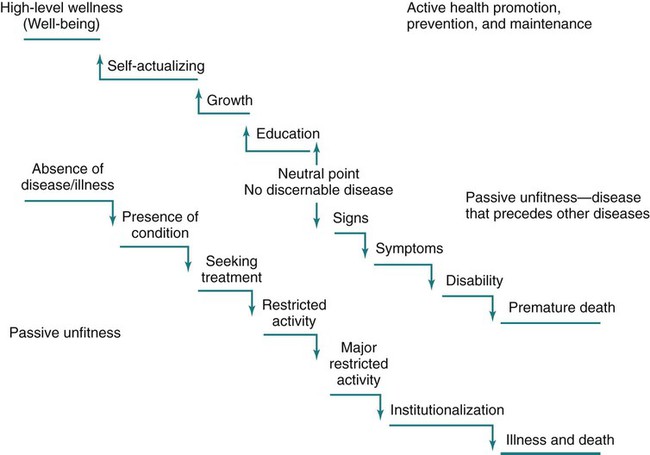

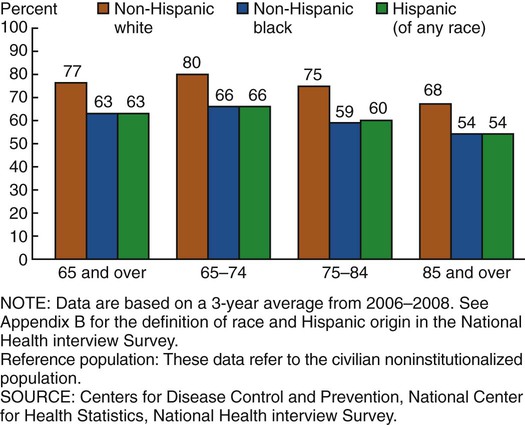

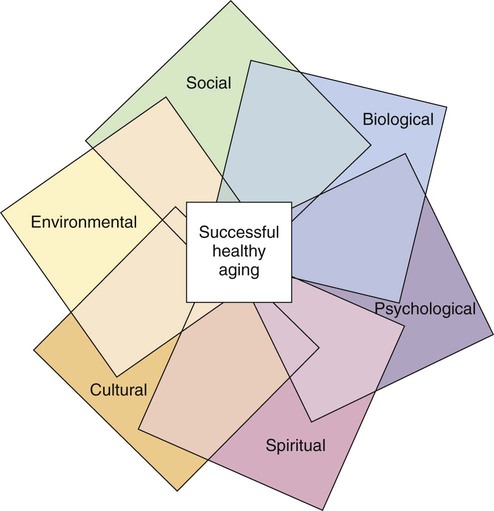

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Differentiate between the concepts of health and wellness. 2. Describe the health status of older people. 3. Describe the goals of Healthy People 2020. 4. Discuss the multidimensional nature of wellness. 5. Explain wellness in the context of chronic illness. 6. Identify recommended health promotion and disease prevention strategies for older adults. 7. Describe the role of the nurse in enhancing the health of older people. The emergence of a strong holistic health movement has refocused on a clear definition and operational approach to health and wellness. The holistic approach has long been in existence but has received little attention. Dunn (1961) saw health in a holistic context and defined it as an integrated method of functioning that is oriented toward maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable within the environment in which he or she is functioning. The holistic definition does not limit health to just its physical or mental or even social aspects but, rather, incorporates all of these facets in the total picture. This broader definition of health is particularly important in discussing the health of older people who may have multiple chronic conditions and be considered “ill” when looking through the lens of health-illness models. Consider the following: Wellness involves one’s whole being—physical, emotional, mental, social, spiritual, and environmental—all of which are vital components. For older people, health also includes the element of physical function. What is considered wellness to the individual must include his or her cultural orientation. Culture cannot be relegated to a subposition under any other health component. It must stand equally so that health care providers can realize and more adequately respond to the significance of culture in the attainment of well-being. Culture affects a person’s understanding of health as well as their health behaviors (Chapter 5). The wellness model refers to health as one aspect in the achievement of wellness. The wellness approach suggests that every person has an optimal level of functioning for each position on the wellness continuum to achieve a good and satisfactory existence (well-being) (Figure 2-1). Even in the presence of chronic illness or multiple disabilities or while dying, movement toward higher level wellness is possible if the emphasis of care is placed on the promotion of well-being in the least restrictive environment, with support and encouragement for the person to find meaning in the situation, whatever it is. The wellness continuum picks up where the traditional medical model leaves off. Instead of a downward negative trajectory for the health of the older adult, focused on deterioration, the wellness model rises and moves in a positive direction. The individual may reach plateaus in his or her ascension to higher level wellness. The wellness model encompasses the idea that health is a consequence of multiple determinants. Health determinants are the range of personal, social, economic, and environmental factors that determine the health status of individuals or populations. These include family, community, income, education, gender, race/ethnicity, place of residence, access to health care, and exposure to toxins, pollutants, and substandard housing. As stated in the Healthy People 2020 recommendations, this approach goes beyond the fundamentals of monitoring health behaviors such as diet and exercise and begins to connect different stages across the life span in terms of physical, emotional, and cognitive development. Health is a consequence of multiple determinants, which operate in nested genetic, biological, behavioral, social, and economic contexts that change as a person develops (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010a). Emotional wellness recognizes awareness and acceptance of one’s feelings as well as the ability to form interdependent relationships with others based on mutual commitment, trust, and respect. It includes the degree to which one feels positive and enthusiastic about oneself and one’s life and the ability to cope effectively with stress. Spiritual wellness recognizes the search for meaning and purpose in our lives and the taking of time to reflect and connect with the universe. Intellectual wellness includes expanding one’s knowledge and skills throughout life, discovering new skills and interests, and challenging oneself through creative, stimulating mental activities. Environmental wellness calls for caring for precious resources and creating living spaces and practices that respect and support the environment. Occupational wellness includes doing something that you love, contributing your unique gifts, skills, and talents to work that is personally meaningful and rewarding, and balancing work with leisure time. Social wellness recognizes the importance of staying engaged in meaningful activities and relationship and building a better world for current and future generations (Box 2-1; Hettler, 2010). Environmental wellness calls for caring for precious resources and creating living spaces and practices that respect and support the environment. In a concept analysis of healthy aging (Hansen-Kyle, 2005, p. 52), the following definition emerged: “Healthy aging is the process of slowing down, physically and cognitively, while resiliently adapting and compensating in order to optimally function and participate in all areas of one’s life (physical, cognitive, social, and spiritual).” The concept of healthy aging is a multidimensional process and is uniquely defined by each individual. For older adults being healthy is characterized by the way an individual feels in the context of existing illness or disability and the social and/or physical environment. Older adults have described being healthy as having four main components: functional independence, self-care management of illness, positive outlook, and personal growth and social contribution. As one older adult stated: “When you get into your 80s, little pieces of you kind of break off and fall astray … most of us have some little thing going on. And you know, we take care of that. …” (Miller and Iris, 2002, p. 255). The interrelationship of the facets that compose successful healthy aging are similar to the dimensions of wellness (Figure 2-2). Each aspect is like a petal, anchored to the center and overlapping the other petals, each affecting the whole. Alterations in or loss of a petal can change the overall effect or appearance and its wholeness. The conviction by nurses and other caregivers that older people are individuals with declining health generates responses that include treating the older person as ill and feeble, or potentially so. It is therefore expected by some that attempts to reverse conditions or situations, maintain a level of ability, or institute preventive health measures are useless for older people. Nothing could be further from the truth; all old people are improvable (Bortz, 1991). Historically, the principles of disease prevention and health promotion have not been aggressively applied to the problems of older adults. The focus has been on managing illnesses rather than on reducing risks, maintaining optimal function, and decreasing disability associated with illness. Healthy aging can no longer be viewed by looking only at older adults. The likelihood of a longer, more functional old age begins in the prenatal period and continues throughout life with health promotion efforts and appropriate clinical care. As Barondess (2008) states: “To a substantial degree, the health of the emergent adult is in the hands of the pediatrician” (p. 147). Exciting research in the field of epigenetics is leading to new understanding of the effect of environmental factors and lifestyle habits such as diet, stress, smoking, and prenatal nutrition on life expectancy for individuals and their children (see http://www.epigenome.org/ for more information). Recommendations for the framework of Healthy People 2020 recognize this and include attention to the effect of early life factors, together with later life factors, on health outcomes. Overarching goals of healthy people 2020 are presented in Box 2-2. Older adults have been added as a new topic area in HP 2020 with the goal of improving health, function, and quality of life. Emerging issues identified in the health of older adults include efforts to coordinate care, help older adults manage their own care, establish quality measures, identify minimum levels of training for people who care for older adults, and research and analyze appropriate training to equip providers with the tools they need to meet the needs of older adults. Other new additions to HP 2020 that are relevant to the health of older adults include dementias, sleep health, health-related quality of life and well-being, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health (see chapters 11, 19, 21, 22). A summary of HP 2020 objectives for older adults is presented in Box 2-3. In 2008, 39% of noninstitutionalized older persons rated their health as excellent or very good (compared with 60.7% for all persons aged 18 and older). There were few differences between the sexes, but ethnically and diverse older people were less likely to rate their health as excellent or very good than were older white people (Figure 2-3). The current generation of older people is generally healthier than earlier cohorts, and rates of disability are declining or stabilizing (Manton et al., 2008). Future cohorts of older people may be healthier and more functional well into their 80s and 90s. Fries’s (1980,1990) concept of compression of morbidity proposes that premature death will be minimized, and disease and functional decline will be compressed into a period of 3 to 5 years before death. There is some evidence that this is already occurring because major diseases such as arthritis, arteriosclerosis, and respiratory problems now appear 10 to 25 years later than for past cohorts (Fries, 2002; Hooyman and Kiyak, 2011). However, rates of disability and chronic illness continue to be higher among racially and ethnically diverse older adults and need continued attention (Hooyman and Kiyak, 2011). For example, American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN) “appear to be experiencing expansion of morbidity rather then compression. Among other health needs, more than one in five AI/AN elders have diabetes and this population experience higher rates of physical disability than age-matched White counterparts” (Goins et al, 2010, p. 1340). Further, some research suggests that overweight and obesity in adults aged 60-69, and among younger people, may have the potential to reverse declining disability rates. Obesity among U.S. adults has risen from 11% to 16% in the early 1960s to 28% to 34% in 2000. Levels of obesity are projected to be as high as 45.4% within 20 years (Seeman et al., 2010) (Chapter 14). The incidence of chronic illness increases with age. More than 80% of people over the age of 70 experience at least one chronic condition and 50% have multiple health problems. Some are relatively minor and do not significantly affect function whereas others can cause pain and disability. Heart disease, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, and diabetes are the most prevalent chronic illnesses in the older adult population. Prevention and management of chronic illness are a priority for all health care professionals and are receiving increased attention in the development of new models of care as well as research. Chapter 15 discusses chronic illness among older adults in more depth.

Health and Wellness

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Wellness

Dimensions of Wellness

Healthy Aging

Health Status of Older People

Self-reported Health

Disability and Chronic Illness

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Health and Wellness

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access