Chapter 6. Family-centred care

Lynda Smith, Valerie Coleman and Maureen Bradshaw

LEARNING OUTCOMES

• Understand family-centred care as a concept in children’s nursing.

• Understand and appreciate the use of the practice continuum tool in children’s nursing practice.

• Use negotiation, empowerment and reflective skills in the delivery of family-centred care.

• Appreciate the challenges of delivering family-centred care in practice.

• Locate family-centred care within the wider context of inter-professional practice

• Understand the value of involving children and young people in decision making in the context of family-centred care

• Understand the professional and legal implications of using a family-centred approach to care.

Glossary

Concept

The way a particular subject is viewed and how it is classified. These views can vary from person to person, which is why family-centred care is difficult to define, because different individuals consider different aspects of family-centred care to be important.

Continuum

A continuum is a continuous whole rather than something that has a defined beginning and end. In this instance, continuum means that there is no start or finish point, that families can be on the continuum at any point and move along it in any direction.

Framework

Identifies and outlines the elements that explicitly belong to a subject, in this instance family-centred care. A number of frameworks describe the different elements or attributes of family-centred care.

Philosophy

An explicit statement of one’s beliefs and values. Family-centred care is an explicit statement about the values and beliefs of children’s nursing practice, in relation to the children and families in our care.

Self-efficacy

Individuals believe that ‘they are capable of performing a given activity’ (Tones & Tilford 2001 p 104). In terms of family-centred care, nurses can help families to develop self-efficacy beliefs by negotiating short-term goals related to the care of their children and by providing the appropriate support to enable the families to achieve. Achievement is likely to result in families believing that they are capable of performing this negotiated care and other aspects of their children’s care.

Introduction

Family-centred care is a multifaceted concept that has evolved over the past 60 years and remains a significant concept for children’s nursing in the 21st century. The concept embraces caring for the child in the context of the family and therefore nurses recognise the central role of the family in the child’s life.

Today’s healthcare culture, however, continues to present many challenges in translating family-centred care theory into practice, including inter-professional working and involving children and young people in making decisions in the context of family-centred care. The focus of this chapter is to clarify and enhance understanding of family-centred care as a theoretical construct and to discuss how this can be applied in everyday clinical practice using the practice continuum tool, which was developed for this purpose. This is supported by a toolkit of skills that will enable nurses to practice family-centred care effectively.

Understanding family-centred care as a concept

Different definitions and theoretical frameworks have been used to explain the evolving concept of family-centred care. These definitions and frameworks are all still reflected to some extent in the family-centred care approaches that are currently used by children’s nurses in practice. This is because some children’s nurses, using their professional judgement, will select the most appropriate family-centred care framework to meet the needs of individual children and their families. Conversely, other children’s nurses have not adopted contemporary theoretical family-centred care frameworks for implementation in practice and their approach to care is based on earlier theories. This may be due to choice or because of a lack of knowledge, skills or willingness to adopt new ways of working in practice. Bruce & Ritchie (1997) identify a need for skill development in areas of communication that involve negotiation and the sharing of information with children and their families. These areas of communication are defining characteristics of contemporary family-centred care theoretical frameworks. Bruce et al (2002) advocate the need for continuing education for healthcare professions working with families to further develop these communication skills.

This situation, concerning the use of different family-centred care frameworks in practice, can be confusing, making family-centred care potentially one of ‘nursing’s most amorphous concepts’ (Darbyshire 1994) and ‘rather ad hoc and unpredictable’ (Callery 1997). Dunst & Trivette (1996) argue that to improve family-centred care practice nurses need to understand the characteristics of using different approaches in their nursing care. Contemporary research/literature reviews have studied different aspects of the concept in an attempt to bring about this improvement, for example parental involvement (Ygge et al 2006); partnership (Lee 2007); negotiation (Corlett and Twycross, 2006 and McCann et al., 2008) and empowerment (Dampier 2002). Several of the examples in recent family-centred care studies use inter-professional examples (Law et al 2003) and others explore children’s involvement in decision-making (Coyne 2006) demonstrating the evolving nature of family-centred care.

Whilst the results of the MacKean et al (2005) study challenged the contemporary conceptualisation of family-centred care as ‘shifting care, care management and advocacy responsibilities to families’ (p 74) instead of collaborative working. It is therefore essential to have an awareness and understanding of functional, holistic, hierarchical and continuum family-centred care theoretical frameworks. Also Bruce et al (2002) and Franck & Callery (2004) recommend rethinking to develop a family-centred care research programme to study the application of family-centred care theory in practice as well as studying understanding of the philosophy (see evidence of recent attempts to evaluate family-centred care in practice, Lewis et al., 2007 and Murphy and Fealy, 2007).

Due to the evolving nature of the concept of family-centred care, different definitions have underpinned the development of these different theoretical frameworks.

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice• How are families involved in their children’s care on your clinical placement?

• Define family-centred care based on this reflection.

Your definition is likely to reflect one of the definitions provided by others to underpin the different family-centred care theoretical frameworks that exist. An early definition was:

Family-centred care provides an opportunity for the family to care for the hospitalised child under nursing supervision … The goal of family-centred care is to maintain or strengthen the roles and ties of the family with the hospitalised child in order to promote normality of the family unit

(Brunner & Suddarth 1986 p 66)

This definition suggests that the nurse supervises care and plays a rather passive role with the family and no active role with children. It identifies the opportunity for families to be involved in the care of the hospitalised child and seems to recognise the importance of addressing the psychological needs of the child with regard to promoting normality of the family unit. This definition was largely congruent with societal values and beliefs – and the care of sick children (which predominantly took place in the hospital setting) – up to the early 1980s. However, children are now cared for at home whenever possible and hence family-centred care is likely to have a different meaning, because the context of care has changed. An overarching contemporary definition of family-centred care is:

The professional support of the child and family through a process of involvement, participation and partnership underpinned by empowerment and negotiation

(Smith et al 2002 p 22)

This definition recognises that family-centred care is not an ad hoc approach to care but that it requires the nurse to make use of professional knowledge and skills to support the child and family, participating in care in both hospital and community settings. It offers different dimensions to family-centred care (involvement, participation and partnership), which are ‘each in their own way relevant and provide an opportunity for families to be involved in the care of their child, preferably to an extent of their own choosing through negotiation with nurses’ (Smith et al 2002 p 22). In other words, family-centred care does not have to be the same for every family and it may change for individual families at different times during a child’s healthcare journey. The implications of this are that it is acceptable for family-centred care to be either nurse-led or family-led, making it significantly different from the earlier definition offered by Brunner & Suddarth (1986), which relied on nursing supervision. The contemporary definition also suggests that an outcome of family-centred care is the empowerment of children and their families, demonstrating its congruence with contemporary health policy in the 21st century, which advocates for child and family empowerment (Department of Health, 1999, Department of Health, 2000, Department of Health, 2003 and Department of Health, 2004).

Other contemporary definitions include Shields et al (2006) which emphasises the need to plan care around the whole family and to recognise them as care recipients as well as carers. The Institute of Family Centered Care (2008) views family-centred care as an approach that is governed by mutually beneficial partnerships between healthcare providers, patients of all ages and families. Whilst this chapter refers to family-centred care there has been a change in policy (Department for Education and Skills, 2004a and Department of Health, 2004) and literature to child-centred care to conceptualise/define children as central to and as active participants in their own care.

www

www

Scenario

Scenario

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

Helen, a registered children’s nurse on part 1 of the nursing and midwifery council’s professional register, is Gemma’s mentor

www

wwwRead ‘Getting the right start: national service framework for children standard for hospital services’ (DoH 2003) online:

This emphasises the need to work in partnership with families and to involve them in decision making.

Scenario

ScenarioGemma, a second year student nurse, starts her clinical placement on a children’s medical ward. She is keen to learn about family-centred care and asks her mentor lots of questions.

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATIONHelen, a registered children’s nurse on part 1 of the nursing and midwifery council’s professional register, is Gemma’s mentor

Issues affecting the use of family-centred care theoretical frameworks for nursing practice on different children’s wards

I have been qualified for 3 years now. When I worked as a staff nurse on the children’s surgical ward we usually asked the families to continue to give ‘basic care’ to their children in hospital, just like they would at home. I don’t think they always wanted to do it but most families would comply, especially when they saw other families doing the care. We wanted them, for example, to feed their children, help with hygiene needs and to play with the children. The families were all treated the same with regard to involving them in caring for their children, except of course if the child was very ill and it was better for the nurse to do all the care then. Sometimes we had to teach the child or the family how to do some of the nursing or medical care to enable them to care for the child on discharge home. This all took time and some of my colleagues used to be rather impatient and judgemental with families who were slower to learn than others.

I started working on the medical ward about 3 months ago. Family-centred care is very different here, because we really do seem to give individual care to the different families. We listen to what the child and different family members have to say and information-giving is a two-way process. After all, the family are the experts on their child. The families still give ‘basic care’ to their children but we negotiate with them so that they can choose what care they want to participate in and when. We also assess their learning needs and teach them accordingly either to adapt their skills or to learn new ones. In fact, the children and families are much more involved altogether on this ward. The families really do participate in the decision-making process about their children’s care and many do work in partnership with us.

Helen is distinguishing between using a functional framework on the children’s surgical ward and using a holistic framework on the children’s medical ward.

In practice, using a functional framework results in a lack of collaboration between the nurse and family. In other words, families are understood in terms of having a functional value and they become resources to be effectively used and managed by nurses (Darbyshire 1993). The nurse using a functional framework takes on the role of gatekeeper and decides what care the family can participate in (Hutchfield 1999). Families are allowed to continue performing tasks that they would usually perform at home in hospital to help the nurse and to make them feel useful (Darbyshire, 1993 and Nethercott, 1993). Although some families might be involved in more technical aspects of the child’s care, that depends on their willingness and ability, as assessed by nurses (Nethercott 1993). The power very much resides with the nurse when this functional approach to family-centred care is used.

The holistic approach to family-centred care had its origins within the framework developed in 1987 by Shelton and colleagues, which identifies a framework of elements all linked together by a strong thread of communication (Shelton & Smith Stepanek 1995). It has a fundamentally different underlying philosophy to the functional approach (Smith et al 2002):

It is an approach that requires nurses to shift from a professionally centred view of health care to a collaborative model that recognises the family as central to a child’s life

(Ahmann 1994, p 113)

The holistic approach is grounded in respect for and cooperation with the family (Hutchfield 1999). It is underpinned by the principle that there should be an exchange of complete and unbiased information between the family and professionals (Shelton & Smith Stepanek 1995). The approach recognises that all families have some strengths. Nurses can help families to recognise these strengths and build on them to participate in the provision of optimum care to their own children. Families are more likely to take the lead in care and to work in partnership with nurses when this approach is used, as opposed to the nurse-led functional approach.

Hierarchical frameworks may also be used to underpin the practice of family-centred care. The evolvement of the concept of family-centred care has seen a move from parental involvement to parental participation through to partnership working and collaborative working, and finally to family-centred care. It could be that one concept has replaced the other during the evolvement of the concept of family-centred care, but Cahill (1996) suggests that there is a hierarchical relationship between the concepts. Hutchfield (1999) proposes that involvement, participation and partnerships are precursors and depicts them at the lower levels of a hierarchy that has family-centred care at the highest level. The differences between the levels of participation are clearly explained. Nurses, through accurate assessment and negotiation with children and families, are able to use the framework to identify the appropriate level of care for individual families and may then facilitate the family engaging in care at this level. Reassessment may result in families staying at the same level or moving up a level on the hierarchy (Darbyshire 1994).

Seminar discussion topic

Seminar discussion topic

Seminar discussion topic

Seminar discussion topicAdvantages and disadvantages of functional, holistic and hierarchical family-centred care theoretical frameworks

There are advantages and disadvantages of using all these theoretical frameworks.

The functional framework may be judged to be appropriate because families with a sick child will prefer nurses to lead the care and to be told what to do. However, families can be disempowered by this approach, in which the power remains with the nurse as the gatekeeper.

Holistic frameworks are positive because the family members are valued and respected as individuals. The family can negotiate its participation in care and is empowered to work in partnership with the nurse. Conversely, some families may feel they have too much responsibility in care and on occasions they could do ‘with a break’.

The hierarchical framework is really positive because ‘it recognises that families want to participate in the care of their children in hospital at a level of their own choosing’ (Smith et al 2002 p 29). Conversely, the hierarchical framework suggests that families move up the hierarchy and that there is not the option to return to a lower level of participation in care.

Another criticism of hierarchical frameworks is that nurses only use them to negotiate levels of care for families and not to find out about family experiences of living with a sick child in hospital (Darbyshire 1994).

To conclude, there are pros and cons to all these frameworks.

