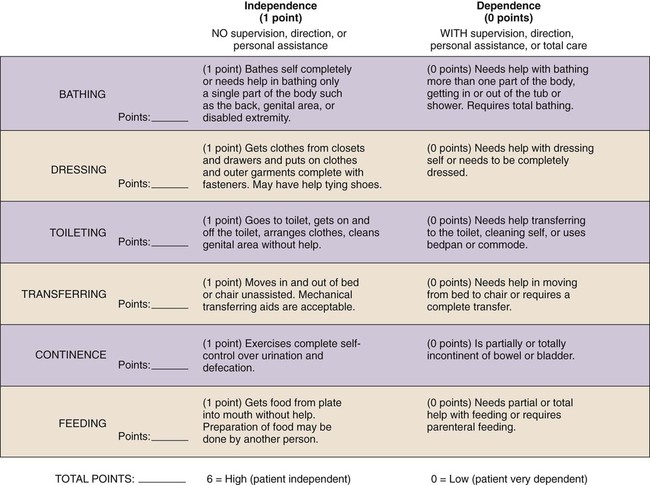

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. List the essential components of the comprehensive health assessment of an older adult. 2. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the use of standardized tools in the gerontological assessment. 3. Describe the purpose of the inclusion of functional assessment when caring for an older adult. Assessment of the older adult requires special abilities of the nurse: to listen patiently, to allow for pauses, to ask questions that are not often asked, to observe minute details, to obtain data from all available sources, and to recognize normal changes associated with late life that might be considered abnormal in one who is younger (see Chapter 4). In gerontological nursing, assessment takes more time than it does with younger adults because of the increased medical and social complexities of living longer. The quality and speed of the assessment are an art born of experience. Novice nurses should neither be expected nor expect themselves to do this proficiently but should expect to see both their skills and the amount of information obtained increase over time. According to Benner (1984), assessment is a task for the expert. However, an expert is not always available. By using both a high degree of sensitivity, knowledge of normal changes with aging, and appropriate assessment tools, reasonably reliable data may be obtained by nurses at all skill levels. To meet the needs of our increasingly diverse population of elders, the use of questions related to the explanatory model (Kleinman, 1980) is recommended to complement the standard health history, making it applicable to everyone (Box 7-1). The responses will better enable the nurse to understand the elder and plan culturally appropriate and effective interventions. A comprehensive assessment includes psychological parameters such as cognitive and emotional well-being; caregiver stress or burden; the individual’s self-perception of health; and patterns of health and health care, education, family structure, plans for retirement, and living environment. For those living at home, a home safety assessment is important. Areas or problems not frequently addressed by the care provider or mentioned by the elder but that should be addressed are sexual dysfunction, depression, incontinence, alcoholism, hearing loss, and memory loss or confusion (Ham, 2002). The health history is followed by the physical assessment or examination at that time or at a time in the near future. Although the manual techniques of the examination do not differ significantly from those used with younger persons, knowledge of the normal changes with aging is essential for the appropriate analysis of the data obtained. When assessing persons from ethnically distinct groups, is it also necessary to be aware of cultural rules of etiquette and taboos that influence the examination (Box 7-2) (see also Chapter 5). Because of the complex interrelationship among the parts of the complete assessment process, the use of a model or tools may be helpful. The website of the Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing (New York, NY; http://hartfordign.org) provides a compilation of key tools used in assessment in their Try This series. New evidence-based protocols are regularly added. The tools and directions for their use can be viewed at http://hartfordign.org. This site is a portal to a wealth of information, especially for assessing a number of specific conditions or situations, such as fall risk or restraint use. Two tools for a basic overall assessment of older adults and those who are medically vulnerable are SPICES and FANCAPES. They use a framework with an emphasis on function at the most basic level and the extent to which assistance is necessary. When alterations are found then further assessment in that particular area is indicated (Montgomery et al., 2008). The acronym FANCAPES stands for Fluids, Aeration, Nutrition, Communication, Activity, Pain, Elimination, and Socialization and social skills. SPICES is the mnemonic for Sleep disorders, Problems with eating or feeding, Incontinence, Confusion, Evidence of falls, and Skin breakdown. Both can be used in all settings, may be used in part or total (depending on the need), and are easily adaptable to the functional pattern grouping if nursing diagnoses are used. The Fulmer SPICES has been used widely with older adults as an overall assessment tool regardless of health status or setting (Wallace and Fulmer, 2007). The acronym SPICES refers to six common geriatric syndromes of the elderly that require nursing interventions: Sleep disorders, Problems with eating or feeding, Incontinence, Confusion, Evidence of falls, and Skin breakdown. Like with FANCAPES, anything that indicates a problem in one of the categories warns the nurse that more in-depth assessment is needed. It is a system for alerting the nurse to the most common problems that interfere with the health and well-being of older adults, particularly those who have one or more medical conditions. • Identifying the specific areas in which help is needed or not needed • Identifying changes in abilities from one period of time to another • Determining the need for specific service(s) • Providing information that may be useful in assessing the safety of a particular living situation The FAST (Functional Assessment Staging) tool for Alzheimer’s disease was designed by Barry Reisberg in 1988. It has been found to be a reliable and valid measurement for the evaluation and staging of functional decline in persons with Alzheimer’s disease (Sclan and Reisberg, 1992). The tool uses ordinal ranking of seven stages beginning with what is referred to as a “normal adult” to one with “severe dementia.” This can be used to plan care and work with the individual and family to prepare for future needs. Varitions of this tool can be easily found on the internet. The Katz Index (Katz et al., 1963) has served as a basic framework for most of the measures of ADLs since that time (Figure 7-1). There are several versions of the Katz Index. One is based on a three-point scale and allows one to score client performance abilities as independent, assistive, dependent, or unable to perform. Another version of the tool assigns 1 point to each ADL that can be completed independently and a zero (0) if it cannot. Scores will range from a maximum of 6 (totally independent) to 0 (totally dependent). A score of 4 indicates moderate impairment, whereas 2 or less indicates severe impairment (see Figure 7-1). This scoring puts equal weight on all activities, and the determination of a cutoff score is completely arbitrary. Despite these limitations, the tool is useful because it creates a common language about functioning for all caregivers involved in planning overall care and discharge. The Barthel Index (BI; Mahoney and Barthel, 1965) and the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) are the two tools most commonly used in the rehabilitation setting to assess a person’s need for assistance with ADLs. The data are used for both inpatient and postdischarge planning relative to the amount of physical assistance required. In some studies the BI and FIM were found to be comparable (Sangha et al., 2005). In others the FIM was deemed preferable (Kidd et al., 1995). The BI has proved easy to use and especially useful as a method of documenting improvement of a patient’s ability. The BI ranks functional status as either independent or dependent and then allows for further classification of “independent” as intact or limited, and of “dependent” as needing a helper or unable to do the activity at all. Instruction is needed in the use and scoring of this tool before using it. The FIM is widely used and the most comprehensive functional assessment tool for rehabilitation settings. It includes measures of ADL, mobility, cognition, and social functioning. It has been widely tested and rates 18 ADLs on a seven-point scale from independent to dependent. The items are sorted into 13 motor items and 5 cognitive items. The tool is highly sensitive but complex and requires training to use accurately and to obtain interrater reliability. Ordinarily the tool is completed by the joint efforts of the multi-disciplinary team and used for both planning and evaluation of progress. Use of this instrument can be requested from the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (www.udsmr.org).

Health Assessment

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

The Health History

Physical Assessment

Spices

Functional Assessment

Activities of Daily Living

Katz Index

Barthel Index and Functional Independence Measure

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Health Assessment

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access