Introduction

In this chapter we introduce you to some of the complexities that are involved in delivering food to our tables and some of the factors that you need to consider when offering meals to your patients/clients. We first discuss some of the current policies that affect how and where food is produced and sold. We also consider the different factors that influence what we eat. By understanding how socioeconomic factors impact on the extent to which people can choose what food they can grow and what food is available to them to eat, you will begin to appreciate the difficulties that many people have when they want to eat a healthy and nutritious diet.

We also introduce you to some of the different nutritional components of a healthy diet and how they promote health and well-being, as well of some of the problems that might occur if there is deficit in the diet or if there is a malfunction of the digestive system. To do this we briefly introduce you to the structure and function of the gastrointestinal system.

In the last section of the chapter, we introduce you to the important dietary needs of different groups of people through their lifespan. Throughout the relevant sections of this chapter we use examples to illustrate potential risk factors. We hope you will use this chapter as a starting point to find out more about how nutrition and disease are related and to use specialist texts to under-stand how to help people with specific dietary needs. You will find some suggestions in the supplementary reading list at the end of the chapter. You might also find it helpful to read the latest research regarding food and nutrition on the government website (www.food.gov.uk).

Food has a social meaning

Food is made up of substances that we eat or drink and are digested and absorbed to help the body grow and then to function effectively by maintaining its cells, tissues and organs in good repair. We are describing nutrition as all the macro- and micro- (at the level of the cells in the body) processes that help us to ingest and assimilate food into our cells. The Department of Health (2003a) defined a key responsibility of nurses as ensuring that patients/clients are ‘enabled to consume food orally which meets their individual need’. This implies that nurses must be knowledgeable about the important components of a healthy diet, as well as be sensitive to specific needs of their patients, and to take responsibility for ensuring their patients are able to eat and drink while under their care.

Food plays an important part in our social lives and in our spiritual lives, with several religions using food as an important symbol in their rituals, which provide guidelines on food that is acceptable or forbidden. This wider meaning of food needs to be acknowledged when caring for people in hospitals or institutions, or even in their own homes. With so many people relying on external agencies to provide their food ready-prepared, the social and religious aspect of food is often overlooked.

In times of civil war, famine and disasters that involve thousands and sometimes millions of people, public attention is focused on the social processes surrounding food production and consumption and the complexities involved in providing and delivering food. Publicity surrounding food production as a commercial and industrial activity has also raised awareness of the conditions under which some food is produced.

Another perspective on food as a commodity is the way it has been used to signify the social standing of both consumers and producers. For example, eating jellied eels or oysters used to be associated with the poor in England; then, when these foods became scarce, they were seen as the food of the wealthy. In some countries, being able to eat meat every day is often seen as a sign of wealth as most of the population do not have the resources to own animals or to buy meat. Thus, if they have the necessary resources, they rely on home-grown vegetables and fruit for their dietary staples. In other countries, many people are not so fortunate. Those who have access to land can enjoy a more secure life, and their ability to consume particular foods demonstrates their social status and thus power to acquire such food.

So you can begin to recognize that the social meaning of food goes beyond the rudimentary production/consumption process for physical survival, and that food is a marker of human social activity and identity, distinguishing people’s social status, religious affiliation and cultural practices, and distinguishing those in society who are politically powerful, empowered by their political state or those who are powerless. For the powerless who are struggling to find sufficient food to stave off starvation, irrespective of whether their food is nutritious, there is little choice about what they eat. Their plight contrasts starkly with those populations whose dietary needs can be met relatively easily but because of external influences are struggling to balance the tension between seeking out food that is novel while living in fear of food that might be harmful (Fischler 1980, cited in Beardsworth and Keil 1997). In Western society, where the organization and management of food production and food availability is managed predominantly by large commercial organizations, the challenge is to ensure that food is actually healthy rather than causing disease. Many diseases affecting people in Western societies are attributed to the high content of fat, salt and sugar in many pre-prepared food products.

In post-agricultural societies, many people have the luxury of choosing the origin, quantity, type and content of what they consume. The White Paper on public health (‘Choosing health: making healthier choices easier’), published by the Department of Health (2004), states that people want to be healthy. Throughout history, societies have experienced shortage and abundance of food. With greater awareness of the worldwide economy, there is the dichotomy of societies experiencing extreme shortages and famine, whilst others have excess. Although, because of climatic and political reasons, this may always have been the case, the 20th century was probably the first to have the resources to eliminate starvation, but this has not been done (Leather 1996).

Food policy

Food policy

Food policy embraces all those policies affecting food, food economy, supply and demand. Food policy is concerned with the global market, international laws and regulations governing the selling of food (Caraher 2000). As Lang & Heasman (2004) note, there is no one food policy or one food policy-maker, but that food policy-making is a social process as well as being highly politicized and contentious.

In the UK in the 1960s and 1970s, food policy was aimed at food security, ensuring that everybody had enough to eat – a legacy from the 1939–1945 world war when governments had struggled to ensure there was sufficient food for everyone to have their essential nutritional needs met. This was achieved by imposing a system of rationing essential foodstuffs, such as meat, eggs, butter, sugar and tea. By contrast, a world food crisis between 1972 and 1974 highlighted the global availability of, and access to, food. Maxwell & Slater (2004, p 3) argued that concern about food security is not sufficient and we need to extend attention to food policy. The lack of a coordinated approach to food reflects the causes of the changes in the food system and food policy. These are driven by urbanization, technical change, income growth, lifestyle changes, mass media and advertising and also fluctuating changes in relative food prices (Maxwell & Slater 2004, p 30). Such shifts are bound to lead to battles of interests, knowledge and beliefs (Caraher 2000, p 429; see also Lang & Heasman 2004). Successive governments in the 1980s and 1990s were in favour of self-regulating markets and food industry. As Caraher (2000) points out, cheap food was produced at the expense of quality and that led to food safety being compromised. Examples of this are the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) crisis, foot and mouth outbreaks in cattle, swine fever and more recently avian influenza. Despite unsound practices, such as condemned meat being resold, such practices have continued during subsequent governments (Caraher 2000). These examples highlight the difficulties of monitoring food production and the level of scrutiny required to ensure that only food that is fit for human consumption is sold.

Baggott (2000, p 193) noted that pressure for changes in regulations governing food safety and nutrition and calls for better health education resulted in demands for greater regulation of commercial activities, with improvement in standards. Despite this, there are ‘powerful counter-pressures’ that inhibit more-informative food labelling and allow the continued use of food additives. These commercial interests also favour international free-trade agreements (Baggott 2000, p 194).

Food policy and politics

In recent years, there have been a number of publications focusing on where our food comes from, how is it produced and how it is processed and what the politics of producing and selling food are (see, for instance, Lang & Heasman 2004, Lawrence 2004, Schlosser 2002). Schlossers’s (2002) account of the food industry practices in the USA makes worrying reading. We get the impression that customers and consumers have very limited choice or control over the fundamental quality of food. Lang & Heasman (2004) and Lawrence (2004) likewise have taken an in-depth look at the interests involved in food production and processing with a view to future developments. Lang & Heasman (2004, p 277) refer to the Nordic countries where health interests have made an impact on policy and where ‘public and environmental health can be fused with food and agricultural policy’. This means that the known health implications of food eaten by people are taken into account when formulating policies as a proactive measure in order to minimize harm to those not yet affected by certain practices. So, for instance, the North Karelia Project in Finland in the early 1970s was initially a response to one of the highest coronary heart disease rates in the world, but which resulted in not only people being asked to change their eating habits, but the food industry response was to offer low-cholesterol options in food available. Thus, for example, fat-free and semi-skimmed milk came about. The implications of the project have been far-reaching in many ways, and not always in ways that could have been anticipated (see, for instance, Lang & Heasman 2004, Puska 2002, p 5–7).

Modern society and food policy

In many Westernized, post-agricultural societies, the way food is produced has changed radically. Many European nations (for example) are no longer able to produce sufficient food for their population and, as a result, other nations supply them with their staple and supplementary foods. This creates a dependence that has led to the Common Agricultural Policy, which seeks to determine which countries will be the main producers of food and which will become the main purchasers of food. One consequence of this has been the huge distances that some foodstuffs have to be transported to the purchasers (see Activity 8.1).

Activity 8.1

When you next go shopping for food, read the information on the packaging, or on the display card, to find out the country of origin of the foodstuffs listed below. Don’t worry if there are several brands or types of the foodstuff; it is interesting to see whether they come from the same country.

• Rice.

• Flour.

• Sugar.

• Apples.

• Potatoes.

• Carrots.

• Chicken.

• Beef.

If the food item is available in different forms (e.g. organic or otherwise), see if it is available from more than one country. (NB: If the country of origin is not on the food label, you may find that the supermarket has a website giving this information.)

Consider how many food miles have been used to bring these products to your shop.

Consider whether any of them could have been grown in this country.

Lifestyle and food policy

Another factor that is impacting on the food we eat is the change in lifestyle that has taken place in many post-agricultural societies and countries. A significantly larger percentage of the population now live and work away from agricultural work, food production and the primary marketing of food. With the change in the structure of these societies, people tend to eat meals that have not been prepared at home but which have been purchased. More people tend to eat processed food from supermarkets rather than buying staple food at local outlets and using it to cook their own meals at home. With so much mass production and consumption of prepared food, the risk of contamination of such products is much greater, leading to increased concerns about food safety.

One consequence is ‘cash crop’ farming in poorer countries for consumption in richer countries, sometimes for out-of-season vegetables and fruit. A ‘cash crop’ is food that is grown to sell (probably for a consumer many miles away) to make a profit in cash, rather than growing food for the farmer’s own family or community. Prawn farming is an example. Intensive farming of prawns for export has caused untold damage. Not only has this resulted in environmental pollution, food shortage for the local poor populations in South-East Asia and South America as natural fish stocks have been destroyed or depleted, but people in Western countries end up eating prawns grown with the help of antibiotics and growth hormones (Lawrence 2004).

As a result of the change to the global production and management of food, food has become a commodity whose value see-saws from day to day depending upon financial market fluctuations. So food policy is no longer the province solely of ministries of agriculture but is discussed in ministries and organizations concerned with trade and industry, consumer affairs, food activist groups and non-governmental organizations (Maxwell & Slater 2004).

The food industry

In our commercial, capitalist world, companies compete with each other to establish a market for their goods and to achieve profit margins that enable expansion of the industry. Food manufacturers are equally engaged in these kinds of trade wars, and market products designed to attract the maximum number of purchasers.

Several food manufacturers have been criticized for the nutritional quality of their products, or in the case of alcoholic drinks, their target markets (see, for instance, Lang & Heasman 2004, Schlosser 2002). Some companies have responded by changing their products to reflect current trends in eating healthy foods, such as offering salad alternatives in the range of fast foods available. Selling food products as having a nutritional value is beginning to become more widespread in supermarkets as a marketing strategy; for example, ‘free from’ ranges for people with special dietary needs, or the increased sales in organic food products indicates that trends can be changed if there is sufficient popular support, often as a result of television programmes. There seems to be some ambiguity in the way the public approaches food. On the one hand, people are aware of risks involved in food consumption and are knowledgeable of the global food scarcity; on the other hand, there is the competition for consumers and shoppers. This may explain the so-called ‘price wars’ between the major supermarkets (see Lawrence 2004, for example).

The huge financial power of the international food industry can lead to a level of political influence that may not work in the best interests of the population (Schlosser 2002) and even that major democratic governments are unable to control. For instance, Schlosser (2002) argues that the US Congress should ban food advertising directed at children and that tougher food safety laws should be passed (see Activity 8.2). However, moves such as these have been bitterly opposed.

Activity 8.2

• Who is the focus of food advertisements?

• Watch some commercial children’s television (Saturday morning is a good time).

• What are the implications of the advertisements that are promoted at this time?

• What might be the impact on children’s health if they have a diet of these advertised foods?

Obtaining food

Choice and consumption of food in the developed countries reflect the powerful economic position of these countries. What people eat depends on availability and acceptability (Fieldhouse 1996) of foodstuffs. Whilst poverty may be associated with people at risk of dying from lack of food, in Western countries people tend to experience relative poverty where lack of money and food and other consumables compares unfavourably with other people’s purchasing power. People on low incomes spend proportionately more on food than do better off people (Beardsworth & Keil 1997). In the USA, the richest country in the world, it was estimated that 12 million families in 2003 worried they did not have enough money for food and in nearly 3.8 million families someone skipped meals because they could not afford them. These figures represent a 13% increase on year 2000 (Center for Family Policy and Practice 2004).

The economies that people in poverty have to exercise can override concerns about the quality of food. Whether eating healthy food is more expensive than less healthy alternatives is debatable and depends on what ingredients are used. For instance, cheaper food has to be acceptable in terms of cultural and religious customs and beliefs, as well as palatability; people also need appropriate cooking facilities and money for fuel to make use of the cheaper cuts of meat or pulses that need longer cooking times. People used to be able to make use of seasonal fruit and vegetables that were cheaper at times of harvest. The way in which market prices and profits are determined seems to have negated such seasonal advantage in this country.

Food shopping commands a large proportion of weekly income, particularly of those on low incomes. Savings on food release money for other expenditures. Working out the cost of a ‘healthy’ or ‘nutritious’ food basket can be complicated. Different countries have a slightly varying number of basic food items. Whether the food is imported or locally grown, and thus the length and type of transport, add to the cost. Different stages of production and processing, whether organic or conventional, and locally or globally sourced, also affect the real cost of the food basket (Center for Family Policy and Practice 2002). Activity 8.3 explores concerns regarding buying food.

Activity 8.3

Spend a few moments jotting down the factors that influence your choices when shopping for food.

• Are these factors associated with food cost, distance from the food store, the dietary preferences of you and the people you are shopping for?

• What foods on your list are seasonal?

• When you go to your local food shop and get to the checkout, look at the food baskets of your fellow shoppers. To what extent do they differ from the content of yours?

• What are the chief foodstuffs that they are buying?

• How do these foodstuffs relate to your concept of a healthy diet?

Whilst it is possible to improve diet without spending excessive amounts of money, food is a discretionary item of expenditure (Baum 2002) and often it constitutes the first part of the household budget to be reduced in order to save money. People with low incomes eat a ‘flexible’ diet (Walker 1993). This means variability in quality and quantity. Cheaper meat products and processed food tend to be higher in fat, sugar and salt content, unlike healthier vegetables, fruit and lean cuts of meat, grain and cereal.

Most people in the UK purchase their food from shops with no knowledge of the producer. The consumer is therefore reliant on the information provided by the producer about food. In the UK, £800 billion is spent on fruit juice, very likely because it has a healthy image. But, in 1993, a company in the USA was fined (and the owner imprisoned) for selling adulterated fruit juice as 100% fresh (Patel 1994). ‘Flavor Fresh’ was concentrated, then diluted, had sugar, cheap citric acid and amino acids added with pulpwash and preservative. The product itself was not illegal; the problem was in the labelling, which should have said ‘made from concentrate’, as well as declaring the other additives. However, as the producer can charge 20% more for a pure product it may be tempting to withhold full information. This case is not unusual. Between 1986 and 1994 the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) successfully prosecuted 10 companies. Prosecution usually occurs as a result of employees whistle-blowing, or occasional random tests.

Food Standards Agency of the UK

In the UK, the government’s food policy is based on advice from the Food Standards Agency (FSA), which was established in 2000 following the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) epidemic. The FSA is the only body that deals with the quality of our food, which was previously the responsibility of MAFF (Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food 2002), which is also concerned with farm incomes. The FSA is answerable to the Department of Health, although its (quite generous) budget comes from MAFF (MAFF 2002).

The functions of the FSA include:

• Commissions research (£25 m).

• Publishes advice to ministers.

• Raises money from the food industry.

• Defines balanced diet; asks health ministers to overrule MAFF.

• Offers guidelines to consumers and companies about labelling.

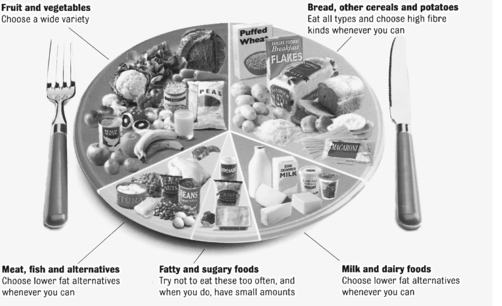

The FSA works at three levels: at a national and international level to influence food regulations; at a community level to influence people’s food choices to become more health orientated (see Figure 8.1); through health education campaigns.

|

| Figure 8.1The balance of good health ‘plate’.(Reproduced with kind permission from the Health Education Authority 1994.)Health Education Authority |

Food labelling

Labelling of foodstuffs is not compulsory, unless specific claims are being made (e.g. ‘low fat’ or ‘high fibre’). However, many food firms recognize that labelling their products increases public confidence. Legislation requires that information about nutrients must be provided in one of two ways as outlined in Box 8.1.

Box 8.1

Labelling of nutrients that must normally be tabulated on food packaging

Group 1: energy in kilojoules (kJ) and kilocalories (kcal), and the amount of protein, carbohydrate and fat in grams (g).

Group 2: as for group 1, but the carbohydrate is divided into sugars and others, fat into saturated and unsaturated, and fibre and sodium.

Vitamin and mineral content: can only be identified if it is in significant amounts, such as a proportion of the recommended daily intake (or Reference Nutrient Intake).

Information must be given per 100 g or 100 ml, and the overall portion size or number of average portions must be stated on the packet.

Lists of ingredient might not be comprehensive; for example, ‘raising agents’ or ‘flavourings’ need not be fully listed. This is a particular concern for vegans/vegetarians and for allergy sufferers as the ingredients they wish to exclude may be omitted from the list. (The FSA would like to address this issue.) Many of the terms used in packaging have no meaning (e.g. ‘fresh’ or ‘traditional’).

Where foodstuffs are being sold for a particular nutritional use (known as PARNUT foods), the labelling regulations are more strict, although these are sometimes open to controversy as they could mislead people into believing they are eating food that is recommended for their condition. An example could be diabetic jams, when it is probably healthier for the diabetic person not to eat products with a high glycaemic index (see the Food Standards Agency 2004).

The FSA would like to make labels less confusing. For instance, ‘90% fat-free’ can be interpreted in several ways and a more accurate form of labelling, such as 10% fat content, would be safer for consumers. Similarly, labelling a product as ‘fat-free’ or ‘low fat’ should have a specific recommended meaning such that low fat would mean 3 grams per 100 grams and fat-free would mean less than 0.15 gram per 100 grams.

The FSA would also like information to be provided regarding the presence of potential allergens and to clarify labelling on genetically modified (GM) foods as well as improved strategies to detect such substances.

Marketing terms such as ‘fresh’ and ‘traditional’, which actually mean nothing, are also descriptions on which the FSA would like more clarity and restriction. There is no restriction on how food companies can name their product, or promote its image or promote a food as being ‘healthy’.

The meaning and function of food

Food represents more than just bodily fuel and nutrition. Lupton (2000) notes that the aspects of food found most pleasurable and valuable by an Australian study were to do with nostalgia and tradition, and the social enjoyment and happiness of being together with family. The social nature of eating together signifies the importance of such occasions beyond the basic function of food. In health care practice, the positive feelings and sociability that eating together engenders could be enhanced by encouraging mobile patients in hospitals to eat in the day room, depending on the facilities. In nursing homes, meals are often served to residents in a communal setting with the aim of encouraging social interaction.

How importantly people rate health considerations in choosing, preparing and eating meals is reflected in Lupton’s (2000) study. Nearly all the participants indicated a strong concern as to the ‘healthiness’ of meals and seemed to make a connection between ‘healthy’ and home cooking, which covered basic nutritional needs with ‘variety’ and ‘balance’ in food choices. A significant point about healthy meals was that they were seen as a major aspect of family relationships and beginning a cohabitating relationship. These relationships seemed to mark more home-cooked and balanced meals (Lupton 2000). We can draw a conclusion that the social context of food preparation and consumption bear significantly on the type of food (quality) prepared and the pleasure-enhancing way it is eaten. Thus a ‘proper meal’, consisting of meat and vegetables, brings together the ideal of a ‘close family’ and health (Lupton 2000). Kemmer (2000) notes that, through food men and women can show their feelings for one another and also that traditional gender roles are expressed in food preparation. However, the increasing number of women in paid employment outside the home seems to have encouraged men to get involved in meal preparation more often (Horrell 1994, cited in Kemmer 2000).

It might be tempting to blame women for the falling standards in our nutrition. However, the picture is more complex than that. Social change affects the way people live their lives. Many women feel that they have little choice in going to work and that in so doing they are, indeed, providing for their families.

Contemporary cookery books and the cooking industry reflect trends in our attitude to food and cooking. There has been a whole industry burgeoning around cooking. Cookery books are amongst the bestsellers in bookshops, and the television channels are competing with each other for viewers for their cookery programmes. However, their impact on promoting home cooking has not been studied.

Most people have at least some opinion as to how food should be prepared, served and eaten. They also have a view about what foods are appropriate on different occasions. Some have a religious significance and some religions have strict dietary rules (see Box 8.2), in some cases originally designed to protect people from food poisoning.

Box 8.2

Religious dietary laws

Many religions and cultures forbid the taking of pork. The reasons for this are complex and varied. Pork is likely to lead to problems with food poisoning, which is a particularly serious matter in hot climates. Furthermore, there is an incident described in the Bible where Jesus sends demons into a herd of pigs (see Matthew Chapter 5, verses 8–14). For these and possibly other reasons people may believe that pork is ‘dirty’.

Many Muslims teach that some food, like pork, is ‘harram’ or un-pure. In order to be ‘halal’ or suitable for eating, food has to be correctly prepared. In the case of meat, the animal has to be slaughtered in a particular way. The Jewish term for food that is satisfactory to eat is ‘kosher’.

Christians, particularly Roman Catholics, teach that Friday is a time for special meditation and prayer. Part of this may include eating more simply, often by excluding meat, or substituting meat with fish. This is why many people choose to eat fish on a Friday, even if the original rationale is forgotten.

Many religious people include periods of fasting, believing that this assists in prayer and concentrating on one’s soul. Muslims teach that the month of Ramadan is a time when food should not be taken in daylight hours. The time of Ramadan varies, and it can be quite arduous if it falls in the summer. Christians used to use Lent as a time for fasting, or abstaining from animal products, largely because they were scarce.

These periods of fasting are often followed by celebrations, such as Easter, and, in Islam, the Eid. At these times, eating forms an important part of the festivities.

Most religions make exceptions to the fasting requirements for those who are ill, lactating, menstruating or pregnant.

As a nursing student, you will need to ask your patients/clients (or their family) about their beliefs and preferences, and be guided by this. Most people know that eating is essential to life, and for many people eating in the correct way is just as important. It may be useful to consider the point that, although the rules may be important for various reasons, including safe eating, it is not always clear if they are practised for religious reasons or whether they are culturally constructed.

Dietary preferences

Many people choose to reduce or omit animal products from their diet. Such people are often referred to as vegetarians or vegans. The rationale for vegetarianism is varied and will influence the exact type of vegetarian diet chosen. For example, some people are concerned about animal welfare, but may perhaps eat meat if they are satisfied about the standards of animal husbandry (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals 2004).

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals has started the ‘freedom foods’ scheme, which identifies meat derived from animals in cases where the farmer has met certain criteria. Others feel that the costs of raising an animal to eat makes it morally wrong when so many people cannot get enough to eat; these people may accept meat that has been raised in areas, such as high hill land, that are unsuitable for arable purposes. Still others believe that fruits and vegetables are particularly healthy and choose to eat vegetarian or vegan food, although some may accept meat as an occasional treat or as a courtesy. Many devout religious people believe it is wrong to kill any sentient being and observe a strict vegan or vegetarian diet, whilst others who find it difficult to obtain meat that has been treated according to religious laws, or who are unsure about how the meat has been prepared, choose a vegetarian diet.

The food we need

So far, we have discussed the social and cultural aspects of food and nutrition. In this section we consider what we mean by nutrition. Nutrition is concerned with the quality of our diet and whether it will help us sustain a healthy lifestyle or whether it will lead to physical and emotional problems. The World Health Organization (cited in Lawrence 2004) reported that 60% of deaths around the world are related to increased consumption of fatty, salty and sugary foods arising from changing dietary patterns (Lawrence 2004). This indicates that the changes that have taken place in Western diets are also taking place on an international and worldwide scale, due to the marketing and distribution patterns of international food companies. The same kind of dramatic rise in consumption of fats and sugars has occurred in China and India as these countries have moved away from an agricultural economy and towards greater industrialization and urbanization, and thus increased disposable income of its population (Lawrence 2004). These changes in dietary patterns are resulting in a rise of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity. By contrast, approximately 1.2 billion people in the world have too little to eat (Kew Magazine 2005, Lawrence 2004).

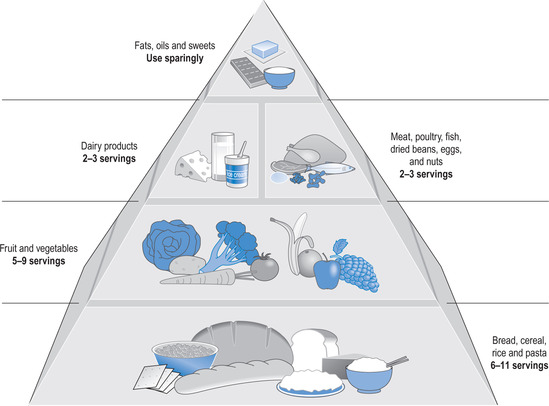

So what are the essential components of a healthy diet and where can they be obtained? Most essential components of a diet can be classified into micronutrients and macronutrients.

The micro-elements are the vitamins and minerals that are essential for a healthy life and which many people believe they can take as supplements to their normal diet as a strategy to increase their health or reduce the incidence of illness. Research so far has discovered that these micro-elements are responsible primarily for the normal development and functioning of cells.

The macro-elements are substances known as proteins, carbohydrates, fats or lipids. These macronutrients form the key building-blocks of cells; they also provide energy for the cells to function and consequently for the body to function, and so for you to live, breathe, digest, think and move (Figure 8.2).

|

| Figure 8.2The main food groups and their recommended proportions per day within a balanced diet.(Reproduced with kind permission from Waugh & Grant 2006.) |

In the following sections, we first explore what is meant by energy then discuss the different nutrients that are needed in your diet.

Energy

Have you ever noticed that you feel warm while eating or that, if you are very hungry, you often feel cold and more sensitive to pain?

Energy is important because we need it for almost all functions of the body. On a macro-level these daily functions require the heart to pump blood around all the tissues in the body, the lungs to absorb oxygen and to excrete carbon dioxide, the kidneys to filtrate blood and form urine, the intestines to absorb and excrete foods, the muscles to contract and expand and the brain to function. Each of these vital organs produces other substances that are also essential to the good functioning of the body.

The basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the amount of energy required by the body when at rest (but not asleep). Additional activities such as moving and even thinking require extra energy. The BMR is not fixed as it will go up in extreme cold temperatures as the body increases its use (burning) of energy to keep the body temperature constant at the optimum temperature for its cells to function (37°C), and also for eating. When someone fasts or is starving, their BMR reduces and the person may feel cold and sleepy as the body tries to save energy to conserve its resources for essential cellular function (you can read more about temperature regulation in Chapter 9). The change in BMR caused by eating or not eating is important as it explains why starvation diets rarely work. The effect of eating can be seen particularly when taking breakfast, as the food intake causes the BMR to rise and thus ‘kick starts’ the metabolic functions of the body. Pollitt (1995) argues that children of school age who have eaten breakfast are able to outperform those children who have not. Probably the same is also true for adults, which is why almost all effective weight-loss regimens include breakfast.

So what is energy?

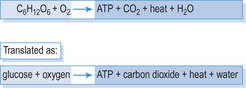

Energy is the ability (or potential ability) of the body to function effectively and to enable it to carry out our daily activities. Most of this body work is conducted within the millions of cells that make up our bodies. Within each cell there are special structures called ‘mitochondria’ (singular: ‘mitochondrion’), often known as the power house of the cell because of their essential role in undertaking the activity of metabolism (Figure 8.3). In order for a cell to carry out its metabolic work, it usually requires energy. The mitochondria use a particular compound that facilitates this energy production; this compound is called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The mitochondria can manufacture ATP by using oxygen that has been delivered via the red blood cells to the tissue cells, along with another product of nutrition, glucose. (Sometimes the mitochondria produce energy using different products, but this normally only happens as an emergency if there is a shortage of oxygen and glucose.) In the process of manufacturing ATP, the mitochondria also produce several waste products, one of which is energy in the form of heat, another is carbon dioxide and another is water. The water helps transport the carbon dioxide out of the mitochondria and the cell into the capillary blood from where it is transported via the veins, through the right side of the heart and then on to the alveolar capillaries in the lungs to be excreted in the breath.

|

| Figure 8.3a typical cell showing the mitochondria.(Reproduced with kind permission from Waugh & Grant 2006.) |

The process of ATP manufacture is called a metabolic pathway; Figure 8.4 summarizes this process. Energy production is carried out in the mitochondria of all cells, except red blood cells (because red blood cells only have minimal energy requirements).

|

| Figure 8.4Production of energy in the mitochondria. |

Humans are described as being in energy balance if the energy they are taking in through their diet is about the same as the amount of energy being used. So sports people prepare themselves before a sporting event by taking large quantities of high-energy foods. As a result of an evolutionary response to times of hunger, the body has the ability to store energy reserves during times of plenty, usually in the form of adipose tissue (fat) deposited under the skin, or in the buttocks, or over the abdominal organs. If inadequate energy-providing foods are taken, for example during periods of famine or food shortages, or starvation (such as in hospitals), then the body has the ability to maintain its cellular function, and thus life for a period of time, by drawing upon its reserves until they are exhausted, when death will take place.

Carbohydrates and proteins both yield approximately 17 joules (J) of energy for each gram (g) of food consumed. Fats, and also alcohol, yield 30 J/g, and so are a dense source of energy.

Macronutrients

Macronutrients are essential for the effective development of cells and tissues and they all have the ability to be used for energy production, although they also have different and unique functions in a healthy diet.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates all contain carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. There is a wide range of foodstuffs that are high in carbohydrate and they are the most plentiful. The main purpose of carbohydrates is to provide the necessary substances for energy production and they are the simplest form of nutrient to transform into energy. Carbohydrates are subclassified, according to the size of the molecules, into monosaccharides, disaccharides and oligosaccharides. These all taste sweet and are present in almost all sweet-tasting foods, including cakes, sweets and fruit (Table 8.1).

| Type of carbohydrate | Number of carbon atoms or monosaccharides | Examples | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monosaccharide (a one-sugar unit) | Six carbon atoms: known as a hexose | Glucose | |

| Five carbon atoms: known a pentose | Fructose | ||

| Disaccharide | Two monosaccharides chemically bound together | Sucrose (consists of glucose and fructose) | Table sugar |

| Lactose (consists of galactose and glucose) | Milk | ||

| Maltose (consists of two glucose molecules) | Many cereals | ||

| Oligosaccharide | Composed of two, three or four monosaccharides |

Polysaccharides are large complex molecules composed of many monosaccharides. They do not taste sweet. The chief examples are amylose and amylosepectin, which together constitute starch (found in plants) and glycogen (found mainly in animals). In the Western diet the most important sources of polysaccharides are potatoes, rice and wheat products such as bread and pasta.

Most carbohydrates are at least partially broken down in the gastrointestinal tract to mono- and disaccharides. However, the rate at which this takes places varies and this is very important for human health. Some carbohydrates are very quickly and easily broken down to mono- and disaccharides, whereas others take much longer. The speed at which dietary carbohydrate appears as blood glucose is referred to as the glycaemic index. Foods with a high glycaemic index are quickly broken down and lead to a rapid rise in blood sugar, which provides an energy burst, followed by a rapid drop in blood sugar, leaving the person hungry. Those foodstuffs that take longer to be digested by the gastrointestinal system are identified as having a low glycaemic index. They are absorbed into the bloodstream more slowly and so lead to a slower but more sustained rise in blood sugar. Normally it is better to choose foods with a low glycaemic index, as they provide energy over a longer period of time. Foods with a high glycaemic index can cause wide swings in blood sugar, which might lead to long-term health problems. A simple guide to high or low glycaemic foodstuffs is the size of the molecules. Most foodstuffs with large molecules have a low glycaemic index, but there are important exceptions to this. Note, for instance, that baked and roast (but not boiled) potatoes have a high glycaemic index, and so would lead to a rapid increase in blood sugar, whereas milk and yoghurt have a low glycaemic index, leading to a slower and more sustained rise in blood sugar (see Table 8.2). Try Activity 8.4 and calculate what your typical daily glycaemic index intake might be.

| Source: BUPA website (www.bupa.co.uk/health). COH, shorthand for carbohydrate. | ||||||||||||||||

| High-GI foods | Moderate-GI foods | Low-GI foods | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI > 59 | COH (g/portion) | GI = 40–59 | COH (g/portion) | GI = 1–39 | COH (g/portion) | |||||||||||

| Breakfastcereals | ||||||||||||||||

| Cornflakes | 84 | 26 | All Bran | 42 | 19 | |||||||||||

| Rice Crispies | 82 | 27 | Sultana Bran | 52 | 20 | |||||||||||

| Cheerios | 74 | 23 | Porridge (with water) | 42 | 14 | |||||||||||

| Shredded Wheat | 67 | 31 | Muesli | 56 | 34 | |||||||||||

| Weetabix | 69 | 30 | ||||||||||||||

| Grains/pasta | ||||||||||||||||

| Couscous | 65 | 77 | Buckwheat | 54 | 68 | |||||||||||

| Brown rice | 76 | 58 | Bulgar wheat | 48 | 44 | |||||||||||

| White rice | 87 | 56 | Basmati rice | 58 | 48 | |||||||||||

| Noodles | 46 | 30 | ||||||||||||||

| Macaroni | 45 | 43 | ||||||||||||||

| Spaghetti | 41 | 49 | ||||||||||||||

| Breads | ||||||||||||||||

| Bagel | 72 | 46 | Pitta bread | 57 | 43 | |||||||||||

| Croissant | 67 | 23 | Rye bread | 41 | 11 | |||||||||||

| Baguette | 95 | 22 | ||||||||||||||

| White bread | 70 | 18 | ||||||||||||||

| Wholemeal bread | 69 | 16 | ||||||||||||||

| Pizza | 60 | 38 | ||||||||||||||

| Crackers, biscuits and cakes | ||||||||||||||||

| Puffed crispbread | 81 | 7 | Digestive | 59 | 10 | |||||||||||

| Ryvita | 69 | 7 | Oatmeal | 55 | 8 | |||||||||||

| Water biscuit | 78 | 6 | Rich Tea | 55 | 8 | |||||||||||

| Rice cakes | 85 | 6 | Muffin | 44 | 34 | |||||||||||

| Shortbread | 64 | 8 | Sponge cake | 46 | 39 | |||||||||||

| Vegetables | ||||||||||||||||

| Parsnip | 97 | 8 | Carrots | 49 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Baked potato | 85 | 22 | ||||||||||||||

| Boiled new potato | 62 | 27 | ||||||||||||||

| Mashed potato | 70 | 28 | Boiled potato | 56 | 30 | |||||||||||

| Chips | 75 | 59 | Peas | 48 | 7 | |||||||||||

| Swede | 72 | 1 | Sweetcorn | 55 | 17 | |||||||||||

| Broad beans | 79 | 7 | Sweet potato | 54 | 27 | |||||||||||

| Yam | 51 | 43 | ||||||||||||||

| High-GI foods | Moderate-GI foods | Low-GI foods | ||||||||||||||

| GI > 59 | COH (g/portion) | GI = 40–59 | COH (g/portion) | GI = 1–39 | COH (g/portion) | |||||||||||

| Pulses | ||||||||||||||||

| Baked beans | 48 | 31 | Butter beans | 31 | 22 | |||||||||||

| Chick peas | 33 | 24 | ||||||||||||||

| Red kidney beans | 27 | 20 | ||||||||||||||

| Green/brown lentils | 30 | 28 | ||||||||||||||

| Red lentils | 26 | 28 | ||||||||||||||

| Soya beans | 18 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| Fruit | ||||||||||||||||

| Cantaloupe melon | 65 | 6 | Apricots | 57 | 3 | Apples | 38 | 12 | ||||||||

| Pineapple | 66 | 8 | Banana | 55 | 23 | Dried apricots | 31 | 15 | ||||||||

| Raisins | 64 | 21 | Grapes | 46 | 15 | Cherries | 22 | 10 | ||||||||

| Water melon | 72 | 14 | Kiwi | 52 | 6 | Grapefruit | 25 | 5 | ||||||||

| Mango | 55 | 11 | Peaches (tinned) | 30 | 12 | |||||||||||

| Orange | 44 | 12 | Pear | 38 | 16 | |||||||||||

| Papaya | 58 | 12 | Plum | 39 | 5 | |||||||||||

| Peach | 42 | 8 | ||||||||||||||

| Plum | 39 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Sultanas | 56 | 12 | ||||||||||||||

| Dairy products | ||||||||||||||||

| Ice cream | 61 | 14 | Custard | 43 | 20 | Full cream milk | 27 | 14 | ||||||||

| Skimmed milk | 32 | 15 | ||||||||||||||

| Yoghurt (low fat fruit) | 33 | 27 | ||||||||||||||

| Drinks | ||||||||||||||||

| Fanta | 68 | 51 | Apple juice | 40 | 16 | |||||||||||

| Lucozade | 95 | 40 | Orange juice | 46 | 14 | |||||||||||

| Isostar | 70 | 18 | ||||||||||||||

| Gatorade | 78 | 15 | ||||||||||||||

| Squash (diluted) | 66 | 14 | ||||||||||||||

| Snacks and sweets | ||||||||||||||||

| Tortilla/Corn chips | 72 | 30 | Crisps | 54 | 16 | Peanuts | 14 | 4 | ||||||||

| Mars bar | 68 | 43 | Milk chocolate | 49 | 31 | |||||||||||

| Muesli bar | 61 | 20 | ||||||||||||||

| Sugars | ||||||||||||||||

| Glucose | 100 | 5 | Honey | 58 | 13 | Fructose | 23 | 5 | ||||||||

| Sucrose | 65 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Maltodextrin | 105 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

Activity 8.4

Make a list of what you have eaten over the past 24 hours. If you can remember what drinks you have had, include these in your list.

Working through the glycaemic index of foodstuffs listed in Table 8.2, determine how the different food items are categorized.

Now consider whether your dietary intake is mainly from the high, medium or low categories of the Glycaemic Index.

Consider which high-GI foodstuffs you could exchange for medium- or low-GI foods to give you more energy for longer each day.

Fibre

Fibre includes any foods that cannot be absorbed or broken down by enzymes in the human digestive tract and are usually complex carbohydrates (e.g. some forms of starch). Fibre is therefore not a true nutrient. Foods rich in fibre include most fruit and vegetables, and wholemeal foods such as brown rice and wholemeal bread. However, fibre does play an important role in regulating gastrointestinal function, and a lack of fibre can lead to constipation and other difficulties.

Proteins

Proteins are an important component of a healthy diet. They are found in a range of foodstuffs, but particularly in animal products and some pulses and cereals. High-protein foods include meat, fish, dairy products and eggs. Proteins are normally used primarily for tissue development; however, in times of shortage of carbohydrate foods, the body can convert proteins into energy. This is one of the principles of some diets.

Proteins are large, complex molecules that are made up of smaller components called amino acids. All amino acids contain nitrogen.

Dispensable and indispensable amino acids

Approximately 20 different amino acids occur in nature and these are often classified as indispensable and dispensable (previously known as essential and non-essential) amino acids. Both indispensable and dispensable amino acids are required for human health, but the dispensable amino acids can be manufactured in the liver from other amino acids. Indispensable amino acids can only be obtained from eating the appropriate foodstuffs. Of these indispensable amino acids, eight are essential for adults, and because the liver of infants is too immature to manufacture histidine, they have to have these provided in their food.

Proteins are essential for the manufacture of cells and tissues, as well as of many chemical messengers such as hormones and neurotransmitters. When people have suffered an injury, such as surgery, a burn or loss of tissue, they need additional intakes of proteins for repairing or growing new tissue.

Sources of protein

You can obtain proteins from both animal and plant sources, although the amino acid profile in animal sources is closer to what is required for humans. In fact, proteins from animal sources used to be referred to as first-class proteins, and those from plant sources as second-class proteins. However, with increased understanding of nutrition, animal proteins are now referred to as proteins of high biological value and plant proteins as proteins of low biological value. Vegetables rich in protein include lentils, potatoes, rice and legumes (peas and beans). Vegetarians and vegans who do not eat meat products can obtain the necessary range of indispensable amino acids by eating a wide variety of plant foods.

Lipids

Fats are more correctly known as lipids because they consist of two main types: fats, which are solid at room temperature, and oils, which are liquid at room temperature. Lipids are essential to bodily function and can be found in a wide range of body tissues:

• In cell membranes.

• As insulation to nerve tissue, thus enabling the electrical impulses to travel faster. The brain is largely composed of fatty tissue.

• As an essential part of the transport system for fat-soluble substances such as vitamins.

• As a vital component of some of the messenger hormones.

• As insulation to the body as a whole, and between some organs and muscles; excess fat intake is stored in these tissues as a resource in times of famine.

Lipids as an energy source

Lipids are also a rich source of energy, yielding almost twice as much energy for their weight as proteins or carbohydrates.

Most lipids in our diet and in our body are composed of triglycerides. A triglyceride molecule consists of a glycerol ‘backbone’ supporting three fatty acids. Fatty acids are (often long) chains of carbon atoms, with hydrogen atoms (and oxygen in the acid part) attached. Carbon has the capacity of chemically binding up to four other atoms. Each carbon atom will be attached to two other carbon atoms in the chain; if the remaining capacity binds hydrogen atoms, then the fatty acid is said to be ‘saturated’. If the carbon atoms have ‘spaces’ that are not occupied by a hydrogen atom, the fatty acid is said to be ‘unsaturated’.

Lipids are not water-soluble, yet the dietary intake of lipid nutrients needs to be transported in the bloodstream. This is achieved by attaching the lipids to plasma proteins, so making a lipoprotein. Adipocytes (in the adipose tissue, about half of which is subcutaneous) remove the fatty acids and glycerol from the bloodstream for up to 4 hours after a fatty meal has been eaten and store approximately 85% of the body’s energy in the form of triglycerides. The normal distribution of adipose tissue constitutes 21% of the average female body mass and 15% of the male body mass. It contains approximately 2 months’ supply of energy reserves against famine or seasonal changes. With changes in dietary habits and relative affluence in many societies, these percentages have changed considerably.

Between meals, as the blood glucose level begins to fall, the body starts to mobilize its reserves by releasing hormones such as glucocorticoids, human growth hormone and adrenaline (also known as epinephrine), which trigger the adipocytes to release glycerol and fatty acids back into the bloodstream (Martini & Welch 2005). Initially, the glycogen in the liver is converted back to glucose, but this supply is not abundant, and, with prolonged fasting, the individual will utilize adipose tissue and finally protein tissue, particularly skeletal muscle.

Recommendations for dietary lipid intake

Current recommendations state that we should take about 33% of our total energy requirements from lipid (MAFF 2002), yet most people are taking approximately 40% of their energy requirements as lipid. However, most of this (80–90%) should come from unsaturated fatty acids, and only 10% from saturated fatty acids. This is because saturated fatty acids encourage the formation of low-density lipoproteins (sometimes called ‘bad cholesterol’) in the liver, which are associated with the formation of atheroma (see below). Unsaturated fatty acids, however, are associated with the formation of high-density lipoproteins (‘good cholesterol’), which are at the least not harmful to arteries, and may even protect them. Foods that are high in unsaturated fatty acids, particularly polyunsaturated fatty acids, are usually liquids (oils) from plants or fish. ‘Fat’ from animals tends to be solid and high in saturated fatty acids.

There is some interest in the position of the first carbon to have a double bond within the unsaturated fatty acid molecule (see, for example, Small 2002). Thus, in omega-3 fatty acids the first carbon with a double bond is at the third position, counting from the glycerol backbone. The liver cannot make a fatty acid with a double bond nearer than the eighth position, so the liver cannot make omega-3 or omega-6 fatty acids; these are therefore considered essential fatty acids. Omega-6 fatty acids are reasonably abundant in the diet, and come from seeds and cereals. Omega-3 fatty acids are found predominantly in oily fish such as herring, mackerel, pilchards, salmon and sardines. For many people their dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids probably needs to be increased, particularly as a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids may offer protection from a wide range of problems, including allergies, cardiovascular disorders and even mental health problems (Small 2002). Follow Activity 8.5 and try to identify which types of lipids are in your diet.

Activity 8.5

Look in your kitchen store cupboard and in your fridge and make a list of the different types of foodstuffs, fats and lipids that you are using on a daily or weekly basis.

Check the labels to determine whether the foodstuffs contain saturated or unsaturated fats and in what proportions.

Does your diet contain mainly saturated or unsaturated fats?

What might the impact of this intake be on your health, now and in the future?

Lipids and atheroma

One of the much publicized effects of lipids in the diet is the development of atheroma. Atheroma is a condition in which a layer of lipid material develops on the inside walls of the artery. This has the effect of reducing the diameter of the lumen of the artery and so restricting the flow of blood. This causes a reduction in the flow of blood to the tissues the artery serves, and also, if the atheroma is extensive enough, raises the blood pressure throughout the circulation. These changes are clearly dangerous to the health of a child and subsequently the adult. The problem is related to the amount and nature of the lipid and fat intake rather than the inclusion of fats and lipids in the diet.

In this section we give you a brief introduction to some of the main vitamins and minerals that are essential for health, and their main sources.

Vitamins

Vitamins are organic compounds that are made by plants and some animals, but cannot be made by humans. As they are essential in small quantities for the maintenance of health, we must find them in the food that we eat. Vitamins can be classified as lipid-soluble (vitamins A, D, E and K) and water-soluble (the B group and vitamin C). This means that lipid-soluble vitamins are more commonly found in fats, such as fish oil, dairy fats and some vegetables that have a high lipid content (e.g. avocados). The body is only able to absorb lipid-soluble vitamins if it is able to absorb other fatty substances from the digestive system at the same time. Water-soluble vitamins are more vulnerable to being lost from the diet as they can leach out into the cooking water, which is why it is often better to steam green vegetables, for example, to conserve the vitamins in them.

Some people choose to take vitamin supplements, often in large quantity. If the vitamin concerned is water-soluble, this is probably harmless and may be helpful, as any excess vitamin is lost in the urine. For instance, many people take generous supplements of vitamin C, believing that it will help ward off infections, including the common cold (New Scientist 2005). There is indeed evidence that supplements may assist in reducing the length of the incidence but not reducing its occurrence.

However, taking large quantities of lipid-soluble vitamins is not recommended, as these can accumulate in the liver, and be potentially toxic.

See Table 8.3 for a brief summary of the chief sources and action of some of the vitamins discussed in the sections below.

| Vitamin | Source | Function | Deficiency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A (retinol) | Liver, dairy produce, eggs | Vision, particularly in low light | Poor vision, even blindness | Avoid excess, particularly in pregnancy |

| Folate | Offal, yeast extract, leafy green vegetables | Essential for rapidly dividing cells | Should be supplemented in very early pregnancy | |

| Vitamin B12 | Many animal, dairy and egg products | Manufacture and function of red blood and nerve cells | Pernicious anaemia | Requires intrinsic factor for absorption |

| Vitamin C | Fruit and coloured vegetables | Maintenance of connective tissue | Scurvy | Is readily destroyed by storage and cooking |

| Vitamin D | Margarine | Promotes mineralization of bones | Rickets, osteomalacia | Is synthesized from action of sunlight on skin |

| Vitamin E | Vegetable oil, nuts and seeds | Antioxidant | Rare |

Vitamin A

Vitamin A is a lipid-soluble vitamin; it is essential for the correct functioning of the eye. If there is an inadequate intake of vitamin A, the person will suffer from a loss of night vision. In many parts of the world, children’s sight has been permanently damaged by lack of vitamin A. It is not abundant in the diet, and is often taken in the form of beta-carotene, which is present in milk, cheese, carrots, cabbage, peppers and sweet potatoes. Supplementation, however, should be undertaken with caution. For instance, excessive intake of vitamin A has been associated with damage to unborn children (Kmietowicz 2003). One of the oldest skeletons found, the bones of Lucy, which were discovered in Olduvai gorge in Kenya, were found to contain high quantities of vitamin A and it is believed that she died as a result of vitamin A poisoning, probably from eating animal liver, where it is stored.

B group vitamins

These are water-soluble vitamins and all act as co-factors, which enhance enzyme activity.

Folate (which is a form of folic acid) is one of the B group of vitamins. Folate has been the subject of much interest since it was established as preventing neural tube defects in the growing embryo (Wald 1991). Other research studies have demonstrated that taking folate can reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease in older adults. In the UK, the best source of folate has traditionally been flour and therefore bread, but more recently the folate content of flour has declined, so some countries now add folate to flour and flour-based products.

Vitamin B12 is essential for the formation and functioning of all cells. Its absence in the diet is most noticeable for its effects on red blood cells, and the condition is called pernicious anaemia. It is abundant in all animal-based foods, but people who eat a diet with no eggs or diary products (vegans) may develop signs of deficiency. However, deficiency is more likely to occur through a lack of intrinsic factor.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid)

This is a water-soluble vitamin and is essential for the maintenance of connective tissue. If it is lacking in the diet, bleeding will occur from the small blood vessels under the skin and mucous membranes, and if left untreated this will develop into scurvy, which can be fatal. Vitamin C is widely available in fruit and vegetables as well as in milk and liver. As a water-soluble vitamin it is easily lost when the vegetable is stored or in the cooking water.

Rich sources of vitamin C are fresh citrus fruits, black fruits such as blackcurrants, and green leaf vegetables.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that is found in oily fish, fish liver oils, animal liver, fortified margarines, butter milk and breakfast cereals. The form of vitamin D from these sources is known as cholecalciferol. Another source of vitamin D is through the action of ultraviolet B-rays in sunlight on 7-dihydrocholesterol found in the skin. This source of vitamin D may not be available for members of certain cultural groups (who for social, cultural or practical reasons are unable to expose themselves to enough sunlight) and also for individuals in long-term residential care. We need vitamin D to absorb calcium and phosphate from the intestine and this can be inhibited by some foods. Calcium and phosphorus are essential minerals that form healthy bones and teeth. Calcium is also an essential mineral for effective neuromuscular function as well as cell development.

Children who lack any of these nutrients tend to develop deformed long bones (rickets), adults develop osteomalacia, or bones that are principally made up of collagen and have a deficiency of the calcium and phosphorus that gives them their density and hardness. If there is a shortage of vitamin D, the body is unable to absorb calcium from the diet, and under the influence of parathyroid hormone it tries to maintain the level of calcium in the body by leaching existing calcium from the bones, causing osteoporosis. Adding calcium supplements to the diet of people with a predisposition to osteoporosis reduces bone loss and the risk of them developing fractures.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is a group of fat-soluble substances called tocopherols; they are widespread in the diet and deficiency is rare.

Vitamin K is a fat-soluble vitamin that is unusual in the diet, but deficiency is rare in otherwise healthy people as most people have bacteria in their large intestines that can manufacture vitamin K as a by-product, which is then absorbed and utilized in the body.

Micronutrients and the diet

One of the best ways to ensure that the required micronutrients are received is to eat plenty of fruit and vegetables. Studies consistently show that people who eat five or more portions of fruit and vegetables are healthier than those who do not (outlined in Vines 1996). The effect is quite strong, and not fully understood. Certainly fruit and vegetables tend to be rich in vitamins and minerals and low in fat, but high in fibre. However, there are probably other compounds that we are only just learning about that are present in fruit and vegetables and that are very beneficial to health.

It has been shown that quite limited intervention encouraging greater consumption of fruit and vegetables can have impressive outcomes in terms of blood cholesterol and other indicators of health (Steptoe et al 2003). The evidence is now so convincing that ‘five a day’ is government policy, and there are many initiatives designed to increase the intake of fruit and vegetables (Department of Health 1998). For instance, all schoolchildren between the ages of 4 and 6 years should receive one piece of fruit on each school day. Some people regard the ‘five a day’ target as unreasonably high. These people should have it explained to them about the wide range of foods that ‘count’ as fruit and vegetables; the food can be in any form, including tinned, frozen then cooked, dried or pureed. However, potatoes, in any form, do not count; they form a very useful part of the diet, but have a different role. People are often surprised to learn that tinned baked beans, dried fruit and fruit juices all contribute to a healthy diet.

Minerals

Minerals are also micronutrients that are required by the body in small quantities. Minerals are of inorganic origin (i.e. they are found in rocks and soil). Of course, unlike animals, humans do not normally lick rocks to obtain these nutrients; instead, they get them from water, or from plants and animals that have ingested them. One of the most important minerals in the body is iron, as it is essential for the formation of haemoglobin and thus the transport of oxygen around the body.

Calcium and magnesium are important for bone development and muscle contraction.

Table 8.4 lists some of the more important minerals, their sources in food and their action.

| Name | Source | Function | Deficiency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | Red meat, cereals and cereal products | Formation of haemoglobin | Anaemia | Deficiency is common in this country |

| Calcium | Milk, yoghurt, cheese | Healthy teeth and bones, muscle contraction | Rickets, osteomalacia, osteoporosis | Requires vitamin D for absorption and deposition |

| Zinc | Cheese, meat eggs | Wound healing, enzyme activity | Poor wound healing, ?depression | |

| Sodium in the form of sodium chloride (‘salt’) | Abundant, particularly in cooked/processed foods | Water balance, nerve and muscle function | Heat exhaustion | Most adults take too much, which may damage cardiovascular health |

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree