Health Assessment of Older Adults

Objectives

1. Identify different levels of assessment.

2. Describe the difference between subjective and objective data.

3. Discuss the importance of thorough assessment.

4. Describe appropriate methods for structuring and conducting an interview.

5. Identify approaches that facilitate a successful physical examination of the older adult.

6. Discuss the modifications used when preparing an older person for a physical examination.

7. Describe the techniques used when performing a physical examination.

8. Explain the adaptations used when assessing vital signs in older adults.

Key Terms

assessment (ă-SĔS-mĕnt) (p. 151)

auscultation (ăw-skŭl-TĀ-shŭn) (p. 155)

inspection (Ĭn-spĕk′shen) (p. 155)

palpation (păl-PĀ-shŭn) (p. 155)

percussion (pĕr-KŬ-shŭn) (p. 155)

screenings (skrē′nĭng) (p. 157)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

Health assessment of older adults can be done on several levels, ranging from simple screenings to complex, in-depth evaluations. To perform assessments accurately, nurses and other health care providers who gather information regarding older adults must possess the necessary knowledge and skill to perform the assessments correctly. They must know how to use diagnostic tools and equipment safely. Furthermore, they must be knowledgeable and sensitive to the unique needs and characteristics of older adults.

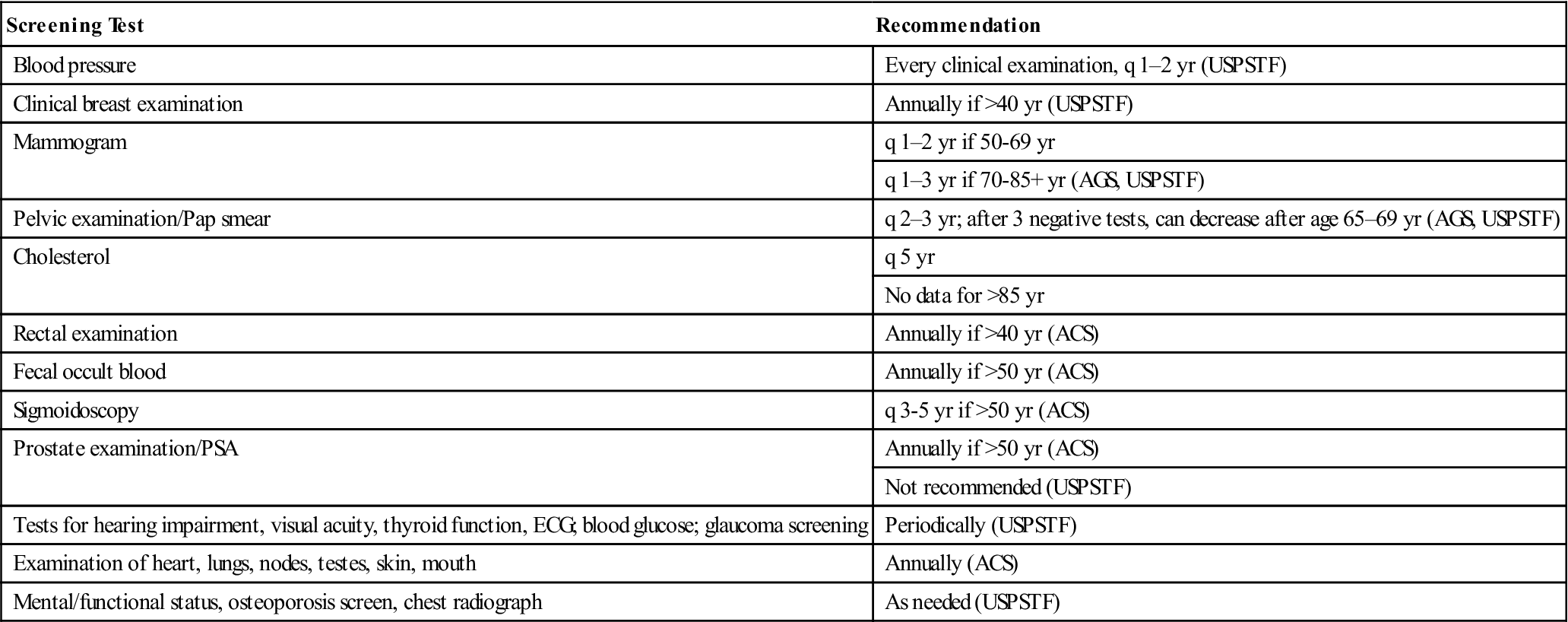

Health screening

Health screenings are done to identify older individuals who are in need of further, more in-depth assessment (Table 8-1). Screening for high blood pressure, hearing problems, foot problems, and problems with activities of daily living are commonly performed at senior citizen centers and health clinics. Screening services are often provided by medical and nursing schools or other health groups committed to helping needy older persons. Many screenings are performed by lay individuals working under the direction of professionals. Special screenings for depression and suicide risk, although less common, are recommended for the older adult population. Some problems are more common among certain ethnic populations. Screening ethnic populations most at risk for problems can promote early identification and treatment of problems (Table 8-2).

Table 8-1

Preventive Medicine: Screening Recommendations for Older Adults

| Screening Test | Recommendation |

| Blood pressure | Every clinical examination, q 1–2 yr (USPSTF) |

| Clinical breast examination | Annually if >40 yr (USPSTF) |

| Mammogram | q 1–2 yr if 50-69 yr |

| q 1–3 yr if 70-85+ yr (AGS, USPSTF) | |

| Pelvic examination/Pap smear | q 2–3 yr; after 3 negative tests, can decrease after age 65–69 yr (AGS, USPSTF) |

| Cholesterol | q 5 yr |

| No data for >85 yr | |

| Rectal examination | Annually if >40 yr (ACS) |

| Fecal occult blood | Annually if >50 yr (ACS) |

| Sigmoidoscopy | q 3-5 yr if >50 yr (ACS) |

| Prostate examination/PSA | Annually if >50 yr (ACS) |

| Not recommended (USPSTF) | |

| Tests for hearing impairment, visual acuity, thyroid function, ECG; blood glucose; glaucoma screening | Periodically (USPSTF) |

| Examination of heart, lungs, nodes, testes, skin, mouth | Annually (ACS) |

| Mental/functional status, osteoporosis screen, chest radiograph | As needed (USPSTF) |

Table 8-2

Suggested Preventive Screenings Based on Ethnicity

| Demographic Group | Preventive Screenings |

| African American | Blood pressure, blood diseases, breast cancer, prostate cancer, weight gain, vision loss, diabetes, cholesterol |

| Mexican American | Weight gain, diabetes, cervical cancer |

| Southeast Asian | Depression, diabetes |

| Filipino American | Blood pressure, diabetes |

| Pacific Islander | Weight gain, diabetes |

| American Indians | Weight gain, diabetes, hearing loss |

| European American | Breast cancer |

Modified from GeroNurseOnline.org (geronurseonline.org).

Screenings are not designed to provide treatment; rather they are intended to identify older individuals with significant findings and refer them to the most appropriate health service provider (i.e., physician, social worker, dietitian, or nurse). Early screenings and appropriate referrals help ensure that older individuals who are most in need of care are seen in a timely manner. They also help reduce frustration in older adults and wasteful use of time and resources. Depending on what is being evaluated, health screenings may be conducted in person, by telephone, by telecomputer, or, less commonly, by mail surveys.

Health assessments

In-depth health assessments are time-consuming and must be performed by skilled professionals. Nurses perform health assessments of older adults in the community, in clinics, and in institutional settings. Health assessment includes the collection of all of the important health-related data using a variety of techniques. Data are all of the information a nurse gathers about a person. This information is used to formulate nursing diagnoses and to plan patient care; therefore, it is essential that accurate and complete data be collected. Data can be either objective or subjective.

