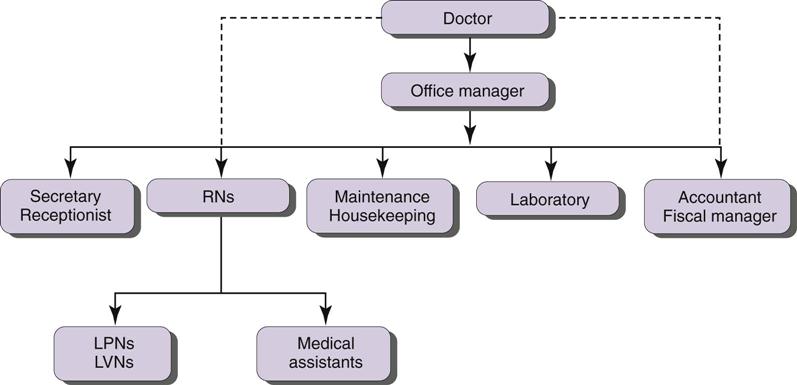

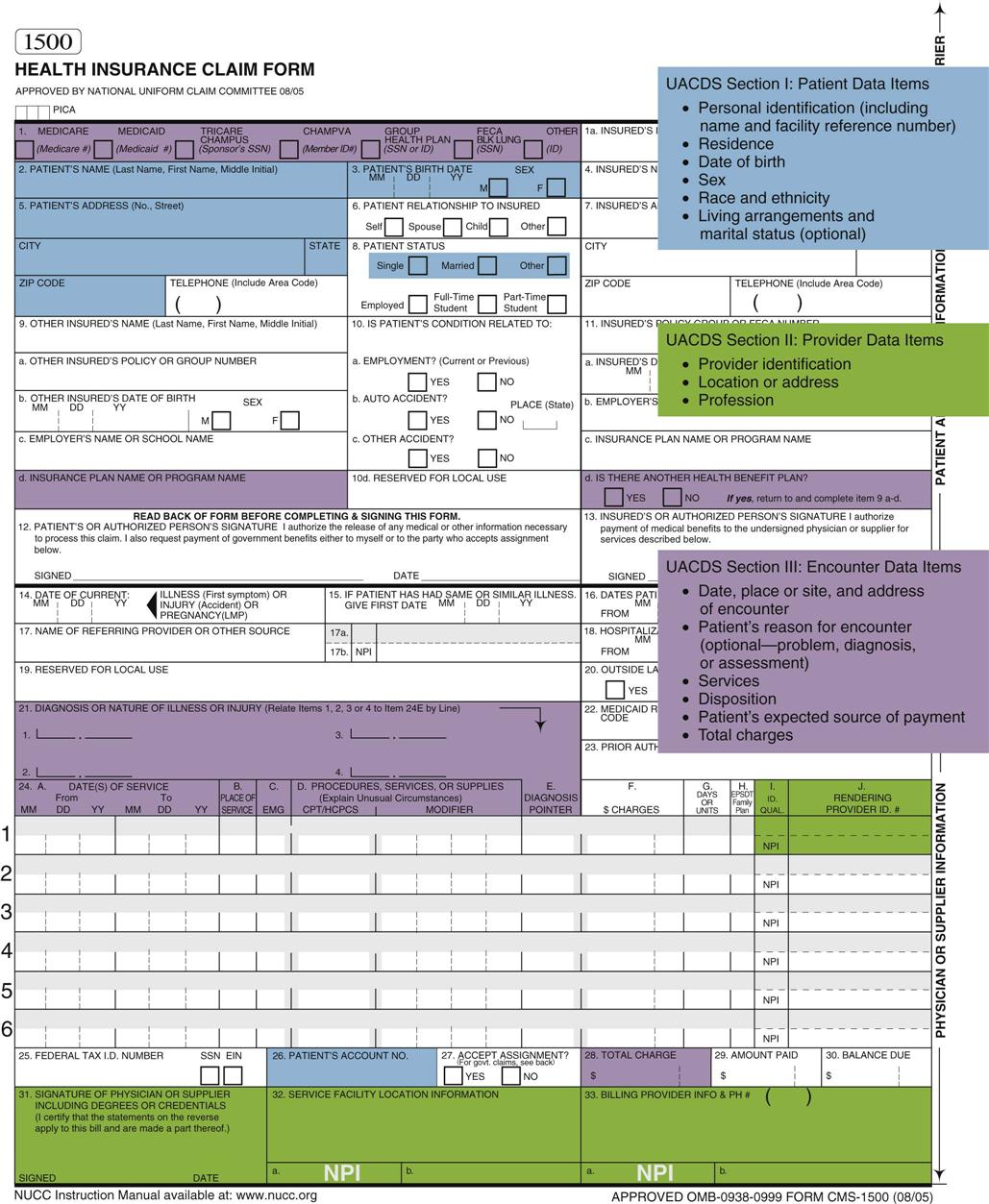

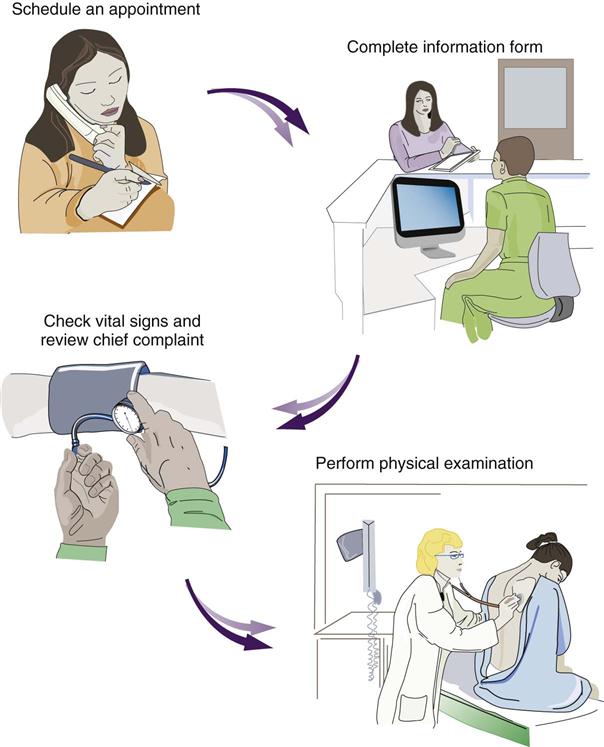

Angela Kennedy By the end of this chapter, the student should be able to: 1. List and describe four ambulatory care facilities. 2. List and describe three types of long-term care settings. 3. Describe the behavioral health care setting including the type of care provided. 4. Describe the rehabilitation health care setting including the type of care provided 7. List and describe the data sets unique to non-acute care facilities. Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) ambulatory care ambulatory care facility ambulatory surgery ambulatory surgery center (ASC) baseline cancer treatment center clinic cognitive remediation Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) Community Health Accreditation Program (CHAP) Data Elements for Emergency Department Systems (DEEDS) dialysis dialysis centers electronic data interchange (EDI) encounter group practice home health care hospice laboratory long-term care facility mobile diagnostic multispecialty group National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) pain management treatment center palliative care physiatrist physician’s office picture archiving and communication system (PACS) primary care physician (PCP) primary caregiver radiology Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) Resident Assessment Protocol (RAP) respite care retail care skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) triage Uniform Ambulatory Care Data Set (UACDS) Urgent Care Association of America (UCAOA) urgent care center visit So far, this text has addressed what occurs in an acute care facility, including how data are collected and by whom. Previous chapters mentioned the special data requirements of certain diagnoses and other health care facilities. In this chapter these other health care facilities—ambulatory care, long-term care (LTC), behavioral health, rehabilitation, home health, and hospice—are described in more detail. The most important thing to remember is that the skills and the knowledge presented thus far in this text are applicable to any health care delivery system. Demographic, financial, socioeconomic, and clinical data are collected in all settings. The volume and types of physician data, nursing data, and data from therapy, social services, and psychology vary significantly, depending on the diagnosis and the setting. In addition to discipline-specific data requirements, health care facilities must also comply with the licensure regulations of the state in which they operate. The regulations may include very specific documentation requirements based on the type of care provided. Further, all facilities seeking full Medicare reimbursement must comply with the Medicare Conditions of Participation. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Web site should be consulted for detailed information about those requirements. Health information management (HIM) professionals who are employed in special health care settings should become familiar with the unique data requirements of those settings. The Joint Commission (TJC) offers accreditation to all providers discussed in this chapter, either independently or in conjunction with the host facility. Ambulatory, or outpatient, care is provided in a brief period, typically in 1 day or in less than 24 hours. This timing distinguishes it from inpatient care, in which the patient is admitted and is expected to stay overnight. As discussed in Chapter 1, a physician’s office is only one type of ambulatory care setting. Although other types of ambulatory care settings provide different services from a physician’s office, the basic clinical flow of events is similar. Ambulatory care services are the most frequently utilized patient care service in the health care industry. Changes in reimbursement methodologies and innovations in technology and medicine during the 1980s and 1990s can explain the shift from care provided in acute, inpatient to ambulatory settings. The term ambulatory care refers to a wide range of preventive and therapeutic services provided at a variety of facilities. Patients receive those services in a relatively short time. Facilities render services on the same day that the patient arrives for treatment or, in some cases, within 24 hours. Therefore the terms admission and discharge have little or no relevance in ambulatory care. In the ambulatory care environment, the interaction between patient and provider is referred to as an encounter or a visit. Beyond the time frame stated previously, the services rendered in ambulatory care facilities vary widely. Each type of facility has its own specific data collection, retention, and analysis needs. However, the general flows of patient care are similar. The patient initiates the interaction, gives demographic and financial data to the facility, meets with the provider, who documents the clinical care, and the patient then implements any follow-up instructions, such as diagnostic testing or a visit to a specialist. A physician’s office is one type of ambulatory care facility. Some physicians have offices attached to their homes; others have space in office buildings or in a medical mall (a building that contains only health care practitioners in a variety of specialties). Still others are associated with different types of facilities and, as employees, maintain offices in those facilities. Some physicians do not see patients at all. For example, a pathologist examines tissue samples in a laboratory. Some radiologists examine only radiographs and other types of imaging results. In general, these physicians give results of those examinations to another physician to discuss with the patient. For the purposes of this section, only physicians who see patients in their offices are discussed. Sometimes physicians share office space and personnel with other physicians to reduce the cost of maintaining an office, to share financial risk, to increase flexible time, and to improve continuity of care. This type of physician’s office is called a group practice. For example, several physicians working together may need only one receptionist. Sharing office space and personnel also provides increased opportunities for professional collaboration among physicians and can improve the continuity of care for the patients served by the practice. Administrative responsibilities of the practice may be shared by all physicians in the practice. Physicians in a group practice share the burden of being “on call” or available 24 hours a day and are afforded emergency, vacation, and holiday coverage by their colleagues. Physicians in a group practice can distribute the cost of capital investments, innovations, and technology across the practice and reduce the individual financial burdens. Physicians may share a physician’s assistant or nurse practitioner. Staffing of this nature may be cost prohibitive in a solo practice. Group practices may have only one type of physician, such as a group of family practitioners. Frequently, these physicians not only share office space and personnel but also see one another’s patients. To help one another with their patient loads, the physicians must also collaborate in developing and maintaining relationships with insurance companies. Another combination of physicians may consist of several different specialties; this arrangement is called a multispecialty group. A family practice physician may be in a group with a pediatrician and a gynecologist, for example. One of the advantages of a multispecialty group practice is the convenience of centralized care that it provides for the patient. Another administrative advantage of a group practice is the ability to centralize record keeping. Whether the patient records are maintained in paper or electronic form, centralization offers substantial cost savings and efficiency. A clinic is a facility-based ambulatory care service that provides general or specialized care such as those provided in a physician’s office. Clinics may be funded or established by charitable organizations, the government, or different types of health care facilities. For example, a community health center is a type of clinic that provides primary or secondary care in a specific geographical area. Many of these centers are located in areas accessible to populations that have challenges with accessing health care. Many acute care facilities have developed clinics that resemble physicians’ office services. A hospital may have primary care and specialty clinics that serve particular patient populations, such as an infectious disease clinic or an orthopedic clinic. Clinics may also closely resemble multispecialty group practices. Large teaching facilities may be affiliated with many clinics. The clinic may be part of the physicians’ general practice, the physicians may be employees of the parent facility, or they may donate their time, often called in-kind service. An urgent care center provides unscheduled care outside the emergency department (ED) on a walk-in basis. An urgent care center treats injuries and illnesses that are in need of immediate attention but are not life threatening. Urgent care centers are usually stand-alone facilities equipped with on-site diagnostics and point-of-care medication dispensing. Use of urgent care centers is encouraged by payers and managed care organizations. The centers may be stand-alone or affiliated with a clinic, group practice, or hospital. In 2009, the Urgent Care Association of America (UCAOA) established criteria for urgent care centers. The American Medical Association grants the specialty in urgent care medicine (UCM) to physicians who choose to specialize in the discipline. Practitioners are licensed in the state in which they operate. Urgent care accreditation is offered by TJC. The Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Ambulatory Care (CAMAC) and National Patient Safety Goals to Reduce Medical Errors guide the accreditation process. The following sections describe a hypothetical visit to a physician’s office to trace the clinical flow of a patient’s data through the office and list the data that are collected. This visit is a general guide to the events to illustrate the flow of health information in the ambulatory care settings as previously mentioned. Figure 8-1 shows the flow of activities in a typical physician’s office. A patient can generally choose the physician he or she will visit as long as the physician chosen is accepting new patients. However, a patient who expects his or her insurance plan to pay all or part of the cost of the visit must take into consideration whether the physician is included in the insurance plan. If payment is an issue, the first step in selecting a physician is to determine whether that physician participates in the patient’s insurance plan. The patient may also ask friends and family members for recommendations. If the patient needs to see a specialist, such as a cardiologist, some insurance plans require that the primary care physician (PCP) refer the patient to a specific physician. Some specialists, such as thoracic surgeons, see only those patients who have been referred by other physicians. Thus the visit is initiated either by the patient or by referral and may be influenced by the patient’s insurance plan. Some insurance plans allow patients to self-refer for certain services, such as obstetrics and gynecology. After choosing a physician, the patient calls the office for an appointment. Very likely, the patient will speak to someone who works with the physician. The individual who answers the telephone and handles the appointments may be any one of a number of different allied health professionals, such as a receptionist, a medical secretary, or a medical assistant. A receptionist usually handles the telephones, does some filing, and schedules appointments. A medical secretary has a more detailed knowledge of office procedures, scheduling, filing, and billing. A medical assistant has all of that similar knowledge and some basic clinical knowledge, such as measuring and recording blood pressure and temperature, changing dressings, and assisting the physician in examining and treating the patient. Medical secretaries and medical assistants have generally received formal training, particularly if they are certified in their fields. Other personnel who support the physician include physician’s assistants, nurses, and advanced practice registered nurses. A physician’s assistant (PA) is a highly trained clinical professional who collect a variety of data, including the medical history, and assist the physician in diagnosing and treating patients. PAs undergo at least 2 years of training, including rotations through multiple specialties. An Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) has completed either a Master of Nursing or a Doctor of Nursing degree and additional training in their speciality. APRNs include certified registered nurse anesthetists, certified nurse-midwives, clinical nurse specialists, and certified nurse practitioners. APRNs may deliver primary care and often work in areas where there are not enough physicians. PAs and APRNs require state licensure to practice and the extent to which they may practice is determined by state regulations. Individual facilities further specify practice within the facility. Figure 8-2 shows some employees common in a physician’s office. Suppose that a physician’s office has a number of different staff members and employs a receptionist to handle telephone calls and appointments. When the patient calls for an appointment, the receptionist asks for the patient’s name and telephone number and inquires whether he or she is a current patient. The patient’s status will be verified, often while he or she is still on the phone. It is very important to know whether the patient is a current patient, because a new patient requires more data collection, which takes more of the staff’s time, and a longer appointment with the physician. Also, if the physician is not taking new patients, the patient must be directed to another physician. The receptionist also asks why the patient wants to see the physician, information that aids in scheduling. A regular patient coming in for a flu shot takes far less of the physician’s time than does a new patient who complains of stomach pains. Identification of a new versus an established patient is also important for billing of physician services. The receptionist will ask the patient whether he or she is insured and who the payer is. If the physician does not accept the patient’s insurance, it is preferred that the patient know this before the visit so that the method of payment can be determined or an alternate physician may be chosen. The office staff will verify the patient’s insurance before the visit—protecting the patient from incurring unnecessary bills. When the patient gets to the office, the receptionist asks the patient to fill out some forms. On these forms, the patient provides personal data: name and address, past medical history, emergency contact, and how the patient intends to pay for the services. The receptionist or a medical secretary may then enter some or all of this data into the electronic registration system. Some electronic record systems allow the patient to complete the forms online, eliminating the paper and data entry step. Patients will sign forms that authorize the physician to treat them, to release information to their insurance companies, and to acknowledge their receipt of the physician’s statement of privacy policies. In a paper-based environment, a folder is created for each new patient, labeled by name and medical record number, and used to hold the personal data form as well as any other documentation, such as a copy of the insurance card, the clinical notes, and copies of reports and test results. At each subsequent visit, the folder would be retrieved and visit data added. Historically, the folder has been the only record; however, capturing the administrative and clinical data in a point-of-care information system instead of on paper is becoming increasingly common. Computerization offers options for alerts and reminders for patient health care maintenance and provides easy access for staff and clinicians for patient care and billing purposes. Once the administrative record-keeping processes are completed, a medical assistant or nurse measures and records the patient’s temperature, blood pressure, height, and weight—all data that develop a profile of information about the patient and the visit. If this is the patient’s first visit, this profile is called the baseline. It is the information against which all future visits will be compared. Eventually, the physician meets the patient and performs and documents the appropriate level of history and physical. Perhaps the physician recommends tests to determine the extent of disease or to help determine the diagnosis. If the diagnosis is clear, the physician prescribes therapeutic treatment at this visit, which could be medications (prescription), therapy services, diagnostic procedures (radiology, laboratory) or referral to another physician. Before the patient leaves the physician’s office, he or she either remits payment for the visit or signs a release for the insurance company. For managed care patients, a copay may be required, which is paid at the time of the visit. Table 8-1 contrasts care events in acute care and ambulatory care settings. TABLE 8-1 CONTRAST BETWEEN KEY AMBULATORY AND ACUTE CARE EVENTS Minimum data sets are the key data elements about the patient and the health care he or she received. Table 8-2 contains a summary of the data sets discussed in this chapter for use in various health care settings. In ambulatory care, the minimum data set is called the Uniform Ambulatory Care Data Set (UACDS). The UACDS was developed in 1989 by committees working under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Reporting of this data is mandatory for facilities who accept Medicare and Medicaid payments. The data set was approved by the National Committee on Vital and Healthcare Statistics (NCVHS) in 1989 and is utilized to improve data comparison of ambulatory and outpatient facilities. The data set provides uniform definitions to aid in analyzing patterns of care. Box 8-1 lists the 15 elements of the UACDS; Figure 8-3 shows the UACDS data elements in relation to the CMS-1500 form. TABLE 8-2 Practitioners are licensed in the state in which they operate. Ambulatory care accreditation is offered by TJC and the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC). Emergency departments (EDs) are unique to hospitals, specifically acute care facilities. They are designed to handle patients in life-threatening situations or crises. Acutely ill patients who are admitted to the hospital from the ED will become inpatients. In rural and community health settings, the ED is often utilized to host clinics and visiting physicians who provide specialty services. Access to diagnostic equipment and personnel make it an attractive location to host services not otherwise provided to the community. These encounters are scheduled during non-peak, routine daytime hours. These visits often lead to inpatient admissions. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) of 1986 was enacted in response to the practice of hospitals refusing to treat indigent patients and transferring such patients to charity care hospitals. EMTALA requires hospitals with EDs to conduct a medical screening examination on any individual who presents for such a purpose. The hospital is obligated by law to stabilize the patient, which may result in the treatment of the patient’s condition. Because EMTALA prohibits the hospital from refusing to treat an emergency patient who cannot pay for the services provided, hospitals comply with EMTALA by deferring the request for insurance information until after the medical screening examination. It should be noted that EMTALA does not prohibit billing of the patient subsequent to the visit. Emergency department services vary dramatically. Broken legs and heart attacks are typical cases. A trauma patient is defined as a patient with a serious illness who has a high risk of dying or suffering morbidity from multiple and severe injuries. Trauma patients often are treated first in the ED and are stabilized there before being admitted to the hospital as inpatients. Because the services vary so much, the facility must determine the order in which to treat the patients. The policy of “first come, first served” does not make much sense when the first patient has strained a ligament and the second patient is experiencing a myocardial infarction. Therefore patients are screened as part of the registration process to determine the priority with which they will be treated. This prioritization process is called triage and is generally performed by a registered or advanced practice nurse. In some emergency departments, a separate section of the department is set aside for noncritical services. Noncritical services in this scenario may include minor wound repair, for example. The ED is staffed with physicians, nurses, and medical secretaries/unit clerks. The physicians in this department are highly qualified to handle the various types of illnesses and injuries of the patients who seek treatment in the ED. In one room a physician may treat a child with a bead stuck in the ear and in the very next room may diagnose and treat a patient who was involved in a major traffic accident and is unconscious and bleeding internally. The nurses also have a high level of skills in order to provide nursing care for these patients. The unit secretary in this department is very helpful in facilitating the flow of patient care, making sure that the physician’s orders are followed in timely fashion, requesting patient records from the HIM department, and following up with other departments for diagnostic tests that need to be performed or obtaining test results that are needed for diagnosis and subsequent treatment. Because the ED is located within a hospital, other allied health professionals are available for radiology, laboratory, respiratory, and other services required by the patients. Because the pace in the ED is fast, data collection must be fast. In a paper-based environment, menu-based forms have long been the standard for data collection. This menu-driven data collection has facilitated the implementation of computer data collection in the ED environment. Data collection unique to the ED includes the method and time of arrival. The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) has developed a uniform data set for EDs. The Data Elements for Emergency Department Systems (DEEDS) apply to hospital-based EDs (Figure 8-4). DEEDS supports the uniform collection of data in hospital-based emergency departments to improve continuity among emergency room records. DEEDS incorporates national standards for electronic data interchange (EDI), allowing diverse computer systems to exchange information. The Essential Medical Data Set (EMDS) complements DEEDS and provides medical history data on each patient to improve the overall effectiveness of care provided in the ED. In comparison with UACDS, the elements of DEEDS are more concise and specific to the services and treatment provided in the ED.

Health Information Management Issues in Other Care Settings

Chapter Objectives

Vocabulary

Ambulatory Care

Physicians’ Offices

Settings

Group Practice

Clinic

Urgent Care Center

Services

Care Providers

Data Collection Issues

AMBULATORY CARE (PHYSICIAN’S OFFICE)

ACUTE CARE (HOSPITAL)

How to choose

Referral, advertisement, or investigation

Choices limited to facilities in which physician has privileges

Choices sometimes limited by insurance plan

Choices sometimes limited by insurance plan

Initiate contact

Call for an appointment; walk in, if permitted

Emergency department or attending physician orders admission

Collection of demographic and financial data

Receptionist, medical secretary

Patient registration, patient access, or admissions department personnel

Initial assessment

Vital signs and chief complaint recorded by physician, nurse, or medical assistant

Nursing assessment

Physician responsible for history and physical examination

Plan of care

Prescriptions, instructions, diagnostic tests, and therapeutic procedures performed on an ambulatory basis

Medication administration, instructions, and diagnostic tests performed on an inpatient basis

Data Sets

DATA SET

SETTING

Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set (UHDDS)

Acute care

Uniform Ambulatory Care Data Set (UACDS)

Ambulatory care

Minimum Data Set (MDS)

Long-term care

Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS)

Home health care

Data Elements for Emergency Department Systems (DEEDS)

Emergency departments

Licensure and Accreditation

Emergency Department

Settings

Services

Care Providers

Data Collection Issues

Data Sets

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access