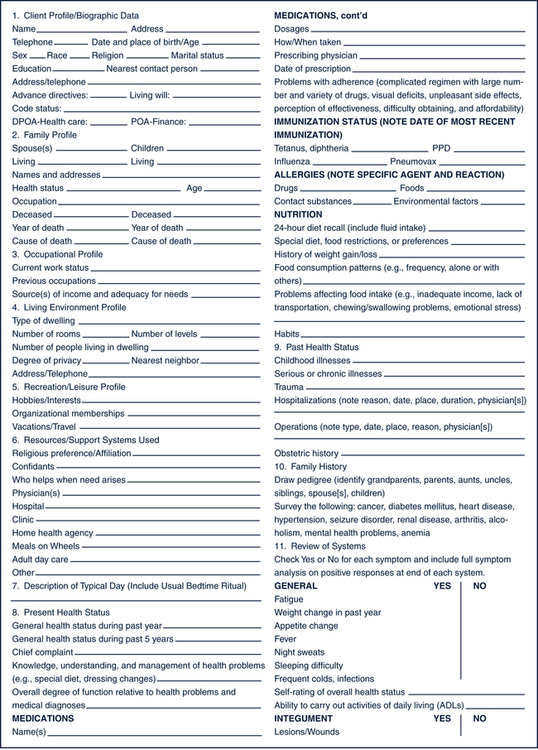

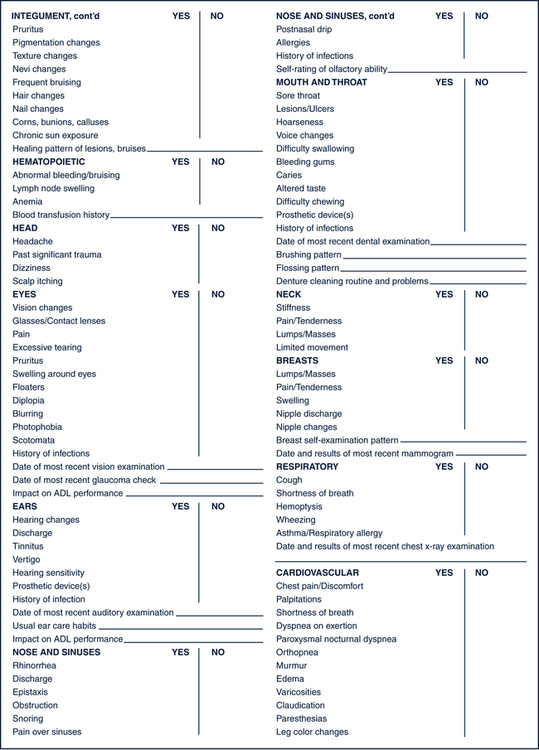

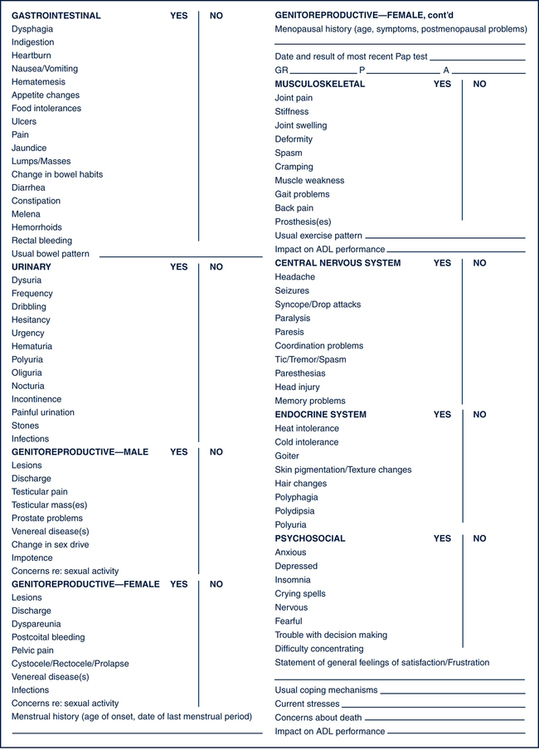

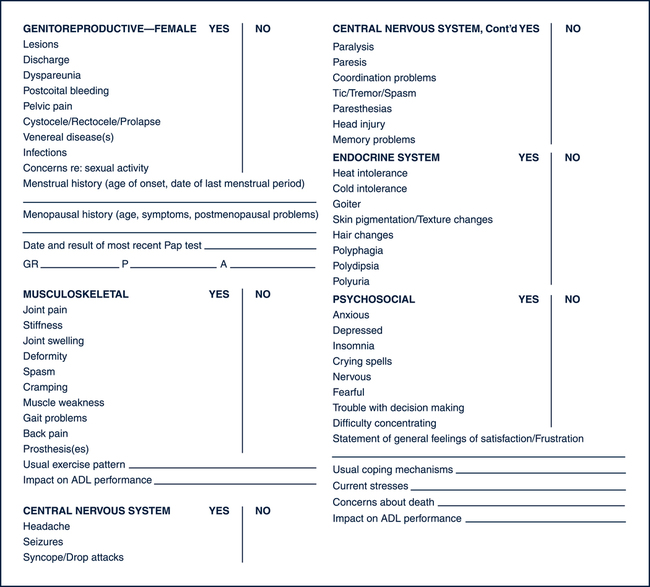

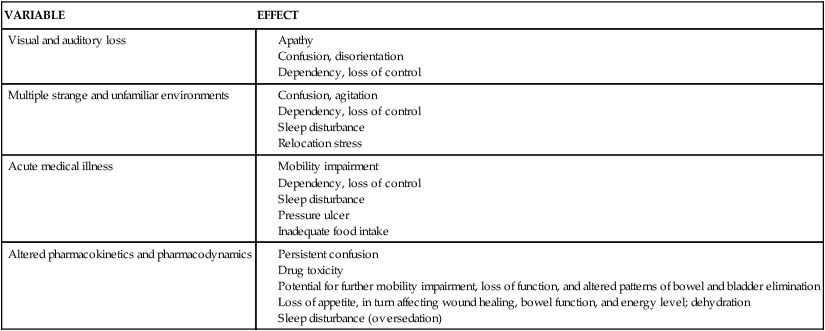

Sue E. Meiner, EdD, APRN, BC, GNP On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Explain the interrelationship between the physical and psychosocial aspects of aging as it affects the assessment process. 2. Describe how the nature of illness presentation, changes in homeostatic mechanisms, and the lack of normative standards for older adults affect the assessment process. 3. Compare and contrast the clinical presentation of delirium and dementia. 4. Describe the assessment modifications that may be necessary when assessing older adults. 5. Describe strategies and techniques to ensure collection of relevant and comprehensive health histories for older adults. 6. Identify the basic components of health histories for older adults. 7. List the principles to observe when conducting physical examinations of older adults. 8. Explain the rationale for assessing functional status in older adults. 9. Describe the elements of a functional assessment. 10. Describe the basic components of a mental status assessment. 11. Discuss the rationale for conducting affective assessments on older adults. 12. Explain the rationale for assessing social function in older adults. 13. Conduct a comprehensive health assessment on an older adult client. A nursing focus evolves from an awareness and understanding of the purpose of nursing. This purpose was defined in the 1980 American Nurses Association (ANA) publication, Nursing: A Social Policy Statement, as “the diagnosis and treatment of human responses to actual or potential health problems.” In 1995 the ANA developed Nursing’s Social Policy Statement, which elaborated on the above purpose of nursing based on the growth of nursing science “and its integration with the traditional knowledge base for diagnosis and treatment of human responses to health and illness.” Although providing no specific definition of nursing, this policy statement cited three “essential features of contemporary nursing practice” that are common to most definitions: • Attention to the full range of human experiences and responses to health and illness without restriction to a problem-focused orientation. • Integration of objective data with knowledge gained from an understanding of the client or group’s subjective experience. • Application of scientific knowledge to the processes of diagnosis and treatment. Provision of a caring relationship that facilitates health and healing (ANA, 1995). It is clear from these elements that the nurse collects subjective and objective data about the client to assist in determining the client’s response to health and illness. A comprehensive, nursing-focused assessment of these responses establishes a database about a client’s ability to meet the full range of physical and psychosocial needs. Client responses that reveal an inability to satisfactorily meet these needs indicate a need for nursing care, or the “caring relationship that facilitates health and healing” (ANA, 1995). In 2004, Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice entered another review process that resulted in the current ANA expectations of the professional role within which all registered nurses must practice. The ANA charged those in the nursing profession to incorporate the standards into practice settings across the country. According to the ANA (2004), “The goal is to improve the health and well-being of all individuals, communities, and populations through the significant and visible contributions of registered nurses utilizing standards-based practice.” Table 4–1 depicts the many serious consequences of the interacting physical and psychosocial factors in this case. A word of caution is warranted: Undue emphasis should not be placed on individual weaknesses. In fact, it is imperative that the gerontologic nurse search for the client’s strengths and abilities and build the plan of care on these. However, in a situation such as that of Mrs. K, the nurse should be aware of the potential for the consequences illustrated here. A single problem is not likely because multiple conditions are often superimposed. In addition, the cause of one problem is often best understood in view of the accompanying problems. Careful consideration, then, of the interrelationships between physical and psychosocial aspects in every client situation is essential. TABLE 4–1 EFFECT OF SELECTED VARIABLES ON FUNCTIONAL STATUS Adapted from Lueckenotte AG: Pocket guide to gerontologic assessment, ed 3, St Louis, 1998, Mosby. The immune system, as the body’s major defense against illness and disease, has a decreased ability to provide protection with aging (see Chapter 16). Although scientists have attempted to identify which age-related immune system changes cause the decline in immunocompetence, it has been difficult to do so because immunocompetence is affected by multiple factors. The important point is that older adults often encounter profound and repeated losses; the time between the occurrences of these losses is often short, resulting in an inadequate period for resolution and return to a baseline state. Older adults have less ability than younger people to cope with assaults such as infection, blood loss, a high-technology environment, or loss of a significant person (see Chapter 20). The nurse should therefore assess older adults for the presence of physical and psychosocial stressors and their physical and emotional manifestations. One area where scientific study is changing how health care providers interpret normal versus abnormal status is that of laboratory values. Relying on established norms for laboratory values when analyzing older adults’ assessment data could lead to incorrect conclusions. Fasting blood glucose of 80 mg/100 mL may be within the normal range for a young adult, but an older person with that same level may experience symptoms of hypoglycemia. Polypharmacy and the multiplicity of illness and disease are only two variables that may affect laboratory data interpretation for older adults (see Chapters 21 and 22). In addition, there are no definitive aging norms for many pathologic conditions. For example, controversy has existed over what constitutes isolated systolic hypertension in older people. Is a high systolic pressure simply a function of age, or does it require treatment? The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VII) states that cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in older people have been reduced with antihypertensive drug therapy (National High Blood Pressure Education Program, 2003). However, Moser (2007) identified that the lowering of systolic hypertension using drug therapy (diuretic or beta-blocker drugs) made more of a positive difference in the outcome than any specific antihypertensive medication(s). As more studies are conducted in this and other areas, norms for older adults will continue to be redefined. The atypical presentation of illness can be displayed in various ways. For example, the signs and symptoms may be modified in some way, as in the case of pneumonia, when older adults may exhibit dry coughs instead of the classic productive coughs. Also, the presenting signs and symptoms may be totally unrelated to the actual problem, such as the confusion that may accompany a urinary tract infection. Finally, the expected signs and symptoms may not be present at all, as in the case of a myocardial infarction that includes no chest pain (Table 4–2). All these atypical presentations challenge the nurse to conduct careful and thorough assessments and analyses of symptoms to ensure appropriate treatment. Again, a simple and safe strategy is to compare the presenting signs and symptoms with the older adult’s normal baselines. TABLE 4–2 Modified from Henderson ML: Altered presentations. Am J Nurs 15:1104, 1986. As can be seen in Table 4–2, delirium is one of the most common, atypical presentations of illness in older adults, representing a wide variety of potential problems. Confusion, mental status changes, cognitive changes, and delirium are some of the terms used to describe one of the most common manifestations of illness in old age. Foreman (1986) advocates use of the term acute confusional state (ACS) to describe “an organic brain syndrome characterized by transient, global cognitive impairment of abrupt onset and relatively brief duration, accompanied by diurnal fluctuation of simultaneous disturbances of the sleep–wake cycle, psychomotor behavior, attention, and affect.” Unfortunately, the ageist views of many health care providers cause them to believe that an ACS is a normal, expected outcome of aging, thus robbing older adults of complete and thorough workups of this syndrome. The nurse as an advocate for older persons may need to remind other team members that a sudden change in cognitive function is often the result of illness, not aging. Knowing older adults’ baseline mental status is essential to avoid overlooking a serious illness manifesting itself as an ACS. Box 4–1 outlines the multivariate causes of an ACS that the nurse must consider during assessment. One of the more challenging aspects of older adult assessment is distinguishing a reversible ACS from irreversible cognitive changes such as those seen in dementia and related disorders. In contrast to the characteristics of an ACS noted previously, dementia is a global, sustained deterioration of cognitive function in an alert client. Other diagnostic features of dementia include memory impairment and one or more of the following cognitive disturbances: aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or disturbance in executive functioning (e.g., planning, organizing, sequencing, abstracting) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Primary dementias include senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, Lewy body disease, Pick’s disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and multiinfarct dementia. Secondary dementias that have the same presenting symptoms but that are often reversible with early diagnosis include normal pressure hydrocephalus, intracranial masses or lesions, pseudodementia, and Parkinson’s dementia. Table 4–3 depicts the distinguishing features of an ACS and dementia. See Chapter 29 for a complete description of these primary and secondary dementing diseases. TABLE 4–3 DIFFERENTIATING DEMENTIA AND AN ACUTE CONFUSIONAL STATE (ACS) Modified from Foreman MD: Acute confusional states in hospitalized elderly: a research dilemma, Nurs Res 35(1):34, 1986. • Provide adequate space, particularly if the client uses a mobility aid. • Minimize noise and distraction such as those generated by a television, radio, intercom, or other nearby activity. • Set a comfortable, sufficiently warm temperature and ensure there are no drafts. • Use diffuse lighting with increased illumination; avoid directional or localized light. • Avoid glossy or highly polished surfaces, including floors, walls, ceilings, and furnishings. • Place the client in a comfortable seating position that facilitates information exchange. • Maintain proximity to a bathroom. • Keep water or other preferred fluids available. • Provide a place to hang or store garments and belongings. • Plan the assessment, taking into account the older adult’s energy level, pace, and adaptability. More than one session may be necessary to complete the assessment. • Be patient, relaxed, and unhurried. • Allow the client plenty of time to respond to questions and directions. • Maximize the use of silence to allow the client time to collect thoughts before responding. • Be alert to signs of increasing fatigue such as sighing, grimacing, irritability, leaning against objects for support, dropping of the head and shoulders, and progressive slowing. • Conduct the assessment during the client’s peak energy time. • Assess more than once and at different times of the day. • Measure performance under the most favorable of conditions. • Take advantage of natural opportunities that would elicit assets and capabilities; collect data during bathing, grooming, and mealtime. • Ensure that assistive sensory devices (glasses, hearing aid) and mobility devices (walker, cane, prosthesis) are in place and functioning correctly. • Interview family, friends, and significant others who are involved in the client’s care to validate assessment data. • Use body language, touch, eye contact, and speech to promote the client’s maximum degree of participation. • Be aware of the client’s emotional state and concerns; fear, anxiety, and boredom can lead to inaccurate assessment conclusions regarding functional ability. Although a number of formats exist for the nursing health history, all have similar basic components (Fig. 4–1). In addition, the nursing health history for the older adult should include assessment of functional, cognitive, affective, and social well-being. Specific tools for the collection of these data are addressed later in this chapter. Attitude is a feeling, value, or belief about something that determines behavior. If the nurse has an attitude that characterizes older people as less healthy and alert and more dependent, then the interview structure will reflect this attitude. For example, if the nurse believes that dependence in self-care normally accompanies advanced age, the client will not be questioned about strengths and abilities. The resulting inaccurate functional assessment will do little to promote client independence. Myths and stereotypes about older adults also can affect the nurse’s questioning. For example, believing that older people do not participate in sexual relationships can result in the nurse’s failure to interview the client about sexual health matters (see Chapter 13). The nurse’s own anxiety and fear of personal aging, as well as a lack of knowledge regarding older people, contribute to commonly held negative attitudes, myths, and stereotypes about older people. Gerontologic nurses have a responsibility to themselves and to their older adult clients to improve their understanding of the aging process and aging people.

