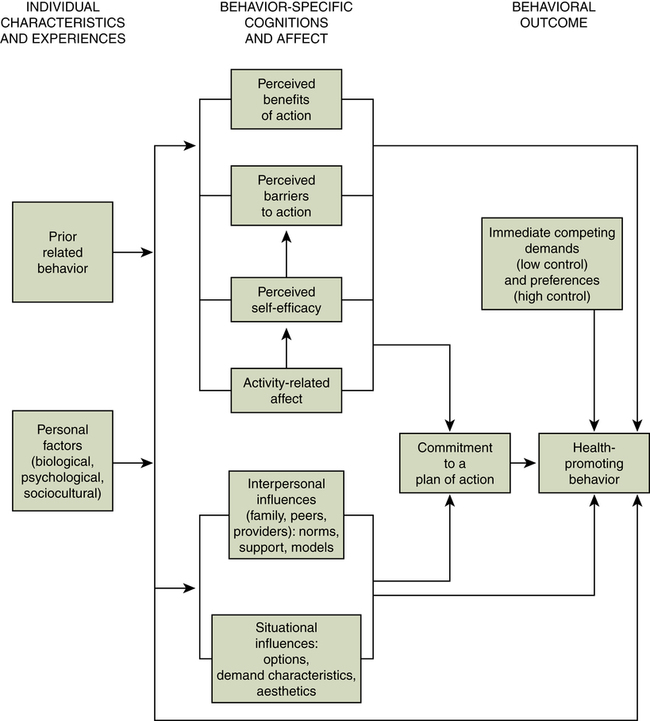

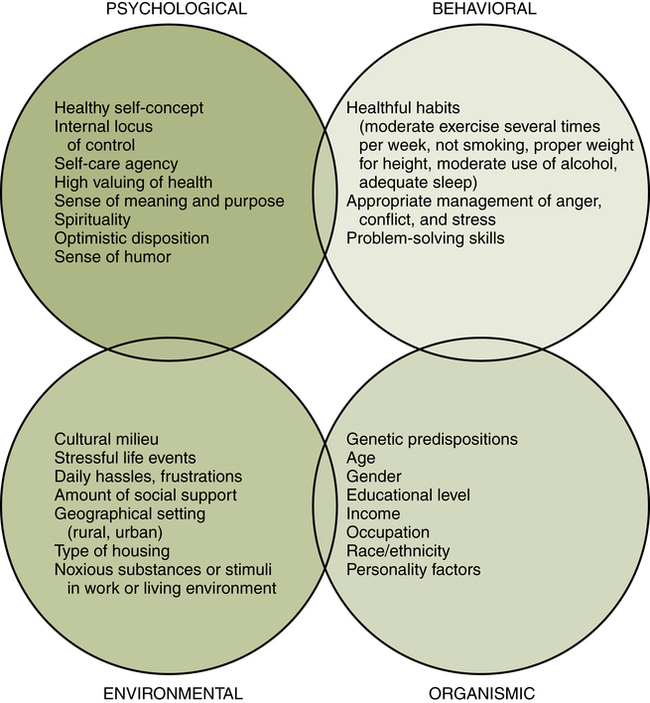

Sandra P. Thomas, PhD, RN, FAAN At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Compare several definitions and models of health. • Compare several models of health behavior. • Describe psychological, behavioral, and environmental factors related to wellness. • Apply the stages of change model to a selected health behavior. • Apply the health belief model to a selected health behavior. • Describe the use of evidence-based interventions to promote behavior change. • Describe the goals of Healthy People 2010. • Compare several types of community-level health promotion programs. Many Americans share Ricky’s longing for an easy way to lose weight or become fit. Millions of dollars are spent on books, tapes, pills, and exercise machines. But the outcomes Ricky seeks are not easy to achieve. Changing health behavior is difficult. Nurses, such as the family nurse practitioner profiled above, know how difficult it is to motivate well people to undertake behaviors that lessen the likelihood of future illness. Some health professionals have a mistaken notion that the mere provision of didactic information will bring about health-promoting actions. But studies show that although individuals are often aware of the risks associated with behaviors such as alcohol use and smoking, they modify their thinking about these risks rather than taking the more difficult route of changing the behaviors (Leffingwell, Neumann, Leedy, & Babitzke, 2007). Information is the solution only when ignorance is the problem. Health care providers need a more sophisticated understanding of the principles of behavior change to help their patients make health-promoting decisions. This chapter explores a variety of evidence-based interventions to change health behavior. Before discussing specific health behaviors, it is important to define health, a concept that remains something of an enigma. Is health a state, a process, or a goal? Gadamer (1996) pointed out that health “is not something that is revealed through investigation but rather something that manifests itself precisely by virtue of escaping our attention” (p. 96). To the average layperson, it is illness that compels attention, a departure from taken-for-granted smooth functioning. Likewise, traditional medical and nursing curricula have prepared health professionals to care for the acutely ill. Many textbooks still place greater emphasis on morbidity and mortality than on health promotion. In contemporary nursing literature, many authors assert that nursing has a mandate to promote holistic health. What does this mean? Unfortunately, some people think that holistic means “new age” or “alternative,” something outside traditional beliefs or practices. Because the term is frequently misused, it may be useful to trace its origin. The word holism was first used in a 1926 book by Jan Smuts (p. 99), the first prime minister of South Africa and a lifelong student of biological evolution. Smuts rejected the mechanistic explanation of the world that was pervasive in his time. He saw physical matter and the mind as inseparable, and he believed that holism, a dynamic striving toward integration, was the ultimate principle of the universe. Not until the late 1950s and 1960s did these ideas begin to infiltrate the American health care delivery system. In medicine, Halbert Dunn began to speak of “high level wellness,” the ultimate integration of body, mind, and spirit as an interdependent whole (1959, 1971). In nursing, Martha Rogers (1970) wrote about unitary human beings who are not reducible to parts or symptoms. She also emphasized the indivisible whole of person and environment. Concurrent with the gradually shifting perspective of health professionals, a consumer wellness movement burgeoned that was linked to the other human liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s such as the civil rights and women’s movements. Public dissatisfaction with paternalistic medical treatment and mystifying medical terms, along with a better educated, more affluent populace, contributed to a thirst for information about holistic therapies and self-care. Americans became preoccupied with self-care clinics, self-help groups, and the tantalizing potential of peak wellness and self-actualization. One prominent nursing theorist, Dorothea Orem, began to emphasize patients’ self-care agency, recommending nursing intervention only when a self-care deficit is detected (1983). Education of the public for self-care became an important element of federal government policies and public health initiatives, such as the Healthy People initiative, first begun in 1979 and reformulated each succeeding decade. Motivated by escalating costs of care for sick workers, corporations began to demand that employees assume more responsibility for their health and provided them incentives such as exercise rooms, walking trails, and low-fat meal options in the employee cafeteria. Several of the nursing theorists noted here and elsewhere in this chapter are also discussed in Chapter 5. Nursing interventions to promote health are guided by ideas about human beings and the meaning of the concept of health. Smith (1983) traced evolving conceptions of health across the centuries, categorizing them into four models (Table 15-1). TABLE 15-1 Modified from Smith, J. (1983). The idea of health: Implications for the nursing profession. New York: Teachers College Press. The role performance model depicts health as the ability to fulfill one’s customary social roles. Thus if a young mother is able to adequately carry out her childcare activities, she would be deemed healthy. If she cannot perform these activities, she would be considered ill. The problem with this view of health is the distressful and stultifying nature of many people’s occupational or familial roles. Scholars are now placing emphasis on the quality of experience in social roles and the degree of choice about occupancy of these roles (Thomas, 1997a). Can individuals trapped in unsatisfying jobs or marriages achieve optimal health? What is the health impact of juggling multiple roles or experiencing role conflict? What if performance in one role (worker, for example) so dominates one’s existence that performance in another role (parent) is compromised? Based largely on the ideas of Dubos (1965), the adaptive model emphasizes the ability to adapt flexibly to ever-changing environments and challenges. Continuous readjustment to life’s stressful demands is necessary. Healthy people are resilient and hardy. Disease is viewed as a failure of adaptation. Although the adaptive model achieved popularity in nursing, as exemplified in the work of theorists such as Callista Roy (1970), there is a still broader conceptualization of health. Drawn from the Greek philosophers and from the humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow (1961), the eudaemonistic model depicts health as the complete development of the individual’s potential, an exuberant well-being. Clearly, this model emphasizes the human capacity for growth. Within nursing, theorist Margaret Newman (1978, 1994) has proposed that health is expanding consciousness. For this chapter, a broad concept of health was selected, consistent with the broader view exemplified in Smith’s adaptive and eudaemonistic models and Dunn’s description of high-level wellness. Adopting a broader view of health has several implications for nursing practice. For one thing, separating mind, body, and spirit becomes impossible. Moreover, the patient’s embeddedness in family, friendships, culture, and the environment cannot be ignored. Also, the patient’s own power for healing is recognized. The role of the nurse is that of facilitator of the patient’s own innate capabilities for healing and growth. Skilled counseling is as important as technical competence. Chapter 4 discusses roles in more detail. The terms health promotion and disease prevention, although often used synonymously, actually have different meanings. Flowing logically from adaptive or eudaemonistic views of health, health promotion refers to activities that protect good health and take people beyond their present level of wellness. By achieving lean and fit bodies and well-managed stress levels, individuals have a greater likelihood of achieving a high quality of life and reaching the goal of self-actualization. In contrast, disease prevention efforts are derived from the clinical model of health. Emphasis is frequently placed on avoidance, deprivation, or restraint. Behaviors are undertaken to prevent specific diseases. The importance of preventive efforts becomes obvious when reviewing statistics showing that men lose the equivalent of 11.5 well-years of life and women lose the equivalent of 15.6 well-years from morbidity (Kaplan, Anderson, & Wingard, 1991). Mortality statistics likewise demonstrate the importance of lifestyle modifications to prevent premature death. The chief causes of death in the United States are strongly related to unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and overeating (Box 15-1). Convincing empirical evidence shows that healthy lifestyles can significantly reduce the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, obesity, diabetes, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Therefore the modification of health attitudes and behavior is one of the most important responsibilities of every nurse. As shown in Figure 15-1, a comprehensive model of wellness includes interacting factors such as psychological characteristics, health-promoting behaviors, and aspects of the environments in which people live and work. Both attitudes and behaviors are modifiable by health care providers, as well as some (but not all) aspects of environments. The sections that follow examine a number of these modifiable factors. Although a comprehensive wellness model includes organismic variables (e.g., genetic predispositions) and demographic characteristics (e.g., age, income, gender), these are not amenable to modification by health care providers. We instead emphasize the factors that can be affected by nurses. Locus of control is a construct from Rotter’s (1954) social learning theory. According to this theory, as individuals are exposed to reinforcements (rewards) for their behavior, they develop beliefs about their ability to control desired outcomes or rewards. Eventually, most people have a stable, general expectancy that reinforcements are contingent on their own behavior (termed internal locus of control) or an expectancy that rewards are received on a purely random basis or dispensed by powerful others (called external locus of control). This stable, general expectancy has been given a variety of other names by researchers. For example, locus of control is subsumed in Kobasa’s (1979) multidimensional hardiness construct and Antonovsky’s (1984) sense of coherence. What does locus of control have to do with wellness? Rotter’s theory was modified for health by researchers such as Wallston (1989). Logically, individuals who have an internal locus of control are more likely to engage in positive health behaviors. They believe that the reinforcement (good health) is directly related to their own actions, not controlled by powerful others (e.g., doctors) or by the vicissitudes of fate. Although questionnaires are available to measure locus of control, a nurse can easily assess it by asking questions such as the following: “What do you think caused you to have this heart attack? Who do you think knows best what you really need? Do you normally follow instructions pretty well, or do you prefer to work things out your own way?” Nursing interventions can be tailored accordingly. If the person has an internal locus of control, a nurse should allow a high degree of client participation in goal setting and selection of reinforcers. If the person has an external locus of control, providing plenty of concrete guidance and support is important. For example, if the goal is weight loss, suggest involvement in a program with regular group meetings, such as Weight Watchers. Self-care agency, a term coined by nurse theorist Dorothea Orem (1995), refers to the ability to care for oneself, for which the person must have knowledge, skills, understanding, and willingness. In working with a client, assessment of all these factors is necessary. A parallel concept from social cognitive theory called self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997) has generated a sizable body of health psychology and nursing literature. According to Bandura’s theory, when people perceive that they have efficacy to accomplish a specific behavior (e.g., breast self-examination), they are predisposed to undertake the behavior. Studies of older adults found that self-efficacy significantly influenced exercise behavior (McAuley et al., 2008; Resnick & Spellbring, 2000). Other studies have established links between self-efficacy and weight management, smoking cessation, chronic disease management, and medication adherence (Anderson & Anderson, 2003). This empirical evidence suggests that a nurse’s first step in working with many clients is to enhance their belief in personal capability. Research shows that self-efficacy is modifiable through strategies such as anticipatory guidance and persuasive motivational messages (Bandura, 1997). Values are elements that show how a person has decided to use his or her life. Values serve as a basis for decisions and choices. The nurse must assess the reinforcement value of health to an individual compared with other life values such as pleasure, excitement, or social recognition. Jackson, Tucker, and Herman (2007) found that individuals who place a higher value on health also display greater involvement in a health-promoting lifestyle. Of course, some people declare that they highly value health, but their behaviors contradict this declaration. A value system may contain conflicting values. For example, highly valuing achievement and financial prosperity may result in overwork and neglect of health. Assisting a client to clarify conflicting values can be a useful intervention. The chapter on ethics (Chapter 12) discusses values in more detail. Having a sense of meaning and purpose for one’s life may be an important factor in individuals’ responsiveness to health providers’ instructions. Purpose in life includes having goals for the future and a sense of directedness. Exploring whether clients aim to follow a particular career trajectory, pursue an enjoyable hobby or avocation, or see their children and grandchildren grow and mature is often helpful. In what way does each person aim to make a difference or leave a legacy? Persons with clear goals may devote more effort to health maintenance because most goals cannot be achieved without good health. Empirical evidence shows that purpose in life is correlated with good health habits (Williams, Thomas, Young, Jozwiak, & Hector, 1991). Health researchers and clinicians are increasingly recognizing that spirituality is an integral component of holistic health and wellness. Spirituality is not synonymous with involvement in organized religion, but the sense of connection with a divine wisdom or higher power often motivates practices such as meditation, prayer, and attendance at religious services. Studies have examined the relationship of spirituality and/or religious practice with disease conditions (e.g., heart disease, cancer, mental illness) as well as health risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking, using drugs) (Hart, 2008). Rapidly burgeoning research shows that religious people are less anxious and depressed and are more adept at coping with illness and tragedy than are nonreligious individuals (Koenig, cited in Paul, 2005). Clients may be motivated to take health-promoting actions by a belief that the body is a temple for the spirit. An optimistic disposition has been shown to be important to health in studies conducted for more than two decades. Carver and Scheier (2002) assert that optimism is a stable personality characteristic with important implications for the manner in which people regulate their actions, particularly actions relevant to health. The construct of optimism includes tendencies to expect the best, look on the bright side, and anticipate good things in the future. It is important to note that the presence of optimism is not dependent on a person’s particular locus of control; expectations of favorable outcomes could be derived from perceptions of being lucky or blessed (external locus of control) or from convictions of personal control (internal locus of control). Higher levels of optimism have been associated with positive health outcomes such as completion of an alcohol treatment program and faster recovery after coronary bypass surgery, bone marrow transplant, and traumatic injury (Carver & Scheier, 2002). An optimistic outlook can be cultivated if it does not come naturally (Seligman, 1998). Although a sense of humor is a socially appealing trait, it also conveys health benefits. The physical effects of mirth have been compared with the effects of exercise. For example, laughing 100 times expends the same number of calories as 10 minutes on a rowing machine (Godfrey, 2004). The efficiency of the respiratory system increases, and the cardiovascular and muscular systems relax (Kennedy, 1995). Humor and laughter have been linked to higher levels of endorphins and immunoglobulin A and lower levels of cortisol (Berk et al., 1989; Godfrey, 2004). Laughter is an excellent way to dispel stress and tension as well. Perhaps that is why laughter clubs quickly became popular across the globe after an Indian physician started the first one in 1995 (Perry, 2005). Behaviors associated with wellness are listed in Figure 15-1. The first research about health behaviors was done in the 1950s by social psychologists who sought to explain the public’s perplexingly low response to screening programs that were free or low in cost (Hochbaum, 1958). From this work, a model emerged that can be used to predict preventive health action. According to the health belief model (HBM), an individual’s perceptions of his or her susceptibility to a disease (and the severity of that disease), the perceived benefits of taking action, and cues to action (from media, health professionals, or family) contribute to the likelihood of taking preventive actions—provided that barriers are not too great (Becker et al., 1977). Subsequent research with the HBM found barriers to be the most useful element of the model in predicting behavior such as physical exercise (Janz & Becker, 1984). Typical barriers are time, expense, and inconvenience. In the 1980s, nurse researcher Nola Pender presented a model with similarities to the HBM but with greater emphasis on health-promoting behaviors. Based on research that tested Pender’s Health Promotion Model, the model was revised, deleting constructs with insufficient predictive power (Figure 15-2). Individual characteristics and prior behavior are theorized to affect perceptions of self-efficacy, benefits and barriers to action, and a variable called “activity-related affect,” which refers to the feelings about the behavior in question. For example, is exercise fun or unpleasant? All these factors, as well as interpersonal and situational variables, can influence commitment to a plan of action. Additionally, competing demands such as work or family care responsibilities are taken into account in the prediction of health-promoting behavior, the outcome variable of the model. The best predictors of health-promoting behavior, according to a synopsis of 38 studies, are perceived self-efficacy, perceived barriers, and prior behavior (Pender, Murdaugh, & Parsons, 2002). Most health behavior models fail to acknowledge the powerful role of affect. Lawton, Conner, and McEachan (2009) found that affect (the enjoyment of the activity) was a better predictor than cognitive attitude (harm or benefit of the activity) for four risky behaviors (e.g., drinking) and five health-promoting behaviors (e.g., eating fruits and vegetables). The researchers concluded that “many of the behaviors that most threaten our health and safety may not be reasoned or planned but depend, at least to some extent, on whether they make us feel happy or sad, relaxed or tense” (Lawton et al., 2009, pp. 63–64). More than 30 years ago, longitudinal studies established that good health habits, such as regular exercise, are correlated with better health status and longevity (Belloc & Breslow, 1972; Breslow & Enstrom, 1980). Given that the benefits of healthful habits are well established, the average American’s lack of adherence to the recommended lifestyle regimen is discouraging. We focus here on exercise, diet, tobacco use, sleep, and emotion management. Most adults (75%) do not engage in 30 minutes of daily exercise, and one third are completely sedentary (Physical activity trends—United States, 2001). Sedentarism has increased in both children and adults with the escalation of hours spent using computers, television, and hand-held electronic devices for entertainment as well as business purposes (Ricciardi, 2005). The prevalence of inactivity rises with age, and women are more likely than men to be inactive at all ages (Wang, Pratt, Macera, Zheng, & Heath, 2004). Analyzing data from a nationally representative sample, researchers found a strong relationship between inactivity and cardiovascular disease, resulting in medical expenses of more than $23 billion dollars (Wang et al., 2004). Even when an exercise program is started, the usual rate of dropout is 50% in the first 3 to 6 months (Pender, 1996). Many people have an aversion to exercise, mentally associating it with competitive sports or regimented calisthenics. Even as health club membership climbs—at least among the more affluent—too many Americans pay someone else to wash the car, use riding mowers to mow the lawn, and treat their treadmills as clothes racks. Nurses need to spread the word that gym membership and expensive equipment are not necessary for regular physical workouts. Research shows that long-term adherence to an exercise program is more likely when the regimen is home based rather than dependent on participation in a group class at a gym (King et al., 1997). If finances preclude purchasing a set of weights, soup cans and other household items can be substituted. Although fear of crime inhibits outdoor exercise, especially among women and older adults (Roman & Chalfin, 2008), nearly everyone can find some safe place to walk (shopping malls are a good alternative for those who live in unsafe neighborhoods). Studies show that walking provides almost all the benefits of more vigorous activity, requires no equipment or fees, and can be done alone or with a companion (Norman & Mills, 2004). Gardening, dancing, and biking are pleasurable activities that are also beneficial to the heart and muscle tone. A person raking leaves burns 288 calories per hour—while also enjoying fresh air and fall colors. Clients may be more motivated to exercise when informed of immediate benefits, such as increased energy and improved mood. Exercise can lift spirits for as long as 2 to 4 hours (Kaplan, 1997). Because so many clients are completely sedentary, professionals must remember to begin with realistic and achievable goals, such as 5 to 10 minutes of walking. In an experiment with healthy young college women, aimed at enhancing their exercise self-efficacy, some women dropped out of the study at the time of the pretest because they perceived that a “step test” was frightening and aversive. They were afraid that the subsequent exercise sessions (step aerobics, dancing, and kickboxing) would be far too difficult for them to perform (D’Alonzo, Stevenson, & Davis, 2004). If such apprehensions are present in healthy young women, consider how they could be magnified in older adults. Effective exercise interventions must be tailored carefully. On a positive note, emphasize to clients that as little as 10 minutes a day of moderate exercise can reduce risk for disease and improve quality of life (Listfield, 2009). The United States is in the midst of an alarming obesity epidemic, in which more than one third of adults are obese (Ogden, Carroll, McDowell, & Flegal, 2007). Not only is obesity (a body mass index greater than 30) rapidly rising, but so is morbid obesity (defined as a BMI greater than 40). Between 2000 and 2005, the number of individuals with a BMI greater than 40 increased by 50% (and those with a BMI greater than 50 increased by 75%) (Sturm, 2007). By 2030, the global burden of obesity will be staggering: 2.16 billion adults are predicted to be overweight and 1.12 billion obese (Kelly, Yang, Chen, Reynolds, & He, 2008). Childhood obesity has reached such unparalleled proportions that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a $60 million prevention program (Holloway, 2005). It is clear that the “happy meals” children consume today will have unhappy consequences for their health tomorrow. The prevalence of obesity in school-age children has quadrupled since the 1970s (Estabrooks, Fisher, & Hayman, 2008), and an obese child has a 70% to 75% chance of becoming an obese adult (Clarke & Lauer, 1993). Some obese children already have the arteries of 45-year-old adults. Among the consequences of the rapidly rising incidence of obesity in the United States is the increased number of adults with hypertension (65 million now compared with 50 million in 1994). Millions more are prehypertensive (Kluger, 2004), prompting the government to recommend the low-fat, low-salt, low-sweets DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension). Despite widespread media promotion of the USDA’s Food Guide Pyramid (MyPyramid) and the plant-based Mediterranean diet, Americans consume nowhere near the recommended daily servings of fruits and vegetables. Current intake of flour, grains, and beans is only two thirds of what society consumed in 1910. Each person, on average, consumes 150 pounds of sweeteners (mostly sugar and corn syrup) per year, 25 pounds more than in 1984. Americans drink twice as much carbonated soda as milk. And society still consumes too much fat (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2008). Falling consumption of fish is another problem, resulting in inadequate intake of omega-3 fatty acids, which could reduce heart attack risk (Campos, Baylin, & Willett, 2008) and improve mood and mental health (Hallahan & Garland, 2005). Human beings are not genetically adapted for this type of diet. In fact, people should be eating like hunter-gatherers, who had no atherosclerosis even when they lived to advanced ages (Cordain, Eaton, Brand Miller, Mann, & Hill, 2002). This would mean replacing carbohydrates (especially foods with a high glycemic index, such as bread and potatoes) with proteins. Food is laden with emotional and social significance, complicating attempts at dietary modification. Therefore targeting interventions to children while their eating habits are still developing makes good sense. When she learned that one third of school-age children in her state were overweight or obese, the Texas agriculture commissioner (a mother of three) banned junk food from school cafeterias (Booth-Thomas, 2004). Grain bars, nuts, and baked chips replaced candy in the school vending machines. Fresh produce, yogurt, and low-sugar drinks became available to the students. Nurses could become involved in similar efforts to combat childhood obesity in their own communities. Complicating nurses’ efforts to combat the obesity epidemic is their own predilection to be overweight or obese; more than half of nurses weigh too much (Miller, Alpert, & Cross, 2008). Research shows that laypersons have less confidence in nurses’ ability to provide health education when nurses themselves are overweight (Hicks et al., 2008). According to the World Health Organization, 20% of the world’s people smoke; in 2008 smoking killed more than 5 million people (WHO, 2008). In the United States, public smoking has been discouraged by bans in offices, restaurants, and airports. Many Americans have kicked the habit. But smoking prevalence remains high among lower-income groups, and it is rising among girls and women, with a concomitant increase in female lung cancer. Another disturbing trend is waterpipe (hookah) smoking, which is becoming popular among college students because of the pleasant flavorings (e.g., apple, coffee) and sweeteners added to the tobacco (Primack et al., 2008). Approximately 90% of new smokers are teenagers; 3000 begin smoking every day (Lindell & Reinke, 1999). More adolescents are smoking today than at any time since the 1970s. Some 35% of today’s high school students smoke cigarettes, compared with 28% in 1991 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996). Some youngsters have their first smoke in middle school or earlier. These youngsters do not know they are exposed to more than 4000 chemicals each time they light up, including arsenic and radioactive compounds such as polonium (Ruppert, 1999). Some of them have the mistaken belief that waterpipes, cigars, clove cigarettes, or chewing tobacco are healthy alternatives to cigarettes. The statistics on youth tobacco use are deeply disturbing given the addictive potential of nicotine. In addition, adolescent smoking is a powerful predictor of adult smoking (Chassin, Presson, Rose, & Sherman, 1996). Studies have shown that nurse-delivered smoking cessation counseling is effective even when relatively brief; only a few minutes are necessary for a nurse to ask about smoking status, assess a client’s desire to quit, and provide evidence-based advice about tactics (Bialous & Sarna, 2004). Approximately 76% of smokers say they want to quit, but they lack specific plans to do so (Herzog & Blagg, 2007). There are many barriers to quitting: withdrawal symptoms, missing the companionship of cigarettes, less control of stress and moods, fear of weight gain, and lack of encouragement from family and friends. Some of the barriers can be dispelled by clear, strong, and personalized advice from clinicians: “Continuing to smoke makes your asthma worse” or “Quitting smoking may reduce the number of ear infections your child has” (Fiore et al., 2008, p. 163). Some parents are surprised to learn that their children are still exposed to the toxins in tobacco smoke even if the parent smokes only while the children are sleeping. “Third-hand smoke” lingers in the home, contaminating surfaces where children crawl and play (Third-Hand Smoke: Another Reason to Quit Smoking, 2008). Motivating a client to stop smoking is always a challenge. James Prochaska and his research team have studied the stages of change in addictive behaviors (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). In working with a client, the Prochaska model is helpful in assessing the client’s stage. The Prochaska model is applied to smoking cessation in Table 15-2. Health professionals can promote client movement to subsequent stages by interventions that raise consciousness. For example, a middle-age man in a high-stress job may be startled to learn that smoking does not improve mood on stressful days; smoking actually worsens mood (Aronson, Almeida, Stawski, Klein, & Kozlowski, 2008). An adolescent girl who uses smoking for weight control may consider cessation when she learns of its negative effects on the skin. Interventions to promote smoking cessation can be guided by the HBM, as shown in Table 15-3. Medication should be prescribed, unless contraindicated; nicotine replacement therapy combats withdrawal symptoms such as irritability and craving. Research by Judith Prochaska’s team showed that exercise during smoking cessation not only improves mood but also increases the probability of staying smoke-free (Prochaska et al., 2008). During cessation, smokers must break the associations between smoking and familiar environments (e.g., the living room couch) that stimulate craving (Stambor, 2006), so alterations in the environment and daily routines are recommended. Lapses in abstinence are common, and clients must be encouraged to resume the strategies that initially helped them to quit. Successful quitters usually make several tries. TABLE 15-2 Prochaska’s Transtheoretical Model of Change Applied to Smoking Cessation Modified from Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102–1114.

Health and Health Promotion

![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() Concept of Health

Concept of Health

![]() Evolving Conceptions of Health

Evolving Conceptions of Health

Model

Conception of Health

Clinical

Elimination of disease as identified through medical science

Role performance

Ability to perform social, occupational, and other roles

Adaptive

Ability to engage in effective interaction with environment

Eudaemonistic

Self-actualization of individual; optimal well-being

ROLE PERFORMANCE MODEL

ADAPTIVE MODEL

EUDAEMONISTIC MODEL

![]() Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

![]() Modification of Health Attitudes and Behaviors

Modification of Health Attitudes and Behaviors

PSYCHOLOGICAL ATTITUDES AND CHARACTERISTICS ASSOCIATED WITH WELLNESS

Self-Concept

Locus of Control

Self-Care Agency

Values

Sense of Purpose

Spirituality

Optimism

Sense of Humor

HEALTH BEHAVIORS ASSOCIATED WITH WELLNESS

Health Habits

Exercise

Healthy Eating

Tobacco Use

Stage 1: Precontemplation

Smokers do not see their smoking as a problem and do not intend to stop within the next 6 months.

Stage 2: Contemplation

Smokers see their smoking as a problem and think about quitting but are not ready to change.

Stage 3: Preparation

Smokers intend to take action in the next month; some have made small changes, such as cutting down on the number smoked or delaying the first smoke of the day.

Stage 4: Action

Smokers adopt a goal of smoking cessation and make an attempt to quit, involving overt behavior change and environmental modification.

Stage 5: Maintenance

Smokers work to prevent relapse and maintain abstinence.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Health and Health Promotion

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access