Introduction

Haemorrhage may be defined as blood loss sufficient to cause haemodynamic instability (American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), 2004).

Heavy bleeding in the antenatal, intrapartum or immediate post-delivery period can become a serious emergency requiring rapid action. It is a comparatively common occurrence, and every midwife will face at least one serious haemorrhage at some time in his/her career. It can be terrifying for a woman and her partner (Mapp & Hudson, 2005). Timely and methodical management usually resolves the situation, but occasionally the haemorrhage can be catastrophic, even leading to death (CEMACH, 2004).

Incidence and facts

- The death rate from haemorrhage is approximately 6.5/million maternities (CEMACH, 2004). The 2004 Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths (CEMACH) report cites 17 deaths directly due to haemorrhage.

- Haemorrhage can occur prior to, during or following birth; it can be dramatic and sudden or slow and incipient. Slow, continuous bleeding often goes unnoticed, but may still lead to maternal death (AAFP, 2004).

- Accurate visual estimation of blood loss is known to facilitate timely resuscitation (Bose et al., 2006). Blood loss >300 ml is often underestimated, with greater inaccuracy as volume increases (World Health Organization (WHO), 2006).

- Higher-risk groups include women with placenta praevia (especially those with a previous caesarean or myomectomy scar), uterine fibroids, placental abruption or previous third-stage complications (CEMACH, 2004). A woman’s risk of haemorrhage should be assessed antenatally by the midwife. Women with increased risk should be advised to have their babies in a consultant unit with an on-site blood bank (CEMACH, 2004).

- Each unit should have a multidisciplinary massive haemorrhage protocol and regularly rehearsed drills (CEMACH, 2004; Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST), 2006). Practical sessions with real blood spillages may improve blood loss estimation (Bose et al., 2006).

- The principles of haemorrhage management are the same whatever the setting, but early intervention is particularly important at home or birthing centres (see Chapter 6). On transfer give concise information to receiving clinicians as to the emergency encountered.

Placenta praevia

Placenta praevia is the abnormal implantation of the placenta in the lower uterine segment, with partial or complete coverage of the cervical os. Haemorrhage is a significant risk. Incidence rises in the third trimester with the development of the lower segment and uterine contractions.

Incidence and facts

- 0.5% of pregnancies (AAFP, 2004) of which 15% of placenta praevia are complicated by placenta accreta (McDonald, 1999).

- Four maternal deaths were cited as due to placenta praevia in the 2004 CEMACH report.

- The only safe mode of delivery for complete placenta praevia is by caesarean section (CS) as the os will be obstructed (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), 2005).

- All women with placenta praevia and their partners should have antenatal discussions regarding delivery, haemorrhage and possible blood transfusion, even hysterectomy (RCOG, 2005), and their views sensitively managed.

- Placenta praevia is more common in women with a uterine scar (RCOG, 2005), previous uterine surgery (AAFP, 2004) and in multiparity (McDonald, 1999).

- Both an obstetric and an anaesthetic consultant should be available as a CS hysterectomy may become necessary due to uncontrollable haemorrhage (CEMACH, 2004). Admission is advisable when repeated bleeding occurs (CEMACH, 2002; RCOG, 2005).

- Autologous blood donation (Dinsmoor & Hogg, 1995) or intra-operative blood cell salvage if available (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), (2005)may be options for women declining transfusion. Alternative arrangements should preferably be discussed antenatally (CEMACH, 2004).

For diagnosis of placenta praevia see (Table 15.1) and for care of a woman with placenta praevia see p. 208.

Placental abruption

Placental abruption is the partial or total separation of the placenta from the uterus during pregnancy or labour. It is a major cause of perinatal mortality (McGeown, 2001).

Incidence and facts

- 1–2% of pregnancies (AAFP, 2004).

- 10% of stillbirths have been attributed to antepartum haemorrhage (CEMACH, 2006). The risk of stillbirth is proportionate to the degree of placental separation (AAFP, 2004).

- Three maternal deaths were attributed to placental abruption in the 2004 CEMACH report (CEMACH, 2004).

- Many cases are mild and the pregnancy uneventful. Severe cases require the co-ordinated care of obstetricians, midwives, anaesthetists and haematologists (McGeown, 2001).

- Abruption should be considered in any woman with abdominal pain, with or without bleeding (AAFP, 2004).

- For smaller bleeds facilitating vaginal delivery (with continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM)) and if necessary inducing/augmenting with intravenous (IV) oxytocin) may reduce the CS rate by 50% without effecting perinatal mortality (Fraser & Watson, 2000).

- Symptoms of shock are a late sign and represent a blood loss of >30% of blood volume (AAFP, 2004).

- One-third of women with abruption and fetal demise will develop coagulopathy as thromboplastins from the placental site are released, potentially activating the clotting cascade (AAFP, 2004). Consumptive coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy may follow (AAFP, 2004).

Risk factors for placental abruption

- Hypertension in 25–50% of cases (Lockwood, 1996).

- Abdominal trauma, e.g. domestic violence and road traffic incidents (AAFP, 2004).

- High parity and advanced maternal age (AAFP, 2004).

- Growth restriction (Ananth & Wilcox, 2001).

- Uterine overdistension: polyhydramnios and multiple gestation (AAFP, 2004).

- Smoking (AAFP, 2004) and some substance abuse (Miller et al., 1995).

- Some thrombophilias (McGeown, 2001).

Care of a woman with placenta praevia/placental abruption

For diagnosis see (Table 15.1)

With severe placenta praevia, CS delivery is likely. Abruption/low-grade placenta praevia may be managed expectantly if bleeding is mild to moderate, is settling (AAFP, 2004) and/or the baby is very preterm and the mother is stable (Fraser & Watson, 2000).

- Assess and record blood loss.

- Note location of abdominal tenderness. It may relate to placental site, back pain associated with posterior placenta (AAFP, 2004).

- Monitor vital signs. Tachycardia > 90 bpm with systolic BP < 100 mm Hg and/or diastolic < 50 mm Hg may indicate impending hypovolaemic shock (WHO, 2003).

Table 15.1 Diagnosis of placenta praevia and placental abruption.

| Placenta praevia | Placental abruption | |

| Pain | Usually painless | Varies from mild to severe Uterine pain or back pain if placenta posterior or concealed abruption (AAFP, 2004) |

| Uterus | Soft/usually relaxed 25% experience variable strength contractions (Lockwood, 1996) | Tense/tender Hypertonus generally seen in severe cases when the baby has died and with concealed abruption (AAFP, 2004) |

| Bleeding | Usually visible (AAFP, 2004) | Usually visible but 20% present with concealed bleeding (Frazer & Watson, 2000; AAFP, 2004) |

| Symptoms of shock (see p. 235) | May be present | May be present |

| Baby | Commonly non-engaged, ballotable presenting part 35% present as unstable lie (Lockwood, 1996) | Usually normal lie and presentation |

| Vaginal examination | Contraindicated: may exacerbate bleeding (Frazer & Watson, 2000) | Not contraindicated |

| Ultrasound scan (US) | Review US reports for placental location and fetal gestation.Transvaginal US may confirm placental edge (AAFP, 2004). Magnetic resonance imaging may enhance placental image quality (RCOG, 2005) | Ultrasound scan to exclude placenta praevia. Differentiation between fresh bleeding and placental tissue can be difficult as haematomas become hypoechoic after a week (Nyberg, 1987) |

- Perform EFM (AAFP, 2004). A non-reassuring fetal heart rate may indicate the need to expedite delivery due to the significant risk of fetal demise (AAFP, 2004) (see the Appendix in Chapter 3).

- Palpate/monitor contractions. Abruption may cause a high resting tone and superimposed small frequent contractions (AAFP, 2004).

- Site large gauge IV cannula. Check full blood count and blood group. If bleeding persists give IV fluids. Maintain a fluid balance chart.

- Ensure cross-matched blood (4 units) is ordered.

- Consider clotting studies as disseminated intravascular coagulopathy may develop (AAFP, 2004) fibrinogen levels, prothrombin time/international normalised ratio/activated partial thromboplastin time.

- Consider Kleihauer testing if woman is rhesus negative (Crowther & Keirse, 2002) to detect fetal cells in the maternal circulation.

- Inform team: obstetrician, anaesthetist, paediatrician, neonatal intensive care unit and theatres. If condition serious inform the intensive care unit.

In labour

- Analgesia and support. Placental abruption can be very painful. Support, reassurance and analgesia are essential. Assist the woman to get comfortable, use bean bags/pillows, massage, touch and pharmacological analgesia.

- Monitor labour progress. Continue EFM throughout (AAFP, 2004), monitor contractions and document fluid balance, blood loss and maternal vital signs. Rapid intervention may be required.

- Give regular antacids/hydrogen ion inhibitors in anticipation of possible anaesthetic (RCOG, 2004).

- Expedite delivery if bleeding is heavy, ongoing or greater than infusion ability (AAFP, 2004). There is evidence of compromise to mother or baby (Hayashi, 2000) or labour is not progressing (AAFP, 2004).

- If haemorrhage continues

Site a second large gauge cannula.

Site a second large gauge cannula. A central venous pressure line may be sited to accurately monitor fluid volume.

A central venous pressure line may be sited to accurately monitor fluid volume. Record hourly urine volume via catheter. Output should be ≥30 ml/hour (AAFP, 2004).

Record hourly urine volume via catheter. Output should be ≥30 ml/hour (AAFP, 2004). Order blood urgently: platelet and fresh frozen plasma infusion may be required prior to operative delivery if coagulopathy is present (AAFP, 2004).

Order blood urgently: platelet and fresh frozen plasma infusion may be required prior to operative delivery if coagulopathy is present (AAFP, 2004).See also basic care for shock, Box 16.4, p. 235.

Third-stage management

- Delay cord clamping by ≥30 seconds if possible as the baby is at risk of anaemia (Mercer, 2001). Delayed clamping increases blood volume to the baby increasing the haemoglobin and haematocrit (Prendiville & Elbourne, 2000).

- Leave a long cord to enable umbilical cord catheterisation if required.

- Take paired cord blood samples for pH testing. If the motheris rhesusnegative, a direct Coombs’ test from umbilical cord blood may indicateantibodypresence; consequent haemolysis may cause neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia.

- Active management is recommended to reduce risk of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH).

- Have a syntocinon infusion ready in case of PPH.

- Remember that blood loss is frequently underestimated (WHO, 2006).

Postpartum haemorrhage

The World Health Organization defines PPH as 500 ml blood loss in first 24 hours postdelivery (WHO, 2003). However, any blood loss that causes the woman’s condition to deteriorate is considered a PPH (WHO, 2006). Early summoning of quality and senior help by the midwife can save valuable time and prevent a situation getting out of control.

Women who suffer a PPH usually find the experience frightening and traumatic. Remembering fear and pain may increase their anxiety in any subsequent birth. The woman’s birth partner may experience feelings of helplessness and concern manifested as quiet anxiety, asking many questions or occasionally showing panic or aggression.

Incidence and facts

- PPH occurs in 4% of vaginal deliveries (AAFP, 2004) and 4–8% of CS (RCOG, 2004).

- PPH has four causes, the 4Ts: Tone (uterine atony), Tissue, Trauma and, rarely, Thrombophilias (clotting problems). Incidence: 70% tone, 20% trauma, 10% tissue and 1% thrombin (AAFP, 2004).

- Life-threatening haemorrhage is estimated at 6.7 per 1000 deliveries (CEMACH, 2004), and it remains a major cause of death globally (AAFP, 2004).

- Ten maternal deaths occurred due to PPH in the 2004 CEMACH report, with two deaths of women who refused blood transfusion (CEMACH, 2004).

- Clinicians should be aware of predisposing risk factors for haemorrhage, and those considered ‘high risk’ should be encouraged to deliver in a consultant unit (CEMACH, 2004). However, PPH is unpredictable and can occur in women with no identifiable risk factors (AAFP, 2004).

- Insidious blood loss can occur, causing maternal fatality if not recognised early (AAFP, 2004).

The 4Ts

Tone (uterine atony)

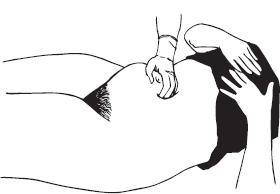

Around 70% of PPHs are caused by uterine atony. Predisposing risk factors include polyhydramnios, multiple pregnancy, high parity, prolonged/induced/augmented labours, instrumental delivery, pregnancy-induced hypertension, placental abruption, placenta praevia and PPH (AAFP, 2004). The aim of care is to deliver the placenta, if in situ, and ensure the uterus is well contracted by rubbing up a contraction and administering oxytocics (Fig. 15.1).

Fig. 15.1 Rubbing up a contraction.