Objective data include information that can be gathered using the senses of vision, hearing, touch, and smell. Objective information is collected by means of direct observation, physical examination, and laboratory or diagnostic tests. Because objective data are concrete by nature, all trained observers should report similar findings about a person or that person’s behavior at any given point in time. Behaviors such as crying, limping, and clutching the abdomen can be verified by anyone who observes the patient. Rashes, skin lesions, and wound drainage are likewise observable to anyone. Objective data can be made more precise and specific by using meters, monitors, and other measuring devices. A blood pressure reading, a change in weight, the size of a wound, the volume of urine, and laboratory test results are all examples of specific objective data. Whenever possible, objective data should be stated using specific information because accurate and precise data enhance the nurse’s ability to determine changes in a person’s health status. For example, it is better to actually take a temperature reading than to touch the skin and determine that it feels warm. Both are objective observations, but one is more precise than the other.

Subjective data are information gathered from the older person’s point of view. Fear, anxiety, frustration, and pain are examples of subjective information. Subjective data are best described in the individual’s own words, such as “I’m so afraid of what is going to happen to me here” or “It hurts so much I could die!”

When performing a health assessment on an older person, the nurse needs to modify his or her usual approaches and techniques to make them more appropriate for older adults.

Interviewing older adults

Interviews such as those conducted during admission to a clinic or institution are likely to be planned and conducted in a formal manner. Other interviews may be spontaneous, informal, and based on an immediate need recognized by the nurse. Before beginning an interview with an older person, the nurse should plan ways to establish and maintain a climate that promotes comfort and develops trust. This includes preparing the physical setting, establishing rapport, and structuring the flow of the interview. During this planning phase, the nurse should take into consideration the unique needs of the older person.

Preparing the Physical Setting

The environment where the interview will take place should be chosen carefully. Distractions should be minimal; noise from televisions, radios, and public address systems should not be loud enough to distract the older adult or interfere with his or her ability to distinguish words and understand questions. Lighting should be diffuse because bright lights or glare may make it difficult for the interviewee to see clearly. Furniture should be comfortable. Privacy is very important. Conducting the interview in a room where there is little chance of interruption is ideal. If such a place is not available, the patient’s room may provide sufficient privacy—the curtains should be drawn and the door closed. The room should be comfortably warm and should be free from drafts that might cause discomfort. Because many older adults experience urinary frequency or urgency, it is advisable either to assist them to the bathroom or to tell them that a bathroom is available nearby should they require it.

Establishing Rapport

It is most appropriate to begin the interview by greeting the older person and introducing yourself. During this first contact, it is best to address the person using his or her formal name (e.g., “Mr. Smith” or “Mrs. Adams”). Appropriate use of names indicates respect and helps build rapport. Use of the individual’s first name only without the person’s consent is presumptuous and overly familiar. This familiarity may be resented by the older person whether or not it is verbalized. When there is any doubt about the person’s preference, it is appropriate for the nurse to ask the person how he or she wishes to be addressed.

The nurse should briefly explain the purpose of the interview so that the individual will know what to expect. An explanation helps reduce anxiety that otherwise might interfere with understanding. The nurse should explain how long he or she expects the interview to last, as well as what will happen after it is completed.

Nurses should focus on and speak directly to the older person being interviewed (Figure 8-1). This notion may seem obvious, but it is often disregarded in practice. Often, a younger family member present during the interview “takes over” the responses for the older person. The conversation then takes place between the nurse and the family member while the older adult remains passive. An assertive older person might speak up and say, “Let me speak for myself,” whereas a nonassertive older adult may be left feeling frustrated and unimportant. The nurse should continue to direct the conversation to the older person and, if necessary, tactfully request that the family member allow the older person to respond first before he or she adds information. Because of necessity, in situations in which the older person is confused, nonresponsive, or does not speak English, the family member will need to be more actively included to translate or provide information.

