Understand the steps involved in doing a literature review

Identify bibliographic aids for retrieving nursing research reports and locate references for a research topic

Identify bibliographic aids for retrieving nursing research reports and locate references for a research topic

Understand the process of screening, abstracting, critiquing, and organizing research evidence

Understand the process of screening, abstracting, critiquing, and organizing research evidence

Evaluate the style, content, and organization of a literature review

Evaluate the style, content, and organization of a literature review

Define new terms in the chapter

Define new terms in the chapter

Key Terms

Bibliographic database

Bibliographic database

CINAHL

CINAHL

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

Keyword

Keyword

Literature review

Literature review

MEDLINE

MEDLINE

MeSH

MeSH

Primary source

Primary source

PubMed

PubMed

Secondary source

Secondary source

A literature review is a written summary of the state of evidence on a research problem. It is useful for consumers of nursing research to acquire skills for reading, critiquing, and preparing written evidence summaries.

BASIC ISSUES RELATING TO LITERATURE REVIEWS

Before discussing the activities involved in undertaking a research-based literature review, we briefly discuss some general issues. The first concerns the purposes of doing a literature review.

Purposes of Research Literature Reviews

The primary purpose of literature reviews is to summarize evidence on a topic—to sum up what is known and what is not known. Literature reviews are sometimes stand-alone reports intended to communicate the state of evidence to others, but reviews are also used to lay the foundation for new studies and to help researchers interpret their findings.

In qualitative research, opinions about literature reviews vary. Grounded theory researchers typically begin to collect data before examining the literature. As a theory takes shape, researchers turn to the literature, seeking to relate prior findings to the theory. Phenomenologists and ethnographers often undertake a literature search at the outset of a study.

Regardless of when they perform the review, researchers usually include a brief summary of relevant literature in their introductions. The literature review summarizes current evidence on a topic and illuminates the significance of the new study. Literature reviews are often intertwined with the problem statement as part of the argument for the study.

Types of Information to Seek for a Research Review

Findings from prior studies are the “data” for a research review. If you are preparing a literature review, you should rely mostly on primary sources, which are descriptions of studies written by the researchers who conducted them. Secondary source research documents are descriptions of studies prepared by someone else. Literature reviews are secondary sources. Recent reviews are a good place to start because they offer overviews and valuable bibliographies. If you are doing your own literature review, however, secondary sources should not be considered substitutes for primary sources because secondary sources are not adequately detailed and may not be completely objective.

| TIP For an evidence-based practice (EBP) project, a recent, high-quality systematic review may be sufficient to provide the needed information about the evidence base, although it is usually a good idea to search for studies published after the review. We provide more explicit guidance on searching for evidence for an EBP query in the chapter supplement on |

A literature search may yield nonresearch references, including opinion articles, case reports, and clinical anecdotes. Such materials may broaden understanding of a problem or demonstrate a need for research. These writings, however, may have limited utility in research reviews because they do not address the central question: What is the current state of evidence on this research problem?

Major Steps and Strategies in Doing a Literature Review

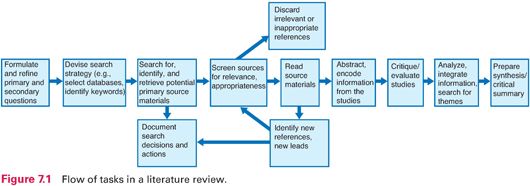

Conducting a literature review is a little bit like doing a study: A reviewer starts with a question and then must gather, analyze, and interpret the information. Figure 7.1 depicts the literature review process and shows that there are potential feedback loops, with opportunities to go back to earlier steps in search of more information.

Reviews should be unbiased, thorough, and up-to-date. Also, high-quality reviews are systematic. Decision rules for including a study should be explicit because a good review should be reproducible. This means that another diligent reviewer would be able to apply the same decision rules and come to similar conclusions about the state of evidence on the topic.

| TIP Locating all relevant information on a research question is like being a detective. The literature retrieval tools we discuss in this chapter are helpful, but there inevitably needs to be some digging for, and sifting of, the clues to evidence on a topic. Be prepared for sleuthing! |

Doing a literature review is in some ways similar to undertaking a qualitative study. It is useful to have a flexible approach to “data collection” and to think creatively about opportunities for new sources of information.

LOCATING RELEVANT LITERATURE FOR A RESEARCH REVIEW

An early step in a literature review is devising a strategy to locate relevant studies. The ability to locate evidence on a topic is an important skill that requires adaptability—rapid technological changes mean that new methods of searching the literature are introduced continuously. We urge you to consult with librarians or faculty at your institution for updated suggestions.

Developing a Search Strategy

Having good search skills is important. A particular productive approach is to search for evidence in bibliographic databases, which we discuss next. Reviewers also use the ancestry approach (“footnote chasing”), in which citations from relevant studies are used to track down earlier research on which the studies are based (the “ancestors”). A third strategy, the descendancy approach, involves finding a pivotal early study and searching forward to find more recent studies (“descendants”) that cited the key study.

| TIP You may be tempted to begin a literature search through an Internet search engine, such as Yahoo, Google, or Bing. Such a search is likely to yield a lot of “hits” on your topic but is unlikely to give you full bibliographic information on research literature on your topic. |

Decisions must also be made about limiting the search. For example, reviewers may constrain their search to reports written in one language. You may also want to limit your search to studies conducted within a certain time frame (e.g., within the past 10 years).

Searching Bibliographic Databases

Bibliographic databases are accessed by computer. Most databases can be accessed through user-friendly software with menu-driven systems and on-screen support so that minimal instruction is needed to retrieve articles. Your university or hospital library probably has subscriptions to these services.

Getting Started With an Electronic Search

Before searching a bibliographic database electronically, you should become familiar with the features of the software you are using to access it. The software has options for restricting or expanding your search, for combining two searches, for saving your search, and so on. Most programs have tutorials, and most also have Help buttons.

An early task in an electronic search is identifying keywords to launch the search (although an author search for prominent researchers in a field is also possible). A keyword is a word or phrase that captures key concepts in your question. For quantitative studies, the keywords are usually the independent or dependent variables (i.e., at a minimum, the “I” and “O” of the PICO components) and perhaps the population. For qualitative studies, the keywords are the central phenomenon and the population. If you use the question templates for asking clinical questions in Table 2.1, the words you enter in the blanks are likely to be good keywords.

| TIP If you want to identify all research reports on a topic, you need to be flexible and to think broadly about keywords. For example, if you are interested in anorexia, you might look up anorexia, eating disorders, and weight loss and perhaps appetite, eating behavior, food habits, bulimia, and body weight changes. |

There are various search approaches for a bibliographic search. All citations in a database have to be coded so they can be retrieved, and databases and programs use their own system of categorizing entries. The indexing systems have specific subject headings (subject codes).

You can undertake a subject search by entering a subject heading into the search field. You do not have to worry about knowing the subject codes because most software has mapping capabilities. Mapping is a feature that allows you to search for topics using your own keywords rather than the exact subject heading used in the database. The software translates (“maps”) your keywords into the most plausible subject heading and then retrieves citation records that have been coded with that subject heading.

When you enter a keyword into the search field, the program likely will launch both a subject search and a textword search. A textword search looks for your keyword in the text fields of the records, i.e., in the title and the abstract. Thus, if you searched for lung cancer in the MEDLINE database (which we describe in a subsequent section), the search would retrieve citations coded for the subject code of lung neoplasms (the MEDLINE subject heading used to code entries) and also any entries in which the phrase lung cancer appeared, even if it had not been coded for the lung neoplasm subject heading.

Some features of an electronic search are similar across databases. One feature is that you usually can use Boolean operators to expand or delimit a search. Three widely used Boolean operators are AND, OR, and NOT (in all caps). The operator AND delimits a search. If we searched for pain AND children, the software would retrieve only records that have both terms. The operator OR expands the search: pain OR children could be used in a search to retrieve records with either term. Finally, NOT narrows a search: pain NOT children would retrieve all records with pain that did not include the term children.

Wildcard and truncation symbols are other useful tools. A truncation symbol (often an asterisk, *) expands a search term to include all forms of a root. For example, a search for child* would instruct the computer to search for any word that begins with “child” such as children, childhood, or childrearing. In some databases, wildcard symbols (often ? or *) inserted in the middle of a search term permits a search for alternative spellings. For example, a search for behavio?r would retrieve records with either behavior or behaviour. For each database, it is important to learn what these special symbols are and how they work. Note that the use of special symbols, while useful, may turn off a software’s mapping feature.

One way to force a textword search is to use quotation marks around a phrase, which yields citations in which the exact phrase appears in text fields. In other words, lung cancer and “lung cancer” might yield different results. A thorough search strategy might entail doing a search with and without wildcard characters and with and without quotation marks.

Two especially useful electronic databases for nurses are CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and MEDLINE (Medical Literature On-Line), which we discuss in the next sections. We also briefly discuss Google Scholar. Other useful bibliographic databases for nurses include the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Knowledge, Scopus, and EMBASE (the Excerpta Medica database). The Web of Knowledge database is useful for a descendancy search strategy because of its strong citation indexes.

| TIP If your goal is to conduct a systematic review, you will need to establish an explicit formal plan about your search strategy and keywords, as discussed in Chapter 18. |

The CINAHL Database

CINAHL is an important electronic database for nurses. It covers references to hundreds of nursing and allied health journals as well as to books and dissertations. CINAHL contains about 3 million records.

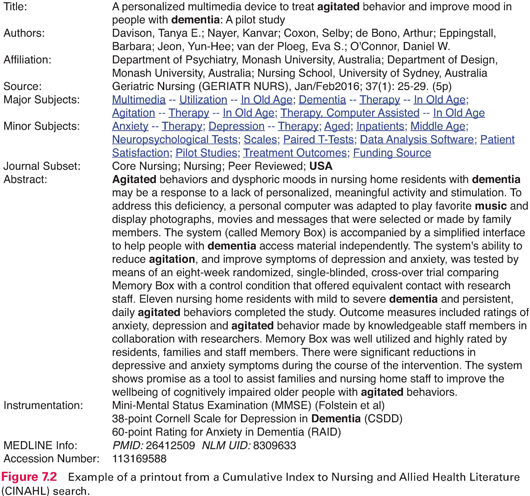

CINAHL provides information for locating references (i.e., the author, title, journal, year of publication, volume, and page numbers) and abstracts for most citations. Links to actual articles are often provided. We illustrate features of CINAHL but note that some features may be different at your institution and changes are introduced periodically.

A “basic search” in CINAHL involves entering keywords in the search field (more options for expanding and limiting the search are available in the “Advanced Search” mode). You can restrict your search to records with certain features (e.g., only ones with abstracts), to specific publication dates (e.g., only those after 2010), to those published in English, or to those coded as being in a certain subset (e.g., nursing). The basic search screen also allows you to expand the search by clicking the option “Apply related words.”

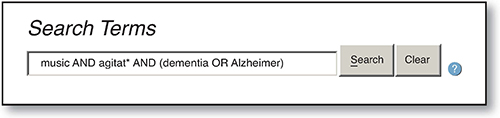

To illustrate with a concrete example, suppose we were interested in research on the effect of music on agitation in people with dementia. We entered the following terms in the search field and placed only one limit on the search—only records with abstracts:

By clicking the Search button, we got dozens of “hits” (citations). Note that we used two Boolean operators. The use of “AND” ensured that retrieved records had to include all three keywords, and the use of “OR” allowed either dementia or Alzheimer to be the third keyword. Also, we used a truncation symbol * in the second keyword. This instructed the computer to search for any word that begins with “agitat” such as agitated or agitation.

By clicking the Search button, all of the identified references would be displayed on the monitor, and we could view and print full information for ones that seemed promising. An example of an abridged CINAHL record entry for a report identified through this search is presented in Figure 7.2. The title of the article and author information is displayed, followed by source information. The source indicates the following:

Name of the journal (Geriatric Nursing)

Name of the journal (Geriatric Nursing)

Year and month of publication (Jan/Feb 2016)

Year and month of publication (Jan/Feb 2016)

Volume (37)

Volume (37)

Issue (1)

Issue (1)

Page numbers (25–29)

Page numbers (25–29)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree