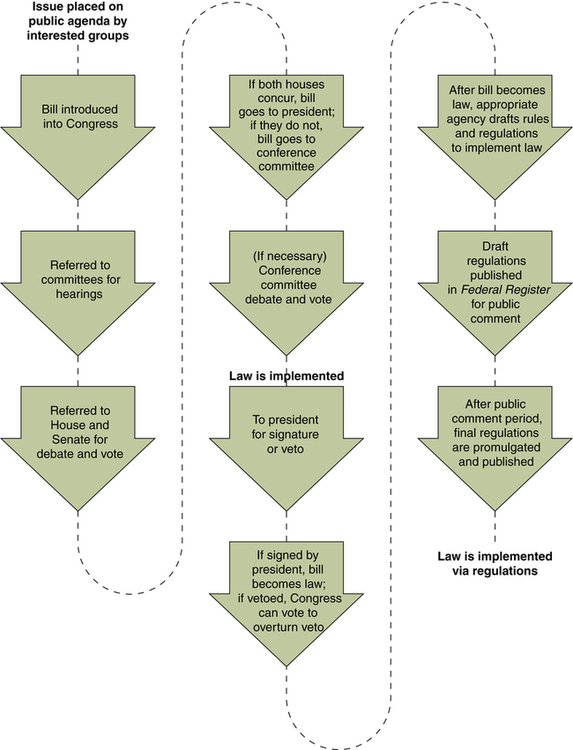

Debra C. Wallace, PhD, RN and L. Louise Ivanov, DNS, RN At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify political, legislative, social, and economic factors affecting health policy and nursing. • Describe the legislative, budgetary, and regulatory processes for developing, implementing, and evaluating policy. • Discuss selected health programs mandated by federal health policy. • Evaluate health policies for their impact on nursing practice, education, research, and the practice environment. • Discuss strategies for nurse participation in health policy. Nurses are members of many organizations involved in and influencing the development of health policy and health care–related legislation. Nonlegislative citizens also play a political role in health policy development and implementation through participation in and support of civic organizations and activities, such as the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), American Diabetes Association (ADA), the March of Dimes, the National Organization of Women (NOW), and the National Rifle Association (NRA). Most professional organizations (e.g., American Medical Association [AMA], American Hospital Association [AHA], American Academy of Nursing [AAN], Coalition for Patients’ Rights [CPR]) develop legislative agendas, support political candidates, and employ lobbyists at state and federal levels. (See Box 6-1 for a list of government and health care organizations referred to in this chapter.) In 2004, the ANA moved its headquarters from Kansas City to Washington, D.C., to increase visibility and access to federal agencies and Congress. State nursing associations often have lobbyists to ensure state laws for advanced practice licensure, Medicaid benefits and coverage, and work environment protections. Lay, civic, and professional organizations, whether or not associated with a political party—such as the AARP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP), the NRA, the ANA, the National Home Care Association (NHCA), and the America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP)—use grassroots activity, paid lobbyists, campaign support, advertisements, and organized rallies to make an impact on health policies affecting their members and special interest groups. Most health care professional organizations, including the ANA, have a paid lobbyist in each state capital and at least one in Washington, D.C. Because these organizations fund political and lobbying activity, a proportion of membership dues to these organizations are not tax deductible. For example, the ANA uses approximately 25% of its dues for lobbying activities and has a full-time lobbyist in Washington. Many state nursing associations have their own lobbyist or contract for this work in their state legislature. A major concern over the past two decades has been the influence of money on campaigns, resulting in increased access to legislators and greater influence on legislation by PACs and financial contributors. The Federal Elections Commission (FEC) regulates the type, amount, and reporting of such funds. State commissions handle funds within state, county, and municipal governments. Each candidate, political party, and PAC is required to register and submit quarterly, monthly, or annual financial reports. This is traditionally referred to as “hard money.” “Soft money” is less regulated and refers to funds given to the party but for no specific purpose. Soft money is often used to support campaign activities but under a different guise. For example, instead of giving money to a senatorial campaign for travel to a state capital, the party supports a high school student workshop on a topic that invokes the candidate’s position, thus averting the campaign finance rules constraining usage. Campaign finance reports, as well as documentation of PACs, corporate, and other large contributors to each party and candidate, are required by the FEC and are available to the public (see www.fec.gov). Monies spent on media, travel, and food by campaigns have increased tremendously in the past decade. Many of the organizations noted above—as well as many nurses, doctors, physical therapists, and patients—donated to these campaigns. In federal campaigns in 2007 and 2008, individual contributions were limited to $2300 per candidate and $28,500 per national party, or a total of $42,700 to all candidates combined and $65,500 to all PACs or committees combined. In contrast, national, state, or local party committee contributions were limited to $5000 per candidate per election, unlimited to political parties yearly, and limited to a maximum of $39,900 to a U.S. Senate candidate per campaign (FEC, 2009a). However, in January 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that campaign contribution limits were an unconstitutional denial of free speech. It is unclear what effect this will have on future campaign financing. Many state political contribution limits are similar to national levels or are based on population and candidate numbers each election cycle. In addition to funds raised by candidates, the government provides funds from the taxpayer-supported Presidential Election Campaign Fund (PECF). These monies are designated on federal income tax forms and then distributed to candidates after they raise a specified amount. A cap of $40 million is placed on what can be spent on primaries or preconvention efforts for presidential candidates who choose to accept these funds. In 2008, $103 million in federal funds were used in the presidential primaries and campaign. President (then Senator) Obama chose not to accept federal dollars; Senator McCain “opted in” to the system and received 84 million federal taxpayer dollars (FEC, 2009b). As was true in 2004, both candidates benefited greatly from the amounts the parties or PACS spent on advertisements and other media to support them. Before the 2000 election, the FEC reported that eight candidates for the presidency had raised a total of $181 million (FEC, 2000). In the 2004 election, presidential candidates Kerry and Bush both raised more than $298 million for their respective campaigns, and more than $1 billion was used by parties, candidates, and federal funds combined (FEC, 2005). Similarly, McCain, Obama, their rivals, and political parties raised more than $1.67 billion for the presidential primaries and campaign for the 2008 election (FEC, 2009b). This is more than the initial year of spending for the Medicare Prescription Drug Plan (PDP). Two new modes of funding appeared in the 2004 presidential campaign. Howard Dean, MD, was the first candidate to formally use the Internet to solicit and receive contributions. Second, a new type of committee called 527 political groups arose and altered political fundraising and campaign activities. These groups can engage in voter mobilization efforts, issue advocacy, and other activity short of expressly advocating the election or defeat of a federal candidate. There are no limits to how much they can raise. These organizations are regulated by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), but not necessarily the FEC if they do not explicitly advocate for an individual’s election or defeat or do not directly subsidize federal elections. Thus this is a major loophole to raising and using soft money. In the 2004 campaign, these entities ran oppositional, and personal, attacks on candidates. Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, Progress for America, MoveON.org, and Voices for Working Families are just a few of the organizations that provided significant media coverage and had a considerable impact on the election. In 2008, these organizations ran advertisements that showed candidates’ positions in a very demonstrative and stark manner. For example, John Kerry was portrayed as unpatriotic even though he volunteered and served in Vietnam. George W. Bush was portrayed as supporting child labor because of the large deficits, even though child labor laws were not changed during his term. An important process to understand is illustrated in How Our Laws Are Made (U.S. House of Representatives, 2003; U.S. Senate, 2003), which explains how a bill proceeds through the U.S. Congress. Steps, processes, facilitators, and barriers to enacting legislation at the federal level from introduction of a bill through its enrollment to the president are detailed (Figure 6-1). This illustration also identifies the House and Senate procedures, including leadership roles and responsibilities, committee assignment, readings on the chamber floor, and resolution between the two chambers. Many of the steps and processes, such as the House “hopper” and the system of bells and lights, originated in the late 19th century. The hopper is the box in which representatives initially place a piece of legislation they wish to be brought to the House for action. A system of bells and lights is in place throughout the Capitol building to notify senators and representatives of pending votes and other actions. Also discussed in this document is how to “bury” or “kill” a bill and how the majority party ideas prevail even in the most sacred workings of our democracy. Many state legislations follow similar protocols and procedures. It is incumbent upon nurses to know the major committees and legislators that deal with health and nursing issues in their own state, as well as the major pitfalls or bridges where nurse and health-focused legislation may be delayed or strengthened. The state nursing association can assist with identifying those persons, committees, barriers, and facilitators. A majority of the budget for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) is for entitlement programs, which means that only a third or less of the amount appropriated by Congress for this department can be controlled or used in discretionary ways. The NIH, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Bureau of Health Professions (BHP) are included in the USDHHS budget. Nursing leaders and others have continually worked to increase these budgets, and these efforts resulted in budget increases during the late 1990s and early 2000s. More recently, those appropriations have been more stagnated. In calendar year 2008, CMS expenditures totaled more than $556.7 billion, with federal Medicaid obligations totaling $267 billion and federal Medicare obligations totaling $283 billion (CMS, 2008). The NIH fiscal year 2008 budget was $27.8 billion, and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) budget was $134.7 million (NIH, 2008). Overall health care spending grew 6.1% from 2006 to 2007, averaging $7421 per person. The health care portion of the gross domestic product (GDP) increased from 16% to 16.2% (Hartman et al., 2009) This is the slowest growth in 10 years, but hospital care still provided for a third of all expenditures. Various agency heads make budget requests to congressional committees each year through letters, hearings, and routine budgetary processes. In 1999, a federal surplus of $170 billion resulted from a thriving economy, a leaner governmental structure, and the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. However, Congress has been borrowing from the Social Security Trust Fund since the early 1980s to meet annual operating costs and appropriations across the government. The retirement income and Medicare programs that are funded by current worker payroll taxes do not contain enough money to fund those same workers when they reach 65 years of age. The General Accounting Office (GAO) estimates that the Social Security (SS) Trust Fund will be unable to meet its obligations starting in the year 2040. Debate continues over how a government with a large national debt and a large tax base can best serve its citizens, given the promises made to citizens regarding retirement and health insurance in old age. In 2005, major efforts were proposed to change SS through decreased benefits to younger workers, initiation of private health savings accounts, gradually increasing the salary cap for paying SS taxes, and a means-tested eligibility for full benefits. Some of these passed, but not much change resulted for the long-term commitment of the fund. The financial crisis of 2008 may require the 111th Congress to revise both SS retirement income and Medicare. State legislators also must deal with budget shortfalls and use hiring freezes, layoffs, program cuts, new fees, and increased taxes to meet needs. Local agencies and school boards are often the most successful in dealing with budget shortfalls because they have not had—or have not chosen to use—the ability to borrow funds, incur long-term debt, or move costs from one budget year to another. More detail on the budget and health care costs can be found in Chapter 7. The USDHHS is charged with protecting and ensuring the health of the nation and is headed by the Secretary of Health. Multiple agencies and divisions are included in the USDHHS, and several assistant secretaries are responsible for administrative aspects. The Surgeon General (SG) is an Assistant Secretary of Health and heads the Office of Public Health and Science (OPHS). An Assistant Secretary for Aging heads the Administration on Aging (AOA) and the Administration for Children and Families (ACF). Other agencies are headed by a commissioner (e.g., FDA) or director (e.g., NIH). Agencies include several sections or divisions. For example, the NIH has 27 institutes or centers, including the NINR, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). In Atlanta and other regional offices, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) houses 14 centers, institutes, and offices, including the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), the National Office of Public Health Genomics (NOPHG), the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), and the Coordinating Office for Terrorism Preparedness and Emergency Response (COTPER) (CDC, 2009). Most federal government agencies and state agencies have civil rights, legal, public relations, and budget sections staffed by career employees. These agencies have public Internet sites for consumers and professionals to obtain program and contact information. Many political, professional, and health-related agencies and organizations also house websites for rapid and wide public access and dissemination of information.

Health Policy and Planning and the Nursing Practice Environment

![]() Politics

Politics

ORGANIZATIONS

FINANCING

![]() Understanding the Legislative Process

Understanding the Legislative Process

![]() Budget Process

Budget Process

APPROPRIATION OF FUNDS

ECONOMICS

![]() Health Programs

Health Programs

IMPLEMENTATION AND REGULATION

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access