Gerontologic Assessment

Interrelationship Between Physical and Psychosocial Aspects of Aging

VARIABLE

EFFECT

Visual and auditory loss

Multiple strange and unfamiliar environments

Acute medical illness

Altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

Nature of Disease and Disability and their Effects on Functional Status

Decreased Efficiency of Homeostatic Mechanisms

Lack of Standards for Health and Illness Norms

Altered Presentation of and Response to Specific Diseases

PROBLEM

CLASSIC PRESENTATION IN YOUNG PATIENT

PRESENTATION IN ELDERLY PATIENTS

Urinary tract infection

Dysuria, frequency, urgency, nocturia

Dysuria often absent; frequency, urgency, nocturia sometimes present. Incontinence, delirium, falls, and anorexia are other signs.

Myocardial infarction

Severe substernal chest pain, diaphoresis, nausea, dyspnea

Sometimes no chest pain or atypical pain location such as in jaw, neck, shoulder, epigastric area. Dyspnea may or may not be present. Other signs are tachypnea, arrhythmia, hypotension, restlessness, syncope, and fatigue/weakness. A fall may be a prodrome.

Bacterial pneumonia

Cough productive of purulent sputum, chills and fever, pleuritic chest pain, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count

Cough may be productive, dry, or absent; chills and fever and/or elevated WBCs also may be absent. Tachypnea, slight cyanosis, delirium, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and tachycardia may be present.

Congestive heart failure

Increased dyspnea (orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea), fatigue, weight gain, pedal edema, nocturia, bibasilar crackles

All the manifestations of young adult and/or anorexia, restlessness, delirium, cyanosis, and falls. Cough.

Hyperthyroidism

Heat intolerance, fast pace, exophthalmos, increased pulse, hyperreflexia, tremor

Slowing down (apathetic hyperthyroidism), lethargy, weakness, depression, atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure.

Hypothyroidism

Weakness, fatigue, cold intolerance, lethargy, skin dryness and scaling, constipation

Often presents without overt symptoms; majority of cases are subclinical. Delirium, dementia, depression/lethargy, constipation, weight loss, and muscle weakness/unsteady gait are common.

Depression

Dysphoric mood and thoughts, withdrawal, crying, weight loss, constipation, insomnia

Any of classic symptoms may or may not be present. Memory and concentration problems, cognitive and behavioral changes, increased dependency, anxiety, and increased sleep. Muscle aches, abdominal pain or tightness, flatulence, nausea and vomiting, dry mouth, and headaches. Be alert for congestive heart failure, diabetes, cancer, infectious diseases, and anemia. Cardiovascular agents, anxiolytics, amphetamines, narcotics, and hormones can also play a role.

Cognitive Impairment

CLINICAL FEATURE

ACS

DEMENTIA

Onset

Acute/subacute; depends on cause; often occurs at twilight

Chronic, generally insidious; depends on cause

Course

Short; diurnal fluctuations in symptoms; worse at night, dark, and on awakening

Long; no diurnal effects; symptoms progressive yet relatively stable over time

Duration

Hours to less than 1 month

Months to years

Awareness

Fluctuates, generally reduced

Generally clear

Alertness

Fluctuates—reduced or increased

Generally normal

Attention

Impaired, often fluctuates

Generally normal

Orientation

Fluctuates in severity, generally impaired

May be impaired

Memory

Recent and immediate memory impaired; unable to register new information or recall recent events

Recent and remote memory impaired; loss of recent memory is first sign; some loss of common knowledge

Thinking

Disorganized, distorted, fragmented, slow, or accelerated

Difficulty with abstraction and word finding

Perception

Distorted, illusions, delusions, or hallucinations

Misperceptions often absent

Sleep–wake cycle

Disturbed, cycle reversed

Fragmented

Tailoring the Nursing Assessment to the Older Person

The Health History

The Interviewer

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gerontologic Assessment

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access