Rapport is enhanced by first determining the problems or concerns that trouble the patient most and then focusing on those problems. This helps reduce anxiety and increases the older person’s perception that the nurse is truly concerned about him or her. Assessment should start with a look at the whole person before focusing on specifics.

Structuring the Interview

It is important to plan sufficient time for the interview. Older individuals typically have a long and complex life story to tell. Remember that the speed of recall and verbal responses may be slower with age. The individual may feel pressured or stressed if the pace of the interview is too rapid.

The nurse should try not to accomplish too much during a single interview. The effort involved in communication can be fatiguing to an older individual, particularly one with health problems. It is better to have several brief interactions lasting less than 30 minutes each rather than one long interview that leaves the patient exhausted. Nurses should be sure to stay alert for signs of fatigue (e.g., sagging head or shoulders, sighing, altered facial expression, and irritability), which indicate the need to end the interview.

During the interview, a variety of communication techniques should be used to ensure that the patient accurately understands the information. Nurses should avoid using medical jargon and should use only words that the older person understands. The nurse should speak slowly and clearly and keep messages simple but should not patronize older adults. The fact that an older person requires extra time does not mean that the person is in any way mentally impaired. Even if the older person has been diagnosed with a mental impairment, he or she deserves respectful and professional responses. Nurses must remain calm and empathetic. When the patient is speaking, the nurse should not interrupt. The nurse must listen to both the verbal and nonverbal messages being sent. Many older individuals tend to ramble in conversation and may need to be brought back on track. If this is necessary, a summary or restatement of the conversation is helpful. It is not appropriate to complete sentences for the older person. The nurse should remain attentive and calm and should allow the patient to complete his or her own sentences. Too often, the nurse’s conclusion is considerably different from the patient’s.

The nurse should try not to end an interview too abruptly. A statement such as “We’re almost done for now” prepares the older person for the end of the interaction. Many lonely persons will try to extend the conversation beyond the time the nurse has available. Setting a time for further interaction by saying, “We’ll talk again tomorrow morning” or “I’ll set up another appointment so we can talk more” can help maintain rapport. It is essential for the nurse to follow through as promised, or the patient may lose trust and refuse to communicate freely in the future.

Obtaining the health history

Before starting a physical assessment, the nurse will use interviewing techniques to obtain a health history. This history starts with basic identifying data followed by a history of past health concerns and then a review of current health issues. Some older adults are able to provide information easily, whereas others may be poor historians. Much will depend on the cognitive level of the individual and the complexity of his or her particular medical history. When the older adult is unsure of answers, it is often wise to move on to other topics and attempt to gather the information from a family member at a later time. In addition, the nurse may want to obtain information regarding the person’s family and psychosocial status. Information gathered from the history will help the nurse form an overall impression of the older person and can help the nurse focus on those areas most in need of further exploration and assessment (Box 8-1).

Physical assessment of older adults

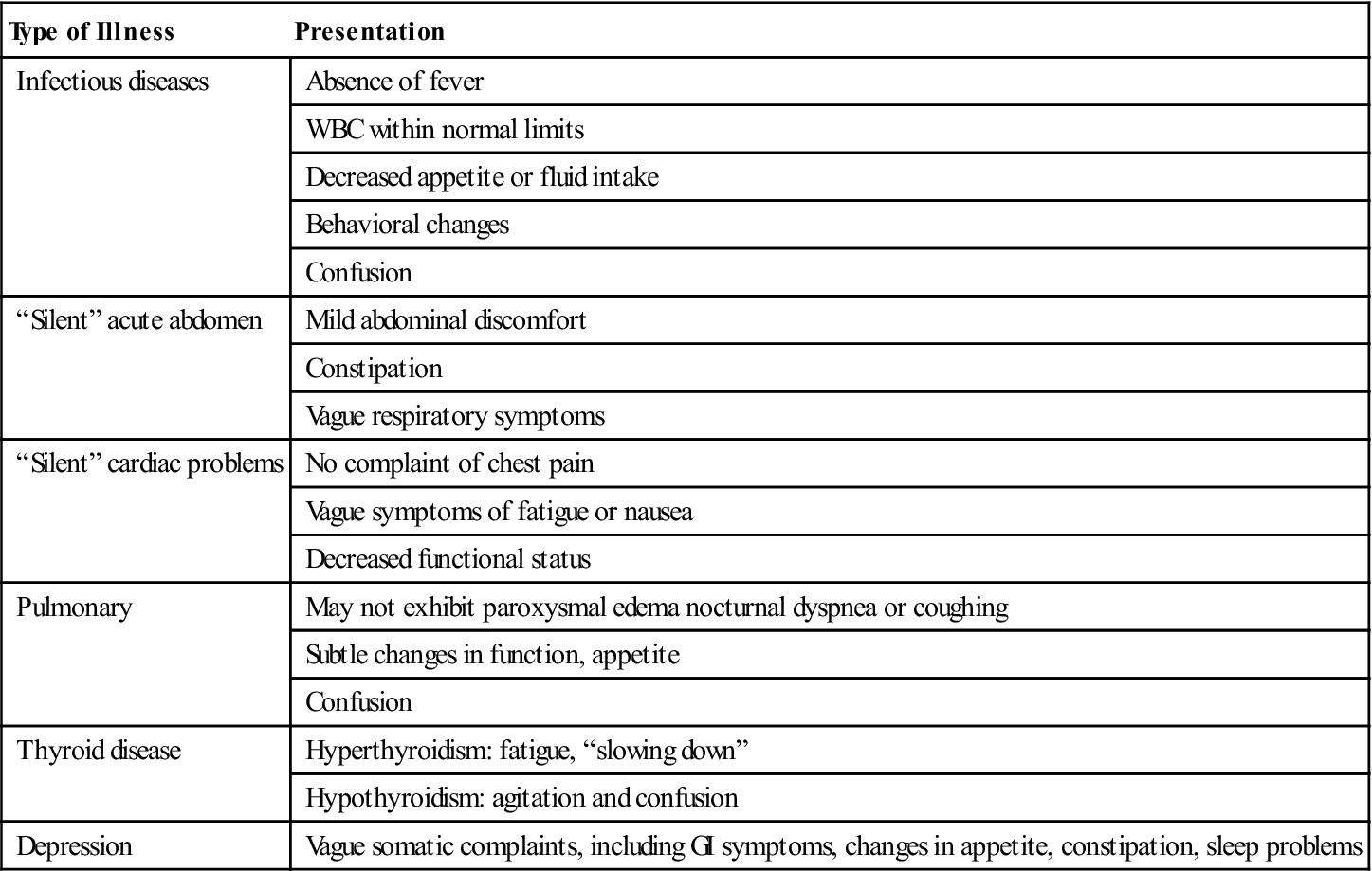

Once the history is obtained, the nurse is then ready to proceed to the physical assessment. During this assessment, objective information is obtained to accompany the subjective information offered by the older person. Objective information further helps the nurse determine the person’s abilities and limitations. It may verify the subjective information given by the older person; it may also reveal problems that were previously unrecognized. When assessing older persons, it is important that nurses pay close attention not only to obvious physiologic changes, but also to changes in mood or behavior that may signal a change in condition. Seemingly small pieces of information can be important to the total assessment. Older adults have different physiologic responses than do younger persons. For example, a temperature change of just a few tenths of a degree may indicate the onset of an infection in an older person, rather than rising above the 100° F reading, which is expected in younger people. Other changes can be equally meaningful and may be missed or ignored if nurses are not especially careful (Table 8-3).

Table 8-3

Atypical Presentation of Illness

| Type of Illness | Presentation |

| Infectious diseases | Absence of fever |

| WBC within normal limits | |

| Decreased appetite or fluid intake | |

| Behavioral changes | |

| Confusion | |

| “Silent” acute abdomen | Mild abdominal discomfort |

| Constipation | |

| Vague respiratory symptoms | |

| “Silent” cardiac problems | No complaint of chest pain |

| Vague symptoms of fatigue or nausea | |

| Decreased functional status | |

| Pulmonary | May not exhibit paroxysmal edema nocturnal dyspnea or coughing |

| Subtle changes in function, appetite | |

| Confusion | |

| Thyroid disease | Hyperthyroidism: fatigue, “slowing down” |

| Hypothyroidism: agitation and confusion | |

| Depression | Vague somatic complaints, including GI symptoms, changes in appetite, constipation, sleep problems |

Modified from Ham R, Sloane D, Warshaw G: Primary care geriatrics: a case-based approach, St Louis, 2002, Mosby.

Physical assessment should take place in a location that promotes physical comfort of the older person. Often this will be the person’s room or a special examination room. Adequate privacy should be maintained by keeping doors and curtains closed. Care should be taken not to chill the older person while examining the body. Blankets and gowns that provide adequate warmth should be used to promptly cover the parts of the body not being assessed. If the examination is being done during physical care (e.g., during the bath), particular attention must be paid to prevent chilling caused by evaporation.

Equipment such as a flashlight, measuring tape, scale, sphygmomanometer, stethoscope, and thermometer should be collected before beginning the assessment to convey a sense of competence and to allow the assessment to progress smoothly.

Complete physical assessment should be done in an orderly manner so that no important observations are missed. Begin with an overview of the person, including general appearance, hygiene, grooming, alertness, responsiveness, and general mobility; then proceed with more focused assessments. The most common method of physical assessment is a head-to-toe approach in which the entire body is assessed systematically. Other approaches such as body system or functional approaches are also viable. Later chapters provide guidelines for assessing safety needs, nutrition, skin, elimination, activity, sleep, cognitive function, and other areas in more detail.

When performing a physical assessment, nurses use a variety of techniques, including inspection, palpation, auscultation, and percussion.

Inspection

Inspection is the most commonly used method of physical assessment in which the senses of vision, smell, and hearing are used to collect data. Skill at inspection improves the more often the technique is done. Inspection requires the nurse to be totally active, alert, and aware of everything he or she sees, hears, or smells. Inspection begins the first time we see the older adult. Even during a brief interaction, skilled nurses should be inspecting the individual, looking for anything that may indicate a change in his or her condition.

Inspection can be both general and specific. General inspection is used to detect the need for more specific inspection. For example, if the nurse observes that the older individual is eating poorly, a more specific inspection of the oral cavity may be indicated. If body odor is detected, a more specific inspection of the skin may be indicated. If the nurse hears noisy breathing, a more specific inspection of the lungs may be necessary. If gait is abnormal, a more complete assessment of the joints, muscles, feet, and nervous system is indicated.

Inspection is used when assessing the overall level of function, as well as when looking for specific areas of need within any particular area of function. When inspecting the aging individual, it is important that the nurse pay close attention to details. Adequate light (preferably natural light) should be used when trying to detect subtle changes in skin color. Size and mobility of body parts on one side of the body should be compared with those on the opposite side.

Palpation

Palpation uses the sense of touch in the fingers and hands to obtain data. Palpation is used for evaluation in many parts of a physical assessment, including pulses, temperature and texture of the skin, texture and condition of the hair, the presence and consistency of tumors or masses under the skin, distention of the urinary bladder, and the presence of pain or tenderness.

When palpating, the nurse should use the fingertips, which are the most sensitive part of the fingers. Warm hands and short fingernails promote comfort and reduce the risk for trauma to fragile older skin. Light touch should be used before deeper touch is attempted. When taking the pulse of an older person, deep palpation may occlude blood vessels. Deep pressure may also increase pain. Painful areas should be palpated last.

Auscultation

Auscultation uses the sense of hearing to detect sounds produced within the body. Heart, lung, and bowel sounds are typically assessed using auscultation. Auscultation involves the use of a stethoscope or other sound amplifier (such as a Doppler) to make the sounds louder and more easily heard. Sounds are described according to their quality, pitch, intensity, and duration. Quality describes the sound being heard through subjective terms such as crackling, whistling, or snapping. Pitch describes whether the sounds have a low or high tone. Intensity refers to the loudness or softness of the tone. Duration refers to the length of time a sound is heard. Frequency refers to how often a sound is heard. A sound can be continuous or intermittent. When sounds are intermittent, the number of times and the interval between occurrences should be determined.

Auscultation requires a quiet environment and special skills. Nurses who perform auscultation should have special training in the technique and should be knowledgeable regarding the significance of any findings.

Percussion

Percussion is a technique in which the size, position, and density of structures under the skin are assessed by tapping the area and listening to the resonance of the sound. Depending on the amount of vibration (sound) heard, the presence of masses, fluid, or air can be determined. This technique is used least often by nurses. It requires special skill and training.

Assessing vital signs in older adults

Assessment of vital signs involves all of the techniques previously discussed. When assessing vital signs, nurses should first complete a general inspection of the older adult to determine whether there are any subjective or objective observations that may affect the procedure or accuracy of the readings. Because activity level, medications, eating, stress, disease processes, and the environment can all affect vital signs, the possible contributions of these factors should be considered.

Baseline vital sign readings should be obtained during the initial contact with the older person. These readings are the basis for comparison with future readings, and they enable nurses to determine whether the person’s health status is remaining constant or changing over time.

Temperature

The general inspection helps nurses select the most appropriate route for temperature assessment. The oral (sublingual) route is used most commonly for temperature assessment. Either an electronic thermometer or a glass thermometer that does not contain mercury can be used to take an oral temperature. Electronic thermometers are preferred because they can give an accurate temperature in less than 1 minute instead of the recommended 3 minutes for a glass thermometer. However, using the oral route is not always possible with older adults. Those who are edentulous (without teeth) or have poor muscle control may be unable to close the mouth tightly enough for an accurate reading to be obtained. Older adults who are unable to follow directions are also poor candidates for oral temperature checks.

Although acceptable, the rectal route should be used with caution. Use of the rectal route can be psychologically traumatic to older adults, particularly if they are alert but unable to cooperate with an oral temperature. The rectal route should not be used in older persons who have undergone rectal surgery or have rectal bleeding. Rectal readings can be affected by the presence of stool in the rectum. Rectal temperature readings reflect changes in core body temperature more slowly than do oral readings.

Use of the axillary route is not common in older adults. This route is time-consuming, and the accuracy of temperature readings may be affected by environmental conditions.

Determination of body temperature using a sensor that measures the temperature of the tympanic membrane has received mixed reviews. This method has advantages and disadvantages. Use of the tympanic sensor takes seconds only, is not invasive, and does not require patient cooperation; however, the readings obtained using this method are not as accurate as originally claimed, particularly when the device is not used precisely as directed. Individual agencies need to determine whether this method of assessment is adequate for their needs.

In general, healthy, active older individuals are able to maintain core body temperature within normal limits. The accepted norm for oral temperature is 98.6° F ± 1° F (or 37° C ± 0.6° C). Studies have shown that older adults, particularly those older than 75 years, have an average core body temperature of 97.2° F (36° C). This decrease may be a result of inactivity, decreased subcutaneous fat, an inadequate diet, or environmental factors. Environmental temperature appears to play a greater role in older adults because their thermoregulatory control systems are not as efficient as in younger individuals.

Pulse

Before the nurse assesses the pulse, the patient should be positioned so that he or she is comfortable and the nurse has access to the desired site. Position should be consistent (e.g., lying, sitting, or standing) each time the pulse is checked; this will provide meaningful readings for comparison.

Pulse can be assessed at various sites on the body, including the temporal, carotid, brachial, radial, femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis arteries, as well as at the apex of the heart (Figure 8-2). When possible, the pulses on both sides of the body should be assessed and compared.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree