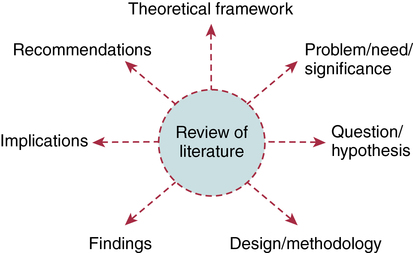

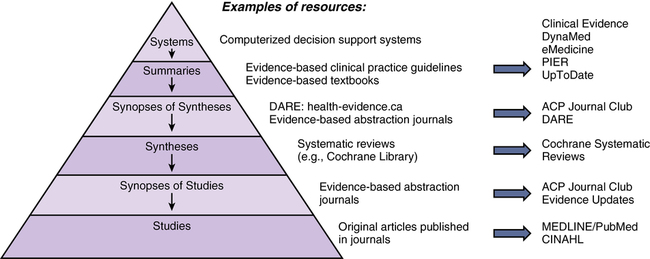

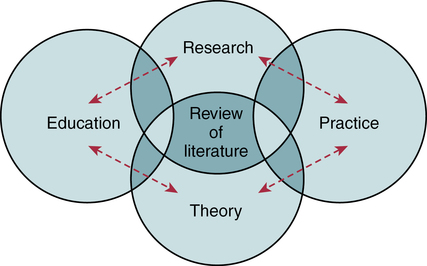

CHAPTER 3 Stephanie Fulton and Barbara Krainovich-Miller After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: • Discuss the relationship of the literature review to nursing theory, research, and practice. • Differentiate the purposes of the literature review from the perspective of the research investigator and the research consumer. • Discuss the use of the literature review for quantitative designs and qualitative methods. • Discuss the purpose of reviewing the literature for developing evidence-based practice and quality improvement projects. • Differentiate between primary and secondary sources. • Compare the advantages and disadvantages of the most commonly used electronic databases for conducting a literature review. • Identify the characteristics of an effective electronic search of the literature. • Critically read, appraise, and synthesize sources used for the development of a literature review. • Apply critiquing criteria for the evaluation of literature reviews in research studies. • Discuss the role of the “6S” hierarchy of pre-appraised evidence for application to practice. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critiquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. Your critical appraisal, also called a critique of the literature, is an organized, systematic approach to evaluating a research study or group of studies using a set of standardized, established critical appraisal criteria to objectively determine the strength, quality, quantity, and consistency of evidence provided by literature to determine its applicability to research, education, or practice. The literature review of a published study generally appears near the beginning of the report. It provides an abbreviated version of the complete literature review conducted by a researcher and represents the building blocks, or framework, of the study. Therefore, the literature review, a systematic and critical appraisal of the most important literature on a topic, is a key step in the research process that provides the basis of a research study. The links between theory, research, education, and practice are intricately connected; together they create the knowledge base for the nursing discipline as shown in Figure 3-1. The purpose of this chapter is to introduce you to the literature review as it is used in research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement projects. It provides you with the tools to (1) locate, search for, and retrieve individual research studies, systematic reviews (see Chapters 1, 9, 10, and 19), and other documents (e.g., clinical practice guidelines); (2) differentiate between a research article and a conceptual article or book; (3) critically appraise a research study or group of research studies; and (4) differentiate between a research article and a conceptual article or book. These tools will help you develop your research consumer competencies and prepare your academic papers and evidence-based practice and quality improvement projects. The overall purpose of the literature review in a research study is to present a strong knowledge base for the conduct of the study. It is important to understand when reading a research article that the researcher’s main goal when developing the literature review is to develop the knowledge foundation for a sound study and to generate research questions and hypotheses. A literature review is essential to all steps of the quantitative and qualitative research processes. From this perspective, the review is broad and systematic, as well as in-depth. It is a critical collection and evaluation of the important literature in an area. From a researcher’s perspective, the objectives in Box 3-1 (items 1-6) direct the questions the researcher asks while reading the literature to determine a useful research question(s) or hypothesis(es) and how best to design a study. Objectives 7 through 10 are applicable to the consumer of research perspective discussed later in the chapter. • Theoretical or conceptual framework: A literature review reveals concepts and/or theories or conceptual models from nursing and other disciplines that can be used to examine problems. The framework presents the context for studying the problem and can be viewed as a map for understanding the relationships between or among the variables in quantitative studies. The literature review provides rationale for the variables and explains concepts, definitions, and relationships between or among the independent and dependent variables used in the theoretical framework of the study (see Chapter 4). However, in many research articles the literature review may not be labeled. For example, Thomas and colleagues (2012) did not label the literature review, yet the beginning section of the article is clearly the literature review (see Appendix A). • Primary and secondary sources: The literature review should mainly use primary sources; that is, research articles and books by the original author. Sometimes it is appropriate to use secondary sources, which are published articles or books that are written by persons other than the individual who conducted the research study or developed the theory (Table 3-1). TABLE 3-1 EXAMPLES OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SOURCES • Research question and hypothesis: The literature review helps to determine what is known and not known; to uncover gaps, consistencies, or inconsistencies; and/or to disclose unanswered questions in the literature about a subject, concept, theory, or problem that generate, or allow for refinement of, research questions and/or hypotheses. • Design and method: The literature review exposes the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies in terms of designs and methods and helps the researcher choose an appropriate design and method, including sampling strategy type and size, data collection methods, setting, measurement instruments, and effective data analysis method. Often, because of journal space limitations, researchers include only abbreviated information about this in their article. • Outcome of the analysis (i.e., findings, discussion, implications, recommendations): The literature review is used to help the researcher accurately interpret and discuss the results/findings of a study. In the discussion section of a research article, the researcher returns to the research studies, theoretical articles, or books presented earlier in the literature review and uses this literature to interpret and explain the study’s findings (see Chapters 16 and 17). For example, Alhusen and colleagues’ (2012) discussion section noted that “the findings of this study highlight the significance of MFA as predictor of neonatal health and wellbeing, and, potentially, health care costs” (see Appendix B). The literature review is also useful when considering implications of the research findings for making recommendations for practice, education, and further research. Alhusen and colleagues also stated in the discussion section that “future researchers should test culturally relevant interventions aimed at improving the maternal-fetal relationship.” Figure 3-2 relates the literature review to all aspects of the quantitative research process. In contrast to the styles of quantitative studies, literature reviews of qualitative studies are usually handled differently (see Chapters 5 to 7) but often, when published, will appear at the beginning of the article. In qualitative studies, often little is known about the topic under study, and thus literature reviews may appear abbreviated. Qualitative researchers use the literature review in the same manner as quantitative researchers to discuss the findings of the study. From the perspective of the research consumer, you conduct an electronic database search of your clinical problem and appraise the studies to answer a clinical question or solve a clinical problem. Therefore, you search the literature widely and gather multiple resources to answer your question using an evidence-based practice approach. This search focuses you on the first three steps of the evidence-based practice process: asking clinical questions, identifying and gathering evidence, and critically appraising and synthesizing the evidence or literature. Objectives 7 through 10 in Box 3-1 specifically reflect the purposes of a literature review for these projects. As a student or practicing nurse you may be asked to generate a clinical question for an evidence-based practice project and search for, retrieve, and critically appraise the literature to identify the “best available evidence” that provides the answer to a clinical question and informs your clinical decision making using the evidence-based practice process outlined in Chapter 1. A clear and precise articulation of a question is critical to finding the best evidence. Evidence-based questions may sound like research questions, but they are questions used to search the existing literature for answers. The evidence-based practice process uses the PICO format to generate well-built clinical questions (Haynes et al., 2006; Richardson, 1995). For example, students in an adult health course were asked to generate a clinical question related to health promotion for older women using the PICO format (see Chapter 2). The PICO format is as follows: P Problem/patient population; specifically defined group I Intervention; what intervention or event will be studied? C Comparison of intervention; with what will the intervention be compared? P Postmenopausal women with osteopenia (Age is part of the definition.) I Regular exercise program (How often is regular? Weekly? Twice a week?) O Prevention of osteoporosis (How and when was this measured?) Their assignment required that they do the following: • Search the literature using electronic databases (e.g., Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL via EBSCO], MEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) for the background information that enabled them to identify the significance of osteopenia and osteoporosis as a women’s health problem. • Identify systematic reviews, practice guidelines, and individual research studies that provided the “best available evidence” related to the effectiveness of regular exercise programs on prevention of osteoporosis. • Critically appraise the information gathered based on standardized critical appraisal criteria and tools (see Chapters 1, 11, 19, and 20). • Synthesize the overall strengths and weaknesses of the evidence provided by the literature. • Draw a conclusion about the strength, quality, and consistency of the evidence. • Make recommendations about applicability of evidence to clinical nursing practice that guides development of a health promotion project about osteoporosis risk reduction for postmenopausal women with osteopenia. How does the literature review differ when it is used for research purposes versus consumer of research purposes? The literature review in a research study is used to develop a sound research proposal for a study that will generate knowledge. From a consumer perspective, the major focus of reviewing the literature is to uncover the best available evidence on a given topic that has been generated by research studies that can potentially be used to improve clinical practice and patient outcomes. From a student perspective, the ability to critically appraise the literature is essential to acquiring a skill set for successfully completing scholarly papers, presentations, debates, and evidence-based practice projects. Both types of literature reviews are similar in that both should be framed in the context of previous research and background information and pertinent to the objectives presented in Box 3-1. In your student role, when you are preparing an academic paper, you read the required course materials, as well as additional literature retrieved from your electronic search on your topic. Students often state, “I know how to do research.” Perhaps you have thought the same thing because you “researched” a topic for a paper in the library. However, in this situation it would be more accurate for you to say that you have “searched” the literature to uncover research and conceptual information to prepare an academic paper on a topic. You will search for primary sources, which are articles, books, or other documents written by the person who conducted the study or developed the theory. You will also search for secondary sources, which are materials written by persons other than the those who conducted a research study or developed a particular theory. Table 3-1 provides definitions and examples of primary and secondary sources, and Table 3-2 shows steps and strategies for conducting a literature search. TABLE 3-2 STEPS AND STRATEGIES FOR CONDUCTING A LITERATURE SEARCH In Chapter 1, the EBM hierarchy of evidence is introduced to help you determine the levels of evidence of sources and the quality, quantity, and consistency of the evidence located during a search. Here, the “6S” hierarchy of pre-appraised evidence (Figure 3-3) is introduced to help you find pre-appraised evidence or evidence that has previously undergone an evaluation process for your clinical questions. This model (DiCenso et al., 2009) was developed to assist clinicians in their search for the highest level of evidence. Therefore, the main use of the 6S hierarchy is for efficiently identifying the highest level of evidence to facilitate your search on your clinical question or problem. It is important to keep in mind that there are limitations to using pre-appraised sources because they might not address your particular clinical question. This model suggests that, when searching the literature, you consider prioritizing your search strategy and begin your search by looking for the highest level information resource available. The next level down is Summaries, which includes clinical practice guidelines and electronic evidence-based textbooks such as Clinical Evidence (www.clinicalevidence.com), Dynamed (http://dynamed.ebscohost.com/), the Physicians Information and Education Resource (PIER) (http://pier.acponline.org/overview.html), and UpToDate (http://www.uptodate.com). These summaries about specific conditions are updated regularly. Also included in Summaries are evidence-based guidelines that provide recommendations based on high quality evidence. Many organizations like the Oncology Nursing Society create evidence-based guidelines called Putting Evidence into Practice (http://www.ons.org/Research/PEP/). The next level, Synopses of Syntheses, provides a pre-appraised summary of a systematic review. These can be found in journals such as Evidence-Based Nursing (http://ebn.bmj.com/) and Evidence-Based Medicine (http://ebm.bmj.com/) or in the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb/AboutDare.asp). These synopses provide a synthesis of the review; some include a commentary related to strength of the evidence and applicability to a patient population. Syntheses (Systematic Reviews) are the next type of information resource in the 6S pyramid. Systematic reviews (e.g., a Cochrane review) are a synthesis of research on a clinical topic. Systematic reviews use strict methods to search and appraise studies. They include quantitative summaries—meta-analysis (see Chapter 11). Studies is the bottom of the pyramid. This level also addresses single studies that have been pre-appraised. Although levels 5 and 6 may appear similar, there are differences. The major difference is that the process for appraising level 5 is conducted by a varied number of experts, depending on the evidence-based abstraction journal’s criteria, and a brief overview and a rating in relation to use in practice is included, whereas a “Synopses of a Single Study” appraisal is conducted by a single expert. For example, in the abstraction journal Nursing+, single studies included on their site “are pre-rated for quality by research staff, then rated for clinical relevance and interest by at least three members of a worldwide panel of practicing nurses” who write a brief overview of the study and provide a rating between 1-7 using the Best Evidence for Nursing+ Rating Scale. A rating of 5 or above is most useful for practice (http://plus.mcmaster.ca/NP/Default.aspx, retrieved July 14, 2012). As with level 5, you must see if your library has institutional licenses for evidence-based abstraction journals such as Journalwise ACP, EvidenceUpdates, or Nursing+ (DiCenso et al., 2009).

Gathering and appraising the literature

Review of the literature

The literature review: The researcher’s perspective

PRIMARY: ESSENTIAL

SECONDARY: USEFUL

Material written by the person who conducted the study, developed the theory (model), or prepared the scholarly discussion on a concept, topic, or issue of interest (i.e., the original author).

Other primary sources include: autobiographies, diaries, films, letters, artifacts, periodicals, Internet communications on e-mail, listservs, interviews (e.g., oral histories, e-mail), photographs and tapes.

Can be published or unpublished.

Primary source example: An investigator’s report of their research study (e.g., articles in Appendices A–D) and the Cochrane report (Appendix E).

Theoretical example: The following statement by Mercer (2004) cited from her original work is an example of a primary source of a theory. Mercer’s conclusion states: “The argument is made to replace ‘maternal role attainment’ with becoming a mother to connote the initial transformation and continuing growth of the mother.” (p. 231)

hint: Critical appraisal of primary sources is essential to a thorough and relevant review of the literature.

Material written by a person(s) other than the person who conducted the research study or developed the theory. This material summarizes or critiques another author’s original work and is usually in the form of a summary or critique (i.e., analysis and synthesis) of another’s scholarly work or body of literature. Mainly used for Theoretical and Conceptual Framework.

Other secondary sources include: response/commentary/critique of a research study, a theory paraphrased by others, or a work written by someone other than the original author (e.g., a biography or clinical article).

Can be published or unpublished.

Secondary source example: An edited textbook (e.g., LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. [2014]. Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice [8th ed.], Philadelphia, Elsevier.)

Theoretical example: Alhusen and colleague’s 2012 description of the theoretical model for their study paraphrases a number of theoretical sources (Cranley, 1981; Rubin, 1967; Mercer, 2004) related to the relationship of the mother to the fetus and the role of mother (see Appendix B).

hint: Use secondary sources sparingly; however, secondary sources, especially a study’s literature review that presents a critique of studies, is a valuable learning tool for a beginning research consumer.

The literature review: The consumer perspective

Research conduct and consumer of research purposes: Differences and similarities

Searching for evidence

STEPS OF LITERATURE REVIEW

STRATEGY

Step I: Determine clinical question or research topic

Keep focused on the types of patients that you care for in your setting. Keep focused on the assignment’s objective; if EBP project start with a PICO question. Use the literature to develop your ideas.

Step II: Identify key variables/terms

Ask your reference librarian for help, and read the online Help. Include the elements of your PICO and see if you can limit to research articles or use publication types to focus your results.

Step III: Conduct computer search using at least two recognized electronic databases

Conduct the search yourself or with the help of your librarian; it is essential to use at least two health-related databases, such as CINAHL via EBSCO, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, or ERIC.

Step IV: Review abstracts online and weed out irrelevant articles

Scan through your retrieved search, read the abstracts provided, and mark only those that fit your topic; select “references” as well as “search history” and “full-text articles” if available, before printing, saving, or e-mailing your search.

Step V: Retrieve relevant sources

Organize by article type or study design and year and reread the abstracts to determine if the articles chosen are relevant and worth retrieving.

Step VI: Store or print relevant articles; if unable to print directly from database order through interlibrary loan

Download the search to an online search management, writing and collaboration tool designed to help you (e.g., RefWorks, EndNote, Zotero). Using a system will ensure that you have the information for each citation (e.g., journal name, year, volume number, pages) and it will format the reference list—this can save an immense amount of time when composing your paper. Download PDF versions of articles as needed.

Step VII: Conduct preliminary reading and weed out irrelevant sources

Review critical reading strategies (e.g., read the abstract at the beginning of the articles [see Chapter 1]).

Step VIII: Critically read each source (summarize and critique each source)

Use critical appraisal strategies (e.g., use an evidence table [see Chapter 19] or a standardized critiquing tool), process each summary and critical appraisal (no more than one page long), include the references in APA style at the top or bottom of each abstract.

Step IX: Synthesize critical summaries of each article

Decide how you will present the synthesis of overall strengths and weaknesses of the reviewed articles (e.g., present chronologically and according to type: research as well as conceptual literature-so the reader can see the evidence’s progression; or present similarities and differences between and among studies and or concepts). At the end summarize the findings of the literature review, draw a conclusion and make recommendations based on your conclusion. Include the reference list.

Gathering and appraising the literature

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access