Family-centred care: the practice continuum tool

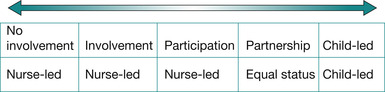

This tool has been developed specifically for use in clinical practice. On the continuum (Fig. 6.1), families are facilitated to move in either direction at any time according to individual family and nursing needs. The practice continuum tool can be used for the delivery of family-centred care in any clinical setting involving families both in hospital and in the community.

|

| Fig. 6.1 Family-centred care: the practice continuum tool (reproduced from Smith et al 2002 with permission of Palgrave Macmillan). |

The practice continuum tool acknowledges the key elements identified by the literature. Thus it comprises parental/child involvement, participation, partnership and parent/child-led care. ‘No involvement’ is also included to encompass the full spectrum of care that may be experienced by the child within the context of his or her family. The child/young person has been explicitly identified within the continuum to acknowledge the varying degrees in which they may be active participants in their care including planning, delivery and management.

The practice continuum tool was synthesised from available research and theoretical material, as well as practice experience, and therefore incorporates all the elements of the theoretical frameworks already discussed. Children’s nurses should be familiar with the terms contained within the tool but because these terms are sometimes used interchangeably to mean the same thing, and because using the practice continuum tool provides practitioners with a dialogue through which to articulate family-centred care in a meaningful and achievable way, it is important to understand what we mean by the following terms:

• Nurse-led care, no family involvement: this may occur in situations where the family is not able or willing to be involved for a particular reason for a period of time. This is still family-centred care because the nurse still uses a family-centred focus in care delivery in the family’s absence.

• Nurse-led care, family/child involvement in care: this may occur when the family is involved in some basic care, such as feeding, hygiene and/or emotional support. The nurse takes the lead in care management at this stage.

• Nurse-led, family/child participation in care: a good rapport is established, which is collaborative in nature, and the family participates in chosen aspects of nursing care following negotiation. The nurse continues to oversee care management and where necessary teaches relevant care skills to the child and/or family.

• Equal status, family/child partnership in care: this is exemplified by the change in the nurse’s role to becoming more of a supporter and facilitator. As families become more empowered they resume their role as primary care givers and the relationship with the nurse is much more equal in nature.

• Parent/child-led care, nurse-consulted care: the family is now expert in all aspects of the child’s care. There is a mutual, respectful relationship with the nurse, who is used in a consultative capacity from time to time. Although this is expressed explicitly as parent-led care, the implicit notion is that children are involved in their care and can lead their care in some instances.

No matter where the family is on the practice continuum, it is family-centred care; family-centred care is not only achieved by reaching an ‘end stage’. Parents negotiating with the nurse choose where they wish to be on the continuum. For some this may be a progression along the continuum, particularly for those families with a child with an ongoing illness, whereas others may prefer to be involved differently, providing normal childcare and emotional support only.

Research has consistently shown that parents want to be actively involved in their child’s care (Espezel & Canam 2003, MacKean et al 2005) and they want their involvement to be negotiated not assumed or expected (Kirk 2001, O’Haire & Blackford 2005). By communicating effectively with families, nurses can focus on their specific needs in relation to family-centred care rather than adopting a blanket approach to it (Smith et al 2002).

The strength of the practice continuum tool is its ability to respond to individual need day by day/shift by shift as the child and family’s situation changes. Hence nurses facilitate forward and backward movement along the practice continuum tool as the child’s condition changes or as family circumstances dictate. Ongoing evaluation is very much a part of the nurse’s caregiving role and therefore incorporating such an explicit approach to family-centred care should not be onerous and will facilitate communication between different nurses caring for the family.

PowerPoint

PowerPoint

PowerPoint

PowerPointAccess the companion PowerPoint presentation for guidelines on using the practice continuum tool.

Toolkit of skills

To be able to use the practice continuum tool, or any other theoretical family-centred care framework, children’s nurses need to have a toolkit of skills to empower families to negotiate their way through the interfaces of different healthcare environments. Good communication and teaching skills are essential for the successful implementation of family-centred care.

Communication skills

Without good communications skills, assumptions may well be made about what families will do for their children in hospital and in the community.

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice• Think of some examples of good practice in family-centred care that you have observed.

• What communication skills did the nurse use?

You probably mentioned skills like listening, explaining, clarifying, using open-ended questions and negotiating. Communication frameworks that enable skills like these to be used should be chosen to facilitate nurses and families working collaboratively together to care for children. The LEARN model framework (Berlin & Fowkes 1983) promotes interaction between the nurse and family, encouraging active listening by both parties, and acknowledges perceptual differences and similarities with regard to problems and negotiation about the child’s care. LEARN is an acronym:

L = Listen

E = Explain

A = Acknowledge

R = Recommend

N = Negotiate.

The Nursing Mutual Participation Model (Curley, cited in Ahmann 1994) requires asking open-ended questions to find out how the child and family feel that they can best participate in care. Families usually know their own child best and therefore professionals should not make independent decisions about involving them in care. Casey (1995) suggests that person-centred nurses are skilled practitioners who are willing to share their knowledge and expertise and to listen to families. Families may well become disempowered if decision making is taken out of their control and they are put in a position where they are expected to undertake aspects of their child’s care that they are not competent to do or are not happy about doing.

Empowerment

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice• Identify a situation in which either a family or yourself was disempowered.

• What were the inner and outer manifestations of this disempowerment?

Disempowerment engenders such feelings as being: out of control, confused, anxious, angry and frustrated over not being heard by healthcare professionals. These are obviously very strong negative feelings, which need to be avoided, and hence there is a need for collaborative working in family-centred care to empower families. Empowerment is a reciprocal social process that helps people to participate with competence (Coleman 1998) and to assert control over factors that affect their lives (Gibson 1991).

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

Helen, a registered children’s nurse on part 1 of the nursing and midwifery council’s professional register, discusses the empowerment of families with Gemma, a student nurse

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATIONHelen, a registered children’s nurse on part 1 of the nursing and midwifery council’s professional register, discusses the empowerment of families with Gemma, a student nurse

Issues affecting family empowerment on a children’s ward

It took me a long while to really understand what empowerment was all about. It wasn’t until I started working on this ward that it began to make sense. This was because we are encouraged to get to know the children and their families quite well (even those that are only in a short time) and really build up a trusting relationship with them. This makes it easier to negotiate with them and to agree on their participation in chosen aspects of their child’s care. Families also seem more receptive to our teaching and information giving because we have taken time to listen to them and to find out about them as a family unit. We also involve children as much as possible in their own care and decision-making, that does not always have to be about major issues, because it seems to help by enabling them to have some control over the situation. It’s really good when the families become competent in doing negotiated aspects of their child’s care. The families grow in confidence and then are usually ready to learn to do other aspects of the child’s basic or nursing care.

Helen is describing empowerment both as an outcome and a process.

Empowerment outcomes

Children and their families have to take some power and control over their own situation to be able to reach empowerment outcomes. This does not mean having power over others. Instead, it signals that a family has taken some of the power from health professionals so that it can make decisions itself about the child’s healthcare and/or give nursing care to the children. In their study of the families of children with middle ear infections, Wuest & Stern (1991) found that empowerment outcomes were domain specific. The families did not achieve an effective management of care outcome and stay there because new events in their child’s healthcare journey would result in them moving along the continuum to adopt more passive behaviours until further competencies were developed for empowerment in new domains. However, these families developed an increasing repertoire of management strategies, which they used in different domains of their child’s care to achieve empowerment outcomes. This suggests that an empowerment outcome increases family confidence and that it is also a regenerative process. Empowerment outcomes may be achieved in physical, social and/or psychological domains, or an outcome of empowerment may ‘simply’ mean that children and their families develop a sense of psychological well-being, promoting feelings of being in control of the situation in which they find themselves instead of being powerless or disempowered (Coleman 2002).

The empowerment process

The empowerment process is described as being a four-stage process (Gibson, 1995, Kieffer, 1984 and Tones and Tilford, 2001):

• Stage one: the entry stage is triggered by a specific incident, which leads to the discovery of the personal reality of the situation.

• Stage two: critical reflection to search for and identify the root cause of that reality to be able to move forward. Mentor and peer relationships are seen as being important during this stage.

• Stage three: this is a self-development stage, which may involve examining the implications of actions and may result in individuals wanting to ‘take charge’ of a situation.

• Stage four: this stage involves developing plans of action, gaining participatory competence in care, taking power from professionals and holding on to it.

During the four stages of the empowerment process a caring relationship should evolve between nurse and family, within which there is building of trust, connecting, mutual knowing and creating to promote self-esteem, self-confidence and self-insight (McWilliam et al 1997) to empower children and families.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access