CHAPTER 24 Health managers in a changing system

When you finish this chapter you should be able to:

Managers, management and organisations

A third important element is that management is done in the context of a company or organisation or team. Authority is part of the job — the manager’s mandate to control the work of others is included in the job description and often drawn in an organisation chart. It is the organisation that defines the authority of the managers, and sets the limits of their authority, sometimes called delegation. For example, a nurse unit manager will usually have authority (or a delegation) to order supplies and equipment to a certain monetary value. Of course, the limits of authority are also given by laws and regulations of the society and the industry. For example, your boss cannot direct you to do something illegal, or something that is unsafe for you or others, or something that is not part of the manager’s responsibility as a manager. These three elements — getting things done through others, taking responsibility for their work, and doing it within an organisation — define management in the health and community services industries.

Managers and management in health care

Third, health policy is one of the most important responsibilities for governments. In practice, this means that everything health care organisations, and their managers, might want to do or change has some sort of policy or political dimension. Difficulties arise when there is a conflict between management attempts to deal with a problem, and political goals of ensuring that voters are happy with their access to, or the quality of, their health services. This is more likely to be the case in the public sector, but even private hospitals or practitioners are also influenced in their management by this kind of interaction with the political world.

Who are the managers?

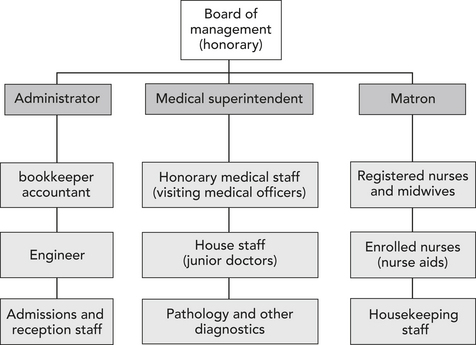

To understand the current management workforce, a little history about the role of hospital managers is useful. In Australia, the traditional management structure of a hospital (until about the 1970s) had a senior doctor (called a medical superintendent), a senior nurse and an ‘administrator’, all reporting to a board. Making this triumvirate work was a challenge for all of the senior managers, and for the board. Administrators generally had a finance background, and many were accountants. The chart in Figure 24.1 was typical of the structure of hospitals in Australia until the 1970s.

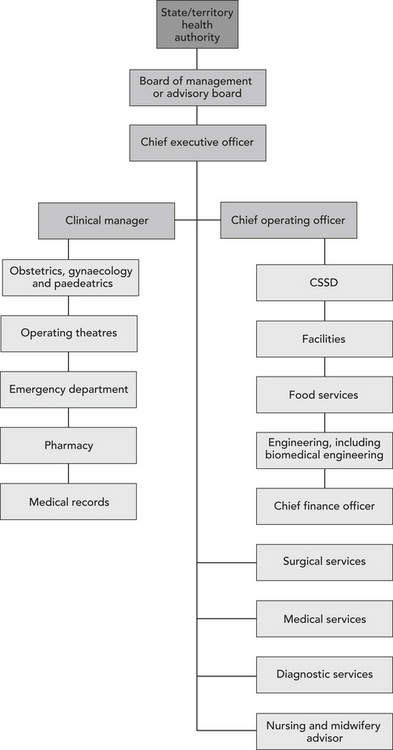

Similarly, there has been a shift in the way that staff groups are organised to deliver care, with less emphasis on single profession departments. There has been more of a focus on the importance of the multiple clinical needs of patients; for example, maternity patients will need access to midwives, sometimes obstetricians and physiotherapists, ultrasound, and so on. Those with an interest in management in all the professions and occupations have thus had some opportunities to broaden their scope, and to take on managing operating theatres or laboratories, a community health team, a division of allied health, a division of general practice or a clinical stream. Management qualifications are also well regarded for these jobs and careers. A typical large structure would now look more like that shown in Figure 24.2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection