Distinguish research utilization and evidence-based practice (EBP) and discuss their current status within nursing

Identify several resources available to facilitate EBP in nursing practice

Identify several resources available to facilitate EBP in nursing practice

List several models for implementing EBP

List several models for implementing EBP

Discuss the five major steps in undertaking an EBP effort for individual nurses

Discuss the five major steps in undertaking an EBP effort for individual nurses

Identify the components of a well-worded clinical question and be able to frame such a question

Identify the components of a well-worded clinical question and be able to frame such a question

Discuss broad strategies for undertaking an EBP project at the organizational level

Discuss broad strategies for undertaking an EBP project at the organizational level

Distinguish EBP and quality improvement (QI) efforts

Distinguish EBP and quality improvement (QI) efforts

Define new terms in the chapter

Define new terms in the chapter

Key Terms

Clinical practice guideline

Clinical practice guideline

Cochrane Collaboration

Cochrane Collaboration

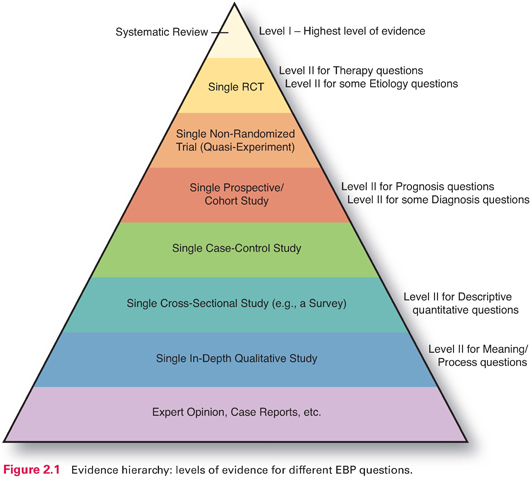

Evidence hierarchy

Evidence hierarchy

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice

Implementation potential

Implementation potential

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis

Metasynthesis

Metasynthesis

Pilot test

Pilot test

Quality improvement (QI)

Quality improvement (QI)

Research utilization (RU)

Research utilization (RU)

Systematic review

Systematic review

Learning about research methods provides a foundation for evidence-based practice (EBP) in nursing. This book will help you to develop methodologic skills for reading research articles and evaluating research evidence. Before we elaborate on methodologic techniques, we discuss key aspects of EBP to further help you understand the key role that research now plays in nursing.

BACKGROUND OF EVIDENCE-BASED NURSING PRACTICE

This section provides a context for understanding evidence-based nursing practice and two closely related concepts: research utilization and knowledge translation.

Definition of Evidence-Based Practice

Pioneer Sackett and his colleagues (2000) defined evidence-based practice as “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values” (p. 1). The definition proposed by Sigma Theta Tau International (2008) is as follows: “The process of shared decision-making between practitioner, patient, and others significant to them based on research evidence, the patient’s experiences and preferences, clinical expertise or know-how, and other available robust sources of information” (p. 57). A key ingredient in EBP is the effort to personalize “best evidence” to a specific patient’s needs within a particular clinical context.

A basic feature of EBP as a clinical problem-solving strategy is that it de-emphasizes decisions based on custom, authority, or ritual. A core aspect of EBP is on identifying the best available research evidence and integrating it with other factors in making clinical decisions. Advocates of EBP do not minimize the importance of clinical expertise. Rather, they argue that evidence-based decision making should integrate best research evidence with clinical expertise, patient preferences, and local circumstances. EBP involves efforts to personalize evidence to fit a specific patient’s needs and a particular clinical situation.

Because research evidence can provide valuable insights about human health and illness, nurses must be lifelong learners who have the skills to search for, understand, and evaluate new information about patient care and the capacity to adapt to change.

Research Utilization

Research utilization (RU) is the use of findings from studies in a practical application that is unrelated to the original research. In RU, the emphasis is on translating new knowledge into real-world applications. EBP is a broader concept than RU because it integrates research findings with other factors, as just noted. Also, whereas RU begins with the research itself (e.g., How can I put this new knowledge to good use in my clinical setting?), the starting point in EBP is usually a clinical question (e.g., What does the evidence say is the best approach to solving this clinical problem?).

During the 1980s, RU emerged as an important topic. In education, nursing schools began to include courses on research methods so that students would become skillful research consumers. In research, there was a shift in focus toward clinical nursing problems. Yet, concerns about the limited use of research evidence in the delivery of nursing care continued to mount.

The need to reduce the gap between research and practice led to formal RU projects, including the groundbreaking Conduct and Utilization of Research in Nursing (CURN) Project, a 5-year project undertaken by the Michigan Nurses Association in the 1970s. CURN’s objectives were to increase the use of research findings in nurses’ daily practice by disseminating current findings and facilitating organizational changes needed to implement innovations (Horsley et al., 1978). The CURN Project team concluded that RU by practicing nurses was feasible but only if the research is relevant to practice and if the results are broadly disseminated.

During the 1980s and 1990s, RU projects were undertaken by numerous hospitals and organizations. During the 1990s, however, the call for RU began to be superseded by the push for EBP.

The Evidence-Based Practice Movement

One keystone of the EBP movement is the Cochrane Collaboration, which was founded in the United Kingdom based on the work by British epidemiologist Archie Cochrane. Cochrane published a book in the 1970s that drew attention to the shortage of solid evidence about the effects of health care. He called for efforts to make research summaries about interventions available to health care providers. This led to the development of the Cochrane Center in Oxford in 1993 and the international Cochrane Collaboration, with centers now established in locations throughout the world. Its aim is to help providers make good decisions by preparing and disseminating systematic reviews of the effects of health care interventions.

At about the same time that the Cochrane Collaboration was started, a group from McMaster Medical School in Canada developed a learning strategy they called evidence-based medicine. The evidence-based medicine movement, pioneered by Dr. David Sackett, has broadened to the use of best evidence by all health care practitioners. EBP has been considered a major paradigm shift in health care education and practice. With EBP, skillful clinicians can no longer rely on a repository of memorized information but rather must be adept in accessing, evaluating, and using new research evidence.

The EBP movement has advocates and critics. Supporters argue that EBP is a rational approach to providing the best possible care with the most cost-effective use of resources. Advocates also note that EBP provides a framework for self-directed lifelong learning that is essential in an era of rapid clinical advances and the information explosion. Critics worry that the advantages of EBP are exaggerated and that individual clinical judgments and patient inputs are being devalued. They are also concerned that insufficient attention is being paid to the role of qualitative research. Although there is a need for close scrutiny of how the EBP journey unfolds, an EBP path is the one that health care professions will almost surely follow in the years ahead.

| TIP A debate has emerged concerning whether the term evidence-based practice should be replaced with evidence-informed practice (EIP). Those who advocate for a different term have argued that the word “based” suggests a stance in which patient values and preferences are not sufficiently considered in EBP clinical decisions (e.g., Glasziou, 2005). Yet, as noted by Melnyk (2014), all current models of EBP incorporate clinicians’ expertise and patients’ preferences. She argued that “changing terms now . . . will only create confusion at a critical time where progress is being made in accelerating EBP” (p. 348). We concur and we use EBP throughout this book. |

Knowledge Translation

RU and EBP involve activities that can be undertaken at the level of individual nurses or at a higher organizational level (e.g., by nurse administrators), as we describe later in this chapter. A related movement emerged that mainly concerns system-level efforts to bridge the gap between knowledge generation and use. Knowledge translation (KT) is a term that is often associated with efforts to enhance systematic change in clinical practice. The World Health Organization (WHO) (2005) has defined KT as “the synthesis, exchange, and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders to accelerate the benefits of global and local innovation in strengthening health systems and improving people’s health.”

| TIP Translation science (or implementation science) is a new discipline devoted to promoting KT. In nursing, the need for translational research was an important stimulus for the development of the Doctor of Nursing Practice degree. Several journals have emerged that are devoted to this field (e.g., the journal Implementation Science). |

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE IN NURSING

Before describing procedures relating to EBP in nursing, we briefly discuss some important issues, including the nature of “evidence,” challenges to pursuing EBP, and resources available to address some of those challenges.

Types of Evidence and Evidence Hierarchies

There is no consensus about what constitutes usable evidence for EBP, but there is general agreement that findings from rigorous research are paramount. Yet, there is some debate about what constitutes “rigorous” research and what qualifies as “best” evidence.

Early in the EBP movement, there was a strong bias favoring evidence from a type of study called a randomized controlled trial (RCT). This bias reflected the Cochrane Collaboration’s initial focus on evidence about the effectiveness of therapies rather than about broader health care questions. RCTs are especially well-suited for drawing conclusions about the effects of health care interventions (see Chapter 9). The bias in ranking research approaches in terms of questions about effective therapies led to some resistance to EBP by nurses who felt that evidence from qualitative and non-RCT studies would be ignored.

Positions about the contribution of various types of evidence are less rigid than previously. Nevertheless, many published evidence hierarchies rank evidence sources according to the strength of the evidence they provide, and in most cases, RCTs are near the top of these hierarchies. We offer a modified evidence hierarchy that looks similar to others but is unique in illustrating that the ranking of evidence-producing strategies depends on the type of question being asked.

Figure 2.1 shows that systematic reviews are at the pinnacle of the hierarchy (Level I) because the strongest evidence comes from careful syntheses of multiple studies. The next highest level (Level II) depends on the nature of inquiry. For Therapy questions regarding the efficacy of a therapy or intervention (What works best for improving health outcomes?), individual RCTs constitute Level II evidence (systematic reviews of multiple RCTs are Level I). Going down the “rungs” of the evidence hierarchy for Therapy questions results in less reliable evidence. For example, Level III evidence comes from a type of study called quasi-experimental. In-depth qualitative studies are near the bottom, in terms of evidence regarding intervention effectiveness. (Terms in Fig. 2.1 will be discussed in later chapters.)

For a Prognosis question, by contrast, Level II evidence comes from a single prospective cohort study, and Level III evidence is from a type of study called case-control (Level I evidence is from a systematic review of cohort studies). Thus, contrary to what is often implied in discussions of evidence hierarchies, there really are multiple hierarchies. If one is interested in best evidence for questions about meaning, an RCT would be a poor source of evidence, for example. Figure 2.1 illustrates these multiple hierarchies, with information on the right indicating the type of individual study that would offer the best evidence (Level II) for different questions. In all cases, appropriate systematic reviews are at the pinnacle.

Of course, within any level in an evidence hierarchy, evidence quality can vary considerably. For example, an individual RCT could be well designed, yielding strong Level II evidence for Therapy questions, or it could be so flawed that the evidence would be weak.

Thus, in nursing, best evidence refers to research findings that are methodologically appropriate, rigorous, and clinically relevant for answering pressing questions. These questions cover not only the efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness of nursing interventions but also the reliability of nursing assessment tests, the causes and consequences of health problems, and the meaning and nature of patients’ experiences. Confidence in the evidence is enhanced when the research methods are compelling, when there have been multiple confirmatory studies, and when the evidence has been carefully evaluated and synthesized.

Evidence-Based Practice Challenges

Studies that have explored barriers to evidence-based nursing have yielded similar results in many countries. Most barriers fall into one of three categories: (1) quality and nature of the research, (2) characteristics of nurses, and (3) organizational factors.

With regard to the research itself, one problem is the limited availability of strong research evidence for some practice areas. The need for research that directly addresses pressing clinical problems and for replicating studies in a range of settings remains a challenge. Also, nurse researchers need to improve their ability to communicate evidence to practicing nurses. In non-English-speaking countries, another impediment is that most studies are reported in English.

Nurses’ attitudes and education are also potential barriers to EBP. Studies have found that some nurses do not value or understand research, and others simply resist change. And, among the nurses who do appreciate research, many do not have the skills for accessing research evidence or for evaluating it for possible use in clinical decision making.

Finally, many challenges to using research in practice are organizational. “Unit culture” can undermine research use, and administrative or organizational barriers also play a major role. Although many organizations support the idea of EBP in theory, they do not always provide the necessary supports in terms of staff release time and provision of resources. Strong leadership in health care organizations is essential to making EBP happen.

RESOURCES FOR EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

In this section, we describe some of the resources that are available to support evidence-based nursing practice and to address some of the challenges.

Research evidence comes in various forms, the most basic of which is from individual studies. Primary studies published in journals are not pre-appraised for quality and use in practice.

Preprocessed (pre-appraised) evidence is evidence that has been selected from primary studies and evaluated for use by clinicians. DiCenso and colleagues (2005) have described a hierarchy of preprocessed evidence. On the first rung above primary studies are synopses of single studies, followed by systematic reviews, and then synopses of systematic reviews. Clinical practice guidelines are at the top of the hierarchy. At each successive step in the hierarchy, there is greater ease in applying the evidence to clinical practice. We describe several types of pre-appraised evidence sources in this section.

Systematic Reviews

EBP relies on meticulous integration of all key evidence on a topic so that well-grounded conclusions can be drawn about EBP questions. A systematic review is not just a literature review. A systematic review is in itself a methodical, scholarly inquiry that follows many of the same steps as those for other studies.

Systematic reviews can take various forms. One form is a narrative (qualitative) integration that merges and synthesizes findings, much like a rigorous literature review. For integrating evidence from quantitative studies, narrative reviews increasingly are being replaced by a type of systematic review known as a meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is a technique for integrating quantitative research findings statistically. In essence, meta-analysis treats the findings from a study as one piece of information. The findings from multiple studies on the same topic are combined and then all of the information is analyzed statistically in a manner similar to that in a usual study. Thus, instead of study participants being the unit of analysis (the most basic entity on which the analysis focuses), individual studies are the unit of analysis in a meta-analysis. Meta-analysis provides an objective method of integrating a body of findings and of observing patterns that might not have been detected.

Example of a meta-analysis

Shah and colleagues (2016) conducted a meta-analysis of the evidence on the effect of bathing intensive care unit (ICU) patients with 2% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) on central line–associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI). Integrating results from four intervention studies, the researchers concluded that 2% CHG is effective in reducing infections. They noted that “nursing provides significant influence for the prevention of CLABSIs in critical care via evidence-based best practices” (p. 42).

For qualitative studies, integration may take the form of a metasynthesis. A metasynthesis, however, is distinct from a quantitative meta-analysis: A metasynthesis is less about reducing information and more about interpreting it.

Example of a metasynthesis

Magid and colleagues (2016) undertook a metasynthesis of studies exploring the perceptions of key elements of caregiving among patients using a left ventricular assist device. Their metasynthesis of eight qualitative studies resulted in the identification of eight important themes.

Systematic reviews are increasingly available. Such reviews are published in professional journals that can be accessed using standard literature search procedures (see Chapter 7) and are also available in databases that are dedicated to such reviews. In particular, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) contains thousands of systematic reviews relating to health care interventions.

| TIP Websites with useful content relating to EBP, including ones for locating systematic reviews, are in the Internet Resources for Chapter 2 on |

Clinical Practice Guidelines and Care Bundles

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines distill a body of evidence into a usable form. Unlike systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines (which often are based on systematic reviews) give specific recommendations for evidence-based decision making. Guideline development typically involves the consensus of a group of researchers, experts, and clinicians. The implementation or adaptation of a clinical practice guideline is often an ideal focus for an organizational EBP project.

Also, organizations are developing and adopting care bundles—a concept developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement—that encompass a set of interventions to treat or prevent a specific cluster of symptoms (www.ihi.org). There is growing evidence that a combination or bundle of strategies produces better outcomes than a single intervention.

Example of a care bundle project

Tayyib et al. (2015) studied the effectiveness of a pressure ulcer prevention care bundle in reducing the incidence of pressure ulcers in critically ill patients. Patients who received the bundled interventions had a significantly lower incidence of pressure ulcers than patients who did not.

Finding care bundles and clinical practice guidelines can be challenging because there is no single guideline repository. A standard search in a bibliographic database such as MEDLINE (see Chapter 7) will yield many references; however, the results are likely to include not only the actual guidelines but also commentaries, implementation studies, and so on.

A recommended approach is to search in guideline databases or through specialty organizations that have sponsored guideline development. A few of the many possible sources deserve mention. In the United States, nursing and health care guidelines are maintained by the National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov). In Canada, the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) (www.rnao.org/bestpractices) maintains information about clinical practice guidelines. Two sources in the United Kingdom are the Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP) database and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

There are many topics for which practice guidelines have not yet been developed, but the opposite problem is also true: Sometimes there are multiple guidelines on the same topic. Worse yet, because of differences in the rigor of guideline development and interpretation of evidence, different guidelines sometimes offer different or even conflicting recommendations (Lewis, 2001). Thus, those who wish to adopt clinical practice guidelines should appraise them to identify ones that are based on the strongest evidence, have been meticulously developed, are user-friendly, and are appropriate for local use or adaptation.

Several appraisal instruments are available to evaluate clinical practice guidelines. One with broad support is the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument, now in its second version (Brouwers et al., 2010). The AGREE II instrument has ratings for 23 dimensions within six domains (e.g., scope and purpose, rigor of development, presentation). As examples, a dimension in the scope and purpose domain is “The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described,” and one in the rigor of development domain is “The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication.” The AGREE tool should be applied to a guideline by a team of two to four appraisers.

Example of using AGREE II

Homer and colleagues (2014) evaluated English-language guidelines on the screening and management of group B Streptococcus (GBS) colonization in pregnant women and the prevention of early-onset GBS disease in newborns. Four guidelines were appraised using the AGREE II instrument.

| TIP For those interested in learning more about the AGREE II instrument, we offer more information in the chapter supplement on |

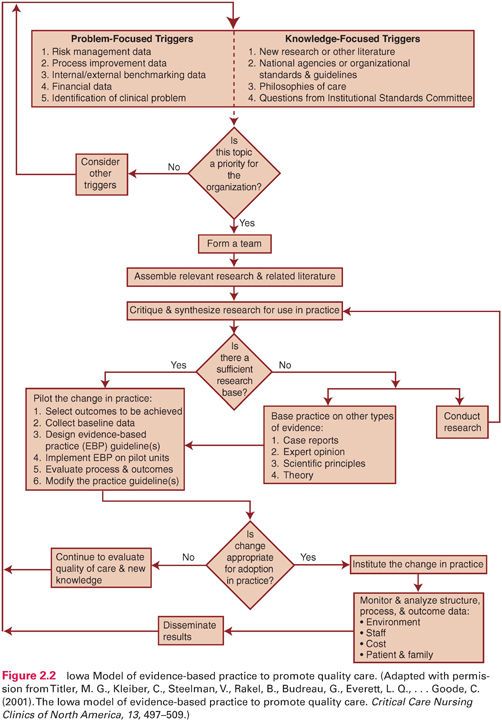

Models of the Evidence-Based Practice Process

EBP models offer frameworks for designing and implementing EBP projects in practice settings. Some models focus on the use of research by individual clinicians (e.g., the Stetler Model, one of the oldest models that originated as an RU model), but most focus on institutional EBP efforts (e.g., the Iowa Model). The many worthy EBP models are too numerous to list comprehensively but include the following:

Advancing Research and Clinical Practice Through Close Collaboration (ARCC) Model (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2015)

Advancing Research and Clinical Practice Through Close Collaboration (ARCC) Model (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2015)

Diffusion of Innovations Model (Rogers, 1995)

Diffusion of Innovations Model (Rogers, 1995)

Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care (Titler, 2010)

Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care (Titler, 2010)

Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model (Dearholt & Dang, 2012)

Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model (Dearholt & Dang, 2012)

Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) Model, (Rycroft-Malone, 2010; Rycroft-Malone et al., 2013)

Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) Model, (Rycroft-Malone, 2010; Rycroft-Malone et al., 2013)

Stetler Model of Research Utilization (Stetler, 2010)

Stetler Model of Research Utilization (Stetler, 2010)

For those wishing to follow a formal EBP model, the cited references should be consulted. Several are also nicely synthesized by Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2015). Each model offers different perspectives on how to translate research findings into practice, but several steps and procedures are similar across the models. We provide an overview of key activities and processes in EBP efforts, based on a distillation of common elements from the various models, in a subsequent section of this chapter. We rely heavily on the Iowa Model, shown in Figure 2.2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree