22 Fundamentals of Patient Safety and Quality Improvement

Pearls

• Following the documentation of patient death and complication rate related to medical errors and preventable complications, it is now clear that an essential component of healthcare delivery is improving the safety and quality of healthcare.

• Healthcare improvement efforts prevent iatrogenic injury and maximize positive patient outcomes by incorporating the psychology of human behavior, evidence-based standards of care, and performance measurement into clinical processes and systems.

• “High-reliability” organizations have low patient morbidity and mortality, a low rate of error and complications, and they continuously learn from the analysis of potential system flaws and actual adverse events. The staff of high reliability organizations raise concerns and make decisions to support safety practices and standardize processes, and there is leadership support for this approach.

• Pediatric critical care is highly vulnerable to errors and adverse patient events, so pediatric critical care nurses must be particularly vigilant in promoting a safe work environment, and compliance with medication safety, prevention of healthcare-acquired infections, and other evidence-based methods to improve patient care outcomes.

Overview of patient safety and healthcare quality improvement

Healthcare professionals practice with the intention of promoting the well-being of their patients. Yet despite the dedication, intelligence, and education of healthcare professionals, encounters often fall short of providing safe and high-quality care. The discipline of healthcare improvement has grown out of mounting evidence that many patients are inadvertently harmed by the care that is intended to make them well and that patient outcomes are denigrated by suboptimal care delivery systems.51,56 Healthcare improvement efforts prevent iatrogenic injury and maximize positive patient outcomes by incorporating the psychology of human behavior, evidence-based standards of care, and performance measurement into clinical processes and systems. Although patient safety and quality improvement programs may be considered the domain of managers and administrators, the ultimate responsibility to deliver safe and high quality care falls squarely on front-line clinicians. Pediatric critical care nurses must understand childhood diseases and their treatment, but also must know when, how, and why their work might fail to meet the needs of patients, and they must have the tools to make care safer and more effective.

Institute of Medicine Reports: The Case for Improving Healthcare Safety and Quality

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System estimated that 100,000 people die every year in the United States as the result of preventable errors made by healthcare professionals.51 The statistics presented in this study ranked medical errors as the eighth leading cause of death and demonstrated that more people die because of medical errors than from motor vehicle crashes, breast cancer, or AIDS.7,18,51 The report attributed 7000 of the deaths to medication errors and estimated the annual cost of errors at $17 billion to $29 billion.51

The To Err is Human report exposed the inadequacies of healthcare systems, focused attention on patient safety, and fostered programs dedicated to measuring and improving performance. Table 22-1 outlines the recommendations for healthcare improvement that were presented in the To Err is Human report and endorsed by the IOM’s Quality of Health Care in America Committee. In a follow-up to the To Err is Human report, in 2001 the IOM published Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, to more fully address quality problems related to patient-family satisfaction, treatment disparities, and resource accessibility.21,64,65 Crossing the Quality Chasm defines the ideal twenty-first century healthcare system as one that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. Table 22-2 defines the six aims set forth by the IOM and highlights the recommendations of the Crossing the Quality Chasm report for achieving the ideal healthcare system.

Table 22-1 The Institute of Medicine Quality of Health Care in America Committee’s Recommendations for Health Care Improvement

| Tier | Goal | Action |

| Leadership and knowledge | Establish national leadership, research, tools, and protocols to enhance patient safety knowledge | Development of a Center for Patient Safety within the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| Identifying and learning from errors | Identify and learn through errors via mandatory and voluntary reporting efforts with an emphasis on using information to make systems safer | Development of reporting standards by the National Forum for Health Care Quality Measurement and Reporting and analysis of the data by the Center for Patient Safety |

| Requirement for state departments of health to report adverse events | ||

| Designation of federal funding for the development of reporting systems | ||

| Creation of legislation to extend peer review protections to data related to patient safety and quality improvement | ||

| Setting performance standards and expectations | Raise the standard and expectations for the improvement of safety through the actions of oversight organizations, professional organizations, and group purchasers | Inclusion of patient safety indicators in performance standards |

| Implementation of patient safety programs by regulators and accreditors, public and private healthcare purchasers and health professional licensing, certifying and credentialing agencies | ||

| Development of patient safety committees within professional societies | ||

| Increased post-marketing monitoring of drugs by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration | ||

| Implementing safety systems in healthcare organizations | Create safe systems within healthcare organizations by implementing safe practices at the delivery level | Incorporation of patient safety programs, with executive sponsorship, into all healthcare institutions |

| Adoption of safe medication practices by all healthcare institutions |

From Kohn KT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS: To err is human: building a safer healthcare system, Washington, DC, 1999, National Academy Press; National Academy of Sciences: To err is human: building a safer healthcare system executive summary. Available at http://www.nap.edu. Accessed October 8, 2011.

Table 22-2 Institute of Medicine Six Aims for Improvement of Health Care Systems

| Aim | Definition | Recommendations for Achieving the Six Quality Aims |

|---|---|---|

| Safe | Avoid injuries to patients from care that was intended to help them. | • Designate federal funding to healthcare quality improvement initiatives. • Reduce illogical variability in treatment between individual clinicians and institutions and promote the use of evidence-based practices. • Increase transparency of information regarding the performance of healthcare institutions. • Allow patients to access to their own medical records and clinical knowledge. • Implement mechanisms for active communication and exchange of information among healthcare providers. • Create an information technology infrastructure that eliminates the need for handwritten documentation of care. • Align payment policies with quality improvement. • Prepare the workforce to understand and implement quality improvement aims. |

| Effective | Provide services that are based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refrain from providing services to those who are not likely to benefit. | |

| Patient-centered | Provide care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values and ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions. | |

| Timely | Reduce wait time and harmful delays for those who both receive and give care. | |

| Efficient | Avoid waste such as wasteful use of supplies, ideas and energy. | |

| Equitable | Provide care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location and socio-economic status. |

From Committee on Quality Health Care in America and Institute of Medicine: Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC, 2001, National Academy Press; National Academy of Sciences: Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century executive summary, 2003. Available at http://www.nap.edu. Accessed October 8, 2011.

Through the implementation of the IOM recommendations and the work of organizations that have evolved to improve the safety and quality of healthcare (see the table in the Chapter 22 Supplement on the Evolve Website for a list of organizations and their focuses and websites), individual institutions have demonstrated incremental improvement in care. As late as 2005, however, national statistics had not improved substantially.2,56 Furthermore, the data compiled in 1999 may have underestimated deficiencies in patient safety.56 For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data subsequent to the To Err is Human report suggest that healthcare-acquired blood stream infections may account for as many as 90,000 deaths every year.19,56 In light of these projections, it is clear that an essential component of contemporary healthcare delivery is improving the safety and quality of healthcare for patients of all ages.

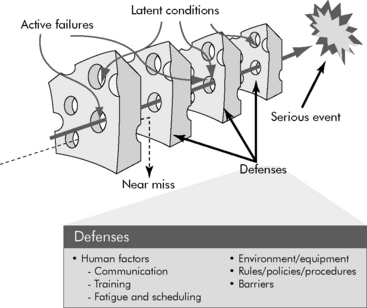

Human Error

Refer to the Chapter 22 Supplement on the Evolve Website for a history of the industry-based theories of human error. Error theorists recommend a systems approach to improving workplace performance. Extrapolated from successful programs in the nuclear power and aviation industries, a systems approach to preventing human error starts with the notion that people are intrinsically fallible. In addition, it encourages error-proofing the systems in which people work. In a systems approach to error-proofing, layers of defensive interventions that respond to failure-prone human behaviors are used to prevent or trap errors before they cause harm. Often referred to as the Swiss Cheese Model (Fig. 22-1), Reason’s system theory79 illustrates that despite layers of defense, it is possible for holes in the safeguards to align in such a way that an error passes through the system. The model proposes that to be maximally effective, multiple defensive layers are necessary to reduce the likelihood that the holes will align and allow the system to fail. In environments such as critical care units, layers of defense are often technologic, such as redundant monitor alarms that sound at the bedside and at a central monitoring station and may also alert staff via a visual cue, such as a flashing light.79

Fig. 22-1 The Swiss Cheese Model of Errors: holes in layers of defense allow errors to pass through a system.

(Adapted from Reason JT: Human error, New York, 1991, Cambridge University Press.)

Reason notes that errors in systems are caused by either “active failures” or “latent conditions.”79 In healthcare, an active failure is an unsafe act performed by a professional who is in direct contact with a patient. A latent condition is a flaw in the design of the care delivery system and its layers of defense. In keeping with the Swiss Cheese Model, patient safety is promoted by barriers to both the active failures of professionals and the latent conditions of a system. Successful error prevention only adds defensive layers and minimizes the number of potential failures that exist in the system. A common approach to prospectively analyzing a system for potential failures is failure mode effect analysis (FMEA). Root cause analysis (RCA) is a technique for assigning a cause to errors that have actually occurred. The methodologies for FMEA and RCA are described later in this chapter. Such preoccupation with errors, their cause, and their prevention is a key characteristic of safe and high reliability industries.79

High Reliability Organizations

Reliability is the rate at which a system produces a desired effect without failure.80 High reliability organizations perform well in hazardous situations that depend on technology and human interactions.114 (Refer to the Chapter 22 Supplement on the Evolve Website for information about the study of nuclear power and aviation accidents.) By understanding the interplay between the technical and human causes of accidents, the nuclear power and aviation industries have significantly improved the safety of their practices and are now considered high reliability organizations. Regardless of the industry, all high reliability organizations share the following characteristics:

Box 22-1 lists the characteristics of high reliability organizations. In addition to a high rate of positive patient outcomes and a low rate of error and complications, evidence of reliability in a healthcare organization includes continual learning from the analysis of potential system flaws and actual adverse events, the ability of staff at any level to raise concerns and make decisions that are within the scope of their expertise, standardization of processes, and leadership support for safety practices.16,60,77

Culture of Safety

The ability of a healthcare system to be highly reliable hinges on its underlying organizational culture and leadership support for a culture of safety. To fully support a culture of safety, leadership must prioritize and build consensus on the importance of safety and quality improvement goals and must remove barriers and conflicts of interest to achieving these goals. Leadership can also promote a culture of safety by using nonpunitive approaches to investigating errors and by promoting transparency for the purpose of learning from adverse events.37,92 Evidence that a culture of safety exists in an organization includes sufficient staff and resources, a flat organizational hierarchy, open dialogue about problems without fear of repercussion, clear lines of communication and effective intradisciplinary and interdisciplinary teamwork.63,72 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality provides a survey that can be used to assess the culture of safety in a hospital3 (Box 22-2).

Box 22-2 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Hospital Survey Questions on Patient Safety Culture

1. Do people support one another in this unit?

2. Do we have sufficient staff to handle the workload?

3. When a lot of work needs to be done quickly, do we work together as a team to get the work done?

4. Do people treat each other with respect?

5. Do staff members in this unit work longer hours than is best for patient care?

6. Are we are actively doing things to improve patient safety?

7. Do we use more agency or temporary staff than is best for patient care?

8. Do staff believe that their mistakes are held against them?

9. Do mistakes lead to positive changes here?

10. Is it just by chance that more serious mistakes don’t happen around here?

11. When one area in this unit gets really busy, do others help out?

12. When an event is reported, does it seem as though the person is being written up, not the problem?

13. After we make changes to improve patient safety, do we evaluate their effectiveness?

14. Do we work in “crisis mode” trying to do too much, too quickly?

15. Is patient safety ever sacrificed to get more work done?

16. Do staff members worry that mistakes they make are kept in their personnel file?

17. Do we have patient safety problems in this unit?

18. Are our procedures and systems good at preventing errors?

19. Does my supervisor or manager say a good word when they see a job done according to established patient safety procedures?

20. Does my supervisor or manager seriously consider staff suggestions for improving patient safety?

21. Whenever pressure builds, does my supervisor or manager wants us to work faster, even if it means taking shortcuts?

22. Does my supervisor or manager overlook patient safety problems that happen repeatedly?

23. Are we are given feedback about changes put into place based on event reports?

24. Will staff members freely speak up if they see something that may negatively affect patient care?

25. Are we are informed about errors that happen in this unit?

26. Do staff members feel free to question the decisions or actions of those with more authority?

27. Do staff members discuss ways to prevent errors from happening again?

28. Are staff members afraid to ask questions when something does not seem right?

29. When a mistake is made, but is caught and corrected before affecting the patient, how often is this reported?

30. When a mistake is made, but has no potential to harm the patient, how often is this reported?

31. When a mistake is made that could harm the patient, but does not, how often is this reported?

32. Does hospital management provide a work climate that promotes patient safety?

33. Do hospital units coordinate well with each other?

34. Do things “fall between the cracks” when transferring patients from one unit to another?

35. Is there good cooperation among hospital units that need to work together?

36. Is important patient care information often lost during shift changes?

37. Is it often unpleasant to work with staff members from other hospital units?

38. Do problems often occur in the exchange of information across hospital units?

39. Do the actions of hospital management show that patient safety is a top priority?

40. Does hospital management seem interested in patient safety only after an adverse event happens?

41. Do hospital units work well together to provide the best care for patients?

42. Are shift changes problematic for patients in this hospital?

Adapted from Patient Safety culture surveys, Rockville, MD, 2009, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/patientsafetyculture/. Accessed October 1, 2009.

Crew Resource Management

Effective teamwork and communication are key features of the safety culture in high reliability organizations. Initially developed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Aerospace Human Factors Research Division to train flight crews, crew resource management (CRM), is essential for the effective functioning of multidisciplinary healthcare teams (Box 22-3). CRM includes team training via simulations and interactive group briefings that focus on the development of behaviors critical to decision making and performance in high-risk and high-stress environments that depend on technology, process, and interpersonal communication.72 The ultimate goal of CRM is a “shared mental model” that aligns all team members to the goals and the strategies for any team activity.96 Behaviors taught to team members via CRM include:

Box 22-3 Crew Resource Management: Core Components of Teamwork Training

In addition to teaching these core behaviors, CRM provides team members with the opportunity to develop technical proficiency and to practice avoiding and trapping errors and mitigating their consequences, and it helps participants appreciate the effects of stress, fatigue, and work overload on performance. Serial performance appraisal of team members is also an important component of CRM programs.72,96

Healthcare team training programs have gained acceptance over the past 10 years, and performance of labor and delivery, surgical, and anesthesia teams have demonstrated the positive effects of CRM.30,59,69 The Joint Commission concluded that communication failures contribute to more than half of all errors.40 In response, the Joint Commission and other patient safety interest groups have mandated the use of the structured inquiries and briefings that are central to CRM. Examples of such mandated CRM methods include the performance of “universal protocol” or “time-out” to confirm the correct patient, procedure, and site before invasive interventions, and the use of standardized templates or scripts for hand-off communication between caregivers.12,40,41,70,84,95

An appreciation for the importance of CRM has also expanded the use of simulation in healthcare. In critical care settings, the tradition of simulating resuscitations has taken new direction and is now used to teach delegation and communication skills and to reinforce clinical decision-making algorithms and procedural techniques.29,69 Simulation, which was once a tool reserved for advanced life support and crisis resource management training (such as learning to manage a difficult airway), can be used to develop virtually any aspect of critical care team performance, including noncrisis activities such as daily rounds.40,69

Healthcare improvement methodology

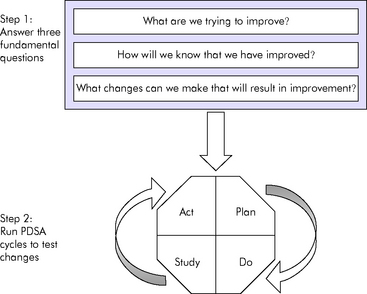

Model for Improvement

Theories of quality improvement and human error provide a foundation for programs in patient safety and quality improvement, but healthcare teams also need practical methods for orchestrating improvement initiatives. Developed by Associates in Process Improvement, the Model for Improvement (Fig. 22-2) is widely considered an appropriate quality improvement method for healthcare.104 The Model for Improvement is a two-step process consisting of (1) answering questions to define the improvement opportunity and (2) conducting plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles to test interventions that are hoped to improve performance.24,44,54,104

Fig. 22-2 The model for improvement.

(Adapted from Institute for Healthcare Improvement: How to improve. Available at http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove. Accessed April 25, 2008; Langley GJ, et al: The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance, San Francisco, 1996, Jossey-Bass.)

• Sponsors and champions: support and remove barriers to improvement and promote a culture of safety; they are often members of upper management or executive administrators

• Leaders: manage the team and the project and organize the work

• Members: determine the course or action and perform improvement actions or changes; they are subject matter experts

• Facilitators: help the team work together effectively; they are external to the issue

When the initiative includes direct patient care or operations that support patient care, the team consists of members of the clinical microsystem. The clinical microsystem is the group of people who work together on a regular basis to provide care to a discrete population of patients. Members of the clinical microsystem are best able to provide subject matter expertise and encourage the adoption of change throughout an organization.68

• Planning the improvement action, including the measures and data collection process

• Doing or performing the improvement action, as a test or small scale trial, and collecting performance data

• Studying the outcome of the test and using the data to uncover what did and did not work

• Acting on the information learned from the test to plan next steps

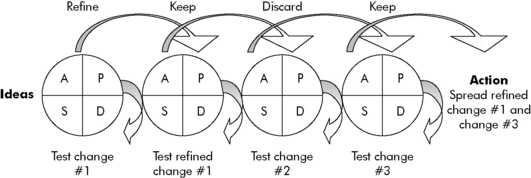

When an improvement effort requires multiple improvement interventions, each intervention can be tested via a separate PDSA cycle. All the related PDSA cycles are then linked to create a package of interventions that have been proven to foster improvement (Fig. 22-3). Effective improvement actions can then be spread beyond the initial test setting and population. The use of PDSA cycles to test and refine improvement actions can help to overcome an organization’s natural resistance to change.24,44,54,105

Fig. 22-3 Linking plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles: moving ideas to action.

(Adapted from Institute for Healthcare Improvement: How to improve. Available at http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove. Accessed April 25, 2008; Langley GJ, et al: The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance, San Francisco, 1996, Jossey-Bass.)

Performance Measurement

• Outcome measures: measure the end result, overall performance, or outcome of an improvement effort

• Process measures: measure the rate of use and performance of a process within a comprehensive improvement effort

• Balancing measures: measure the consequences of the planned changes associated with the improvement effort44,54,104

• The outcome measure is the rate of infection.

• The process measures are the rates of use of recommended practices, such as rate of compliance with conducting and documenting a daily review for continued line necessity. An additional related process measure may also be the time to remove central lines.

• Assuming that the peripheral venous access would be used more often if central lines are removed quickly as a result of daily line necessity reviews, an appropriate balancing measure for the project is the rate of peripheral line complications, such as infiltration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at