CHAPTER 12 Health care for Indigenous Australians

When you finish this chapter you should be able to:

Introduction

Although Social Darwinism has no scientific credibility, it does, however, have strength with uneducated and ill-informed members of the public. Oppressive government policies were developed to manage and control Indigenous populations and had authority under the protection, assimilation and integration policies, which were underpinned by paternalistic forms of the Social Darwinian theory (Attwood 1989). Therefore, much of the social construction of who an Indigenous Australian is has been disseminated and constructed within government policies and academia and not by Indigenous Australians (McCorquodale 1997).

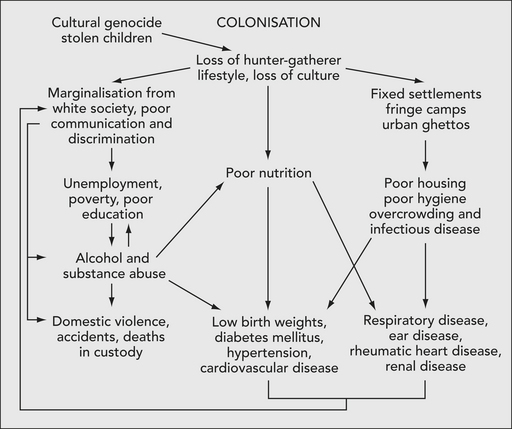

Archaeological evidence shows that Aboriginal people occupied Australia for 40 000–60 000 years prior to European arrival and possibly longer (Veth, O’Connor & Wallis 2000). The doctrine of terra nullius, the assumption that British sovereignty could be claimed over Australia as it was uninhabited, was used to justify British colonisation and was only officially overturned by the High Court of Australia with the Mabo decision (Reconciliation and Social Justice Library 1996). Until 1992, Australian law did not recognise Indigenous Australians as having legitimate rights to land, sea and occupation (Reconciliation and Social Justice Library 1996). Despite this legal affirmation, Australia continues to have a persistent difference in health status and socioeconomic disadvantage between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Matthews (1997) provides a causal pathway (Fig 12.1) to frame the links between colonisation and the current poor health and social disadvantage of Indigenous Australians. Casual pathways open up the concept of multiple outcomes from single pathways and multiple pathways to single outcomes (Stanley 2002).

This pathway (Fig 12.1) hides the savagery of the interaction between the colonists and the Aboriginal inhabitants of Australia. Within 2 years of the First Fleet’s arrival, a series of localised wars began between the British invaders and respective Aboriginal nations as the invaders ventured across Australia (Connor 2005). The Aboriginal wars continued, always as localised events, until the Coniston massacre in Central Australia in 1928 (Wilson & O’Brien 2003). Although the Aboriginal wars are now largely forgotten, it is ironic that the Aboriginal man, Gwoya Jungarai, depicted on the obverse of the two dollar coin was a survivor of the Coniston massacre (Wilson & O’Brien 2003). This coin should serve as a reminder of the bravery of Aboriginal peoples.

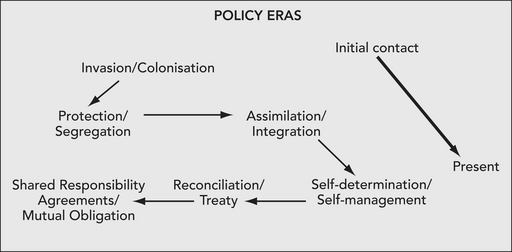

Interwoven within Matthew’s (1997) causal pathway are the historical eras of governmental policies. In Figure 12.2 the official dates of when these policies were enacted are not detailed as implementation occurred at different times for each state and territory. Historically, Indigenous people’s access to government services was circumscribed by the colonial administrative systems after federation in 1901 (Anderson 2001).

Figure 12.2 Succession of government policies imposed on Indigenous Australians

Source: Adapted from Anderson 2006, Horton 1994, Wearne 1980

History of Aboriginal controlled health services: 1970 reforms and community health

The innovative approach by the AMS to primary health care was based on the Alma-Ata declaration (1978) and mirrored contemporary international aspirations for accessible, effective, appropriate, needs-based health care with a prevention and social justice focus (Hunter et al 2005). AMSs are now known as Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs), of which there are more than 130 across Australia (National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation [NACCHO] 2006; NATSIHC 2003b: 18–19).

By definition, an ACCHS must be:

The distinguishing characteristics of ACCHSs include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection