is only effective if a relationship between the lobbyist and legislator influences or shapes a policy issue. Social media for political advocacy is playing an increasingly significant role in modern politics (Non-Profit Action, 2012). In a review of published literature, Docteur and Berenson (2009) tried to determine how the quality of U.S. health care compares internationally. Compared with other developed nations, life expectancy is shorter and rates of death from treatable conditions such as asthma and diabetes are higher in the United States. Their findings suggested no support for the oft-repeated claim that U.S. health care is the best in the world. The United States does relatively well in some areas, including cancer care, and less well in others, including chronic conditions amenable to prevention and coordinated management. The United States ranks below other nations in patient safety. The authors concluded that health reform is needed and will not diminish the areas of health care that are excellent (Docteur & Berenson, 2009). Exemplar 22-1 depicts the experience of nurse practitioners (NPs) who practice across the boundaries of two countries’ health care systems, Canada and the United States. Longest (2010) has conceptualized policymaking as an interdependent process. The Longest model defines a policy formulation phase, implementation phase, and a modification phase (Fig. 22-1). This has immense usefulness for nursing because it illustrates the incremental and cyclical nature of policymaking, two of the most important features of the U.S. health care policymaking process. Essentially, all health care policy decisions are subject to modification because policymaking in the United States involves making decisions that are revisited when circumstances shift. Our system is not designed for big bold reform. Rather, it considers intended or unintended consequences of existing policy and tweaks changes (Longest, 2010). The Constitution unambiguously gives the federal government absolute power to preempt state laws when it chooses to do so. However, the states are also granted unfettered authority, such as regulation of health care professionals and health insurance plans (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2012). Ambiguity between state and federal authority allows states to experiment with policy solutions. The “states as learning laboratory” concept has grown out of local health policy problems and enables states to experiment with innovative policy solutions that could not be done on a national level. Moreover, states have local health care problems, requiring local, flexible, and humane solutions. Many federal health policy decisions are devolving decision making to the states, as evidenced by the increase in block grants (a large sum of money granted by the federal government to a state, with only general provisions as to the way it is to be spent, contrasted with a categoric grant, which has stricter and more specific provisions) and Medicaid waivers. Because much of health care is experienced at the local level, APNs must be aware of the overlapping state and federal spheres of government and the tension between their authorities. Agenda setting is a major component of the Longest policy formulation phase. With so many health policy problems in this country, why do some problems get attention and others languish at the bottom of the policy agenda for decades? Kingdon (1995) conceptualized an open policy window, with three conditions streaming through the open window at once. First, the problem must come to the attention of the policymaker; second, it must have a menu of possible policy solutions that have the potential actually to solve the problem; and third, it must have the right political circumstances. If all three of these conditions occur simultaneously, the policy window opens and progress can be made on the issue (Fig. 22-2). Conversely, once shut, this policy window (opportunity) may never open again. Policy problems come to the attention of policymakers in a number of ways, including constituents, litigation, research findings, market forces, fiscal environment, crisis, special interest groups, and the media, singly or collectively. Wakefield (2008) has identified policy dynamics particular to agenda setting (Table 22-1). Additional dynamics have been added and each dynamic has one or more so-called accelerators, which drives the agenda setting or triggers policymakers to take action on an issue. The political circumstances that push problems onto the agenda must have a high degree of public importance and low degree of stakeholder conflict surrounding the policy solution. If there is a great deal of stakeholder disagreement, there may be competing proposals put forth, weakening the likelihood that the problem will be addressed. Strong health services research can provide the evidence base to help policymakers specify and therefore accelerate agenda setting (Longest, 2010). Policy Dynamics Influence on Agenda Setting Adapted from Wakefield, M. K. (2008). Government response: Legislation. In Milstead, J. (Ed.), Health policy and politics: A nurse’s guide. (pp. 65–88; 3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett. The budget process begins with the President’s State of the Union Address (before the first Monday in February) to highlight the Executive Branch’s spending priorities for the upcoming fiscal year. The President’s budget guides the activities of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) staff, appointed by the President to do the following: create the budget; communicate to Congress the President’s overall federal fiscal priorities; and propose specific spending recommendations for individual federal programs. The President’s budget is merely a suggestion until acted on by Congress. In February and March of each year, the House and Senate budget committees hold hearings on the proposed budget and these joint conference committees hammer out differences. On April 15, Congress passes a House-Senate budget resolution and no other spending bill can be considered until the budget resolution is adopted. Finally, the House and Senate appropriates or subdivides their allocations among the 13 appropriations subcommittees that have jurisdiction over specific spending legislation. If the appropriations process is not completed by October 1, Congress must adopt a continuing resolution to provide stop-gap funding (Congressional Research Service, 2011). Figure 22-3 illustrates a linear process for federal legislation; however, it is more of a choreographed effort than a stepwise process. Only when each step in the process is completed can legislation be passed. Therefore, very few legislative proposals introduced are ever enacted. For example, in the 110th Congress, 14,000 pieces of legislation were introduced and 449 became law (a 3.3% passage rate). Of those 449 laws passed, 144 (32%) were purely ceremonial, such as naming post offices (Singer, 2008). Counting the number of bills dropped or passed in Congress is not an accurate measure of its productivity because it does not consider the impact that the bill has on the larger society. Omnibus bills are on the rise, which role dozens of bills into a single packaged bill, making the total number smaller, but the legislation more ambitious. FIG 22-3 The path of federal legislation. H.R.1, House of Representatives introduced; S.1, Senate introduced. Any member of Congress can introduce legislation, which is assigned a number and posted (Box 22-1). The legislation gets referred to the committee of jurisdiction, referred to more than one committee, or split so that parts are sent to different committees. There are over 200 Congressional committees and subcommittees, which are functionally structured to gather information, compare and evaluate highly specific legislative alternatives, identify policy problems and propose solutions, select, determine, and report measures for full chamber consideration, provide oversight to the executive branch, and investigate allegations of wrongdoing. Committee membership enables members of Congress to develop in-depth knowledge of the matters under their jurisdiction. There are more than 13 committees and subcommittees with jurisdiction over health care. In 1885, Woodrow Wilson said, “Congress in its committee rooms is Congress at work,” which still rings true today (Wilson, 1913).

Health Policy Issues in Changing Environments

Policy Process

Policy: Historic Core Function in Nursing

Overview of the Health Policy Process: Politics Versus Policy

Health Policy

Politics

United States Differs from the International Community

Policy Frameworks and Key Concepts

Longest Model

Federalism

The Kingdon Model

![]() TABLE 22-1

TABLE 22-1

Dynamic

Activator

Examples

Constituents

The constituent can have enormous impact on agenda setting. When members of Congress learn from their constituents about deeply moving tragedies that could have been prevented or lessened, the member is moved to introduce legislation.

An automobile accident in a remote area killed three members of a family and seriously injured two. A senator knew the family, which prompted introduction of the Wakefield Act, designed to improve pediatric emergency response in rural areas and honor the family. It became public law, the Wakefield Emergency Medical Services for Children.

Litigation

Court decisions play an increasingly prominent role in setting health policy.

Stringent control of tobacco products stems from a long history of 46 states suing the tobacco industry for tobacco-related health care costs. The courts decide that certain tobacco marketing practices must stop and that tobacco companies must pay the states, in perpetuity, to compensate them for some of the medical costs of caring for persons on Medicaid with smoking-related illnesses. The first 25 years will total payments of $206 billion.

Research findings

Research on care transitions and coordination by nurses reduces hospitalizations and emergency room use and greatly reduces costs.

The IOM report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change. Advancing Health, provides a compelling evidence base to strengthen the nation’s nursing workforce (IOM, 2011).

Elements of managing care transitions are embedded in the PPACA (HHS, 2011a) by way of ACOs, in which the delivery system takes full responsibility for the care of patients as they transition home and to other care settings. The PPACA’s many provisions to expand access, reduce cost, and improve quality of care can only be accomplished by the inclusion and expansion of APNs. This will accelerate removing state and federal barriers to APN practice so that new innovation delivery models can be developed.

Market forces

The fractured health care delivery system creates opportunities for highly profitable businesses.

The CEOs of insurance companies earn enormous salaries. The PPACA includes the “Medical Loss Ratio” provision, in which insurers must spend 85% of premiums dollars on direct health care. The other 15% can go to marketing and salaries, greatly capping the multimillion dollar CEO salaries.

Fiscal environment

Very different budget decisions are made when the government is addressing deficit rather than surplus spending. Deficit spending restricts budgets to a pay as you go policy

Deficit financing forces budgetary restrictions in fiscal year 2013. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention budget gets a $600 million cut during a deficit crisis. Many other health programs get budget cuts or receive level funding.

Special interest groups

Well-organized special interest groups with a clear message can have an enormous impact on government action or inaction.

The autism advocacy community frames the increase in autism spectrum disorders as a public health emergency, motivating Congress to pass legislation spanning a wide range of provisions for those with autism, including research, treatment and services (www.autismvotes.org).

Crises

Crises can promote rapid response policy changes, usually centered on quality and access.

World Trade Center first responders in New York endure debilitating diseases, sickened from the toxic dust. A program is passed into law to provide federal reparatory and remedial compensation; $300 million is proposed.

Political ideology

The majority party (Democrats versus Republicans) has a large impact on agenda setting. The divide centers on what role the government should play in U.S. society.

The newly installed 112th Republican-controlled House of Representatives introduced the second bill of the session in January 2011, the Repealing the Job-Killing Health Care Law Act, a failed attempt to repeal the PPACA.

Media

The lay press, reporting on policy issues or crises, often compel policymakers to take action.

Major news outlet reported that millions of unencrypted personal health care records were stolen or mistakenly made public. Tensions rise between added reporting requirements and privacy. Legislation is introduced on strategies to enforce the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and mandate encryption.

U.S. president with a high degree of commitment

When the occupant of the White House sets health reform as a major domestic policy agenda by linking unsustainable health care costs to the health of the macroeconomy, the power of that office becomes evident.

In March 2010, President Obama signs the historic PPACA, despite a 2-year debate, town hall meetings across the nation, and multiple national speeches explaining to the public why reform is necessary.

Federal Budget Cycle

Budget Cycle

Policy Formulation: How a Bill Becomes Law

Congressional Committees

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Health Policy Issues in Changing Environments

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access