Chapter 10. Fundamentals of communication

Chapter Contents

Exploring relationships with clients134

Self-esteem, self-confidence and communication135

Listening136

Enabling people to talk137

Asking questions and getting feedback138

Communication barriers140

Overcoming language barriers141

Nonverbal communication141

Written communication145

Summary

This chapter starts with an exploration of client/professional relationships and a discussion of the links between self-esteem, self-confidence and communication, accompanied by a case study on relationship skills. Discussion on four basic communication skills (listening, helping people to talk, asking questions and getting feedback) is followed by consideration of communication and language barriers and nonverbal communication. The chapter ends with a section on written communication. Exercises are provided on overcoming communication barriers and on each basic communication skill.

See also Chapter 12, which discusses communication and education between health promoters and patients.

Effective communication in a range of contexts is fundamental to success in health promotion (See Corcoran 2007 for details on communicating for health promotion in different contexts). Communication should be clear, unambiguous and without distortion of the message.

This chapter discusses some fundamentals of relationships with clients, communication barriers and basic communication skills (see Hartley 2004 for an interesting assessment of possible verbal and nonverbal communication barriers). These skills will often be applied in one-to-one situations, though they may apply when working with groups, running workshops, as well as in more formal situations.

Exploring Relationships with Clients

Health promoters should ask themselves some fundamental (and possibly uncomfortable) questions. For example, what is your basic attitude towards the people to whom your health promotion is directed? Do you accept them on their own terms or do you judge them by your own standards? Do you aim to enable people to be independent, make their own decisions, take control of their health and solve their own health problems? Or are you actually encouraging dependency, solving their problems for them and thereby decreasing their own ability and confidence to take responsibility for their health? It may be useful to work through the following questions, thinking about how you relate to your clients.

Accepting or Judging?

Accepting people is demonstrated by:

• Recognising that clients knowledge and beliefs emerge from their life experience, whereas your own have been modified and extended by professional education and experience.

• Understanding your own knowledge, beliefs, values and standards.

• Understanding your clients’ knowledge, beliefs, values and standards from their point of view.

• Recognising that you and your clients may differ in your knowledge, beliefs, values and standards.

• Recognising that these differences do not suggest that you, the professional health promoter, are a person of greater worth than your clients.

Judging people is demonstrated by:

• Equating people’s intrinsic worth with their knowledge, beliefs, values, standards and behaviour. For example, saying that someone who drinks beyond safe limits is foolish both judges and condemns that person, and takes no account of life experience and cultural background. Saying that drinking beyond safe levels may damage health does not judge the person in the same way.

• Ranking knowledge and behaviour. For example, ‘I’m the expert so I know better than you’ is judgemental; ‘I know a considerable amount about this particular health issue’ is a statement of fact. ‘My standards are higher than yours’ is judgemental; ‘My standards are different from yours’ is not.

Autonomy or Dependency?

There are a number of ways in which you can help clients to take more control over their health.

Autonomy can be enabled by:

• Encouraging people to think things through and make their own health decisions, resisting the urge to dominate the decision-making process.

• Respecting any unusual ideas they may have.

Autonomy can be hindered if:

• You impose your own solution on your clients’ health problems.

• You tell them what to do because they are taking too long to think it through for themselves.

• You tell them that their ideas are not good and won’t work, without giving an adequate explanation or an opportunity to try them out.

An aim which is compatible with health promotion principles and ethical practice is to work towards as much autonomy as possible. By doing this, you are helping people to increase control over their own health. Obviously, there are times when working towards autonomy may not be feasible. For example, it is more demanding of resources and clients may be dependent on a health promoter because they are ill, or uninformed or likely to put themselves or other people in danger.

A Partnership or a One-Way Process?

Do you think of yourself as working in partnership with people in pursuit of health promotion aims, or do you see health promotion as your sole responsibility, with yourself as the expert?

A partnership means:

• There is an atmosphere of trust and openness between yourself and your clients, so that they are not intimidated.

• You ask people for their views and opinions, which you accept and respect even if you disagree with them.

• You tell people when you learn something from them.

• You use informal, participative methods when you are involved in health promotion, drawing on the experience and knowledge that clients bring with them.

• You encourage clients to share their knowledge and experience with each other. People do this all the time, of course (for example, knowledge and experience are discussed between participants on a smoking cessation programme and parents in a baby clinic), but do you actively foster and encourage this?

A one-way process means:

• You do not encourage clients to ask questions and discuss health needs.

• You imply that you do not expect to learn anything from your clients (and if you do learn, you don’t say so).

• You do not find out people’s health knowledge and experience.

• You do not encourage people to learn from each other.

• You use formal health promotion approaches rather than participative methods.

Clients’ Feelings – Positive or Negative?

A change in people’s health knowledge, attitudes and actions will be helped if they feel good about themselves. It will rarely be helped if they are full of self-doubt, anxiety or guilt.

Clients will feel better about themselves if:

• You praise their progress, achievements, strengths and efforts, however small.

• The consequences of unhealthy behaviour such as smoking are discussed without implying that the behaviour is morally bad.

• Time is spent exploring how to overcome difficulties, such as practical strategies to help a client stop smoking. This will help to minimise feelings of helplessness.

Clients will feel bad about themselves if:

• You ignore their strengths and concentrate on their weaknesses.

• You ignore or belittle their efforts.

• You attempt to motivate them by raising guilt and anxiety (such as ‘if you don’t stop smoking you’ll damage your baby’).

To sum up, the health promotion aim of enabling people to take control over and improve their health is best achieved by unconditional positive regard and working in nonjudgemental partnerships (Freshwater 2003). This should seek to build on people’s existing knowledge and experience, move them towards autonomy, empower them to take responsibility for their health and help them to feel positive about themselves.

Self-Esteem, Self-Confidence and Communication

The ability to communicate is closely linked to how people feel about themselves. People with a low sense of self-esteem tend to be over-critical of themselves and to underestimate their abilities (Allen et al 2002). This lack of self-confidence is reflected in their ability to communicate. For example, they may lack assertiveness and thus may either fail to speak up for themselves or react with inappropriate anger and even violence.

Assertiveness means saying what you think and asking for what you want openly, clearly and honestly. It does not mean being aggressive or bullying, but it is in contrast with hiding what you really feel, saying what you don’t really mean or trying to manipulate people into doing what you want.

Assertiveness helps people to create win–win situations (situations where everyone involved feels that they have achieved a reasonable outcome) through direct and open communication and through avoiding aggressive behaviour (which can result in win–lose situations, where one party feels that they have won and the other party feels they have lost) or manipulation (lose–lose situations, where, for example, one party in a negotiation walks out). It builds the self-esteem of all concerned. Successful negotiation is a good example of how assertiveness can work. In a successful negotiation both parties are more likely to come away with the following thoughts:

• This is an agreement which, while not ideal, is good enough for both of us to support.

• Both of us made some compromises and sacrifices.

• We will be able to have successful negotiations with each other in future.

Many clients with low self-esteem will need to learn how to feel better about themselves before they can communicate effectively with health promoters (Emler 2001). Although Emler (2001) reports that most programmes to raise self-esteem had not been successful, people with low self-esteem require key life skills in order to take control of their health. These skills include how to communicate and relate to others in a morally responsible manner, and with respect and sensitivity towards the needs and views of others. Unfortunately, the nonstatutory status and the time allotted to personal and social education in schools may be insufficient for young people to develop these skills (King 2005).

Case study 10.1 illustrates how parents can learn to develop the self-esteem of their children and ensure that their children understand the rights of other people. While the case study refers to parents and children, the same principles can be used by health promoters with their clients.

CASE STUDY 10.1

RELATING SKILLS – LORRAINE AND JACK

Lorraine is late for work and tries to coax her 3-year-old son, Jack, into his coat so that she can take him to nursery school. Jack starts to cry. Lorraine hugs him but tells him that he’s got to go to school. She is at a loss about what else to do, and when she reaches nursery school Jack is still crying. One of the nursery nurses notices his distress and manages to calm him. When Jack has recovered, the nurse talks to Lorraine about what she’s learnt from a book by Gottman & Declaire (1997) and about five steps to better parenting. Lorraine learns that children whose parents consistently practise these five steps have better physical health and score higher academically than children whose parents do not. They also relate better with friends, have fewer behaviour problems and are less prone to acts of violence.

A week later in a similar situation Lorraine tries out what the nurse suggested. She starts in the same way as before, by empathising with Jack, but this time she goes further and provides him with guidance on what to do with his uncomfortable feelings. The conversation goes something like this:

Jack: ‘It’s not fair. I don’t want to go to school’. (Starts to cry.)

Lorraine: ‘Come here Jack’. (Takes him on her knee.) ‘I’m sorry but we can’t stay at home. I have lots to do at work. Does that make you feel sad?’

Jack: (nodding) ‘Yes’.

Lorraine: ‘I feel a bit sad too. It’s OK for you to cry.’ (Hugs him while he cries.) ‘I know what. Let’s think about what to do on Saturday when I don’t have to go to work and you don’t have to go to school. Can you think of anything special you would like to do on Saturday?’

Jack: ‘Can we go to the park and feed the ducks?’

Lorraine: ‘Yes. That would be great.’

Jack: ‘Can Nick come too?’

Lorraine: ‘Perhaps. We’ll have to ask his Mum. But right now it’s time to get going.’

Jack: ‘OK.’

Lorraine has gone through five steps:

1. She becomes aware of Jack’s feelings.

2. She recognises the opportunity for helping Jack to learn about how to handle emotions.

3. She listens to Jack, tries to understand his feelings and lets him know it is OK to feel bad and upset sometimes, and that she has these feelings too.

4. She helps Jack to find the words to label the emotion he is having.

5. She sets limits while exploring strategies to solve the problem.

So, when working with clients with low self-esteem, you may find it helpful to:

• Be aware of the client’s feelings.

• Recognise the opportunity to help the client to learn about how to handle difficult feelings.

• Listen and acknowledge that you have these feelings too.

• Label the feelings.

• Set limits for the interaction while exploring strategies to solve the problem.

Listening

As a health promoter, you need to develop skills of effective listening so that you can help people to talk and identify their needs and feelings.

Listening is an active process. It is not the same as merely hearing words. It involves a conscious effort to listen to words, to the way they are said, to be aware of the feelings shown and of attempts to hide feelings. It means taking note of the nonverbal communication as well as the spoken words. The listener needs to concentrate on giving the speaker full attention, being on the same level physically as the speaker and adopting a nonthreatening posture.

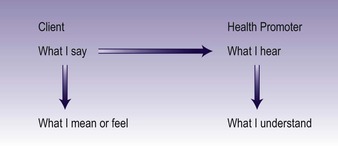

Fig. 10.1 illustrates that active listening involves searching for an understanding of the underlying meaning behind the words used by the client. It shows how the meaning conveyed by the client can become distorted if the client cannot express exactly what he or she means. At the second step it shows that the health promoter may not hear what is being said. Third, the health promoter may hear the words accurately, but interpret them in a different way from that which the client intended.

|

| Fig. 10.1 The listening process. (Figure adapted fromRollnick et al 1999). |

When listening, it is easy to allow attention to wander. Some of the things you may find yourself doing instead of listening are planning what to say next, thinking about a similar experience, interrupting, agreeing or disagreeing, judging, blaming or criticising, interpreting what the speaker says, thinking about the next job to be done or just plain daydreaming.

The task of a listener is to encourage people to talk about their situation unhurriedly and without interruption, enabling them to express their feelings, views and opinions, and to explore their knowledge, values and attitudes. This reinforces the speakers’ responsibility for themselves and is essential for helping them towards greater responsibility for their own health choices. To practise listening skills work on Exercise 10.1.

EXERCISE 10.1

Learning to listen

Work in groups of three to six people. Appoint someone as a timekeeper.

1. Person A speaks for 2 minutes, without interruption, on a subject of her choice to do with work or other interests (for example, sensible drinking guidelines, keeping fit and active, pets, holidays). Everyone else in the group listens, without interrupting or taking notes.

2. Person B repeats as much as she can remember, without anyone else interrupting. Person B may not:

– add anything extra to what A said

– give interpretations (for example ‘It’s obvious from what she said that …’)

– give comments (for example ‘She’s just like me …’).

3. A, and the rest of the group, identify what was inaccurate, forgotten or added.

4. Repeat, with a different topic, until everyone has had a turn at being A and B.

5. Discuss the following questions:

– What helped me to listen?

– What helped me to remember?

– What hindered my listening?

– What hindered my remembering?

– What did I learn about myself as a listener?

Enabling People to Talk

The main task of the listener is to encourage and enable someone to talk. There are several useful techniques, as follows.

See also Chapter 14, section on strategies for decision making, which discusses counselling skills.

Giving an invitation to talk

To get someone started it may be helpful to give out a specific invitation to talk. Examples are:

‘You don’t seem to be your usual self today. Is something on your mind?’

‘Can we talk some more about that matter you raised briefly at yesterday’s meeting?’

‘You look worried – are you?’

Giving attention

This means listening closely to what is being said, and being fully aware of all the channels of communication, including nonverbal behaviour. It requires effort and concentration to listen hard and give full, undivided attention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access