Giving Birth

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe maternal and fetal responses to labor.

• Explain how components of the birth process affect the course of labor.

• Relate mechanisms of labor to the process of vaginal birth.

• Explain premonitory signs of labor.

• Compare true labor with false labor.

• Describe common differences in the labors of nulliparous and parous women.

• Compare the stages of labor and the phases within the first stage.

• Describe admission and continuing intrapartum nursing assessments.

• Identify nursing priorities when assisting the woman to give birth under emergency circumstances.

• Relate therapeutic communication skills to care of the intrapartum family.

• Apply the nursing process to care of the woman experiencing false labor.

• Apply the nursing process to care of the woman and her family during the intrapartum period.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

Care of the woman and her family during labor and birth is a rewarding field of nursing. The birth of a baby is more than a physical event; it has deep personal and social significance for the family. Family roles and relationships are forever altered by this event.

Issues for New Nurses

Common issues face new nurses and nursing students when caring for families during birth.

Pain Associated with Birth

Working with people in pain is difficult, and most nurses feel compelled to relieve pain promptly. Yet pain is an expected part of labor and cannot be eliminated. Helping the woman manage the pain of birth is a crucial part of nursing care.

Inexperience or Negative Experiences

The nurse who has never given birth may feel inadequate to care for laboring women, although she or he rarely feels it necessary to have a fracture to care for someone with that problem. Nursing skills needed by the intrapartum nurse are basic: observation, critical thinking, problem solving, therapeutic communication, comfort promotion, empathy, and common sense.

Nurses also may be anxious because of their own difficult experiences during pregnancy or birth. They must be careful not to convey negative attitudes to the laboring woman and her partner.

Unpredictability

Labor is a natural process that follows its own timetable. Some occurrences simply are not easily predicted or explained. Some nurses find the uncertain nature of intrapartum care troubling, whereas others find it exciting. Some days are busy from the start, whereas others are uncannily quiet, only to erupt in adrenaline-charged action with no warning.

Intimacy

The intimate nature of intrapartum care and its sexual overtones also make some nurses uncomfortable. They may feel that they are intruding on a private time.

The male nurse often finds this aspect of intrapartum care most anxiety provoking. Although he may have cared for other female clients, his care has not been this focused on the reproductive system. He often wonders how a woman’s male partner will accept him as a care provider.

The best approach for both male and female nurses is to maintain professional conduct and take cues from the couple. If they want privacy, the nurse should intervene only as needed to assess the woman and fetus. In more advanced labor, both partners often welcome the presence of a competent, caring nurse of either sex.

Physiologic Effects of the Birth Process

Labor and birth affect the physiologic systems of both the pregnant woman and her fetus. These effects are most striking in the maternal reproductive system and in relation to fetal and neonatal oxygenation.

Maternal Response

Significant changes during labor occur in the woman’s cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, urinary, and hematopoietic systems as well as in her reproductive system.

Reproductive System

Characteristics of Contractions

Normal labor contractions are coordinated, involuntary, and intermittent.

Coordinated Contractions

The uterus can contract and relax in a coordinated way, as can other smooth muscles such as the heart. As the woman approaches full term, contractions become organized and gradually assume a regular pattern of increasing frequency, duration, and intensity during labor. Coordinated labor contractions begin in the uterine fundus and spread downward toward the cervix to propel the fetus through the pelvis.

Involuntary Contractions

Uterine contractions are not under conscious control, as are skeletal muscles. The mother cannot cause labor to start or stop by conscious effort. Walking or other activity may stimulate existing labor contractions. Anxiety and excessive stress can diminish them.

Intermittent Contractions

Labor contractions are intermittent rather than sustained, allowing relaxation of the uterine muscle and resumption of blood flow to and from the placenta to permit gas, nutrient, and waste exchange for the fetus.

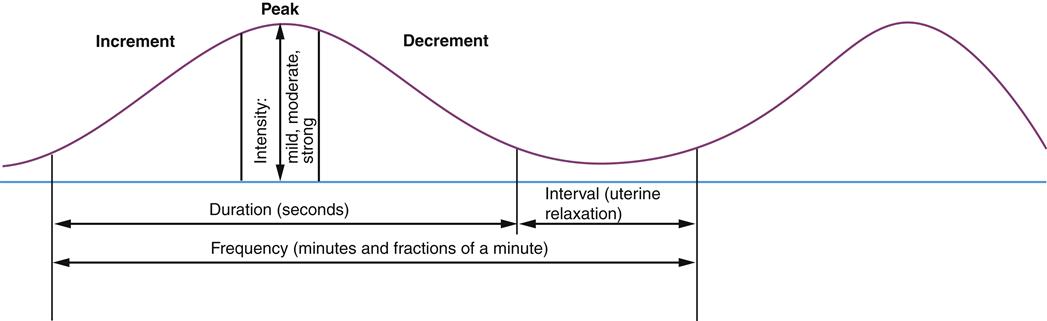

Contraction Cycle

Each contraction consists of three phases (Figure 16-1). The increment occurs as the contraction begins in the fundus and spreads throughout the uterus. The peak, or acme, is the period during which the contraction is most intense. The decrement is the period of decreasing intensity as the uterus relaxes.

The contraction cycle and the overall pattern of contractions are also described in terms of frequency, duration, and intensity. Frequency is the period from the beginning of one uterine contraction to the beginning of the next; it is usually expressed in minutes and fractions of minutes. For example, the nurse states, “Contractions are 3½ to 4 minutes apart.”

Duration is the length of each contraction from beginning to end; it is usually expressed in seconds. For example, the nurse might report, “Her contractions last 55 to 65 seconds.”

Intensity is the strength of the contractions. The terms “mild,” “moderate,” and “strong” are used to describe contraction intensity as palpated by the nurse. Mild contractions are often described as feeling like the tip of the nose, moderate contractions like the chin, and firm contractions like the forehead. Different descriptions of intensity may apply when the electronic fetal monitor is used to record contractions (see Chapter 17).

The interval is the period between the end of one contraction and the beginning of the next. The interval is the time when most fetal exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products occurs.

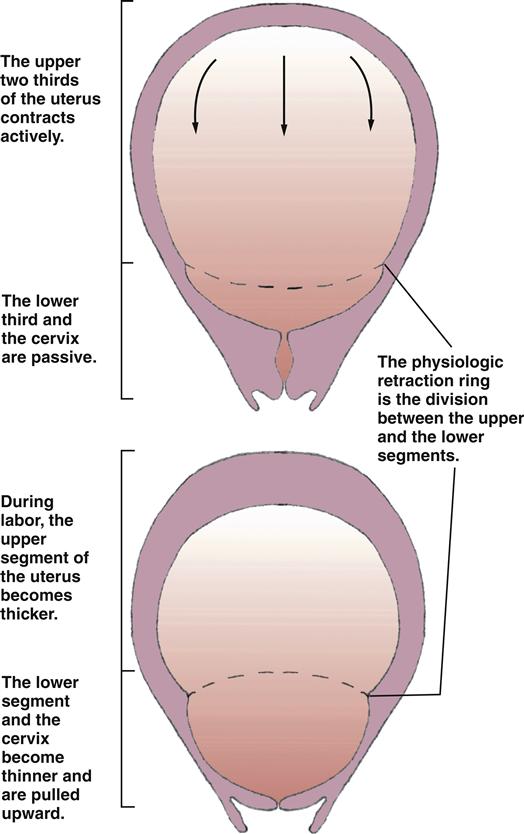

Uterine Body

Uterine activity during labor is characterized by opposing features. The upper two thirds of the uterus contracts actively to push the fetus down. The lower one third of the uterus remains less active, allowing downward passage of the fetus. The cervix is similar to the lower uterine segment in that it is also passive. The net effect of labor contractions is enhanced because the downward push from the upper uterus is accompanied by reduced resistance to fetal descent in the lower uterus.

Myometrial (uterine muscle) cells in the upper uterus remain shorter at the end of each contraction rather than returning to their original length. In contrast, myometrial cells in the lower uterus become longer with each contraction. These two characteristics enable the upper uterus to maintain tension between contractions to preserve the cervical changes and downward fetal progress made with each contraction.

The opposing characteristics of myometrial contraction in the upper and lower uterine segments cause changes in the thickness of the uterine wall during labor. The upper uterus becomes thicker while the lower uterus becomes thinner and pulled upward during labor. The physiologic retraction ring marks the division between the upper and lower segments of the uterus (Figure 16-2).

The opposing characteristics of contractions in the upper and lower uterine segments change the shape of the uterine cavity, which becomes more elongated and narrower as labor progresses. This change in uterine shape straightens the fetal body and efficiently directs it downward in the pelvis.

Cervical Changes

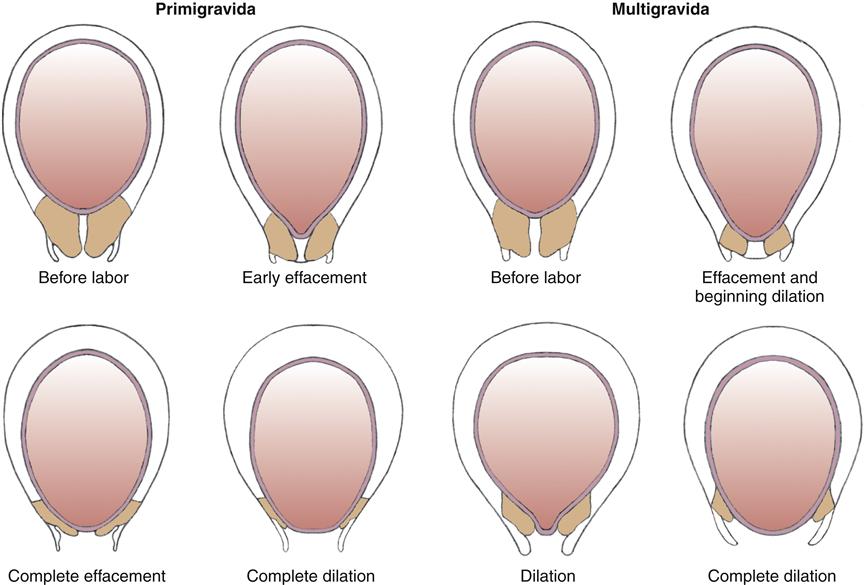

Effacement (thinning and shortening) and dilation (opening) are the major cervical changes during labor. Effacement and dilation occur together during labor but at different rates. The nullipara completes most cervical effacement early in the process of cervical dilation. In contrast, the parous woman’s cervix is usually thicker than a nullipara’s cervix at any point during labor.

Effacement

Before labor the cervix is a cylindric structure, about 2 cm long, at the lower end of the uterus. Labor contractions push the fetus downward against the cervix as they pull the cervix upward. The cervix becomes shorter and thinner as it is drawn over the fetus and amniotic sac (Figure 16-3). The cervix merges with the thinning lower uterus rather than remaining a distinct cylindric structure. Effacement is estimated as a percentage of the amount the cervix has thinned, so that a fully thinned cervix is 100% effaced. Effacement also may be recorded as cervical length, estimated in centimeters during vaginal examination.

Dilation

As the cervix is pulled upward and the fetus is pushed downward, the cervix dilates. Dilation is expressed in centimeters, with approximately 10 cm being full dilation, large enough to allow passage of the average-size term fetus. The action during effacement and dilation can be likened to pushing a tennis ball out the cuff of a sock.

Cardiovascular System

During each uterine contraction, blood flow to the placenta gradually decreases, causing a relative increase in the woman’s blood volume. This temporary change increases her blood pressure slightly and slows her pulse. Therefore the mother’s vital signs are best assessed during the interval between contractions.

Although it is more likely to occur during the antepartum period because the fetus has not yet started to descend, supine hypotension also may occur during labor if the mother lies on her back (see Figure 13-4). The mother should be encouraged to rest in positions other than the supine to promote blood return to her heart and therefore enhance blood flow to the placenta and promote fetal oxygenation.

Respiratory System

The depth and rate of respirations increase, especially if the woman is anxious or in pain. A woman who breathes rapidly and deeply may experience symptoms of hyperventilation if she exhales too much carbon dioxide. She may feel tingling in her hands and feet, numbness, and dizziness. Helping her to slow her breathing and to breathe into a paper bag or her cupped hands can restore normal blood levels of carbon dioxide and relieve these symptoms.

Gastrointestinal System

Gastric motility is reduced to varying degrees during labor. Most women are not hungry but are often thirsty and have a dry mouth. Food and large volumes of liquids are usually limited to reduce the risk of vomiting and aspiration if unexpected surgery is needed. Ice chips are commonly provided, as are small amounts of other clear liquids or juices, Popsicles, or hard candy. Large amounts of sugar are not desirable because they may cause rebound hypoglycemia in the newborn when the sugar supply abruptly ends at birth.

Urinary System

The most common change in the urinary system during labor is reduced sensation of a full bladder. Because of intense contractions or the effects of regional pain management such as epidural, the woman may be unaware that her bladder is full. Yet a full bladder may contribute to general discomfort that remains after regional analgesia. A full bladder can also inhibit fetal descent because it occupies space in the pelvis.

After birth, the fluid retention that is normal during pregnancy is quickly reversed, and urine is excreted in large quantities. The bladder may fill rapidly during the first few days after birth.

Hematopoietic System

Many authorities recognize 500 mL as a normal average blood loss during vaginal birth although women may often lose and tolerate greater loss well because the blood volume increases during pregnancy by 1 to 2 L. Quantitative rather than estimated blood loss is often higher than the estimate. A hemoglobin of 11 g/dL and a hematocrit of 33% or higher give most women an adequate margin of safety for blood loss associated with normal birth. The leukocyte count averages 14,000 to 16,000/mm3 but may be as high as 25,000/ mm3 or higher during labor, a level that might otherwise suggest infection (Blackburn, 2013; Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010; Hall, 2011).

Levels of several clotting factors, especially fibrinogen, are elevated during pregnancy and continue to be higher during labor and after delivery. Fibrinolysis (clot breakdown) decreases during labor to promote coagulation at the placental site. Although the increase in clotting factors and decrease in fibrinolysis protect from hemorrhage, the combination also raises the mother’s risk for venous thrombosis during pregnancy and after birth.

Fetal Response

Fetal responses are most notable in the placental circulation, the cardiovascular system, and the pulmonary system.

Placental Circulation

Exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products between mother and fetus occurs in the intervillous spaces (see Chapter 12). During strong labor contractions, the maternal blood supply to the placenta stops intermittently as the spiral arteries supplying the intervillous spaces are compressed by the uterine muscle. Therefore most placental exchange occurs during the interval between contractions.

The placental circulation usually has enough reserve over fetal basal needs to tolerate the intermittent interruption of blood flow. The fetus has protective mechanisms, such as fetal hemoglobin (which more readily takes on oxygen and releases carbon dioxide), a high hematocrit, and a high cardiac output. The fetus may not tolerate labor contractions well in conditions associated with reduced placental function, such as maternal diabetes or hypertension, or in conditions associated with reduced fetal oxygen–carrying capacity, such as fetal anemia.

Cardiovascular System

The fetal cardiovascular system reacts quickly to events during labor. The fetal heart rate (FHR) is rapid, ranging from 110 to 160 beats per minute (bpm) at term (Lyndon, O’Brien-Abel, & Simpson, 2009). The preterm fetus may have a slightly higher heart rate than the term fetus, although persistent high FHRs at any gestation should be investigated (see Chapter 17 for more discussion of FHR and responses during labor).

Pulmonary System

Before birth, the fetal lungs are filled with fluid to allow normal development of the airways. This fluid must be cleared to allow air breathing. As term approaches, production of fetal lung fluid decreases and its absorption increases. Labor intensifies the absorption of lung fluid. Some fluid is expelled from the upper airways as the fetal head and thorax are compressed during passage through the birth canal. The remaining fluid is absorbed into the newborn’s pulmonary and lymphatic circulations after birth. Chapter 21 contains added information about newborn transition.

Components of the Birth Process

Four major factors, often called the “four Ps,” interact during normal childbirth. They are the powers, the passage, the passenger, and the psyche.

Powers

The two powers of labor are uterine contractions and maternal pushing efforts.

Uterine Contractions

During the first stage of labor (onset through full cervical dilation), uterine contractions are the primary force moving the fetus through the maternal pelvis.

Maternal Pushing Efforts

At some point during the second stage of labor (full cervical dilation through birth of the baby), the woman adds her voluntary pushing efforts to the force of uterine contractions to propel the fetus through the pelvis.

Passage

The passage for birth of the fetus consists of the maternal pelvis and its soft tissues. The bony pelvis is usually more important to the outcome of labor than the soft tissue because the bones and joints do not readily yield to the forces of labor. However, softening of the cartilage linking the pelvic bones increases as term approaches and the hormone relaxin increases.

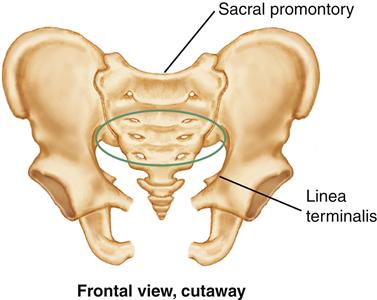

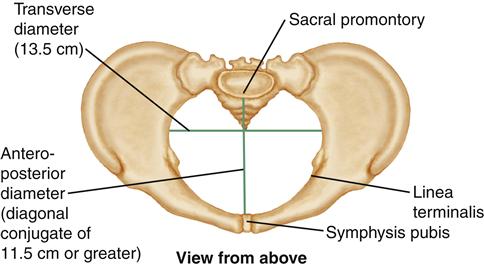

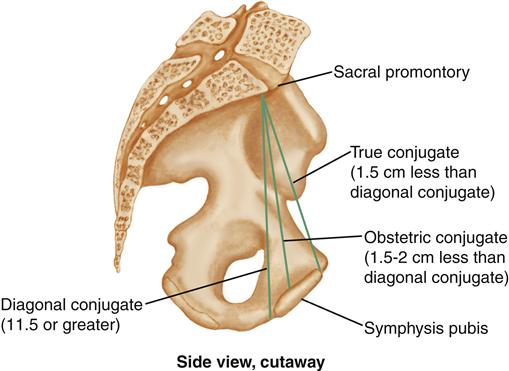

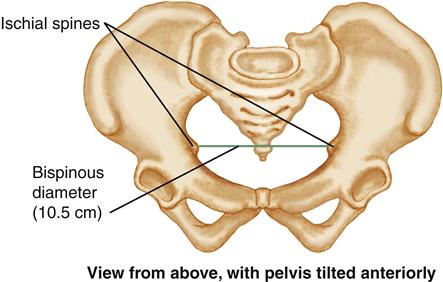

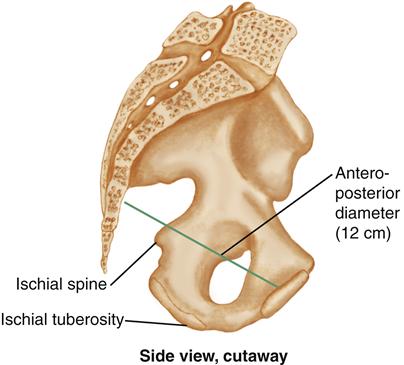

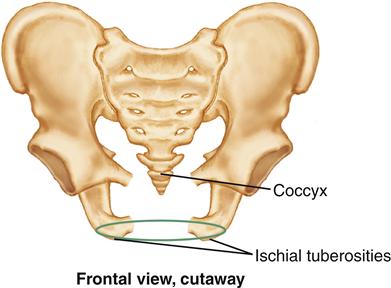

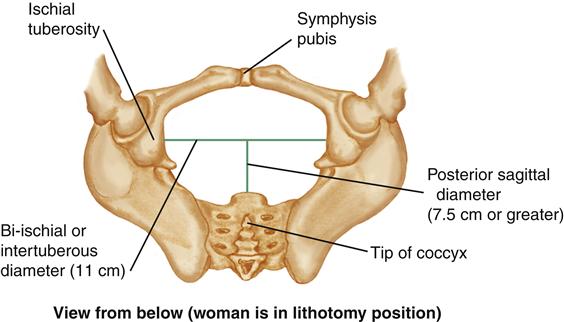

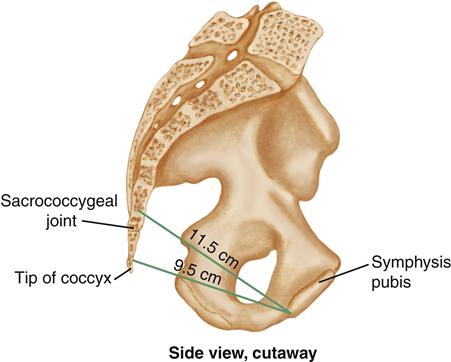

The bony pelvis is divided by the linea terminalis (or pelvic brim) into the false pelvis above and the true pelvis below (see Chapter 11). The true pelvis is most important in childbirth. The true pelvis has three subdivisions: (1) the inlet, or upper pelvic opening; (2) the midpelvis, or pelvic cavity; and (3) the outlet, or lower pelvic opening. The true pelvis is like a curved cylinder with different dimensions at different levels. Figure 16-4 (pp. 322-323) illustrates important pelvic measurements.

INLET

The boundaries of the inlet are the symphysis pubis anteriorly, the sacral promontory posteriorly, and the linea terminalis on the sides. The inlet is slightly wider in its transverse diameter (13.5 cm) than in its anteroposterior (diagonal conjugate) diameter (11.5 cm or greater).

The diagonal conjugate is slightly larger than both the obstetric and true conjugates. The obstetric conjugate is the narrowest of the three conjugate diameters but cannot be measured directly. The obstetric conjugate is estimated by first measuring the diagonal conjugate and then subtracting 1.5 to 2 cm.

If the inlet is small, the fetal head may not be able to enter it. Because it is almost entirely surrounded by bone, except for cartilage at the sacroiliac joint and symphysis pubis, the inlet cannot enlarge much to accommodate the fetus. The bony measurements are essentially fixed. MIDPELVIS

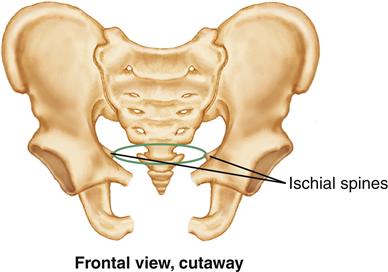

The midpelvis, or pelvic cavity, is the narrowest part of the pelvis through which the fetus must pass during birth. Midpelvic diameters are measured at the level of the ischial spines. The anteroposterior diameter averages 12 cm.

The transverse diameter (bispinous or interspinous) averages 10.5 cm. Prominent ischial spines that project into the midpelvis can reduce the bispinous diameter. OUTLET

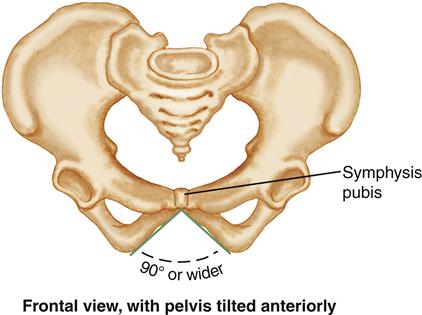

Three important diameters of the pelvic outlet are (1) the anteroposterior, (2) the transverse (bi-ischial or intertuberous), and (3) the posterior sagittal. The angle of the pubic arch also is an important pelvic outlet measure.

The anteroposterior diameter ranges from 9.5 to 11.5 cm, varying with the curve between the sacrococcygeal joint and the tip of the coccyx. The anteroposterior diameter can increase if the coccyx is easily movable.

The transverse diameter is the bi-ischial, or intertuberous, diameter. This is the distance between the ischial tuberosities (“sit bones”). It averages 11 cm.

The posterior sagittal diameter is normally at least 7.5 cm. It is a measure of the posterior pelvis. The posterior sagittal diameter measures the distance from the sacrococcygeal joint to the middle of the transverse (bi-ischial) diameter. The angle of the pubic arch is important because it must be wide enough for the fetus to pass under it. The angle of the pubic arch should be at least 90 degrees. A narrow pubic arch displaces the fetus posteriorly toward the coccyx as it tries to pass under the arch.

Passenger

The passenger is the fetus plus the membranes and placenta.

Fetal Head

The fetus enters the birth canal in the cephalic presentation more than 96% of the time. The fetal shoulders are important because of their width, but they usually flex and adapt to the pelvis.

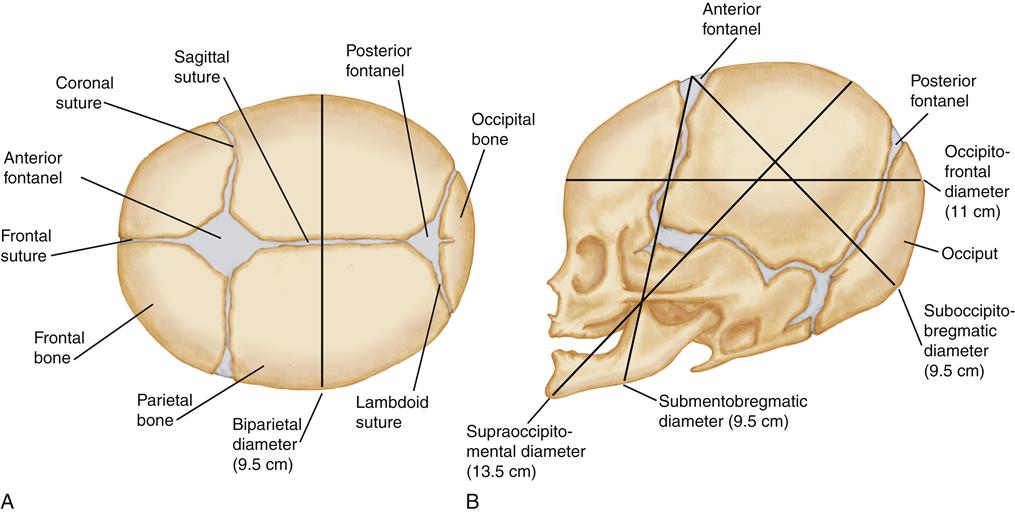

Bones, Sutures, and Fontanels

The bones of the fetal head involved in birth are the two frontal bones on the forehead, the two parietal bones at the crown of the head, and the occipital bone at the back of the head (Figure 16-5, p. 324). The five major bones are not fused but are connected by sutures composed of strong but flexible fibrous tissue. The fontanels are wider spaces at the intersections of the sutures.

The anterior fontanel is diamond shaped and formed by the intersection of four sutures: the two coronal, the frontal, and the sagittal, which connect the two frontal and the two parietal bones. The posterior fontanel has a triangular shape formed by the intersection of three sutures, one sagittal and two lambdoid, which connect the two parietal bones and the occipital bone. The posterior fontanel is very small, often more like a slight depression in the skull. The sutures and fontanels allow the bones to move slightly, changing the shape of the fetal head so that it can adapt to the size and shape of the pelvis by molding. The sutures and the different shapes of the fontanels provide landmarks to determine fetal position and head flexion during vaginal examination.

Fetal Head Diameters

Although most fetuses enter the pelvis in the cephalic presentation, several variations are possible. The major transverse diameter of the fetal head is the biparietal, measured between the two parietal bones and averages 9.5 cm in a term fetus.

The anteroposterior diameter of the head varies with the degree of flexion. In the most favorable situation, the head becomes fully flexed during labor and the anteroposterior diameter is the suboccipitobregmatic, averaging 9.5 cm. See Figure 16-5, B, on p. 324, for anteroposterior head diameters in different degrees of head flexion and extension.

Variations in the Passenger

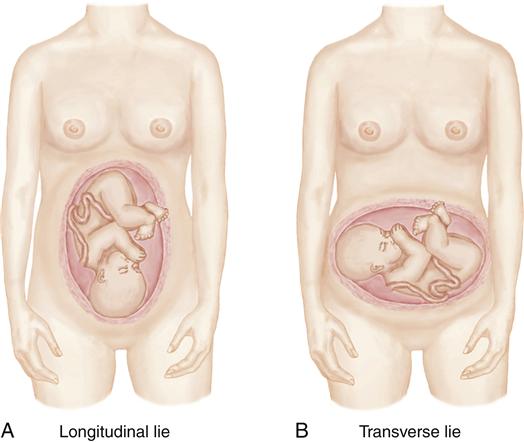

Fetal Lie

The orientation of the long axis of the fetus to the long axis of the woman is the fetal lie (Figure 16-6, p. 324). In more than 99% of pregnancies, the lie is longitudinal, or parallel to the long axis of the woman. In the longitudinal lie, either the head or buttocks of the fetus enter the pelvis first. A transverse lie exists when the long axis of the fetus is at right angles to the woman’s long axis; it occurs in less than 1% of pregnancies. An oblique lie is one at some angle between the longitudinal lie and the transverse lie.

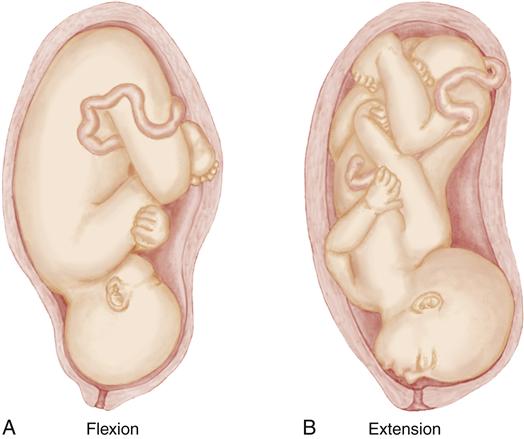

Attitude

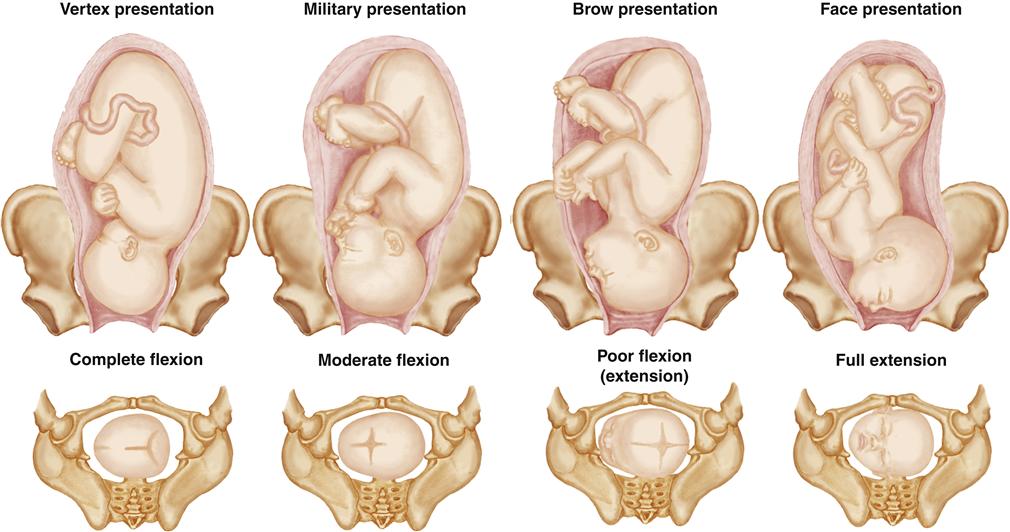

The attitude of the fetus is the relation of fetal body parts to each other (Figure 16-7, p. 324). The normal fetal attitude is one of flexion, with the head flexed toward the chest and the arms and legs flexed over the thorax. The back is curved in a convex C shape as labor starts.

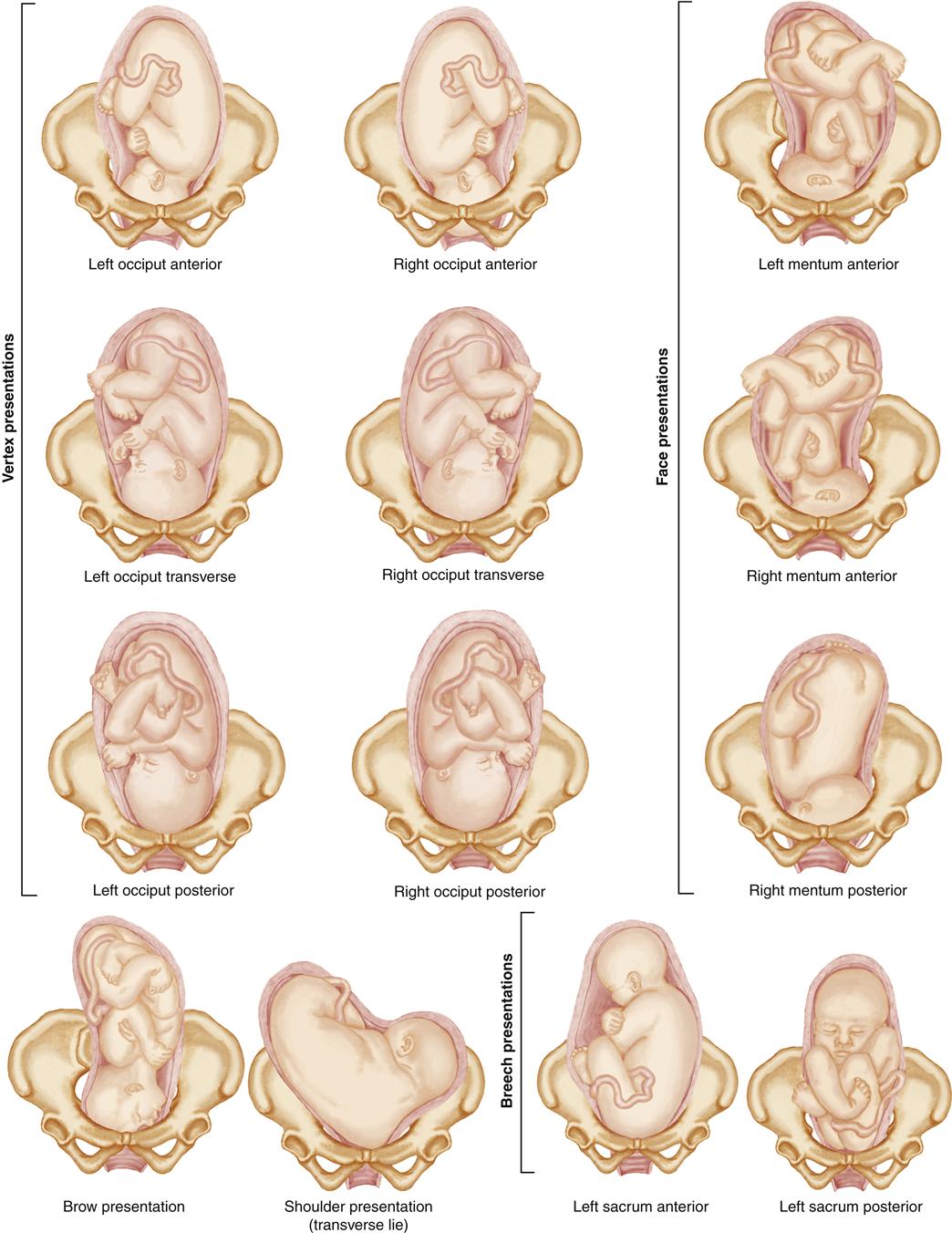

Presentation

The fetal part that enters the pelvis first is the presenting part. Presentation falls into three categories: (1) cephalic, (2) breech, and (3) shoulder. The cephalic presentation with the fetal head flexed is the most common (Figure 16-8, p. 325). Other presentations are associated with prolonged labor or other problems and are more likely to require cesarean birth.

Cephalic Presentation

The cephalic presentation is more favorable than others, for several reasons:

Cephalic presentation has four variations (see Figure 16-8).

Vertex

The vertex presentation is the most common cephalic presentation. The fetal head is fully flexed. This presentation is the most favorable for normal progress of labor because the smallest suboccipitobregmatic diameter is presenting.

Military

In a military, or sinciput, presentation the head is in a neutral position, neither flexed nor extended. The occipitofrontal diameter is presenting. This presentation is usually temporary and the head flexes into the vertex position or extends into the brow position.

Brow

In a brow presentation the fetal head is partly extended. The longest supraoccipitomental diameter is presenting.

Face

In a face presentation, the head is fully extended and the fetal occiput is near the fetal spine. The submentobregmatic diameter is presenting.

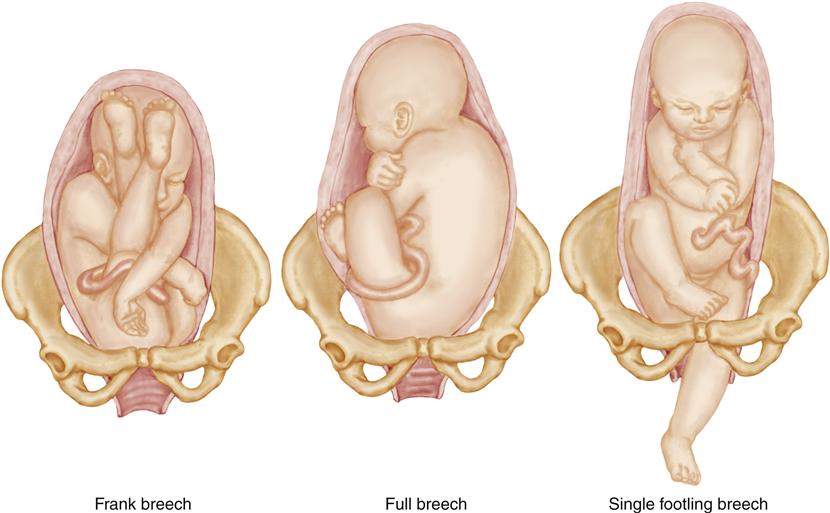

Breech Presentation

A breech presentation occurs when the fetal buttocks or feet enter the pelvis first. They are common, occurring in approximately about 3% of births (Cunningham et al., 2010; Tarsa & Moore, 2010). Breech presentations are associated with several disadvantages:

The breech presentation has three variations, depending on the relationship of the legs to the body (Figure 16-9).

Frank breech

In the most common frank breech presentation the fetal legs are extended across the abdomen toward the shoulders.

Full (or complete) breech

The full breech is a reversal of the usual cephalic presentation. The head is flexed, and the knees and hips are also flexed, but the buttocks are presenting.

Footling breech

The footling breech occurs when one or both feet are presenting.

Shoulder

The shoulder presentation is a transverse lie and accounts for fewer than 1% of births, usually premature (Cunningham et al., 2010; Tarsa & Moore, 2010). A cesarean birth is necessary.

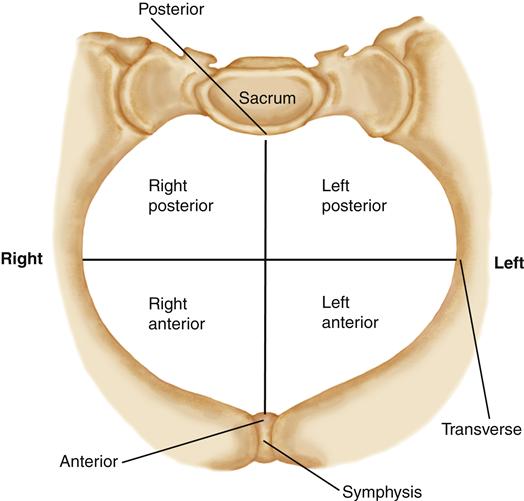

Position

Fetal position describes the location of a fixed reference point on the presenting part in relation to the four quadrants of the maternal pelvis (Figure 16-10): right and left anterior and right and left posterior. The fetal position is not fixed but rather changes during labor as the fetus moves downward and adapts to the pelvic contours. Abbreviations indicate the relationship between the fetal presenting part and the maternal pelvis.

Right (R) or Left (L)

The first letter of the abbreviation describes whether the fetal reference point is in the right or the left of the mother’s pelvis. If the fetal point is neither to the right nor to the left of the pelvis, this letter is omitted.

Occiput (O), Mentum (M), or Sacrum (S)

The second letter of the abbreviation refers to the fixed fetal reference point, which varies with the presentation. The occiput is used in a vertex presentation. The chin, or mentum, is the reference point in a face presentation. The sacrum is used for breech presentations. Letters may also designate the less common brow (F for fronto) and shoulder (Sc for scapula) presentations.

Anterior (A), Posterior (P), or Transverse (T)

The third letter describes whether the fetal reference point is in the anterior or the posterior quadrant of the mother’s pelvis. If the fetal reference point is in neither the anterior nor the posterior quadrant, it is described as transverse.

If the fetal occiput is located in the left anterior quadrant of the mother’s pelvis, the position is described as left occiput anterior (LOA). If the occiput is in the mother’s anterior pelvis, neither to the right nor to the left, it is described as occiput anterior (OA). If the fetal sacrum is located in the mother’s right posterior pelvis, the description is R (right) S (sacrum) P (posterior). See Figure 16-11 for different fetal presentations and positions.

Psyche

The psyche is a crucial part of childbirth. Marked anxiety, fear, or fatigue decreases a woman’s ability to cope with pain in labor. Maternal catecholamines secreted in response to anxiety or fear can inhibit uterine contractility and placental blood flow. Relaxation, however, augments the natural process of labor.

Interrelationships of the Components of Birth

The four Ps—the powers, passage, passenger, and psyche—are an interrelated whole. For example, a woman with a small pelvis (passage) and a large fetus (passenger) can have a normal labor and birth if the fetus is ideally positioned and the uterine contractions and maternal bearing-down efforts (powers) are vigorous. The nurse’s supportive attitude strengthens positive psychological elements (psyche) and enhances the processes of birth. The nurse can act as an advocate for the laboring woman and her family or partners to increase their sense of control and mastery of labor, often reducing anxiety and fear.

Individual and Cultural Values

A family’s culture affects its members’ views of birth and the practices that surround it. Culture shapes the values that people hold, their expectations of the birth experience, and their responses to birth. A woman’s culture gives her cues about how she should behave and react to labor and how she should interact with her newborn. If the woman, her family, and caregivers have similar views, little conflict in their values and expectations is likely. However, if these individuals hold markedly different views, they may be confused because each expects something different of the other (Darby, 2007).

Knowledge of the values and practices of cultural groups that the nurse encounters provides a framework to assess and care for the woman and her family, but within a culture, people are individuals. The nurse must assess the personal expectations and birth-related values of each woman and her family within this general framework. Aspects of cultural assessment for the intrapartum period might include:

Birth as an Experience

Childbirth is a physical and emotional experience. It is also an irrevocable event that changes a woman and her family forever. Families describe the births of children as they describe other pivotal events in life: marriages, anniversaries, religious events, and even deaths. Women often have specific expectations about the experience of childbirth. The more realistic a woman’s expectations about the birth are, the more likely she is to have a positive experience.

Nursing measures that increase a sense of control and mastery during birth help families perceive the birth as a positive event. Nursing measures to empower families include teaching them about their choices in childbirth in an unbiased way and supporting the choices they make.

Normal Labor

Theories of Onset

Labor begins when forces favoring continuation of pregnancy are overcome by forces favoring its end. The body’s preparation to give birth occurs gradually over the last few weeks of pregnancy. Although all reasons for initiation of labor are not known, factors that have a role in its onset include (Cunningham et al., 2010; Hall, 2011; Norwitz & Lye, 2009):

Premonitory Signs

Before spontaneous labor begins, women usually notice one or more of the following premonitory, or warning, signs that labor is near:

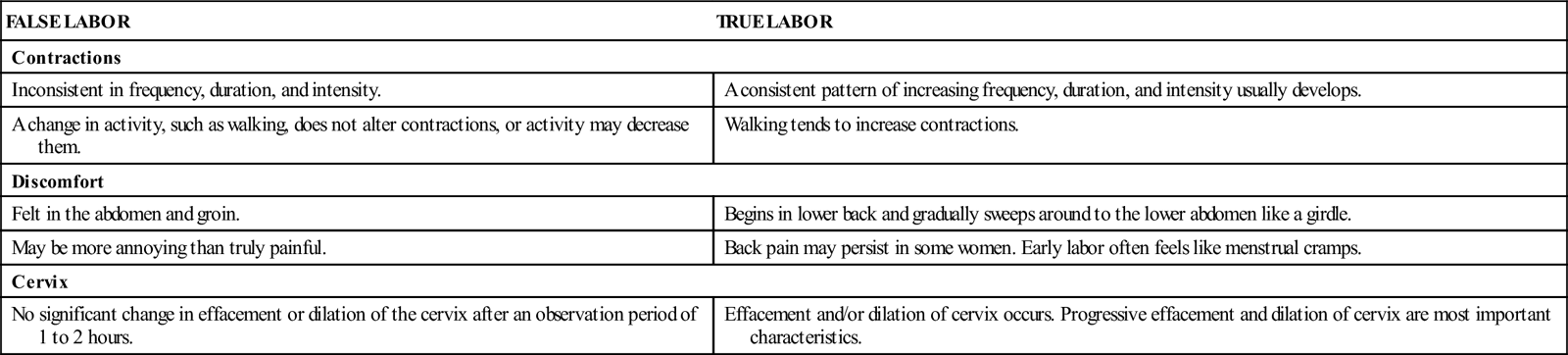

True Labor and False Labor

False labor, also called prodromal labor, is common because the time of spontaneous labor’s onset is rarely known and the onset is usually gradual. False labor often causes women to be disappointed when their symptoms are not “the real thing.” The term false labor may discourage a woman because she does not realize that these “false” contractions are simply preparation for the main event of true labor, rather than true labor itself.

Several characteristics distinguish true labor from false labor: contractions, discomfort, and cervical change. The best distinction between the two is that the contractions of true labor cause progressive changes in the cervix. Effacement and dilation occur with true labor contractions.

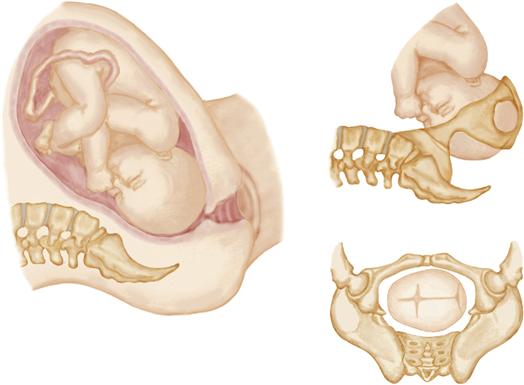

Mechanisms of Labor

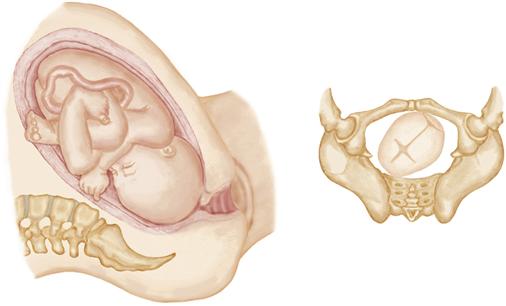

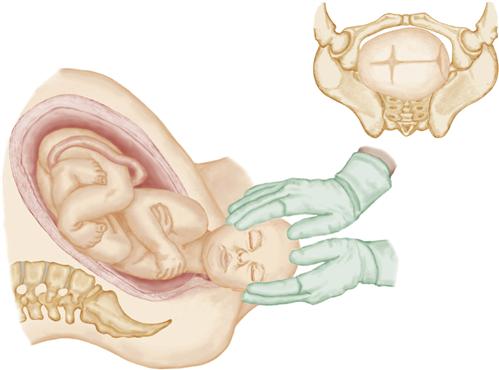

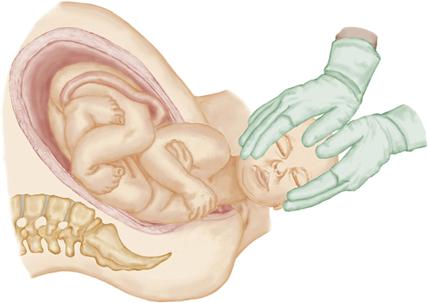

The mechanisms (cardinal movements) of labor occur as the fetus is moved through the pelvis during birth. The fetus undergoes several positional changes to adapt to the size and shape of

the mother’s pelvis at different levels (Figure 16-12). Although the mechanisms of labor are described separately in Figure 16-12, (pp. 330-331) some occur concurrently. In a vertex presentation, the mechanisms are:

• Descent of the fetal presenting part through the true pelvis.

• Flexion of the fetal head so that the smallest head diameters pass through the pelvis.

• Extension of the fetal head as it passes beneath the mother’s symphysis pubis.

DESCENT, ENGAGEMENT, AND FLEXION

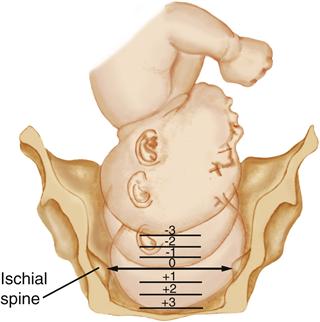

Descent of the fetus is a mechanism of labor that accompanies all the others. Without descent, none of the mechanisms will occur. Station

Station describes the descent of the fetal presenting part in relation to the level of the ischial spines. The level of the ischial spines is a zero station. Other stations are described with numbers representing the approximate number of centimeters above (negative numbers) or below (positive numbers) the ischial spines. As the fetus descends through the pelvis, the station changes from higher negative numbers (−3, −2, −1) to zero to higher positive numbers (+1, +2, +3, etc.). Sometimes the terms floating or ballottable may describe a fetal presenting part that is so high that it is easily displaced upward during abdominal or vaginal examination, similar to tossing a ball upward.

Engagement

Engagement occurs when the largest diameter of the fetal presenting part (normally the head) has passed the pelvic inlet and entered the pelvic cavity. Engagement is presumed to have occurred when the station of the presenting part is zero or lower. Engagement often takes place before onset of labor in nulliparous women. In many parous women and in some nulliparas, it does not occur until after labor begins.

Flexion

As the fetus descends, the fetal head is flexed farther as it meets resistance from the soft tissues of the pelvis. Head flexion presents the smallest anteroposterior diameter (suboccipitobregmatic) to the pelvis. Internal Rotation

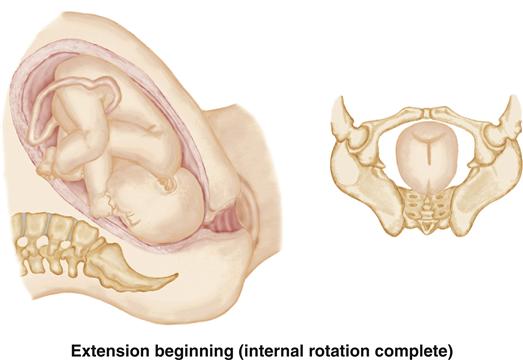

The fetus enters the pelvic inlet with the sagittal suture in a transverse or oblique orientation to the maternal pelvis because that is the widest inlet diameter. Internal rotation allows the longest fetal head diameter (the anteroposterior) to conform to the longest diameter of the maternal pelvis.

The longest pelvic outlet diameter is the anteroposterior. As the head descends to the level of the ischial spines, it gradually turns so that the fetal occiput is in the anterior of the pelvis (OA position, directly under the maternal symphysis pubis). When internal rotation is complete, the sagittal suture is oriented in the anteroposterior pelvic diameter (OA). Less commonly, the head may turn posteriorly so that the occiput is directed toward the mother’s sacrum (OP). EXTENSION

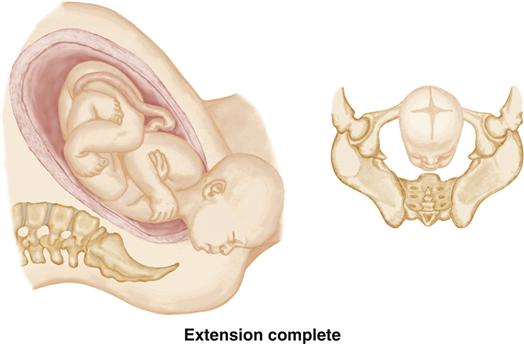

Because the true pelvis is shaped like a curved cylinder, the fetal head is directed posteriorly toward the rectum as it begins its descent. To negotiate the curve of the pelvis, the fetal head must change from an attitude of flexion to one of extension.

While still in flexion, the fetal head meets resistance from the tissues of the pelvic floor. At the same time, the fetal neck stops under the symphysis, which acts as a pivot. The combination of resistance from the pelvic floor and the pivoting action of the symphysis causes the fetal head to swing anteriorly, or extend, with each maternal pushing effort. The head is born in extension, with the occiput sliding under the symphysis and the face directed toward the rectum. The fetal brow, nose, and chin slide over the perineum as the head is born. EXTERNAL ROTATION

When the head is born with the occiput directed anteriorly, the shoulders must rotate internally so that they align with the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis.

After the head is born, it spontaneously turns to the same side as it was in utero as it realigns with the shoulders and back (through a process called restitution). The head then turns farther to that side in external rotation as the shoulders internally rotate and are positioned with their transverse diameter in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet. External rotation of the head accompanies internal rotation of the shoulders. EXPULSION

Expulsion occurs first as the anterior, then the posterior, shoulder passes under the symphysis. After the shoulders are born, the rest of body follows.

The mechanisms of labor are different in presentations other than the vertex, but the reason is the same: effective use of available space in the maternal pelvis.

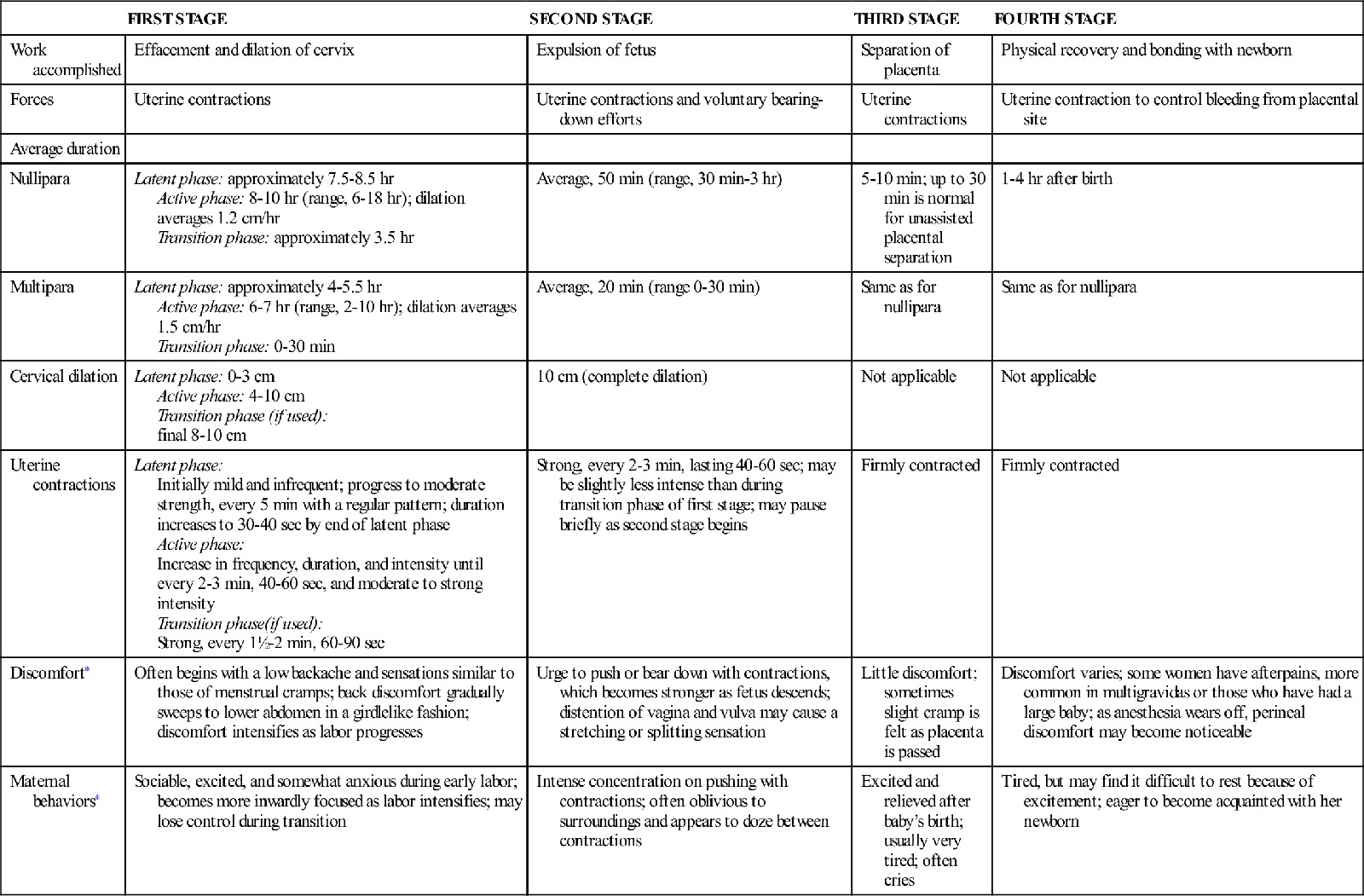

Stages and Phases of Labor

Each stage and phase of labor has qualities that set it apart from the others. Individual women vary in their labor patterns and responses to labor. Table 16-1 provides details of the characteristics of each stage of labor. Use of regional anesthetics, such as the epidural block, is likely to modify the typical maternal behaviors. Also, labor that is induced or augmented often differs from spontaneous labor.

TABLE 16-1

CHARACTERISTICS OF NORMAL LABOR

| FIRST STAGE | SECOND STAGE | THIRD STAGE | FOURTH STAGE | |

| Work accomplished | Effacement and dilation of cervix | Expulsion of fetus | Separation of placenta | Physical recovery and bonding with newborn |

| Forces | Uterine contractions | Uterine contractions and voluntary bearing-down efforts | Uterine contractions | Uterine contraction to control bleeding from placental site |

| Average duration | ||||

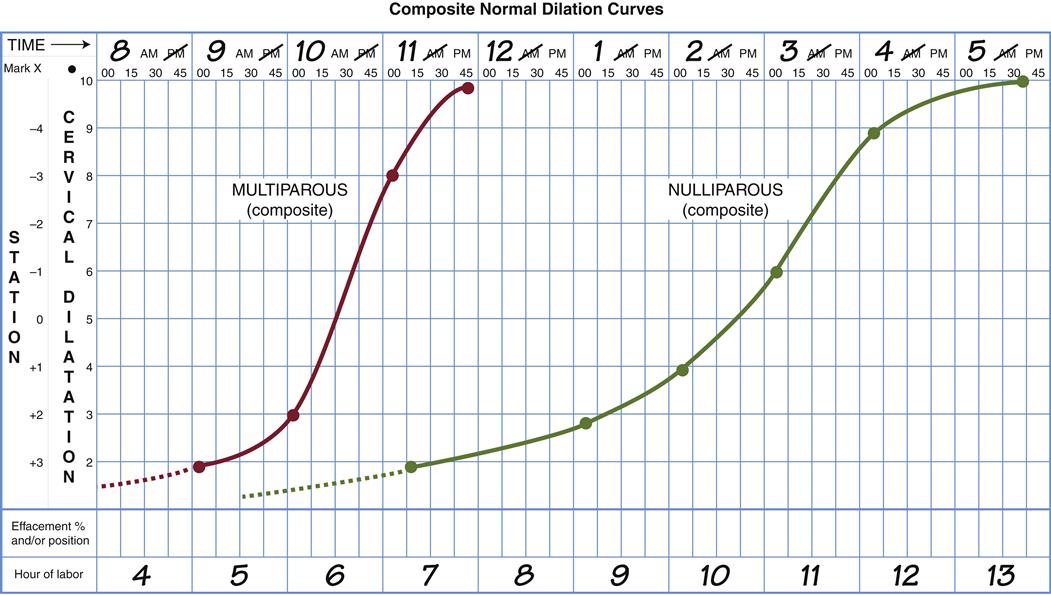

| Nullipara | Latent phase: approximately 7.5-8.5 hr Active phase: 8-10 hr (range, 6-18 hr); dilation averages 1.2 cm/hr Transition phase: approximately 3.5 hr | Average, 50 min (range, 30 min-3 hr) | 5-10 min; up to 30 min is normal for unassisted placental separation | 1-4 hr after birth |

| Multipara | Latent phase: approximately 4-5.5 hr Active phase: 6-7 hr (range, 2-10 hr); dilation averages 1.5 cm/hr Transition phase: 0-30 min | Average, 20 min (range 0-30 min) | Same as for nullipara | Same as for nullipara |

| Cervical dilation | Latent phase: 0-3 cm Active phase: 4-10 cm Transition phase (if used): final 8-10 cm | 10 cm (complete dilation) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Uterine contractions | Latent phase: Initially mild and infrequent; progress to moderate strength, every 5 min with a regular pattern; duration increases to 30-40 sec by end of latent phase Active phase: Increase in frequency, duration, and intensity until every 2-3 min, 40-60 sec, and moderate to strong intensity Transition phase(if used): Strong, every 1½-2 min, 60-90 sec | Strong, every 2-3 min, lasting 40-60 sec; may be slightly less intense than during transition phase of first stage; may pause briefly as second stage begins | Firmly contracted | Firmly contracted |

| Discomfort∗ | Often begins with a low backache and sensations similar to those of menstrual cramps; back discomfort gradually sweeps to lower abdomen in a girdlelike fashion; discomfort intensifies as labor progresses | Urge to push or bear down with contractions, which becomes stronger as fetus descends; distention of vagina and vulva may cause a stretching or splitting sensation | Little discomfort; sometimes slight cramp is felt as placenta is passed | Discomfort varies; some women have afterpains, more common in multigravidas or those who have had a large baby; as anesthesia wears off, perineal discomfort may become noticeable |

| Maternal behaviors∗ | Sociable, excited, and somewhat anxious during early labor; becomes more inwardly focused as labor intensifies; may lose control during transition | Intense concentration on pushing with contractions; often oblivious to surroundings and appears to doze between contractions | Excited and relieved after baby’s birth; usually very tired; often cries | Tired, but may find it difficult to rest because of excitement; eager to become acquainted with her newborn |

∗Maternal discomfort and behaviors often vary with pain-relief method chosen.

From Hobel, C. J., & Zakowski, M. (2010). Normal labor, delivery, and postpartum care. In N. F. Hacker, J. C. Gambone, & C. J. Hobel (Eds.), Hacker & Moore’s essentials of obstetrics and gynecology (5th ed., pp. 91-118). Philadelphia: Saunders; Kilpatrick, S. J., & Laros, R. K. (1989). Characteristics of normal labor. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 74(1), 85-87; Simpson, K. R. (2008). Labor and birth. In K. R. Simpson & P.A. Creehan (Eds.), AWHONN’s perinatal nursing (3rd ed., pp. 300-388). Philadelphia: Lippincott.

First Stage of Labor

Cervical effacement and dilation occur in the first stage of labor, or stage of dilation. It begins with the onset of true labor contractions and ends with complete dilation (10 cm) and effacement (100%) of the cervix. The first stage of labor is the longest for both nulliparous and parous women. Labor progress may be plotted on a graph, often called a Friedman curve (Figure 16-13, p. 333). However, the Friedman curve cannot be the only measure of normal progress with today’s technology. Current measures of maternal and fetal well-being, such as fetal monitoring, provide added information about whether a longer labor duration should be ended or allowed to continue.

First-stage labor differs from the other stages because it has three phases: latent (early), active, and transition. Each phase is characterized by typical maternal behaviors. These behaviors vary with the woman’s preparation, use of coping skills, and analgesia.

Latent Phase

The latent, or early, phase lasts from the beginning of labor until about 3 to 5 cm of cervical dilation. Its length varies among women. Despite being called latent, cervical effacement and subtle fetal position change occur during this phase, preparing for more rapid changes of active labor. The woman is usually sociable and excited during this early phase of labor.

Active Phase

The cervix dilates more rapidly as the woman enters the active phase, between about 4 cm and 6 cm. Research has demonstrated safety in a slower transition between latent and active labor than usually accepted in women in spontaneous labor (Zhang, Landry, Branch, et al., 2010). Effacement and dilation of the cervix are completed. Internal rotation occurs as the fetus descends in the pelvis during active labor. Discomfort usually increases as the pace of labor picks up. Transition may be used to describe the intense contractions of fetal descent and final cervical dilation, about 7 or 8 cm to complete.

Bloody show often increases with completion of cervical dilation. Transition is a short but intense phase, with very strong contractions. The woman may have an urge to push down during contractions as the fetal presenting part reaches her pelvic floor. Leg tremors, nausea, and vomiting are common as second stage nears.

The woman becomes more anxious and may feel irritable and helpless as the contractions intensify. The sociability of early labor is gone, replaced with a serious, inward focus. Her partner may be confused because actions that were helpful just a short time before now bother her.

Second Stage of Labor

The second stage (expulsion) begins with complete (10 cm) dilation and full (100%) effacement of the cervix and ends with the birth of the baby. As the fetus descends, pressure of the presenting part on the rectum and the pelvic floor causes the mother to have an involuntary pushing response. She may say that she needs to have a bowel movement or “The baby’s coming” or “I have to push.” Her voluntary pushing efforts augment involuntary uterine contractions. As the fetus descends low in the pelvis and the vulva distends with crowning of the fetal head, she may feel a sensation of stretching or splitting even if no trauma occurs.

Contractions are strong, but the woman may feel more in control because she is actively completing the process by pushing with them. “Labor” describes the second stage well. The woman exerts intense effort to push her baby out. Between contractions she may be oblivious to her surroundings and may appear asleep. She feels tremendous relief and excitement as the second stage ends with the birth of her baby.

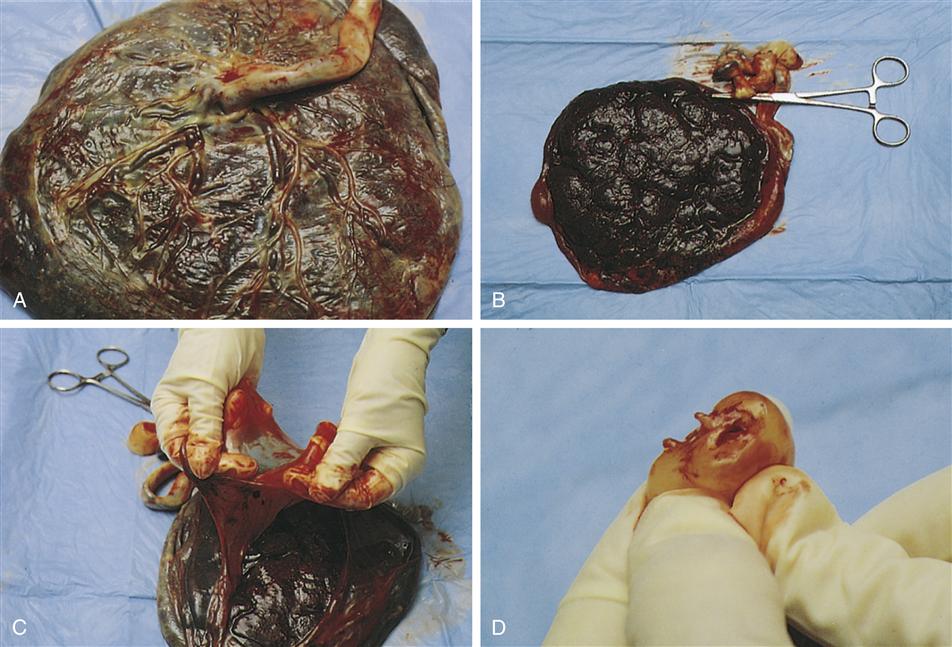

Third Stage of Labor

The third (placental) stage begins with the birth of the baby and ends with the expulsion of the placenta (Figure 16-14). When the infant is born, the uterine cavity becomes much smaller. The reduced size decreases the size of the placental site, causing the placenta to separate from the uterine wall. Four signs suggest placenta separation:

• The uterus has a spherical shape.

• The cord descends further from the vagina.

• A gush of blood appears as blood trapped behind the placenta is released.

The placenta may be expelled in one of two ways. In the more common Schultze mechanism, the placenta is expelled with the shiny, fetal side first (see Figure 16-14, A). The Duncan mechanism is less common, with the rough maternal side presenting (see Figure 16-14, B).

The uterus must contract firmly and remain contracted after the placenta is expelled to compress open vessels at the implantation site. Inadequate uterine contraction after birth may result in hemorrhage.

Pain during the third stage of labor results from uterine contractions and brief stretching of the cervix as the placenta passes through it.

Fourth Stage of Labor

The fourth stage of labor is the stage of physical recovery for the mother and infant. It lasts from the delivery of the placenta through the first 1 to 4 hours after birth.

Immediately after birth, the firmly contracted uterus can be palpated through the abdominal wall as a firm, rounded mass about 10 to 15 cm (4 to 6 in) in diameter at or below the level of the umbilicus. The uterus is larger when the infant is large or the mother is a multipara. Uterine size is larger in the women who delivered twins or more at or near term.

The vaginal drainage during the fourth stage is lochia rubra, which consists mostly of blood. Small clots may also be present. See Chapter 20 for more information about lochia.

Many women have a chill after birth. The chill lasts for about 20 minutes and subsides spontaneously. A warm blanket, hot drink, or soup may help shorten the chill and make the woman more comfortable.

Discomfort during the fourth stage usually results from birth trauma or afterpains. Ice packs on the perineum limit discomfort and hematoma formation.

Afterpains are uterine contractions similar to menstrual cramps that occur after birth as the uterus begins its return to the prepregnancy state. The discomfort is similar to that of menstrual cramps. Afterpains are more intense in multiparas, in women who breastfeed, in women who have large babies or other causes of uterine overdistention during pregnancy, or when something interferes with uterine contraction, such as a full bladder or a blood clot that remains in the uterus.

The mother is simultaneously excited and tired after birth. She may be exhausted but too full of nervous energy to rest. The fourth stage of labor is an ideal time for bonding of the new family because the interest of both parents and newborn is high. It is also the best time to start breastfeeding if no maternal or infant problems are present. The baby is alert and seeks to make eye contact with the new parents, giving powerful reinforcement for the parents’ attachment to their newborn.

Duration of Labor

The total duration of labor is different for women who have never given birth and for those who have previously given birth vaginally. The parous woman usually delivers more quickly than does the nulliparous woman. Women, however, are individuals. Some nulliparas progress through labor quickly, whereas labor for some parous women resembles that of women who have never given birth. A woman who experienced a long labor with her first child may not have a long labor with every baby. If she has a history of rapid labor, however, later births are often rapid as well.

Nursing Care During Labor and Birth

Admission to the Birth Center

During the last trimester, the woman needs to know when she should go to the hospital or birth center. Nurses teach women differences between false labor and true labor and offer guidelines for going to the birth center. Not everyone has a typical labor, so a woman should be encouraged to go to the birth center if she is uncertain or has other concerns.

Nursing Responsibilities during Admission

The nurse has two priorities when the woman arrives at the birth center: (1) establishing a therapeutic relationship while (2) assessing the condition of the mother and fetus.

Establishing a Therapeutic Relationship

Making the Family Feel Welcome

A family’s first impression influences how family members feel about the quality of the birth experience. Even if the unit is busy, the nurse should communicate interest, friendliness, caring, and competence. Families understand if the nurse is busy; they do not understand rudeness or insensitivity to their needs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree