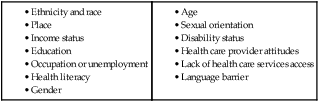

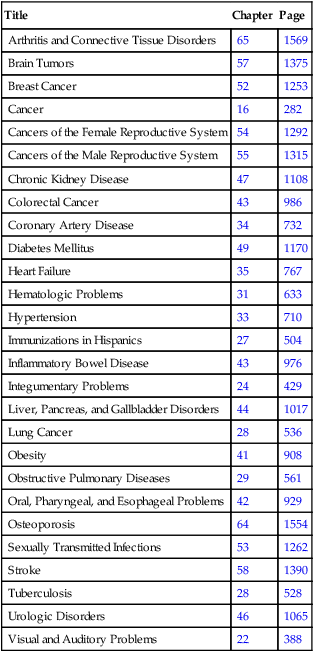

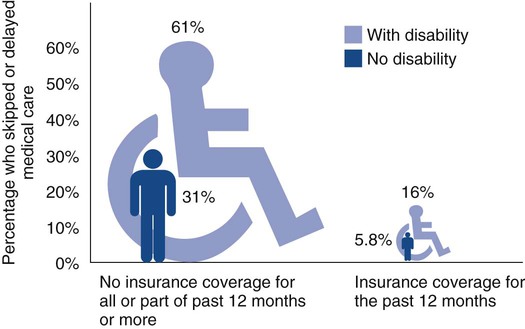

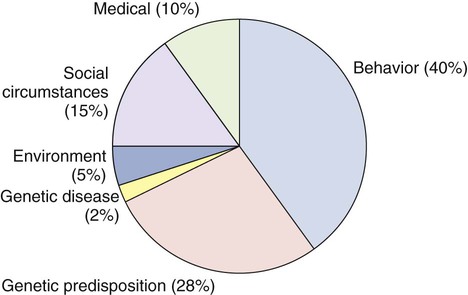

1. Identify the key determinants of health and equity. 2. Describe the primary factors that contribute to health disparities and health equity. 3. Define the terms culture, values, acculturation, ethnicity, race, stereotyping, ethnocentrism, cultural imposition, transcultural nursing, cultural competency, folk healer, and culture-bound syndrome. 4. Explain how culture and ethnicity may affect a person’s physical and psychologic health. 5. Describe strategies for successfully communicating with a person who speaks a language that you do not understand. 6. Apply strategies for incorporating cultural information in the nursing process when providing care for patients from different cultural and ethnic groups. 7. Describe the role of nursing in reducing health disparities. 8. Examine ways that your own cultural background may influence nursing care when working with patients from different cultural and ethnic groups. Why are there differences in the health status of people in America? How do these differences occur? The determinants of health are factors that (1) influence the health of individuals and groups (Fig. 2-1) and (2) help explain why some people experience poorer health than others.1 Where people are born, grow up, live, work, and age helps determine their health status, behaviors, and care. eTABLE 2-1 ETHNIC DIFFERENCES IN RESPONSE TO DRUGS ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme. Source: Chaudhry I, Neelam K, Duddu V, et al: Ethnicity and psychopharmacology, J Psychopharmacol 22:673, 2008. eTABLE 2-2 Adapted from Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2004, Saunders. Factors in a person’s social and physical environment, including personal relationships, workplace, housing, transportation, and neighborhood violence, all contribute to health status.1 For example, the risk of youth homicide is much higher in neighborhoods with gang activity and high crime rates. The physical environment in which one lives, works, and plays may expose a person to such risks as environmental hazards (workplace injuries), toxic agents (chemical spills, industrial pollution), unsafe traffic patterns (lack of sidewalks), or absence of fresh and healthy food choices. The amount and quality of health care available also contribute to an individual’s health. For example, in some states, health care organizations have reduced the number of Medicaid patients they will cover. Although the use of emergency departments (EDs) for health care is increasing, they are not usually set up to provide primary or long-term follow-up care. In addition, the number of EDs, particularly in rural areas, is decreasing.2 These determinants of health can either improve a person’s health status or put an individual at risk for disease, injury, and mental illness. The vision of the government’s Healthy People 2020 is to create a society in which all people live long, healthy lives (see Table 1-1). This report (discussed in Chapter 1 on p. 5) includes measures that can be used to reflect the health status of the U.S. population.3 Health disparities are differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality rate, and burden of diseases that exist among specific population groups in the United States because of social, economic, or environmental disadvantages. Health disparities can affect population groups based on gender, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geography, sexual orientation, disability, or special health care needs.4,5 Health equity is achieved when every person has the opportunity to attain his or her health potential and no one is disadvantaged. Many factors and conditions can lead to the development of health disparities (Table 2-1). Awareness of these factors will assist you in providing optimal care for your patients. In addition, federal agencies are required to list a minimum of five race categories: white, black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.6 People are asked to identify their race using one or more categories. In this book the terms ethnicity and race are used interchangeably or together. Despite dramatic improvements in treatments to prolong life and improve quality of life for most individuals, racial and ethnic minorities have benefited far less from these advances. Disparities are generally determined by comparing population groups. Currently in the United States, based on the latest census, racial and ethnic minority groups include Hispanics/Latinos 16.3%, African Americans 12.6%, Asian Americans 4.8%, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders 0.2%, Native Americans and Native Alaskans 0.9%, and two or more races 2.9% of the U.S. population.7 The percentages for most of these groups are expected to increase in the coming decades. Obesity and chronic illness rates for diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, cancer, and stroke are higher among minority people. Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences exist in health services, treatments provided, and access to health care providers. For example, African American men are less likely to be offered intervention procedures for cardiovascular disease and stroke.8,9 African American and Hispanic women are less likely to have mammography for breast cancer screening.6 Differences in access to screening and treatment exist even when minority groups are insured at the same level as whites. When patient groups are given the same care, the treatment outcomes are similar across racial and ethnic groups.8,9 Disease risk and outcomes are also influenced by race and ethnicity. For example, compared with U.S. white and African American populations, Native Americans have a higher incidence of stroke and are more likely to die as a consequence.9 Breast and cervical cancer mortality rates are higher in Hispanic and African American women than in other American women.10–12 African Americans are three times more likely to die from heart disease compared with whites. Fortunately, numerous strategies are underway to promote health equity and reduce disparities. Approximately 25% of Americans live in nonurban or rural areas.7 Three percent of Americans live in designated frontier counties. Differences in access to health care services among frontier, rural, and urban settings can create geographic health disparities. For example, rural populations and Native Americans living on reservations may need to travel long distances to receive health care. This can result in inadequate or less frequent access to health care services. Some parts of the rural United States are considered “medically underserved” because of decreased numbers of health care providers per population. People living in rural areas have higher rates of cancer, heart disease, diabetes, depression, and injury-related deaths than people living in urban areas. For example, in rural Appalachia the rates of lung, colon, cervical, and rectal cancer are higher than the national average.13 Rural populations tend to be older than urban populations. Many rural areas have higher rates of obesity and chronic disease. Rural Americans are less likely to work for employers who provide health insurance.12,13 As a group, rural populations have lower literacy rates and poorer health behaviors (e.g., increased smoking rates, increased substance abuse, higher rates of obesity, lower rates of physical activity). Generally, smaller and more isolated rural communities with low economic resources experience greater difficulties accessing high-quality health care. Living in urban centers may also predispose a person to health disparities. Concerns about personal safety (e.g., clinics located in high-crime neighborhoods) can make patients reluctant to visit health care providers. At the same time, health care providers such as home health nurses working in high-risk areas may experience distress when they witness crime, drug use, or other illegal activities.14 Among the most obvious health behaviors affected by place are physical activity and nutrition. Safe, walkable neighborhoods with playgrounds and sources of healthy foods promote physical activity and healthy eating. Social support and networks are related to health and coping with illness. Social networks are more likely to be found in communities where neighbors interact and rely on one another. Place may have more influence on the incidence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity for women than race or ethnicity.15 People of lower income, education, or occupational status experience worse health. In addition, they die at a younger age than those who are more affluent. In fact, adults without a high school diploma or equivalent are three times more likely to die before age 65 than those with a college degree.16 Health care costs are one of the important factors that contribute to health disparities. Individuals who have no insurance, are underinsured, or lack financial resources to pay for treatment of diseases may forgo health care visits and treatments (Fig. 2-2). Patients who lack the knowledge to apply for government assistance programs (e.g., Medicaid) are also at risk. The number of uninsured Americans has increased over the past decade.17 Hazardous work environments and high-risk occupations of laborers also increase health risk and contribute to higher rates of illness, injury, and death. Health literacy is defined as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions. This includes the ability to read, comprehend, and analyze information; understand instructions; weigh risks and benefits; and ultimately make decisions and take action. Approximately 80 million Americans have limited healthy literacy.16,18 Low health literacy is associated with more hospitalizations, greater use of emergency department care, decreased use of cancer screening and influenza vaccine, decreased ability to use medications correctly, and higher mortality rates among older adults. On a daily basis, patients need to self-manage conditions such as diabetes and asthma. For example, patients with diabetes may not be able to maintain adequate blood glucose levels if they cannot read or understand the numbers on the home glucose monitoring system. The inability to read and understand medication labels can result in taking medications at the wrong time or in the wrong dose. Health literacy is discussed further in Chapter 4. Health disparities exist between men and women. Adult women use health care services more than men. At the same time, women are less likely than men to have medical insurance. Women may not receive the same quality of care (Fig. 2-3). For example, women are less likely than men to receive procedures (e.g., coronary angiography) for cardiovascular disease.19 When gender is combined with racial and ethnic differences, the disparities are even greater. (Gender Differences boxes are presented throughout this book that highlight gender differences in disease risk, manifestations, and treatment.) Older adults are at risk for experiencing health disparities in the number of diagnostic tests performed and aggressiveness of treatments used. Biases toward older adults that affect their care, or ageism, are discussed in Chapter 5. Older women are less likely to be offered mammograms. Older people of low socioeconomic status experience greater disability, more limitations in activities of daily living, and more frequent and rapid cognitive decline.20 Older adults who belong to minority groups are less likely than their white counterparts to receive screening for prostate and colorectal cancer.21 Lesbian women are more likely to be obese when compared with their heterosexual counterparts. Lesbian and bisexual women have increased risk factors for cardiovascular disease.22 Gay men have higher rates of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis infections than other groups. Gay men and lesbian women have higher smoking rates than heterosexuals. Understanding the cause of these disparities among LGBT individuals is essential to providing safe and high-quality care. One of the barriers to accessing high-quality health care by LGBT adults is the current lack of providers who are knowledgeable about their health needs. LGBT patients may also experience fear of discrimination in health care settings.23 Within many, but not all, health care settings, LGBT health care issues are now more visible. The Joint Commission requires that patients be allowed the presence of the support individual of their choice. In addition, hospitals need to adopt policies that bar discrimination based on factors such as sexual orientation and gender identification and expression. Healthy People 2020 has added an objective on LGBT health (www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=25). Certain behaviors and biases of the health care provider can contribute to health disparities. Factors such as bias and prejudice can affect health care–seeking behavior in minority populations.24 The health care system itself may also contribute to the problem of health disparities. For example, a clinic located in an area with a large Vietnamese immigrant population that does not provide translators or educational materials and financial forms in Vietnamese may limit these families’ ability to understand how to access health care. Discrimination and bias based on a patient’s race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, or ability to pay are likely to result in less aggressive or negative treatment practices. Sometimes discrimination is difficult to identify, especially when it occurs at the institutional level. Because a health care provider’s overt discriminatory behavior may not be immediately evident to the patient or yourself, it may be difficult to confront. Even well-intentioned providers who try to eliminate bias in their care can demonstrate their prior beliefs or prejudices through nonverbal communication. Many policies are in place to eliminate discrimination, but it still exists.25

Health Disparities and Culturally Competent Care

Determinants of Health

Comparison Groups

Drug Class

Clinical Response

Chinese/European Americans

Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam [Valium], alprazolam [Xanax])

Chinese require lower doses of diazepam; more sensitive to sedative effects. European Americans have a higher clearance rate of alprazolam.

Asians/European Americans

Hispanics/European Americans

African Americans/European Americans

Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline [Elavil], imipramine [Tofranil])

Asians and Hispanics require lower doses and have greater side effects. African Americans show faster response but more side effects.

Asians/European Americans

African Americans/

European Americans

Antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol [Haldol], clozapine [Clozaril])

Asians require lower doses; develop more side effects at lower dose than European Americans. African Americans’ use is more frequent and they tend to receive higher doses.

Asian Indians/whites

Analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen, codeine)

Asian Indians have higher clearance rates.

Chinese/European Americans

Analgesics (e.g., codeine)

Chinese less able to metabolize; require increased doses to achieve therapeutic effects.

African Americans/European Americans

Chinese/European Americans

Antihypertensive agents (e.g., ACE inhibitors [captopril (Capoten)], β-blockers [propranolol (Inderal)])

European Americans respond better to ACE inhibitors and β-blockers than African Americans. Chinese require lower doses of propranolol than European Americans.

Asians/European Americans

Alcohol

Asians are more sensitive to side effects.

Native Americans/whites

Alcohol

Native Americans have faster metabolism and less tolerance.

Health Disparities and Health Equity

Factors and Conditions Leading to Health Disparities

Ethnicity and Race.

Place and Health.

Income, Education, and Occupation.

Gender.

Age.

Sexual Orientation.

Health Care Provider Attitudes.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Health Disparities and Culturally Competent Care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access