Health Information Management Processing

Nadinia Davis

Chapter Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. List, explain, and give examples of the three types of controls.

2. Explain the flow of postdischarge processing of health information.

3. List and explain the major functions of a health information management department.

4. Explain the principles and process flow of an incomplete record system.

5. Compare and contrast paper-based versus electronic records processing.

Vocabulary

abstract

abstracting

assembly

audit trail

batch control form

coding

completeness

concurrent analysis

concurrent coding

corrective controls

countersignature

data entry

deficiencies

deficiency system (incomplete system)

delinquent

detective controls

discharge register (discharge list)

exception report (error report)

indexing

nonrepudiation loose sheets (loose reports)

postdischarge processing

preventive controls

quantitative analysis

queue

release of information (ROI)

retention

revenue cycle

root cause analysis

timeliness

universal chart order

The previous several chapters have focused on the collection of data by clinical practitioners and the organization of that data. This chapter turns attention to the postdischarge processing of patient data, some data quality control measures, and the role of the health information management (HIM) professional in ensuring data quality, information access, and record retention.

This chapter discusses paper-based processing as well as electronic records processing. Ideally, electronic records replace paper-based records in their entirety. However, it is important to note that facilities must be prepared to conduct business as usual in the event of computer system “down time,” interruptions in service that prevent use of the electronic health record (EHR). System down times can be planned, such as for system upgrades and other system maintenance. Unplanned down times, due to hardware failure, software crashes, and natural disasters, may also occur. Staff must be trained to continue to collect and record data for continuing patient care and patient safety, regardless of the availability of the electronic record. After down time, procedures must also be in place to either backload (enter later) the manually collected data or scan the paper collection into the computer.

Data Quality

Whether the data are recorded by hand or entered into an electronic record, the process of recording data into an information system is called data entry. In health care, a patient’s life can depend on the accuracy and timeliness of the data entered. For example, if an incorrect blood type were recorded and a patient then received the wrong blood type during a blood transfusion, that patient might experience a life-threatening transfusion reaction. Consequently, the overall quality of the data that are recorded is critical. The data quality characteristics of timeliness and completeness defined in Chapter 2 are reinforced here.

Timeliness

Timeliness refers to the recording of data within an appropriate time frame, preferably concurrent with its collection. Numerous regulations, both on the state licensure level and on the level of accreditation by voluntary agencies such as The Joint Commission (TJC), address the issue of when specific data must be recorded. The previous chapters discuss some of these regulations. For example, according to TJC rules, an operative report must be documented immediately after the operation (TJC, 2012). A history and physical (H&P) must be completed (dictated and present in the health record) within 24 hours of admission or before a surgical procedure (Federal Register, 2012; TJC, 2012). Timeliness applies to many other activities, as subsequent discussions demonstrate.

Timeliness is important, particularly from the health care facility’s perspective, because the patient’s health record is part of the normal business records of the facility. Therefore data that are being entered into the health record must be recorded as soon as possible after the events that the data describe. For example, if a nurse is monitoring a patient at 3:00 PM, then the note that he or she records in the patient’s record must be written very shortly thereafter. Ideally, the note is written concurrently with the observation: point-of-care charting. Writing that same note at 9:00 PM, 6 hours after the actual observation, could impair the quality of the recorded note. Can the nurse really remember, 6 hours later, exactly what happened with the patient? Can a physician really remember, weeks later, exactly what happened during an operation well enough to dictate an accurate report?

After the patient has been discharged from an acute care facility, the record must be completed within a specified period of time, usually 30 days. State licensing regulations and medical staff bylaws, rules, and regulations will define the facility’s standard for chart completion; however, the maximum is 30 days, by both TJC and Conditions of Participation (COP) standards. In the presence of conflicting standards, the most stringent takes precedence. So, if state licensing regulations require a record to be completed within 15 days of discharge, that shorter time frame takes precedence over 30-day standards. Because timeliness is so important, a significant amount of time and energy is spent facilitating the timely completion of health records.

Completeness

Completeness refers to the collection or recording of data in their entirety. For example, a recording of vital signs that is missing the time and date is incomplete. A comprehensive physical examination that omits any mention of the condition of the patient’s skin is incomplete. A progress note that is not authenticated is incomplete.

Complete data support the record of care of the patient. If a time is missing from a medication administration record, the hospital cannot provide evidence that the medication was administered on a timely basis. If the physician leaves out the condition of the patient’s skin from a physical examination, the hospital may have difficulty claiming that a decubitus ulcer was present on admission.

In order to ensure that data collection and recording are timely and complete, health care organizations, such as hospitals and other providers of health care, must develop and implement data quality controls. Table 5-1 summarizes the data quality concepts that have been discussed in this text so far.

TABLE 5-1

| Element | Description | Examples of Errors |

| Accuracy | Data are correct. | The patient’s pulse is 76 beats/min. The nurse recorded 67. That data entry was inaccurate. |

| Timeliness | Data are recorded within a predetermined period. | Operative reports not recorded immediately following surgery. |

| Completeness | Data exist in their entirety. | Date, time, or authentication missing from a record renders it incomplete. |

Controls

There are many opportunities for errors to occur. Data entry errors may occur whether handwritten or electronically entered. The primary purpose of documentation is communication. For example, the documentation communicates among caregivers for continuing patient care as well as to payers, to justify and substantiate the care provided, and to regulatory or accrediting agencies to demonstrate the quality of patient care. If an individual’s handwriting cannot be read by another health professional, how can those data elements be communicated? How can they be considered valid or accurate? If only the author of the data can decipher the writing, the data are useless to others. If a nurse records a temperature of 98.6° F without the decimal point (986° F), the temperature recorded is not valid. A physician’s order that requests 100 mg of a medication instead of 10 mg could have fatal consequences if the larger dose is actually administered.

One way that data can be protected so that they are accurate, timely, and complete is through the development and implementation of controls over the collection, recording, and reporting of the data. This chapter focuses on the collection and recording of data. There are three basic types of controls over the collection and recording of data: preventive, detective, and corrective (Table 5-2).

TABLE 5-2

| Control | Description | Example(s) |

| Preventive | Helps ensure that an error does not occur | Computer-based validity check during data entry; examination of patient identification before medication administration |

| Detective | Helps in the discovery of errors that have been made | Quantitative analysis (e.g., error report) |

| Corrective | Correction of errors that have been discovered, including investigation of the source of the error for future prevention | Incomplete record processing |

Preventive Controls

Preventive controls are designed to ensure that data errors do not occur in the first place. The best example of a preventive control is a software validity check. For example, suppose a user entered a date as July 45, 2012 (i.e., 07/45/2012). If the software is programmed to prevent one from entering invalid dates, it might send a message (an alert) saying, “You have entered an invalid date—please re-enter.” It might even make a loud sound or block the character “4” from being typed in the first position of the day field.

Preventive controls are common, both in protocols surrounding clinical care and in paper-based data entry. For example, a nurse checks the patient’s identification band before administering a medication to ensure that the medication is being given to the correct patient. In an electronic medication administration system, bar coding of both the patient wrist band and the medication itself (bar code medication administration) is a preventive control. The development of well-designed, preprinted forms to collect data also helps ensure that data collection is complete. Some facilities use a combination of paper and bar codes to collect data.

Preventive controls can be expensive and cumbersome to develop and implement. Health care providers might resist the implementation of preventive controls if they are burdensome and time consuming. Therefore the cost of a preventive control must always be balanced against its expected benefits. It is relatively easy to justify checking medications, orders, and patient identification because patient safety is of paramount concern. It is not quite as easy to justify developing a control to prevent the entry of an incorrect patient language or ethnicity.

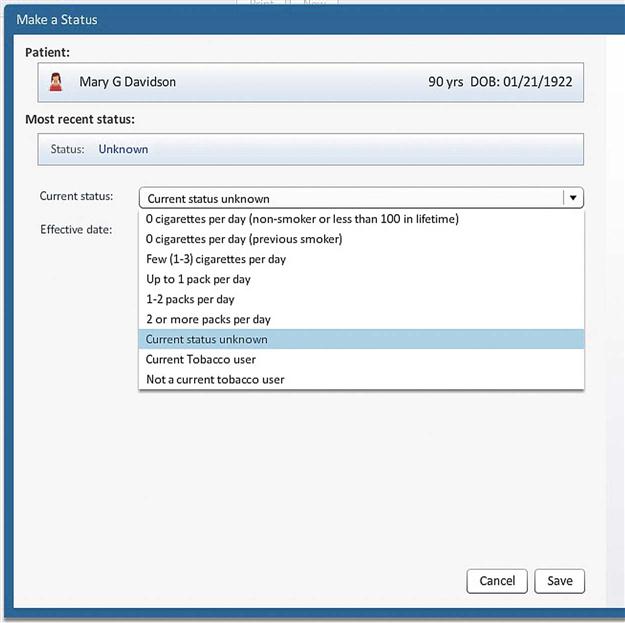

One simple way to prevent invalid data entries is with the use of multiple-choice questions on a printed form or drop-down menu in an electronic record. All of the valid choices are listed so that the recorder merely chooses the correct one for the particular patient (Figure 5-1). This method also prompts the user to complete the form. However, this method does not prevent inaccurate or untimely entries because it is still possible to hit the wrong key without realizing it. For example, the staff member may enter the wrong sex for a patient. Because the computer program has no way of “knowing” whether the patient is male or female, it does not prompt a correction. Thus comprehensive preventive controls are not always guaranteed.

Detective Controls

Detective controls are developed and implemented to ensure that errors in data are discovered. Whereas a preventive control is designed to help prevent the person recording the data from making the mistake in the first place, a detective control is in place to find the data error after it is entered. In the previous date example (7/45/2012), a detective control might generate a list of entries that the software recognizes as problematic. Such a printout is called an error report or exception report. Error reports are also generated when the computer or other system encounters a problem with its normal processing. For example, a pharmacy system can be programmed to print an error report to alert the pharmacist that a medication order exceeds the normal dose. Omissions may also be highlighted in an error or exception report. For example, if the medication was ordered but not recorded as administered, this mistake could be detected on an exception report.

Detective controls are critical in a paper-based environment. Because there is no practical way to completely prevent erroneous data entry in a paper-based environment, the process of searching for errors is necessary. For example, nursing medication records may be reviewed regularly to ensure that medication administration notes are properly entered. Also, if a physician fails to dictate an operative report in a timely manner, a control must be in place to detect the missing report.

Detective controls are frequently the easiest and most cost-effective method to develop and implement, but as with preventive controls, they may be complex. The development of preventive and detective controls requires a thorough knowledge of the process being controlled as well as the potential negative impact of data errors in processing. For this reason a particular detective control may be performed either facility-wide, under the review of an overall quality improvement plan, or by a specific department.

Corrective Controls

Corrective controls may be developed and implemented to fix an error once it has been detected. Corrective controls follow detective controls. In general, identifying an error wastes time and is ineffective if the facility does not correct the mistake. However, corrective controls, by their design, occur after the error has occurred. Thus if an error report identified an invalid date, such as July 45, the date would be corrected after the fact.

Nevertheless, some errors cannot be effectively corrected once they occur. In such cases, investigation of the error is necessary to determine whether sufficient controls are in place to prevent the error in the future. This is an important component of a process improvement or quality improvement program. For example, if a patient received an injection of an incorrect medication, the medication cannot subsequently be withdrawn. However, the events leading up to the administration of the drug can be thoroughly examined to determine why the error occurred. Did the physician order the wrong medication? Was the order transmitted incorrectly to the pharmacy? Did the health care provider check the patient’s wristband before administering the medication? Once the source of the error is determined, the appropriate correction to the process can take place.

The process of determining the cause of an error is often referred to as a root cause analysis, or RCA. Facilities in which serious medical errors take place, such as an error that alters a patient’s quality of life or results in death, may be required to report these errors with an RCA and a corrective action plan to the appropriate regulatory agencies. Employee education and disciplinary action are two examples of typical corrective actions that may take place if procedures were in place but not followed. Health care professionals, such as nurses and physicians, can lose their professional licenses if serious patient errors occur once or continue to occur even after the corrective action plan is in effect.

The HIM department plays a role in the detection and correction of certain documentation errors. Earlier in the chapter, an unsigned progress note was used as an example of incomplete data. In a paper-based environment, the HIM professional would have to obtain the record and read all of the progress notes in it to identify the incomplete note. In an electronic record environment, preventive control alerts, such as noises and verbal prompts, can be built into the program to encourage the authentication of the note at the time the note is originally recorded and also on subsequent access to the record. As a detective control, an exception report can identify incomplete notes. In both paper-based and electronic record environments, the corrective control consists of alerting the physician to the omission and giving him or her the opportunity to complete the note.

Correction of Errors

The correction of errors is an important consideration in patient record keeping because nothing that is recorded should be deleted. Corrections must be made so that the error can be seen as clearly as the modified information. In a paper-based record, errors are corrected by drawing a line through the erroneous data and writing the correct data near it. It is important not to obscure the original entry because doing so may lead to the perception that someone attempted to cover up a mistake. The correction must be dated, timed, and authenticated. In addition, correction of errors cannot consist of destroying entire documents or pages of a record. All of the erroneous documents or pages must be clearly labeled as incorrect, authenticated, timed and dated, and kept with the correct portions of the record.

In electronic records, errors can be corrected in several ways depending on the type of error and the data that are being changed. For example, suppose that a patient admitted to a facility had been treated there before. A record of the previous visit exists. The patient registration specialist looks at the previous record and discovers that the patient has moved. The address and telephone number are now incorrect. Therefore the patient registration clerk may delete the old data and replace it in the patient’s record with the new data. In doing so, the software should be programmed to create a historical file of the patient’s previous addresses. On the other hand, a physician making a correction to a progress note must create an addendum to the record, identifying the error and entering the new note. In both cases, an audit trail should be created to indicate that the correction was made (Figure 5-2).

An audit trail is a list of all activities performed in a computer, including changes to the patient’s record as well as viewings of the record. In addition to the date and time, medical record number (MR#), and patient account number, the audit trail contains a list of the activities, the workstation at which the activity took place, the user who performed the activity, and a description of the activity itself. In the case of changes, the audit trail also may be programmed to contain the precorrection and postcorrection data. Because the audit trail indicates the user, it can be used to determine whether errors are being made by certain staff members so that retraining can target the correct individuals. An audit trail may be generated automatically to review specific data elements, such as changing a patient’s status from outpatient to inpatient. Other audit trails are designed to be generated on demand: for example, to review records for inappropriate access.

Postdischarge Processing

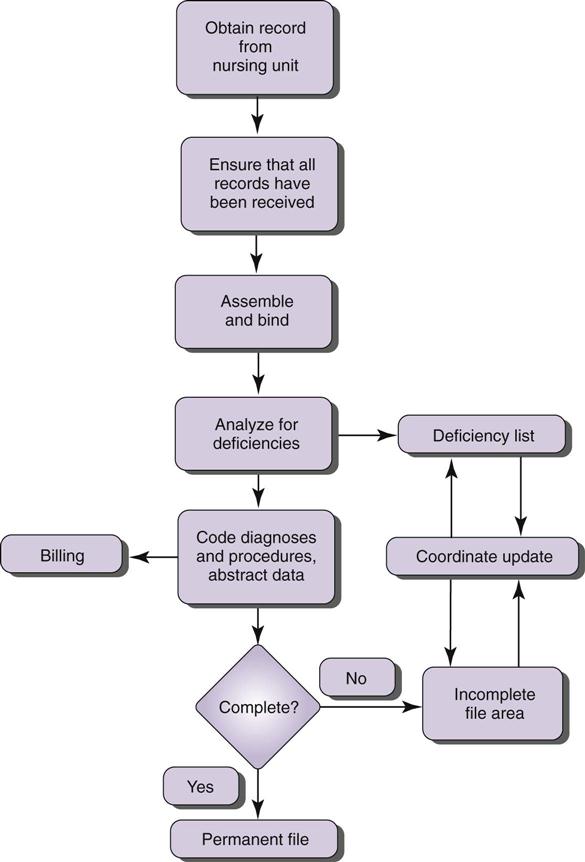

The understanding of data concepts and control issues is critical for the development and implementation of postdischarge processing procedures (Figure 5-3). Postdischarge processing is what happens to a patient’s record after the patient is discharged. In a paper-based environment, postdischarge processing is a series of procedures aimed at retention, or storage, of an accurate and complete record. In an electronic record environment, the record is already stored in the system; therefore postdischarge processing consists of ensuring that the record is accurate and complete before being archived. With a hybrid record, both paper record and electronic record procedures may be necessary.

Key concepts to understand in the retention of records include the following:

Retention: Storing the record appropriately and for the necessary amount of time

Security: Preventing accidental destruction or inappropriate viewing or use of records

Access: Ensuring that the record is available timely should it be needed

Table 5-3 summarizes the components of record retention. Members of the HIM department and facility staff must adhere to requirements for record retention. These requirements vary from state to state.

TABLE 5-3

COMPONENTS OF RECORD RETENTION

| Component | Description |

| Storage | Compiling, indexing, or cataloging, and maintaining a physical or electronic location for data (see Chapter 9) |

| Security | Safety and confidentiality of data (see Chapters 9 and 12) |

| Access | Ability to retrieve data; release of data only to appropriate individuals or other entities (see Chapters 9 and 12) |

Postdischarge processing is traditionally performed by the facility’s HIM department. In a small physician’s office or long-term care (LTC) facility, the entire process may be performed by one person. In a group practice or small inpatient facility, the process may be divided into functions and distributed among several individuals. In a large facility, many individuals may perform each of the separate functions of the process. The data concepts and control issues are relevant to many other health information environments. The following descriptions pertain to inpatient facilities. Although the principles are the same when applied to outpatient facilities, the application of the principles may vary.

Identification of Records to Process

Postdischarge processing begins with the identification of discharged patients: what records need to be processed. This can be accomplished by reviewing a list of the patients who have been discharged: the discharge register or discharge list. As patients are discharged from the facility, their status is updated in the computer system. The discharge date and time are entered. This data entry may be performed by nursing or registration staff because they are the individuals most likely to know exactly when the patient has left. Bed control is notified, either manually or electronically, that the patient’s bed is unoccupied. Housekeeping is notified that the room needs to be cleaned. All three tasks (discharge, notification, and cleaning) must take place in order to admit another patient to that bed. If the patient leaves but the discharge date is not recorded and bed control not notified, the number of patients in the facility (census) is incorrect and the discharge list is missing a patient. This detailed understanding of the discharge process and how it is performed in one’s facility enables users of the discharge register to detect and correct errors. For example, if a record is received but the patient is not on the discharge register, the HIM department must determine what error has been made and notify the correct area to fix the problem.

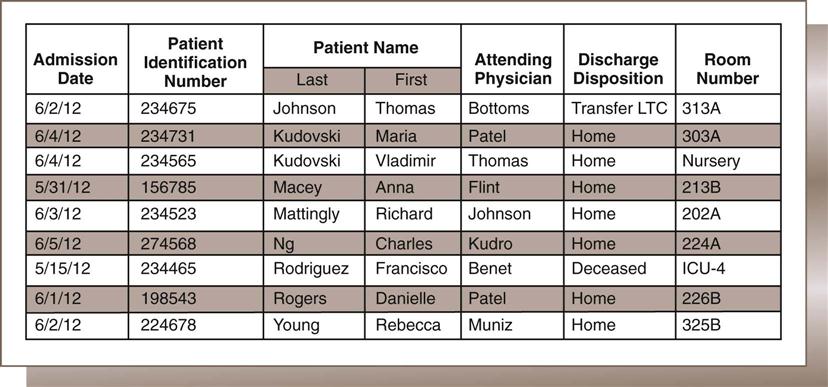

A corrective control in this process may involve someone physically visiting all nursing units around midnight, essentially doing a bed check to verify whether all discharges have been recorded and that the census correctly identifies all of the patients and their locations. Nursing may perform this check comparing the patients in the beds with a computer printout of all inpatients. In paper-based facilities, the discharge would be a manual entry into a register, which could be photocopied or manually copied to a list for distribution to departments that use the discharge register, such as HIM. Manual census and discharge registers in a hospital are rare because the MPI has been computerized for decades. In a computer-based facility, flagging the patient status and entering the discharge date and time are performed through computer data entry. The discharge register is then a printed report of all patients discharged on a specific day or during a specified period. However it is compiled, the discharge register contains a list of the patients who have been discharged on a specific calendar day. A day is from 12:01 AM to 12 midnight, so discharges may include a patient who died at 11 PM and one who left against medical advice (AMA) at 5 PM. Figure 5-4 illustrates a discharge register.

In a paper-based acute care environment, patient records move from the point of care, or patient unit, to the HIM department after discharge. Once the patient has been discharged, documentation should be nearly complete and could theoretically be moved to the HIM department immediately upon discharge. Because the patient has already left the facility, the record is no longer needed for direct patient care. Usually, however, records remain on the patient unit until the morning of the day after discharge. This practice gives the physicians, who are not necessarily at the facility all day, time to sign off on orders and perhaps dictate the discharge summary. It also gives nursing and other clinicians time to complete their documentation.

The process by which paper records move from the patient care unit to the HIM department varies by facility. Some of the considerations that determine what process is used include the distance from the patient units to the HIM department, the staffing levels on the patient unit, the staffing levels in the HIM department, and the availability of alternative personnel, such as volunteers. An example of a common practice is as follows: Patient unit personnel remove the records from their binders and leave them in a pile for pickup; the records are then picked up by any authorized person and delivered to the HIM department. Alternatively, the patient unit personnel may deliver the records. Some facilities use physical transportation systems such as pneumatic tube systems, elevators, and even transport robots.

The cost of moving paper records from one place to another is also a consideration. The cost is measured by the amount of time it takes to obtain the records times the hourly wage of the person performing the task. If it takes  hours for an HIM clerk to obtain the records daily and that clerk earns $12 per hour, then it costs $18 per day (

hours for an HIM clerk to obtain the records daily and that clerk earns $12 per hour, then it costs $18 per day ( × 12) to pick up the records. However, it may take 6 unit clerks 5 minutes each (30 minutes per day) to drop off the records on their way to the time clock at shift change. If the unit personnel can drop off the records at shift change, the cost may be reduced to $6 per day—assuming that the unit personnel also earn $12 per hour. Thus the hospital could save 1 hour of staff time ($12) per day by making this process change. That is an annual savings of $4380 (365 days × $12/day).

× 12) to pick up the records. However, it may take 6 unit clerks 5 minutes each (30 minutes per day) to drop off the records on their way to the time clock at shift change. If the unit personnel can drop off the records at shift change, the cost may be reduced to $6 per day—assuming that the unit personnel also earn $12 per hour. Thus the hospital could save 1 hour of staff time ($12) per day by making this process change. That is an annual savings of $4380 (365 days × $12/day).

Once the record arrives in the HIM department, postdischarge processing can begin. The first step is to ensure that all records have been received. This can be accomplished by checking the records received against the discharge register. If a patient was discharged but a record was not received, the patient unit staff should be contacted immediately so HIM can obtain the record. If a record was received but the patient is not listed on the discharge register, the record may have been sent in error (e.g., the patient may not actually have been discharged). Alternatively, the discharge register may be incorrect (e.g., the patient was discharged but not added to the discharge register). The patient unit staff should be contacted to verify the patient’s status, and whatever error was made should be corrected immediately.

Other departments also rely on the accuracy of the discharge register. Members of the nutritional or dietary department would not want to deliver meals to patients who are no longer at the facility. The nursing department must know the exact bed occupancy statistics for every unit to ensure appropriate staffing levels. The admitting department must know which beds are open for new admissions. Therefore the facility must have a procedure in place, whether telephone, facsimile (fax), Internet communication, or computer-based system, to systematically notify the relevant departments. In an entirely electronic system, notifications among departments would be unnecessary, if the new status automatically “populates” into the department modules as the patient’s status changed.

Assembly

Assembly is the set of procedures by which a paper record is reorganized after discharge and prepared for further processing. The extent to which a record is reorganized varies among facilities. The need to reorganize the record arises from the differences between the order of the sections and documents of the record as filed on the patient unit and the order of the sections and documents of the record used in postdischarge processing. The patient care unit staff may place all sections pertaining to physician documentation in the beginning of the record so that the physicians do not have to search through other sections in order to find their section, which may be time consuming. In addition, the documentation is generally organized within sections in reverse chronological order, with the most recent date on top. Reverse chronological order makes sense while the record is on the patient unit, but after the patient is discharged, this method may actually hamper record review and understanding of the hospitalization because most people are used to reading events in chronological order. Similarly, sections that were considered sufficiently important to be placed up front for ease of documentation, such as physician’s orders may be shifted after the patient is discharged so that the overall record may be more easily read.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree