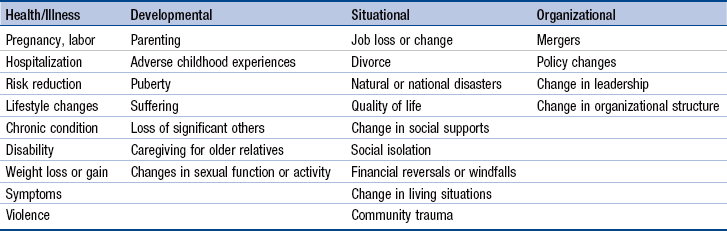

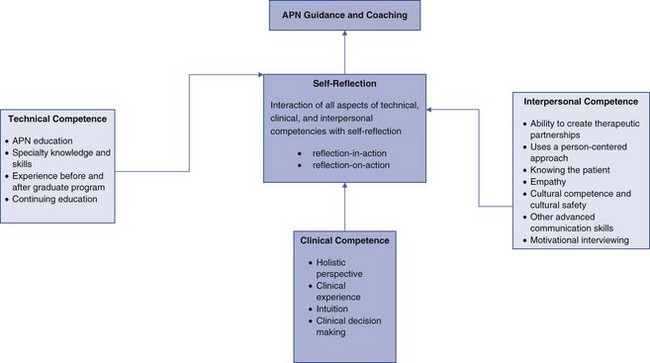

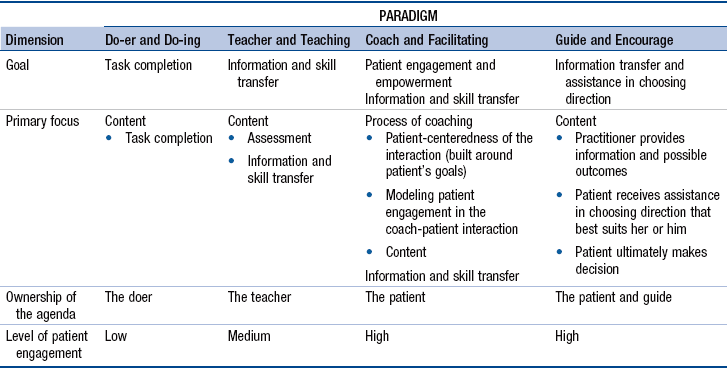

Chapter 8 Imperatives for Advanced Practice Nurse Guidance and Coaching Definitions: Teaching, Guidance, and Coaching Advanced Practice Nurse Guidance and Coaching Competency: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives Model of Advanced Practice Nurse Guidance and Coaching Clinical and Technical Competence Conflict Negotiation and Resolution Individual and Contextual Factors That Influence Advanced Practice Nurse Guidance and Coaching Development of Advanced Practice Nurses’ Coaching Competence Graduate Nursing Education: Influence of Faculty and Preceptors Strategies for Developing and Applying the Coaching Competency Professional Coaching and Health Care The competency of guidance and coaching is a well-established expectation of the advanced practice nurse (APN). For example, the ability to establish therapeutic relationships and guide patients through transitions is incorporated into the DNP Essentials (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006). Although there is variability in how this aspect of APN practice is described, standards that specifically address therapeutic relationships and partnerships, coaching, communication, patient-family–centered care, guidance, and/or counseling can be found in competency statements for most APN roles (American College of Nurse Midwives [ACNM, 2012]; National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists [NACNS], 2013; National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties [NONPF], 2012). • The foundational importance of the therapeutic APN-patient (client) relationship is not consistent with professional coaching principles. • The evolving criteria and requirements for certification of professional coaches are not premised on APN coaching skills. • Empirical research findings that predate contemporary professional coaching have affirmed that guidance and coaching are characteristics of APN-patient relationships. Nationally and internationally, chronic illnesses are leading causes of morbidity and mortality. In 2008, worldwide, over 36 million people died from conditions such as heart disease, cancers, and diabetes (World Health Organization [WHO], 2011, 2012). Similarly, in the United States, chronic diseases caused by heart disease result in 7 out of 10 deaths/year; cancer and stroke account for more than 50% of all deaths (Heron, Hoyert, Murphy, et al., 2009). In 2008, 107 million Americans had at least one of six chronic illnesses—cardiovascular disease, arthritis, diabetes, asthma, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HSS], 2012); this number is expected to grow to 157 million by 2020 (Bodenheimer, Chen, & Bennett, 2009). These diseases share four common risk factors that lend themselves to APN guidance and coaching—tobacco use, physical inactivity, the harmful use of alcohol, and poor diet. There is evidence that psychosocial problems, such as adverse childhood experiences, contribute to the initiation of risk factors for the development of poor health and chronic illnesses in Americans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010; Felitti, 2002). The physical, emotional, social, and economic burdens of chronic illness are enormous but, until recently, investing in resources to promote healthy lifestyles and prevent chronic illnesses has not been a policy priority. Registered nurses, including APNs, are central to a redesigned health system that emphasizes prevention and early intervention to promote healthy lifestyles, prevent chronic diseases, and reduce the personal, community, organizational, and economic burdens of chronic illness (Hess, Dossey, Southard, et al., 2012; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2010; Thorne, 2005). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA; HHS, 2011) in the United States and other policy initiatives nationally and internationally are aimed at lowering health costs and making health care more effective. The PPACA has led payers to adopt innovative approaches to financing health care, including accountable care organizations (ACOs) and patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs; see Chapter 22). To qualify as a medical or health care home or ACO, practices must engage patients and develop communication strategies. Thorne (2005) has analyzed findings from a decade of qualitative research on nurse-patient relationships and communication in chronic illness care in the context of the health policy emphasis on accountable care; many findings were associated with better outcomes. Accountable care initiatives are an opportunity to implement these findings and evaluate and strengthen the guidance and coaching competency of APNs. The aging population, increases in chronic illness, and the emphasis on preventing medical errors has led to calls for care that is more patient-centered (Devore & Champion, 2011; IOM, 2001; National Center for Quality Assurance [NCQA], 2011). The Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI] has asserted that patient-centered care is central to driving improvement in health care Johnson, Abraham, Conway, et al., 2008). The Joint Commission (TJC) published the Roadmap for Hospitals in 2010. Its purpose was “to inspire hospitals to integrate concepts from the communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care fields into their organizations” (TJC, 2010, p. 11). Similarly, two of ten criteria that primary care PCMHs are expected to meet are “written standards for patient access and communication” and “active support of patient self-management” (NCQA, 2011). In addition, patient-centered communication and interprofessional team communication are important quality and safety education for nurses (QSEN) competencies for APNs (Cronenwett, Sherwood, Pohl, et al., 2009; http://qsen.org/competencies/graduate-ksas/). These initiatives signal increasing recognition by all stakeholders that improving health care depends on a patient-centered orientation in which providers communicate meaningfully and effectively and provide culturally competent and safe care (IOM, 2010; Hobbs, 2009; TJC, 2010; Woods, 2010). The provision of patient-centered care and meaningful patient-provider communication activates and empowers patients and their families to assume responsibility for initiating and maintaining healthy lifestyles and/or adopting effective chronic illness management skills. When patient-centered approaches are integrated into the mission, values, and activities of organizations, better outcomes for patients and institutions, including safer care, fewer errors, improved patient satisfaction, and reduced costs, should ensue. APNs have the knowledge and skills to help institutions and practices meet the standards for meaningful provider-patient communication and team-based, patient-centered care. Over the last decade, the importance of interprofessional teamwork to achieve high-quality, patient-centered care has been increasingly recognized. The Interprofessional Collaborative Expert Panel (ICEP) has proposed four core competency domains that health professionals need to demonstrate if interprofessional collaborative practice is to be realized (ICEP, 2011; http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/ipecreport.pdf). These core competency domains are as follows: values and ethics for interprofessional practice; roles and responsibilities; interprofessional communication; and teams and teamwork. The competency related to teams and teamwork emphasizes relationship building as an important element of patient-centered care (see Chapter 12). As interprofessional teamwork becomes more integrated into health care, guidance and coaching will likely be seen as a transdisciplinary, patient-centered approach to helping patients but will be expressed differently, based on the discipline and experience of the provider. The publication of these competencies, together with research on interprofessional work in the health professions (e.g., Reeves, Zwarenstein, Goldman, et al., 2010), are helping educators determine how best to incorporate interprofessional competencies into APN education. Skill in establishing therapeutic relationships and being able to coach patients based on discipline-related content and skills will be important in achieving interprofessional, patient-centered care. APNs must be able to explain their nursing contributions, including their relational, communication, and coaching skills, to team members. Furthermore, many APNs will have responsibilities for coaching teams to deliver patient-centered care. Guidance and coaching by APNs have been conceptualized as a complex, dynamic, collaborative, and holistic interpersonal process mediated by the APN-patient relationship and the APN’s self-reflective skills (Clarke & Spross, 1996; Spross, Clarke, & Beauregard, 2000; Spross, 2009). To help the reader begin to discern the subtle differences among coaching actions, the terms that inform this model are defined here, in particular, patient education, APN guidance, including anticipatory guidance, and a revised definition of APN coaching (to distinguish it from professional coaching). Parry and Coleman (2010) have offered useful distinctions among different strategies for helping patients: coaching, doing for patients, educating, and guiding along five dimensions (Table 8-1). These distinctions are reflected in the definitions that follow. Distinctions Among Coaching and Other Processes Adapted from Parry, C. & Coleman, E. A. (2010). Active roles for older adults in navigating care transitions: Lessons learned from the care transitions intervention. Open Longevity Science, 4, 43–50. Patient teaching and education (see Chapter 7) directly relates to APN coaching. Teaching is an important intervention in the self-management of chronic illness and is often incorporated into guidance and coaching. “Patient education involves helping patients become better informed about their condition, medical procedures, and choices they have regarding treatment. Nurses typically have opportunities to educate patients during bedside conversations or by providing prepared pamphlets or handouts. Patient education is important to enable individuals to better care for themselves and make informed decisions regarding medical care” (Martin, eNotes, 2002, http://www.enotes.com/patient-education-reference/patient-education). This definition is necessarily broad and can inform standards for patient education materials and programs targeting common health and illness topics. Patient education may include information about cognitive and behavioral changes but these changes cannot occur by teaching alone. All nurses and APNs should be familiar with the patient education resources in their specialty because these resources can facilitate guidance and coaching. Guidance can be seen as a preliminary, less comprehensive form of coaching. A subtle distinction is that guidance is done by the nurse, whereas coaching’s focus is on empowering patients to manage their care needs. This definition of guidance draws on dictionary definitions of the word and the use of the term in motivational interviewing (MI). To guide is to advise or show the way to others, so guidance can be considered the act of providing counsel by leading, directing, or advising. To guide also means to assist a person to travel through, or reach a destination in, an unfamiliar area, such as by accompanying or giving directions to the person. The term is also used to refer to advising others, especially in matters of behavior or belief. Rollnick and colleagues (2008) have described guiding as one of three styles of doing MI. They compare a guiding style of communication to tutoring; the emphasis is on being a resource to support a person’s autonomy and self-directed learning and action. Anticipatory guidance is a particular type of guidance aimed at helping patients and families know what to expect. Such guidance needs to be wisely crafted to avoid “leading the witness” or creating self-fulfilling prophecies (see Exemplar 8-1). With experience, APNs develop their own strategies for integrating specialty-related anticipatory guidance into their coaching activities. APNs are likely to move between guidance and coaching in response to their assessments of patients. Although we believe that guidance is distinct from coaching, more work is needed to illuminate the differences and relationships between the two. The notion of transitions and the concept of transitional care have become central to policies aimed at reducing health care costs and increasing quality of care (Naylor, Aiken, Kurtzman, et al., 2011). Early work by Schumacher and Meleis (1994) remains relevant to the APN coaching competency and contemporary interventions, often delivered by APNs, designed to ensure smooth transitions for patients as they move across settings (e.g., Coleman & Boult, 2003; Coleman & Berenson, 2004; U.S. Aging and Disability Resource Center, 2011; Administration on Aging, 2012). Schumacher and Meleis (1994) have defined the term transition as a passage from one life phase, condition, or status to another: “Transition refers to both the process and outcome of complex person-environment interactions. It may involve more than one person and is embedded in the context and the situation” (Chick & Meleis, 1986, pp. 239-240). The definition speaks to the fact that others are affected by, or can influence, transitions. Transitions are paradigms for life and living. Becoming a parent, giving up cigarettes, learning how to cope with chronic illness, and dying in comfort and dignity are just a few examples of transitions. Similar to life, they may be predictable or unpredictable, joyous or painful, obvious or barely perceptible, chosen and welcomed, or unexpected and feared. Understanding patients’ perceptions of transition experiences is essential to effective coaching. Chick and Meleis (1986) have characterized the process of transition as having phases during which individuals experience the following: (1) disconnectedness from their usual social supports; (2) loss of familiar reference points; (3) old needs that remain unmet; (4) new needs; and (5) old expectations that are no longer congruent with the changing situation. Transitions can also be characterized according to type, conditions, and universal properties. Schumacher and Meleis (1994) have proposed four types of transitions—developmental, health and illness, situational, and organizational. Health and illness transitions were primarily viewed as illness-related and ranged from adapting to a chronic illness to returning home after a stay in the hospital (Schumacher and Meleis, 1994). In today’s health care system, transitions are not just about illness. They include adapting to the physiologic and psychological demands of pregnancy, reducing risk factors to prevent illness, changing unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, and numerous other clinical phenomena. Some health and illness changes are self-limiting (e.g., the physiologic changes of pregnancy), whereas others are long term and may be reversible or irreversible. In this chapter, health and illness transitions are defined as transitions driven by an individual’s experience of the body in a holistic sense. Studies have suggested that prior embodied experiences may play a role in the expression or the trajectory of a patient’s health/illness experience. For example, in the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010), adverse experiences in childhood, such as abuse and trauma, had strong relationships with health concerns, such as smoking and obesity. In a clinical case study, Felitti (2002) proposed that, although diabetes and hypertension were the “presenting concerns” in a 70-year-old woman, the first priority on her problem list should be the childhood sexual abuse she had experienced; effective treatment of the presenting illnesses would depend on acknowledging the abuse and referring the patient to appropriate therapy. Situational transitions are most likely to include changes in educational, work, and family roles. These can also result from changes in intangible or tangible structures or resources (e.g., loss of a relationship or financial reversals; Schumacher & Meleis, 1994). Developmental, health and illness, and situational transitions are the most likely to lead to clinical encounters requiring guidance and coaching. In practice, APNs remain aware of the possibility of multiple transitions occurring as a result of one salient transition. While eliciting information on the primary transition that led the patient to seek care, the APN attends to verbal, nonverbal, and intuitive cues to identify other transitions and meanings associated with the primary transition. Attending to the possibility of multiple transitions enables the APN to tailor coaching to the individual’s particular needs and concerns. Organizational transitions are those that occur in the environment; within agencies, between agencies, or in society. They reflect changes in structures and resources at a system level. Clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) typically have more involvement in planning and implementing organizational transitions. However, all APNs must be skilled in dealing with organizational transitions, because they tend to affect structural and contextual aspects of providing care. Table 8-2 lists some transitions, based on this typology, that might require APN coaching. Wise APNs pay attention to all four types of transitions in their personal and professional lives. Outcomes of successful transitions include subjective well-being, role mastery, and well-being of relationships (Schumacher and Meleis, 1994), all components of quality of life. This description of transitions as a focus for APN coaching underscores the need for and the importance of a holistic orientation to caring for patients. The transtheoretical model (TTM; also called the Stages of Change theory), is a model derived from several hundred psychotherapy and behavior change theories (Norcross, Krebs & Prochaska, 2011; Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, 2008). Based on studies of smokers, Prochaska and associates (2008) learned that behavior change unfolds through stages. TTM has been used successfully to increase medication adherence and to modify high-risk lifestyle behaviors, such as substance abuse, eating disorders, sedentary lifestyles, and unsafe sexual practices. Change is conceptualized as a five-stage process (Fig. 8-1), in which change can be hastened with skillful guidance and coaching. APNs can use the TTM model to tailor interactions and interventions to the patient’s specific stage of change to maximize the likelihood that they will progress through the stages of behavioral change. Earlier work on transitions by Meleis and others is consistent with and affirms the concepts of the TTM. For example, Chick and Meleis (1986) have characterized the process of transition as having phases during which individuals go through five phases (see earlier). These ideas are consistent with elements of the TTM and offer useful ideas for assessment. Making lifestyle or behavior changes are transitions; the stages of change are consistent with the characteristics of transition phases (Chick and Meleis, 1986). APNs can use nurses’ theoretical work on transitions to inform assessments and interventions during each of the TTM stages of change and tailor their guiding and coaching interventions to the stage of readiness. When clinicians adopt the language of change, it prevents labeling and prejudging patients, helps maintain positive regard for the patient, and creates a climate of safety and hope. Patients know that, if and when they are ready to change, the APN will collaborate with them. Quantitative studies, qualitative studies, and anecdotal reports have suggested that coaching patients and staff through transitions is embedded in the practices of nurses (Benner, Hooper-Kyriakidis, et al., 1999), and particularly APNs (Bowles, 2010; Cooke, Gemmill, & Grant, 2008; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hayes & Kalmakis, 2007; Hayes, McCahon, Panahi, et al., 2008; Link, 2009; Mathews, Secrest, & Muirhead, 2008; Parry & Coleman, 2010). APN-led patient education and monitoring programs for specific clinical populations have demonstrated that coaching is central to their effectiveness (Crowther, 2003; Brooten, Naylor, York, et al., 2002; Marineau, 2007). Teaching and counseling are significant clinical activities in nurse-midwifery (Holland & Holland, 2007) and CNS practice (Lewandoski & Adamle, 2009). Studies of NPs and NP students have indicated that they spend a significant proportion of their direct care time teaching and counseling (Lincoln, 2000; O’Connor, Hameister, & Kershaw, 2000). Early studies documented the nature, focus, content, and amount of time that APNs spent in teaching, guiding and coaching, and counseling, as well as the outcomes of these interventions (Brooten, Youngblut, Deatrick, et al., 2003; see Chapter 23). Furthermore, Hayes and colleagues (2008) have affirmed the importance of the therapeutic APN-patient alliance and have proposed that NPs who manage patients with chronic illness apply TTM in their practice, including the use of coaching strategies. Among the studies of APN care are those in which APNs provide care coordination for patients as they move from one setting to the other, such as hospital to home. Transitional care has been defined as “a set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of health care as patients transfer between different locations or different levels of care within the same location” (Coleman & Boult, 2003, p. 556). There are at least three types of evidence-based transitional care programs that have used APNs to support transitions from hospital to home (U.S. Agency on Aging and Disability Resource Center, 2011). Studies of the transitional care model (TCM) and care transitions intervention (CTI) have used APNs as the primary intervener. There is also a model of practice-based care coordination that used an NP and social worker, the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE) model (Counsell, Callahan, Buttar, et al., 2006). Based on transitional care research, the provision of transitional care is now regarded as essential to preventing error and costly readmissions to hospitals and is recognized and recommended in current U.S. health care policies (Naylor et al., 2011). Table 8-3 compares the three models of care transitions that used APNs. Because the GRACE model is similar to the TCM and CTI models, it will not be discussed further here. Care Transition Models Using Advanced Practice Nurses *Referred to as the Coleman model (Coleman et al., 2004) †Referred to as the Naylor model (Naylor et al., 2004). ‡Referred to as the GRACE model (Counsell et al., 2006). Adapted from the U.S. Aging and Disability Resource Center. (2011). Evidence-based care transitions models side-by-side March 2011 (adrc-tae.org/tiki-download_file.php?fileId=30310). Extensive research on the TCM has documented improved patient and institutional outcomes and led to better understanding of the nature of APN interventions. Currently, the TCM is a set of activities aimed at providing “comprehensive in-hospital planning and home follow-up for chronically ill high risk older adults hospitalized for common medical and surgical conditions” (Transitional Care Model, 2008-2009; http://www.transitionalcare.info/). Early studies of the model from which TCM evolved have provided substantive evidence of the range and focus of teaching and counseling activities undertaken initially by CNSs, and later NPs, who provided care to varied patient populations. Controlled trials of this model have found that APN coaching, counseling, and other activities demonstrate statistically significant differences in patient outcomes and resource utilization (e.g., Brooten, Roncoli, Finkler, et al., 1994; Naylor, Brooten, Campbell, et al., 1999). Secondary analyses of data from early transitional care trials have identified the specific interventions that APNs used for five different clinical populations (Naylor, Bowles, & Brooten, 2000): health teaching, guidance, and/or counseling; treatments and procedures; case management; and surveillance (Brooten et al., 2003). The most frequent intervention was surveillance; health teaching was the second or third most frequent intervention, depending on the patient population. APNs used a holistic focus that required clinical expertise, including sufficient patient contact, interpersonal competence, and systems leadership skills to improve outcomes (Brooten, Youngblut, Deatrick, et al., 2003). Currently, the TCM process is focused on older adults and consists of screening, engaging the older adult and caregiver, managing symptoms, educating and promoting self-management, collaborating, ensuring continuity, coordinating care, and maintaining the relationship (http://www.transitionalcare.info/). During an illness, patients may transition through multiple sites of care that place them at higher risk for errors and adverse events, contributing to higher costs of care. Building on findings from studies of the TCM, the CTI program supports older adults with complex medical needs as they move throughout the health care system (Parry and Coleman, 2010). Coleman and colleagues have found results similar to those of TCM, a decreased likelihood of being readmitted and an increased likelihood of achieving self-identified personal goals around symptom management and functional recovery (Coleman, Smith, Frank, et al. 2004). Findings were sustained for as long as 6 months after the program ended. Subsequent studies of CTI have demonstrated significant reductions in 30-, 90-, and 180-day hospital readmissions (Coleman, Parry, Chalmers & Min, 2006). Because motivational interviewing (MI) has been part of CTI training, these findings suggest that integration of TTM key principles into APN practice, such as helping patients identify their own goals and having support (coaching) in achieving them, contributes to successful coaching outcomes. Based on their observations of creating and implementing the CTI with coaches of different backgrounds, Parry and Coleman (2010) have asserted that coaching differs from other health care processes, such as teaching and coordination. Instead of providing the patient with the answers, the coach supports the patient and provides the tools needed to manage the illness and navigate the health care system. According to these authors, a commitment and ability to adopt a coaching role and foster empowerment and confidence in the patient is more important than a disciplinary background. As APN-based transitional care programs evolve, researchers are examining whether other, sometimes less expensive providers can offer similar services and achieve the same outcome. For example, TCM programs have begun to use baccalaureate-prepared nurses to provide transitional care; Parry and Coleman (2010) have reported on the use of other providers in CTI interventions, including social workers. These initiatives suggest that APNs, administrators, and researchers need to identify those clinical populations for whom APN coaching is necessary. In medically complex patients, APNs may be preferred and less expensive coaches, in part because of their competencies and scopes of practice. Several assumptions underlie this model: 1. APNs involve the patient’s significant other or patient’s proxy, as appropriate. 2. Although technical competence and clinical competence may be sufficient for teaching a task, they are insufficient for coaching patients through transitions, including chronic illness experiences or behavioral and lifestyle changes. For example, patients with diabetes may be taught how to monitor their blood sugar levels and administer insulin with technical accuracy, but if the lifestyle impacts of the transition from health to chronic illness are not evaluated, guidance and coaching do not occur. 3. Although guidance and coaching skills are an integral part of professional nursing practice, the clinical and didactic content of graduate education extends the APN’s repertoire of skills and abilities, enabling the APN to coach in situations that are broader in scope or more complex in nature. 4. APNs also apply their guidance and coaching skills in interactions with colleagues, interprofessional team members, students, and others. 5. Effective guidance and coaching of patients, family members, staff, and colleagues depend on the quality of the therapeutic or collegial relationships that APNs establish with them. 6. As with other APN core competencies, the coaching competency develops over time, during and after graduate education. The APN guidance and coaching competency reflects an integration of the characteristics of the direct clinical practice competency (see Chapter 7) but is particularly dependent on the formation of therapeutic partnerships with patients, use of a holistic perspective and reflective practice, and interpersonal interventions. Individual elements of the model include clinical, technical, and interpersonal competence mediated by self-reflection. In identifying these elements, the model of APN guidance and coaching breaks down what is really a holistic, flexible, and often indescribable process. As APNs assess, diagnose, and treat a patient, they are attending closely to the meanings that patients ascribe to health and illness experiences; APNs take these meanings into account in working with patients. APNs also attend to patterns, consciously and subconsciously, that develop intuition and contribute to their clinical acumen. The aim in offering this model is not only to help APNs understand what coaching is but to give them language by which to explain their interpersonal effectiveness. It is important to note that all elements of the model work synergistically to create this competency; separating them for the sake of discussion is somewhat artificial. APNs integrate self-reflection and the competencies they have acquired through experience and graduate education with their assessment of the patient’s situation—that is, patients’ understandings, vulnerabilities, motivations, goals, and experiences. Guidance and coaching require that APNs be self-aware and self-reflective as an interpersonal transaction is unfolding so that they can shape communications and behaviors to maximize the therapeutic goals of the clinical encounter. Thus, guidance and coaching by APNs represent an interaction of four factors: the APN’s interpersonal, clinical, and technical competence and the APN’s self-reflection (Fig. 8-2). These factors are further influenced by individual and contextual factors. The interaction of self-reflection with these three areas of competence, and clinical experiences with patients, drive the ongoing expansion and refinement of guiding and coaching expertise in advanced practice nursing. Self-reflection is the deliberate internal examination of experience so as to learn from it. The APN uses self-reflection during and after interactions with patients, classically described as reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action (Schön, 1983, 1987). Reflection in action is the ability to pay attention to phenomena as they are occurring, giving free rein to one’s intuitive understanding of the situation as it is unfolding; individuals respond with a varied repertoire of exploratory and transforming actions best characterized as strategic improvisation. APN coaching is analogous to the flexible and inventive playing of a jazz musician. Reflection-in-action requires astute awareness of context and investing in the present moment with full concentration, capabilities that take time to master and require regular practice.

Guidance and Coaching

Imperatives for Advanced Practice Nurse Guidance and Coaching

Burden of Chronic Illness

Health Care Policy Initiatives

Accountable Care Organizations and Patient-Centered Medical Homes

Patient-Centered Care, Culturally Competent and Safe Health Care, and Meaningful Provider-Patient Communication

Interprofessional Teams

Definitions: Teaching, Guidance, and Coaching

![]() TABLE 8-1

TABLE 8-1

Patient Education

Guidance

Advanced Practice Nurse Guidance and Coaching Competency: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives

Transitions in Health and Illness

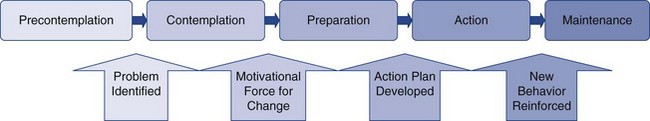

Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change

Stages of Change

Maintenance

Evidence That Advanced Practice Nurses Guide and Coach

Advanced Practice Nurses and Models of Transitional Care

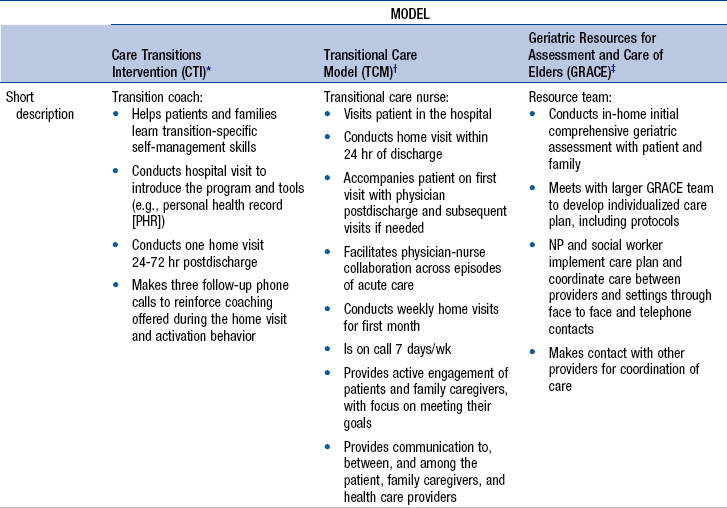

![]() TABLE 8-3

TABLE 8-3

Transitional Care Model

Care Transitions Intervention Model

Model of Advanced Practice Nurse Guidance and Coaching

Assumptions

Overview of the Model

Self-Reflection

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access